Sample Education And Income Distribution Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

It is widely believed that income is differentiated by education, although the degree of the difference varies from country to country, from industry to industry, from occupation to occupation, and from individual to individual. Education contributes to raising an individual’s productivity and thus to increasing his or her earnings capacity provided that workers’ wages are paid according to their productivity. This is called the marginal productivity theory in economics.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

We can point out five reasons why an individual productivity is raised by education:

(a) Individuals not only acquire skills through formal education but also through job training. The human capital theory is common in this approach where an individual skill in production process and thus earning capacity requires formal (i.e., schooling) and informal training.

(b) Why does formal schooling raise productivity? The answer is that it imparts fundamental skills and technologies such as reading, writing, mathematical calculation, physics, chemistry, engineering, etc.

(c) Educated people can use other resources skillfully such as machines and new technologies. Also, they can decide quickly whether these resources and information are useful in raising productivity or lowering cost.

(d ) Education or schooling can socialize people into functioning effectively in society and economy. For example, schooling teaches people to be motivated, to be cooperative and patient, and to take roles in leadership, etc. This idea does not explain the increase in productivity through skill acquisition or knowledge of technique, but emphasizes mental and social aspects, which are likely to raise a group’s productivity. In other words, it is useful in modern society where a team production is common, and concerned with an organizational explanation.

(e) The human capital theory emphasizes the importance of both formal schooling and training in the production process. The concept of trainability suggests that an individual who received formal schooling is ready to receive training because he or she can learn from training quickly, and adopt it efficiently in the production process. At the same time, it is likely that a company can provide educated employees with training at cheaper cost because of the above properties.

Education certainly contributes to higher productivity. However, empirical findings regarding points (a)–(e) are mixed. This is, in particular, true when we contrast between the developing countries and the developed countries. The difference in farmers’ productivity in the developing countries can be verified by the degree of literacy rate and/or the enrolment rate in primary or secondary schools. However, nonagricultural jobs in the developed countries do not support the positive correlation between education and productivity. The reason is that more formal education raises the possibility that educated people may take jobs where productivity is higher. In other words, it is not easy to identify whether higher productivity in certain nonagricultural jobs can be explained by their higher educational attainment or that educated people take jobs where productivity is already higher.

There are similar problems in the relationship between education and income. Although it is true that education certainly raises an individual’s earning capacity, its empirical verifications are very mixed. At the same time, it is possible that some reasons other than the fact that education raises earning capacity may be responsible for the positive correlation between education and income. The present entry reviews these two issues fairly extensively, namely empirical effects of education on income, and possible other causes to explain the positive correlation be- tween education and income.

Before proceeding to these issues, it is necessary to make a distinction between income and earning. Income consists of earnings (labor incomes) and non- labor incomes such as interests, rents, pensions, etc. ‘Earnings’ is a better terminology when we are concerned with the effect of education on income because earnings are direct rewards for working activities. However, since income is used throughout this research paper note that here income normally implies (labor) earning.

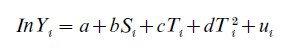

The human capital income function is the most popular form of empirical studies, which was developed by Mincer (1974), and its form was applied to many countries. The fundamental form of the Mincer type of human capital function (i.e., log earnings of individual (i ) is written as follows:

where Yi is annual income, Si is years of formal education, Ti is the number of years an individual has worked since the end of formal schooling, and ui is an error term. T represents potential labor market experience, which is supposed to indicate the influence of job training and of work experience. The reason why the squared form of T is introduced is that the influence of job training and of work experience has a quadratic form.

Empirical estimations based on this formula or its variations have been fairly successful in many countries. The implications and interpretations of this formula may be proposed in the following ways. First, if the estimated coefficient of b were positive with statistical significance, it would imply that the effect of education on income is positive. At the same time, the estimated magnitude of b would indicate the rate of return to education. Based on many empirical studies it is known that the estimated coefficient of b is positive and statistically significant, and thus that education certainly raises an individual earning capacity. The estimated rates of return to education are therefore different between countries, industries, and educational levels. Thus, it is risky to provide any conclusions about them. It is, nevertheless, possible to proclaim that they would be ranged between 0.05 and 0.25.

Second, the estimated R2 , which shows the degree of fit in statistical estimations based on this formula, indicates the degree to which the model is successful in estimating the variance of income. More concretely, it shows the degree to which education is able to explain the income inequality (i.e., variation of income). A large number of empirical studies suggest that about 10–40 percent of the variation in observed incomes can be explained by the model with a linear schooling term and a squared form in labor market experience.

Third, the relative importance of the schooling term and of the labor market experience term is different between countries, industries, occupations, etc. In other words, the influence of formal education is stronger than that of experience in one country, one industry, or one occupation in the determination of income, while the latter is stronger than the former in another country, another industry, or another occupation. It is nearly impossible to obtain a general feature about the relative importance of formal schooling versus labor market experience in the determination of income. It is difficult to determine which variable is more important to raise an individual earning capacity between formal schooling versus job training (or learning by doing).

There have been several serious modifications or alternative ideas for the original Becker (1964) formulation of education and the Mincer-type human capital earnings function both theoretically and empirically. Some of them are explained here.

First, one modification was presented by Card (1995) who extended the idea of Becker. Becker (1964) originally considered a model in which an individual finishes his or her formal schooling before entering the labor market. In reality, an individual goes back to formal schooling either full-time or part-time after entering the labor market, and then goes back to work after completely their education. In other words, an individual moves back and forth between full-time or part-time schooling and part-time or full-time work.

Card (1995, 1999) developed a model, which incorporates the movements of an individual in and out of the labor force. Concretely, Card was concerned with individual heterogeneity in optimal schooling choice. There are two sources which affect an individual choice, namely (a) differences in the costs of (or taste for) schooling and (b) differences in the economic benefits of schooling.

In addition, there is an issue of a specification bias in the effect of education on income. More concretely, ability (innate ability) of an individual may affect the determination of income, and an exclusion of ability from an earnings function is likely to provide a biased estimation of the effect of education on earnings.

A more formal analysis gives the following result. Ignoring other variables, a simple earnings function can be written,

![]()

where Y is income, S is education, and A is a measure of ability. When we ignore ability, we obtain a biased estimator of β as follows,

![]()

where the return to education is estimated with a bias. Thus, it is necessary to include A when ability has an independent positive effect on earnings, and the relationship between the excluded ability and included schooling variable is positive.

The classical study by Griliches (1977) concluded that the ability bias caused by the excluded ability was minor. There is a consensus not only based on the study by Griliches’ but also the subsequent studies that the exclusion of ability is not a serious problem. However, there remain several technical problems regarding the effect of ability on earnings. First, even if a popular variable such as IQ is included, there is a question about whether this indicates a proper measure of ability: a professional baseball player or a professional singer who receives a very high income does not necessarily do so because of a high IQ. Second, even if we assume that IQ is a relevant measure, it includes considerable measurement errors.

Another variable, which attracted many researchers in this field, is family background. It is observed that children’s schooling achievements are highly correlated with the characteristics of their parents’ status such as father’s education, mother’s education, parents’ income, etc. This is called intergenerational transfer of family status, and some specialists such as Bowles and Gintus (1976) proposed that the effect of education on income must be understood. The positive correlation between education and income is superficial because the effect of family background on income is more intrinsic than that of education in the presence of the predetermined effect of family background on children’s education.

A recursive type of an econometric model, which explains the causal relationships from family background to children’s education, and from children’s education to income, is capable of verifying this property. Griliches and Mason (1972) for the USA, Tachibanaki (1980) for France, Tachibanaki (1996) for Japan and Tachibanaki (1997) for the UK empirically support that the causal chain from family background to children’s education and income is valid in the developed countries.

Econometricians and statisticians are enthusiastic about various estimation methods to identify the true effect of individual ability, family background, and measurement errors in income and educational attainment. They often use sibling and twin-data, offspring data, etc. In order to consolidate the analysis it is necessary to apply more sophisticated estimation methods to these data. Since their methods and techniques are beyond the scope of this research paper, they are not described here (see Solon 1999, Card 1999).

Bibliography:

- Becker G S 1964 Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education. Columbia University Press, Columbia, NY

- Bowles S, Gintus H 1976 Schooling in Capitalist America. Basic Books, New York

- Card D 1995 Earnings, schooling and ability revisited. In: Polachek S (ed.) Research in Labor Economics. JAI Press, Stanford, CT, Vol. 14, pp. 23–48

- Card D 1999 The causal effect of education on earnings. In: Ashenfelter O C, Card D (eds.) Handbook of Labor Economics. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, Vol. 3A, pp. 1801–64

- Griliches Z 1977 Estimating the returns to schooling: Some econometric problems. Econometrica 45: 1–22

- Griliches Z, Mason W 1972 Education, income and ability. Journal of Political Economy 82: 74–103

- Mincer J 1974 Schooling, Experience and Earnings. NBER Columbia University Press, New York

- Solon G 1999 Intergenerational mobility in the labor market. In: Ashenfelter O C, Card D (eds.) Handbook of Labor Economics. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, Vol. 3A, pp. 1761–800

- Tachibanaki T 1980 Education, occupation and earnings: A recursive approach for France. European Economic Review 13: 103–22

- Tachibanaki T 1996 Wage Determination and Distribution in Japan. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Tachibanaki T 1997 United Kingdom. In: Tachibanaki T (ed.) Wage Differentials: An International Comparison. Macmillan Press, London, pp. 210–38