Sample Reading Skills Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The question of reading skill includes definitional and substantive components. The definitional question is answered as follows: reading skill is an individual’s standing on some reading assessment. Skilled readers are those who score above some standard on this assessment; readers of low skill are those who score below some standard. The substantive question is this: What are the processes of reading that produce variation in assessed reading skill? This question is the focus here: given that two individuals differ in some global assessment of their reading, what differences in reading processes are candidates to explain this difference?

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Normal And Special Variation In Reading Skill

Is a single analysis of reading skill sufficient to characterize both ‘garden variety’ variation and severe reading difficulties? Severe difficulties in reading in the absence of general intellectual problems is the standard definition of dyslexia, or specific reading disability. The discrepancy between achievement in reading and achievement in other domains is what sets dyslexia apart. However, there are reasons to blur the distinction between specific and nonspecific reading problems. Individuals in the two categories may differ only in their achievements in some other nonreading area. The processes that go wrong in a specific disability may not be much different from those that go wrong for an individual who also has a problem in some other area (Stanovich and Siegel 1994). For both groups, difficulties in reading must be understood in terms of the processes of reading. What are the processes that can go wrong?

2. A Process Analysis

Reading processes depend on the language of the reader and the writing system that encodes that language. The units of the writing system are converted into mental representations that include the units of the language system. Specifically important are (a) the identification of words and (b) the engagement of language and general cognitive mechanisms that assemble these words into messages.

It is visual word identification that is the process most distinctive to reading. Beginning with a visual input—a string of letters—perceptual processes produce the activation of the grapheme units (individual and multiple letters) that constitute words. In traditional models of human cognition, the words are represented in a lexicon, the reader’s mental representation of word forms and meanings. Successful word reading occurs when there is a match between the input letter string and a word representation. As part of this process, phonological units, including individual phonemes associated with individual letters, are also activated. The joint contribution of graphemic and phonological units brings about the identification of a word. It is common to refer to the phonological contribution to this process as phonological mediation. It is also common to represent two pathways, one from graphemic units to meaning directly, and one from graphemic units to phonological units, and then to meaning (the mediation pathway). The issues of mediation and one-or-two routes are central to alternative theoretical models of the reading process.

The alternative models do not assume a representation system that stores words. In one class of nonrepresentational models, words emerge from patterns of parallel and distributed activation (Plaut et al. 1996). In resonance models, word identification results from the stabilization of dynamic patterns that are continuously modified by interactions among inputs and various dynamic states resulting from prior experience (Van Orden and Goldinger 1994). An interesting feature of this model is that patterns of graphic-phonological activation stabilize more rapidly than do patterns of graphic-semantic activation. In effect, a word form becomes identified primarily through the convergence of orthography and phonology. Meaning is slower to exert an influence on the identification process.

In considering reading skill, it is possible to ignore differences among theoretical models to a certain extent. However, the theoretical models of reading processes actually make some commitments about the sources of reading problems. For example, a dual route model allows two very different sources of word reading difficulties: Either the direct (print-to-meaning) route or the indirect (print-to-phonology-to-meaning) route can be impaired (Coltheart et al. 1993). This provides a model for both developmental and acquired dyslexia. In acquired dyslexia, surface dyslexics are assumed to have selective damage to the direct route; phonological dyslexics are assumed to have selective damage to the phonological route. For developmental dyslexia, children may have a phonological deficit or an ‘orthographic’ (direct route) deficit. However, single mechanism models with learning procedures can give an alternative account of developmental dyslexia: only one type, phonological dyslexia, is the result of a processing defect; surface or orthographic dyslexia becomes a delay in the acquisition of word-specific knowledge (Harm and Seidenberg 1999). Such an example illustrates that understanding individual differences in reading is part of the same problem as theoretical understanding of reading processes.

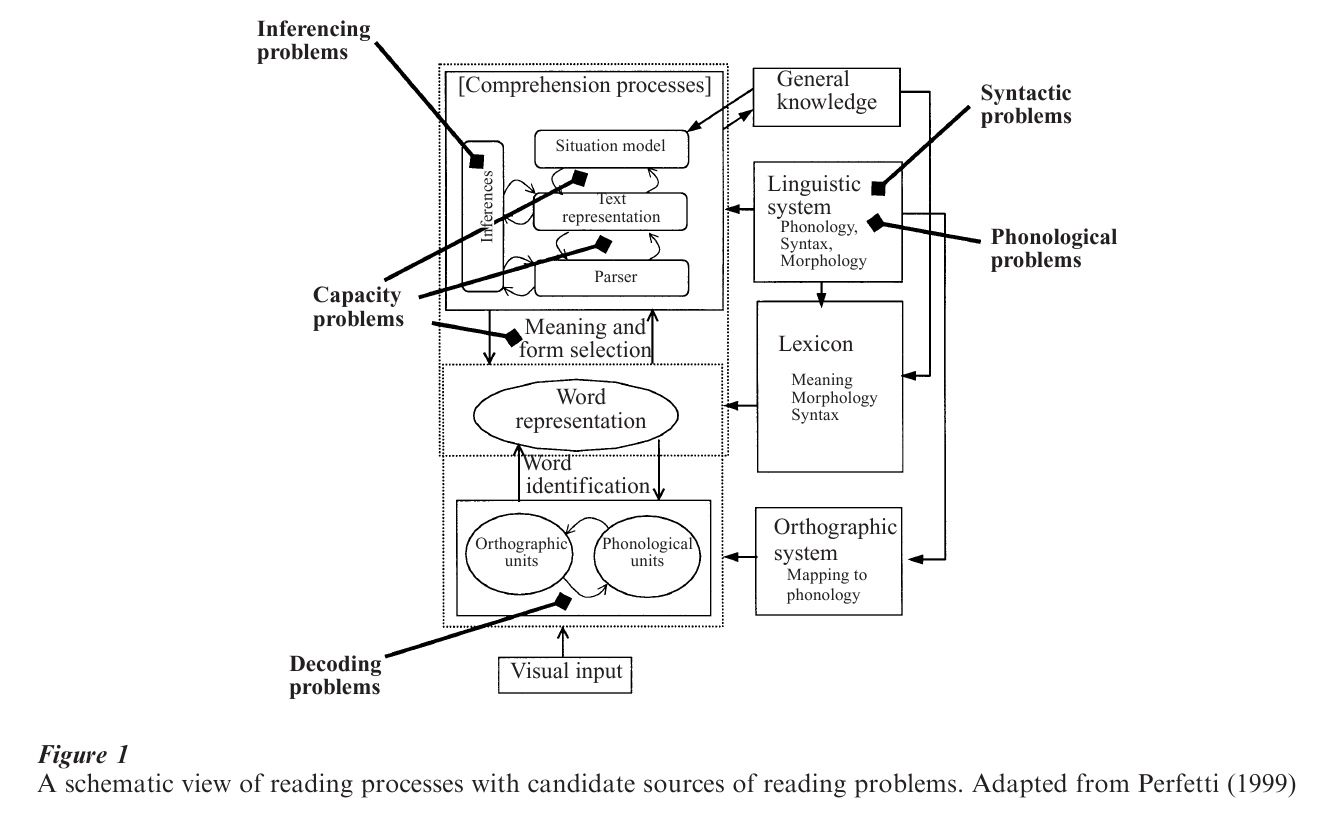

Figure 1 schematizes an organization of the cognitive architecture for reading. Reading begins with (a) a visual input that, with immediate use of phonology, leads to word identification that (b) yields semantic information connected to the word as constrained by the current context. A word immediately is (c) integrated syntactically with an ongoing sentence parse and (d) semantically with an ongoing message interpretation (proposition). As sentences are read (e), an integrated text representation is developed, consisting of interrelated propositions. To establish a reasonably specific understanding of a text, (f) inferences establish a coherent referential model of what is being read.

Potential reading difficulties are seen in each component. At the word level, a reader could have trouble with processing letter strings or in selecting the required meaning of a word. A reader might have defective phonological processes, limiting word identification and memory for words. On the comprehension end, a reader could have syntactic difficulties or fail to generate inferences or to monitor comprehension. Because these processes can demand mental resources from a limited pool, a very general constraint is working memory limitations. Thus reading difficulty can arise from a general limit in functional working memory capacity or from the failure of some processes to escape this limit. The following sections consider some of these possibilities.

2.1 Lexical Orthographic–Phonological Processes

Readers who fail to read words accurately fail to comprehend. Thus, word-level problems are potentially the most important in creating reading failures, because they lead both to word reading problems themselves and to derivative comprehension problems. For example, verbal efficiency theory (Perfetti 1985) assumes that readers who lack efficient word identification procedures are at risk for comprehension failure.

A word identification problem is a failure of phonological and/orthographic information to cohere onto a word identity (Fig. 1). Knowledge of letters and knowledge of phonemes that connect with letters in specific letter environments are necessary. Less skilled readers tend to have weaker knowledge of word spellings (orthography) and of word sounds (phonology), and especially weaker knowledge of orthography–phonology connections (decoding). Various measures assess phonological processes, but the ability to read legal non-words (pseudowords) has become a benchmark for decoding ability. Both the phonological and/orthographic components of word reading appear to have a significant heritable component (Olson et al. 1999).

The relationship between orthographic and phonological knowledge may be complex. As indicated in Fig. 1, an orthographic processing event is also a phonological processing event, perhaps implying that the two knowledge sources develop in tandem. However, the effects of reading experience may be a bit different for these two components. Early encounters with words may be crucial for establishing (phonological) decoding knowledge with orthographic knowledge acquired more gradually, as individual words are ‘practiced’ in reading situations. Stanovich and West (1989) found that reading experience accounts for variance in word reading skill beyond that accounted for by decoding. However, this does not mean that word knowledge gained through experience is independent of phonology. Indeed, early in reading experience, decoding unfamiliar words may be the primary mechanism for establishing orthographic representations of specific words (Share and Stanovich 1995). More generally, phonological processes that link graphic inputs to word identities may enable gains from further experience in reading, increasing the quality and quantity of word representations (Perfetti 1992).

Referring to ‘orthographic’ and ‘phonological’ as separate sources of knowledge does not entail a commitment to two separate routes in word identification. Whether as defects in the phonological component of single mechanism or as impairments of a distinct processing route, phonological problems may be the central deficiency for both specific reading disability and nonspecific low reading skill (Stanovich 1988). They can arise at many levels, including speech processing mechanisms and sensitivity to phonological structures, as well as written word identification. Becoming aware that spoken words consist of meaningless sound segments (phonemes) is important in learning to read, and children who do not become aware are at risk for failure (see Liberman and Shankweiler 1991). Moreover, phonological processing problems may have consequences throughout the reading process: learning to read words, remembering just-read words, and understanding phrases and sentences are all processes operating on partly phonological representations.

2.2 Processing Lexical Meaning

The ability to get context-appropriate meaning from words is central to reading skill. At one level, this is a question of vocabulary. The more words a reader knows, the better the comprehension. At another level, it is the ability to select the right meaning of a word in a given context. Although the description of lexical meaning selection has become complex, a still widely (not universally) shared conclusion is this: the selection of word meaning proceeds in two-stages: (a) a general activation stage in which a word is accessed and its associated meanings nonselectively activated, and (b) a selection stage in which the meaning appropriate for context is selected while meanings inappropriate for context are suppressed.

One hypothesis is that less skilled readers are less effective in selecting a contextually appropriate meaning. According to the structure building framework (Gernsbacher 1990), readers build a coherent framework for a text by enhancing concepts required by the text while suppressing those that are irrelevant. The suppression hypothesis is that less skilled readers have deficient suppression mechanisms. To illustrate, in the sentence, ‘He dug with the spade,’ the final word has two meanings, but only one fits the context of the sentence. However, when adult readers are immediately asked to decide whether a following word is related to the meaning of the sentence, their decisions are initially slow for the word ‘ace’ (related to the inappropriate meaning of spade). Both appropriate and inappropriate meanings may be activated at first. With more time before the appearance of ‘ace,’ skilled readers show no delay in rejecting it; i.e., they ‘suppress’ the irrelevant meaning. However, less skilled readers continue to react slowly to ‘ace,’ as if they have not completely suppressed the irrelevant meaning of ‘spade.’

Whether ineffective use of context is a source of reading problems has become a complex issue. Prescientific beliefs on this question seemed to be that poor readers failed to use context in reading words. However, research on children’s word identification led to the opposite result: less skilled readers use context in word identification at least as much and perhaps more than do skilled readers (Perfetti 1985, Stanovich 1980). Less skilled comprehenders are good users of context, which they use in compensation for weaker word identification skill to identify words. The suppression proposal adds to the poor reader’s basic word identification problem a specific suppression problem, the effect of which is a less productive use of context.

2.3 Processing Syntax

Less skilled readers often show a wide range of problems in syntax and morphology. The question is whether such problems, which are found across a wide age range, arise from some deficit in processing syntax or from some other source that affects performance on syntactic tasks. One possibility is that syntactic problems reflect a lag in the development of linguistic structures. An alternative hypothesis is that the syntactic problems reflect constraints of working memory or lexical processing limitations.

To illustrate one class of syntactic problem, consider two sentences with relative clauses below. (a) is the easier subject relative; (b) is the more difficult object relative.

(a) The girl that the boy believed understood the problem.

(b) The girl that believed the boy understood the problem.

The greater difficulty of (b) compared with (a) can arise from different degrees of interference they produce in the attempt to assigning a subject for ‘understood.’ For syntactic reasons, the interference produced by the object relative (b) is greater than the interference produced by the subject relative (a). Details aside, if syntactic deficits rest on lack of specific syntactic knowledge, then one might expect some qualitative differences between skilled and less skilled readers. However, in the relative clause example and in other syntactic examples, patterns of difficulty for skilled and less skilled young readers tend to be the same, suggesting quantitative rather than qualitative differences (Crain and Shankweiler 1988).

Research with adults suggests that both reading problems and spoken language problems (aphasia) may arise from processing limitations rather than structural deficits (Carpenter et al. 1994). In a study of subject and object relatives similar to those in (a) and (b), King and Just (1991) found that readers with low working memory have problems with object-relative sentences. More interesting, these problems (as seen in reading times for words) were most severe where the processing load was hypothesized to be the greatest— at the second verb in the object relative, i.e., ‘understood’ in (b). Comprehension difficulties may be localized at points of high processing demands— whether from syntax or something else. If this analysis is correct, then the problem is not intrinsic deficits in syntax, but the processing capacity to handle complexity.

Another perspective on this issue is the opportunity for practice. Because some syntactic structures are more typical of written language than spoken language, the opportunity for practice is limited by the ability to read. Thus, continuing development of reading skill as a result of initial success at reading— and the parallel increasing failure as a result of initial failure—is undoubtedly a major contributor to individual differences in reading.

2.4 Processing Text

The source of skill differences in text comprehension can lie in the lexical and working memory processes considered above or in higher-level processes specific to reading texts. In addition to identifying words, parsing sentences, and encoding context-sensitive meanings, readers must use knowledge from outside of the text and apply procedures that derive intended meanings. The overall complexity of text comprehension implies several possibilities for processing failure, any resulting in a less integrated or less coherent representation of the text.

One example is the processes of coreference, by which a reader maps a pronoun to an already established referent, as illustrated in (c).

(c) Jane saw Margaret shopping in the grocery store. She was buying bread.

When there are two possible referents for a pronoun, less skilled readers may take longer to assign the pronoun to the intended referent (Margaret in this case), at least when the referent is not the first noun in the preceding sentence (Frederiksen 1981). If this simple pronoun case is general, less skilled readers may be less adept at integrating referential information across sentences.

The text processing component that has received the most attention as a source of individual differences is making inferences. Oakhill and Garnham (1988) summarize evidence suggesting that less skilled readers fail to make a range inferences in comprehension. When skill differences are observed, an important question is whether they occur in the absence of problems in lexical skills, working memory, or other lower-level factors. The answer to this question remains unclear in much of the research. However, there has been some success in identifying a group of children whose problems can be considered comprehension-specific, although highly general across reading and spoken language (Stothard and Hulme 1996).

Another example is comprehension monitoring, the reader’s implicit attempts to assure a consistent and meaningful understanding. Skilled readers can use the detection of a comprehension breakdown (e.g., an apparent inconsistency) as a signal for rereading and repair. Less skilled readers may fail to engage this monitoring process (Baker 1984, Garner 1980). Low skilled comprehenders seem especially poor at detecting higher level text inconsistencies that negate a coherent model of the text content—for example, whether successive paragraphs are on unrelated topics. However, it is not clear whether these higher level differences are independent of the reader’s ability to construct a simple understanding of the text. Some evidence suggests that less skilled comprehenders fail accurately to represent or weight the propositions in a text (Otero and Kintsch 1992). The general interpretive problem here is that comprehension monitoring, like inference making, both contributes to and results from reader’s text representation. This makes it difficult to attribute comprehension problems uniquely to failures to monitor comprehension, as opposed to more basic comprehension failures.

Because no texts are fully explicit, the reader must import knowledge from outside the text. Thus, a powerful source of comprehension differences is the extent to which a reader has such knowledge for a given text (Anderson et al. 1977). However, readers of high skill can compensate for lack of knowledge to some extent (Adams et al. 1995). It is the reader who lacks both knowledge and reading skill who is assured failure. The deleterious effect of low reading skill (and its motivational consequences) on learning through reading creates readers who lack knowledge of all sorts.

3. Summary

With a focus on the component processes, individual differences in reading skill become a matter of understanding how these processes and their interactions contribute to successful reading outcomes. Where the successful outcome is reading individual words, the processes are localized in knowledge of word forms— both general and word-specific phonological and/orthographic knowledge—and word meanings. Inadequate knowledge of word forms is the central obstacle to acquiring high levels of skill. Severe problems in word reading reflect severe problems in phonological knowledge. Where the successful outcome is comprehension, the critical processes continue to include word processes, and problems in comprehension are associated with problems in word processing. In addition, processes that contribute to basic sentence understanding and sentence integration become critical. Processes that provide basic propositional meaning, including word meaning selection and parsing, and those that establish coherent text representations (integration processes, inferences, monitoring, conceptual knowledge) become critical to success. Less skilled readers, as assessed by comprehension tests, often show difficulties in one or more of these processes. Less clear is how to understand the causes of observed failures. A processing model helps to see the relationships among component processes and to guide studies of skill differences. The candidate causes of skill variation cannot be equally probable, when the output of lower-level processes are needed by higher level processes. The identification of basic causes, as opposed to derivative symptoms that reflect the costs of low reading skill, requires research that can provide strong causal tests.

Bibliography:

- Adams B C, Bell L C, Perfetti C A 1995 A trading relationship between reading skill and domain knowledge in children’s text comprehension. Discourse Processes 20: 807–23

- Anderson R C, Reynolds R E, Shallert D L, Goetz E T 1977 Frameworks for comprehending discourse. American Educational Research Journal 4: 367–81

- Baker L 1984 Spontaneous versus instructed use of multiple standards for evaluating comprehension: Effects of age, reading proficiency and type of standard. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 38: 289–311

- Carpenter P A, Miyake A, Just M A 1994 Working memory constraints in comprehension: Evidence from individual differences, aphasia, and aging. In: Gernsbacher M A (ed.) Handbook of Psycholinguistics. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 1075–122

- Coltheart M, Curtis B, Atkins P, Haller M 1993 Models of reading aloud: Dualroute and parallel-distributed-processing approaches. Psychological Review 100: 589–608

- Crain S, Shankweiler D 1988 Syntactic complexity and reading acquisition. In: Davison A, Green G M (eds.) Linguistic Complexity and Text Comprehension: Readability Issues Reconsidered. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 167–92

- Frederiksen J R 1981 Sources of process interactions in reading. In: Lesgold A M, Perfetti C A (eds.) Interactive Processes in Reading. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 361–86

- Garner R 1980 Monitoring of understanding: An investigation of good and poor readers’ awareness of induced miscomprehension of text. Journal of Reading Behaviour 12: 55–63

- Gernsbacher M A 1990 Language Comprehension as Structure Building. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

- Harm M W, Seidenberg M S 1999 Phonology, reading and dyslexia: Insights from connectionist models. Psychological Review 106: 491–528

- King J, Just M A 1991 Individual differences in syntactic processing. Journal of Memory and Language 30: 580–602

- Liberman I Y, Shankweiler D 1991 Phonology and beginning reading: A tutorial. In: Rieben L, Perfetti C A (eds.) Learning to Read: Basic Research and its Implications. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 3–17

- Oakhill J, Garnham A 1988 Becoming a Skilled Reader. Blackwell, New York

- Olson R K, Forsberg H, Gayan J, Defries J C 1999 A behavioral genetic analysis of reading disabilities and component processes. In: Klein R M, McMullen P A (eds.) Converging Methods for Understanding Dyslexia. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 133–53

- Otero J, Kintsch W 1992 Failures to detect contradictions in a text: What readers believe versus what they read. Psychological Science 3(4): 229–35

- Perfetti C A 1985 Reading Ability. Oxford University Press, New York

- Perfetti C A 1992 The representation problem in reading acquisition. In: Gough P B, Ehri L C, Treiman R (eds.) Reading Acquisition. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 145–74

- Perfetti C A 1999 Comprehending written language. A blue print of the Re. In: Hagoort P, Brown C (eds.) Neurocognition of Language Processing. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 167–208

- Plaut D C, McClelland J L, Seidenberg M S, Patterson K 1996 Understanding normal and impaired word reading: Computational principles in quasi-regular domains. Psychological Review 103: 56–115

- Share D L, Stanovich K E 1995 Cognitive processes in early reading development: Accommodating individual differences into a model of acquisition. Issues in Education 1: 1–57

- Stanovich K E 1980 Toward an interactive-compensatory model of individual differences in the development of reading fluency. Reading Research Quarterly 16: 32–71

- Stanovich K E 1988 Explaining the differences between the dyslexic and the garden-variety poor reader: The phonologicalcare variable-difference model. Journal of Learning Disabilities 21: 590–604

- Stanovich K E, Siegel L S 1994 Phenotypic performance profile of children with reading disabilities: A regression-based test of the phonological-core variable-difference model. Journal of Educational Psychology 86(1): 24–53

- Stanovich K E, West R F 1989 Exposure to pring and orthographic processing. Reading Research Quarterly 24: 402–33

- Stothard S, Hulme C 1996 A comparison of reading comprehension and decoding difficulties in children. In: Cornoldi C, Oakhill J (eds.) Reading Comprehension Difficulties: Processes and Intervention. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 93–112

- Van Orden G C, Goldinger S D 1994 The interdependence of form and function in cognitive systems explains perception of printed words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 20: 1269–1291.