Sample Educational Systems in Asia Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, check out our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments at reasonable rates.

Asia is a vast continent with a large population. It accommodates a vast number of countries with diverse cultures and religions, at different states of economic development and with different political systems. Education, being a human activity, therefore also demonstrates a spectrum of varieties in Asia. Nonetheless, there are certain detectable trends in education development in the region, given strong trends of globalization and increased interactions between nations and cultures.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

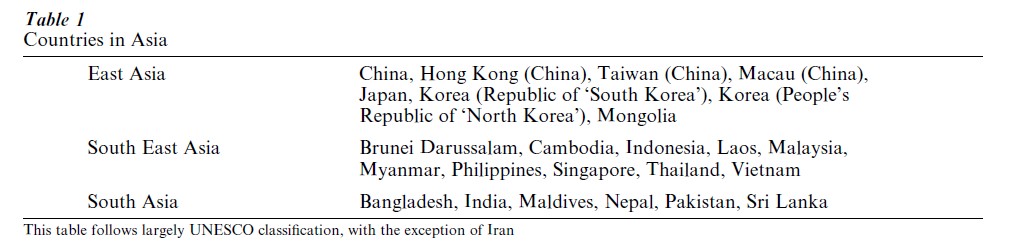

This research paper refers to subregions which are often known as East Asia, South East Asia and South Asia (see Table 1). It does not include three other major groups of nations: systems that belong to the former Soviet Union, systems in the Middle East, and the Pacific Islands.

In most of these nations/regions, there have been dramatic developments in basic education in the last two decades of the twentieth century, approaching universal basic education (which is defined differently in different systems) with varied degrees of accomplishment amidst various difficulties. There were also deliberate developments of vocational education in the past two decades, but it faces varied degrees of challenges given the change in the economy and the labor market. Higher education is relatively underdeveloped except in some of the most developed economies.

1. The Structures

The education systems in Asia are very much influenced by the West. The earlier systems of education, even in noncolonial China, and Japan, were modeled after the old German system and later the US system. The 6+3+3 system of primary, junior secondary and senior secondary schools has become the common pattern in Mainland China, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea in East Asia.

With the exception of Japan and Thailand, most of the nations and regions in Asia experienced colonial rule, and that has significance in the structure of the education systems. Quite a few systems in Asia adopt a traditional British model that took shape during colonial times. Hong Kong, Britain’s last colony in Asia until 1997, preserves a 6+3+2+2 system, with a three-stage secondary schooling: two years junior secondary, two-year senior secondary, leading to O-Level (Ordinary Level) examinations, and an additional 2 years of pre-university A-level (Advanced Level) study. Singapore maintains a similar system, except that there are staggered years of secondary schooling according to students’ abilities. The British model is still the norm in past British colonies such as Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Maldives, and Nepal. India, which was the largest British colony, maintains the same pattern, except that it has an integrated eight years’ basic education instead of nine.

Meanwhile, there are still traces of French influence in Vietnamese, Lao, and Cambodian education; these regions belonged to French Indochina. Likewise, Indonesia used to be a Dutch colony, and maintains a system that is more or less in line with the Dutch system. The Philippines were earlier colonized by Spain, and later mandated by the USA. They follow a very American system. Macao, a former Portuguese colony, has a blend of schools following the Portuguese and Chinese systems, respectively. In Mongolia and North Korea, the former Soviet model was followed.

2. The Cultures

Asia hosts a number of strong cultures. The strongest among them are the East Asian culture, the Indian culture, and the Moslem culture.

The East Asian culture, often also called the Confucian culture, prevails in communities that use chopsticks: the Chinese communities (the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macao), Japan, the two Koreas, Vietnam, and a large part of Singapore. Although there are significant variations between, and even within, these societies, they are often seen as societies of collectivism and conformity. They are cultures in which education inherits the strong examination orientation in ancient China, where formal education was the only path for upward social mobility. Societies in East Asia still place high values on formal education. These societies therefore often enjoy a high attendance rate, and are champions in international comparisons of educational achievements, particularly in the realms of science and mathematics. However, the examination orientation has also rendered the systems rather weak in the relevance of the curriculum and flexibility in learning. Among others, the East Asian education systems also place serious emphasis on the social or moral aspects of students’ development.

The Indian culture is an oversimplified umbrella term that covers different traditions derived from Hinduism. Against common beliefs, the South Asian subcontinent societies encompass a large variety of religions, including Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam. However, it is safe to say that Hinduism underpins a large part of the education philosophy in South Asia. The education systems in South Asia often carry a strong religious orientation, and emphasize the relations between humans and nature. Because of the British colonial past, many of the South Asian systems of education also bear a strong framework borrowed from the traditional British system.

There is a strong tradition of Islamic culture in some of the South East Asian nations: Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei Darussalam. There are also sizeable Islamic communities in China, India, and Singapore. The Moslems in Asia seem to have developed a particular paradigm about education, which is able to integrate the emphasis on human–God relations in traditional Islamic education, with the learning of science and modern technology within the education system.

The cultural factor plays an important part in the shaping of education systems in Asian nations. Overall, there is an emphasis on the social (human–human) and religious (human–God) dimensions in the educational philosophy, and separation of such from knowledge and skills. Hence, in most of the education systems in Asia, there have been comprehensive and deep-rooted traditions of education about morality, attitudes, and values.

The strong cultural traditions in Asia have influenced not only education within the respective nations regions, but have also affected the education of the Diaspora communities. The Chinese and Indian immigrants in other countries, for example, regardless of their countries of origin, are known for the outstanding academic performance of their children.

3. The Economy And Education

The continent also comprises nations in rather polar economic conditions. On the one extreme, there is Japan, which is among the strongest economies in the world. On the other extreme, there are the South Asian countries such as Nepal, Bangladesh, and Pakistan who are among the least-developed economies. In between, there are the newly emerged economic powers, the so-called little dragons: Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea. There are the two giant economies: China and India; both are still in the ‘developing’ category, but are growing rapidly. Then there are the other South East Asian nations, once called ‘advanced developing economies,’ Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, and to some extent, Indonesia. Other nations have just recovered from the inefficiency of planned economies: Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Mongolia, and more recently, North Korea.

The economic strength of these nations affects their education systems in at least two dimensions. The economy constrains the resources available, and hence affects the supply of education. The economy also carries with it manpower structure and manpower requirements that affect the demand for education among the population. However, a special feature of education systems in Asia is that strong cultural elements often override economic conditions and enable many Asian nations to develop their education systems beyond that which the economy could seemingly warrant. Again, typified by China and India, followed by Sri Lanka and Mongolia, many Asian systems demonstrate a very strong literacy rate and enrolment ratio, when compared with systems in other parts of the world.

Most of the economies in Asia have seen positive growth in the last two decades of the twentieth century, despite intermittent interruptions by political instability or financial crises. One distinct move among such economic growth, common to the Asian economies with almost no exception, is the opening of the local market to foreign investments. This has sped up the process of globalization among Asian societies. Such a trend has tremendous implications for education, both in terms of human resources demand and of the philosophies in the development of education.

4. Enrollment In Basic Education

It was not a surprise that critical international endeavor on Education for All was launched in Asia (in Jiomtian, Thailand, 1990). Asia hosts the largest student population in the world. Among others, China and India alone host a total of 250 million primary school students, which is more than one-third of the world’s students in primary education.

Population is always an issue in Asia. Population poses two types of problems for the education system: scale and growth. The sheer scale of the population in some of the Asian countries has made access to education an almost formidable problem. In addition, the problem is amplified by the rapid growth of the population in some nations.

There are very small systems of education in Asia, such as that in Brunei with around 40, 000 students, and the Maldives, which has around 50, 000, but they are not typical of Asian systems.

China and India host the two largest systems of education in the world, with primary school populations of around 140 million and 110 million, respectively. In both countries, the policy emphasis in the last two decades of the twentieth century has been on expansion of access to basic education. Both countries have launched major expansions of basic education since the mid-1980s (1985 in China, and 1986 in India). Both have demonstrated spectacular improvements in access and school attendance; however, both countries are still struggling with access problems because of the size and growth of the population.

In China, there have been rigorous measures of birth control, which have effectively slowed down the growth in the population. There has also been rather successful mobilization of community resources in the building of schools. Hence universal attendance is achieved in most parts of the country. The national enrolment ratio for primary education, age 6–12, has been over 97 percent. However, there are pockets of population where either the economy is underdeveloped or the minority culture does not accept formal schooling as it is. There are both supply and demand problems of even basic education within these pockets. It has to be borne in mind that with the vast population in China, even a small percentage would mean millions of children out of school.

In India, there has been an unprecedented increase in the scale of basic education. There has also been great success in mobilizing nongovernmental organization of education, particularly in the nonformal sector. However, the increase in access is often offset by the rapid growth in the population. In the past two decades, India has demonstrated spectacular expansion in the number of children in schools, yet there is a decrease in the enrollment ratio because of the even faster growth in the population.

Both China and India face challenges of school drop-out. There are broadly two causes of school drop-out: (a) inability of the families to bear the private costs of schooling, and (b) income-earning economic activities that distract children in their teens from schools. In China, this is more serious in rural areas of the newly prospering economies, where there is usually a drastic increase in the private costs for formal schooling, and where there are plenty of other opportunities in economic activities for the young. This is particularly serious in the final years of the nine-year compulsory schooling. In India, school drop-out is also more serious in the final years of the eight-year basic education, and occurs mainly in rural villages where schooling does not promise foreseeable employment opportunities in the modern sector.

The problems facing China and India are not limited to those two giant countries. Indonesia, for example, hosts a student population of more than 26 million. Although Indonesia does not have a vast area compared with China and India, its over 600, 000 islands have made universalization of basic education an even more formidable task. Other countries such as Pakistan and Bangladesh share the problem of rapid population growth.

Population and access are less of a problem in the more developed economies. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore have seen universal or near-universal basic education since the 1970s. The demographic situations in these societies are fairly stable; the economy poses demand for more education, and both the public and private costs are largely met with little difficulty.

Low female enrollment is a serious issue in many South Asian systems of education. It is also an issue in Japan and Korea at tertiary education level, very much because of the social expectations for women. In most other societies in Asia, there is a general increase in the percentage of female students in higher education. In some systems, such as Hong Kong and Taiwan, there are more female university students than male.

5. Schools And The Curriculum

Schools are a relatively new concept in many Asian countries. Before the school model was borrowed from the West, education took place as private tutoring, or within the temples. Still, in many Asian countries, particularly those where the population is strongly Islamic or Buddhist, education or learning is a concept that goes far beyond schools, and schools are seen only as training geared for the modern sector.

Unlike in the West, where the early schools were largely associated with the church, schools in Asia were started deliberately separate from the traditional religions. In most of the Asian systems, strong government intervention in the school system was only a post-World War II phenomenon. In the Asian context, there was the Karachi Declaration of 1962, which urged all countries in the region to achieve universal basic education within 20 years. In the decades that followed, universal education was the policy goal in most Asian countries, although the target goal of universal basic education still remains a remote vision in many countries.

The concept of a school varies from society to society. Physically, schools in Asia may vary from modern concrete buildings, which are not very different from any urban school in other parts of the world, to makeshift bare shelters, with the blackboard as the only symbol of a classroom. In the mid-1980s, there was a movement in China to supply each student with a desk and a chair. At exactly the same time, India launched the ‘Operation Blackboard’ in order to equip each class with a good blackboard.

There have been success stories of mobilization of local communities in building and running schools. This is now common practice in China, India, Pakis- tan, and Bangladesh, and is well regarded among the developing world.

Asian classes are relatively large by world standards. It is not unusual to see classes of over 50 or 60 students, at both primary and secondary levels. Such classes may be seen in relatively underdeveloped rural areas in South Asia, but are also common in developed urban cities in Korea, Japan, and the Chinese communities. In many cases, the large class is seen as a necessary community for collective learning, rather than a matter of economy.

Most of the Asian systems of education maintain a traditional curriculum. Few systems in the region have seen fundamental changes in the curriculum, and the modes of teaching or learning. Typically, schools teach the national language and mathematics as the core subjects, plus a foreign language, which since the 1980s has been predominantly English in almost all countries.

Among others, most of the systems in South Asia place a high value on the English language, and the societies use English as their language for wider communication among different language groups within the countries.

The Asian schools, East Asia and South Asia in particular, have a strong tradition in mathematics. This has made the East Asian systems of education envied by many outside the region, who regard mathematics as the most reliable evidence for student performance. The high level in mathematics learning is sometimes regarded as contributing to the success of the East Asians and South Asians in the American Silicon Valley, or the recent championship of India in software industries.

However, the Asian systems of education are also known for the frequency and intensity of examinations, both inside and external to schools, and the pressure therefore brought upon students. Private tutorials are common in many Asian countries. In East Asian societies, private tutorials are formalized in after-school tutorial schools. Typified by the juku in Japan, a large percentage of students attend tutorial schools as a normal part of their lives. In Korea, the tutorial classes start even earlier than schools in the morning. The examinations are often seen by educators as distorting the aims and relevance of learning. The reduction of adverse examination pressures has been the major theme in recent educational reforms in China, Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

Nonetheless, the examinations play a crucial role as quality controller, and have contributed to the extraordinarily small variance among students’ achievements. This has often lent itself to supporting movements for national assessments in some Western countries.

In most of the strong cultures in Asia, there was also a strong oral tradition in imparting knowledge. This has been translated into reading, reciting, memorizing, and copying, which are a large part of school activities. Such a tradition is a common point of reform in China, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Meanwhile, there are also recent discoveries, e.g., ‘rote learning’ could be a particular way of learning, and practicing is seen as an alternative path to understanding.

There are also strong elements of ‘moral’ education in Asian schools. They are implemented either through religious or ethics education, in schools that are sponsored by religious bodies. Even in secular schools, it is regarded as essential to have elements of education in moral values, attitudes, and conscience, and these are often more important than the cognitive development of students. Such moral education is fulfilled through formal lessons (such as in China, Singapore, and Taiwan), internal publicity and communications (such as campaigns, assemblies, or media within the schools), and extracurricular activities. In many Asian systems of education, the schools pay particular attention to a large variety of extracurricular activities as a way of training of student leadership or social awareness.

6. Challenges Of The Knowledge Society

The coming of the knowledge society has posed new challenges to the Asian systems of education. Most of the Asian economies have seen a rapid growth in the service sector that demands educated human resources. In many major cities in Asia, the ‘white collars’ have exceeded the ‘blue-collars’ and there is little room for uneducated ‘cheap labor.’

In these circumstances, the traditional high respect for education in Asian cultures has become a blessing, and that has been witnessed through the strong community support for basic education in many Asian countries in the last few decades of the twentieth century. Most Asian societies have no phobias about modern technology, and that attitude assists the development of learning technologies and lifelong learning.

The systems have inherited strong cultural traditions that place high importance on the development of the person. That is another strength, given the emerging emphasis of ‘social competency’ or ‘character education,’ which is increasingly seen as essential to a society where acquisition of knowledge is no longer seen as the major function of education.

However, the strong tendency to conformity in the systems, which has led to rigidity in the curriculum and uniformity in expectations, might pose a challenge to the Asian systems. There is a perceived need to facilitate and enhance diversity and creativity among the younger generation, and this is on the agenda of educational reform in many systems of long tradition in Asia.

Bibliography:

- Unesco 2000 World Data on Education, Unesco