This sample education research paper on arts education features: 6100 words (approx. 20 pages) and a bibliography with 43 sources. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The 19th and 20th centuries saw policy makers and practitioners give scant attention to K-12 arts education (Boyer, 1983; Efland, 1990). Horace Mann failed to add art to Massachusetts’ curriculum (Efland, 1990), and the Committee of Fifteen’s recommendation of 60 minutes of drawing per week for elementary schools in 1895 barely surpassed the absence of arts in the Committee of Ten’s proposal for secondary schools in 1893 (Tanner & Tanner, 1990). Boyer’s (1983) study of American secondary education a century later found the arts “shamefully neglected” and “rarely required” (p. 98). Unfortunately, art curricula have apparently regressed since the 2001 passage of the federal No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB); a Center on Education Policy report (2006) concludes that this legislation has led to a 22% reduction of instructional time for art and music.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

In this research-paper we present our definition of art curriculum and argue that art education should receive greater emphasis and balance during the 21st century. We provide a brief review of the history and major conceptualizations of arts education during the 19th and 20th centuries. We then provide rationale for including arts in K-12 schooling and discuss art standards and art assessment. Finally, drawing from our experiences as K-12 practitioners, we propose a realistic perspective for creating K-12 art education programs.

Definitions

Curriculum has been variously defined (Jackson, 1992), leading to conceptions that are narrow (“a fixed course of study”), broader (“all organized experiences that occur under the direction of a school”), and broader still (“all experiences, planned and unplanned, under the direction of a school”). Theorists have expanded these definitions to include such facets as the hidden curriculum, the written curriculum, and the learned curriculum. Because different definitions lead to different topics, we define the arts curriculum as “the planned course of K-12 student learning outcomes (e.g., knowledge, conceptual understanding, and critical thinking skills) in visual art, dance, music, and theater.” For this research-paper, we focus on the visual arts, expanding beyond planned student learning outcomes to explain how visual arts curriculum might be more strategically derived, vibrantly presented, and learned.

Historical Perspective

The late 19th century and the 20th century saw art education moving toward wider acceptance as part of the K-12 curriculum. Progress was slow and unstable, however, especially during times of financial or perceived educational crisis. Early advocates such as Lowell Mason, Horace Mann, and von Rydingsvard were influential in moving the arts forward (Efland, 1990; Wolf, 1992). Mann sought to create schools where all students beyond the privileged could study drawing, music, and natural objects. Mason produced songbooks and popular articles related to music, and von Rydingsvard sold mass-produced art reproductions to schools along with manuals on how to use them to teach various virtues. Wolf (1992) notes that arts education was therefore accepted not as a field of study but rather as “a tool or an occasion for producing citizens, a way to smooth, to civilize, and to inculcate . . .” (p. 948).

School leaders also responded to the need to create more practical and attractive programs for youth. Grammar schools gave way to infant schools, academies, and public schools aimed at enrolling every adolescent—not just those few attending university. Growing demands for workers (Tanner & Tanner, 1990), recognition that the Latin grammar school was too antiquated for serving societal needs, and the ostensible interest in creating a common school that conserved cultural values led arts curriculum to be based more on their service to “virtue, religion, citizenship, and industry . . .” than as a field of study (Wolf, 1992, p. 948).

In contrast to Boyer’s (1983) finding that art was a rare requirement, a larger survey by Lehman and Sinatra (1988) found that art and music were taught in 90% and 93% of the schools, respectively, and that 22 states by 1989 had art graduation requirements. An Education Commission of the States (2007) report found that 35 states now have an arts requirement and 23 states require at least a semester of art credit alone. Rose and Gallup (2006) found that public interest in broadening the curriculum is currently high, as 58% of those polled nationally and 63% of public school parents responded that a wide variety of courses should be favored over fewer but more basic courses—a substantial increase in both cases from 44% in 1979.

Conceptualizations of Art Education

Wolf (1992) identifies four major conceptualizations in the evolution of arts curriculum: (1) arts education for craftsmanship, (2) arts education for creativity and self-discovery, (3) arts education for developing symbols and thinking, and (4) arts education for apprenticeship. Wolf (1992, p. 947) explains that this conceptual evolution involves the arts as a distinct form of knowledge; a press for the arts to become part of a common curriculum for all learners; research showing there to be sequences of development typical of art learners; the importance of teaching and learning artistic knowledge and skills; and interest in connecting art education classrooms to practices found in studios, museums, performance halls, and universities.

Arts Education for Craftsmanship

Wolf (1992) explains that early art educators tended toward efficiency methods used in industry and priority curriculum areas such as reading and mathematics. Early art textbooks were dominated by elements of design, routine exercises, and a skills-based sequence of activities. When Walter Smith became Massachusetts’ art director, his program focused on “drawing skills useful to industry” and “practicing isolated elements of design [curves and designs present in fabric, ornaments, and wallpaper] repetitively until they achieved a machinelike dependability” (Wolf, 1992, p. 948). According to Wolf, this curriculum provided students drawing tools to become skilled workers and to enhance their social status above what might have been predicted, without much personal expression or creativity.

Arts Education for Creativity and Self-Discovery

As the 20th century began, arts education reflected such social interests as evolution theory, psychoanalysis, industrial reform, as well as new artistic directions such as romanticism, cubism, and the arts and crafts movement— forms linked to individual imagination, spontaneity, and expression. Arts education became “a safeguard against the routine, the regular, and the predictable, something like an occasion, or a medium, for the development of creativity” (Wolf, 1992, p. 949). Now students were seen as free-spirited artists, discoverers, and natural inventors of self-expression—not students to be taught to draw and copy. Cultural changes and progressive education, derived in part from child-centered practices, led art educators to argue that the arts played a unique role in the curriculum—contributing to personality development and the creativity needed to become effective citizens. During this time, art teachers evolved from mentors of drawing skills to facilitators who provided the studio, materials, and occasions for various projects.

Arts Education for Developing Symbols and Thinking

Uneven results from progressive education, cultural shifts from behaviorism and romanticism, reaction to Russia’s Sputnik success, and research that documented major patterns of language acquisition and cognitive and moral development led the view of arts education to shift from creativity and individualistic expression to a view of the arts as “earned conceptual development” (Wolf, 1992). Wolf writes that researchers and educators asserted that students slowly constructed (not discovered) rule systems embedded in the arts of their culture and that, hence, the arts were not simply occasions for self-expression and discovery but more a matter of learning, deserving careful instruction.

Visual arts researchers (e.g., Lowenfeld & Brittain, 1975) provided strong descriptions of the developmental stages, leading to implications for art instruction. Indeed, an understanding of these stages and the provision of active and developmentally appropriate instruction and materials, as well as peer interactions aimed at cognitive growth, partially replaced the earlier conceptions of art education. Art education now became focused on listening and looking at art, rule-governed thought, and efforts to develop students’ ability to read the language and history of the arts.

Arts Education for Apprenticeship

The final conceptualization of arts education grew largely from three major controversies about educational practice that developed between 1960 and 1990: (1) the role of explicit teaching and development; (2) difficulties related to canons of art and intellect; and (3) the role of thoughtfulness in artistry. Wolf (1992) explains that concerns now centered on what occurred naturally rather than on what educators specifically wanted students to know or be able to do—”What occurs ‘naturally’ is not necessarily the foundation for a curriculum. Development establishes only a footing—it cannot dictate matters of value” (p. 953).

A second critique stemmed from disagreements about what constituted intellect and art, and the role of art history, art criticism, and aesthetics. Traditional definitions of IQ and ways of knowing were challenged by scholars. The need for a multicultural perspective in art history was expressed as well as whether arts education should be “rooted chiefly in knowing how to make art, or whether it should expand to include knowing about” art (Wolf, 1992, p. 956). It was argued that art appreciation increases when we understand the context of the work.

Research and theory on critical thinking also influenced the new conception of arts education (Wolf, 1992, p. 955). The mind was reconceptualized from that of a memorizer to that of a planner, reflector, and thinker about thinking (metacognition). This led to interest in narrowing the gap between thinking in typical school settings and thinking that occurs in authentic artistic contexts. Numerous researchers pointed to problems associated with teaching content and basic skills devoid of applications, and some noted that typical public school art was marginal in qualitative depth.

These three discussions led to the viewpoint of student as apprentice. According to Wolf, efforts to link school arts with expert practice generated two widely different curriculums: (1) discipline-based art education (DBAE), and (2) ARTS PROPEL. The DBAE approach focuses on introducing students to four major areas of artistic knowledge—art making, art history, art criticism, and aesthetics—and aims to develop visual literacy, or the ability to derive meaning from works of art. Students who learn components of a DBAE curriculum will gain skills in identifying key visual characteristics of artworks such as historical connections, use of art elements and principles, and expressive properties. Dobbs (2004, p. 706) describes the DBAE student as one who is able to converse about artwork in terms of elements and principles, how they were made, and what they mean in the historical and cultural context. This student would also be able to identify quality and intentionality in works of art and be able to conceive, design, and create such.

Teachers using PROPEL (designed by researchers at Harvard Project Zero and Educational Testing Service) engage students in doing the work of the art field with extensive portfolio development through sustained involvement (Wolf, 1992, p. 957). This approach allows latitude for highly imaginative and innovative works and deep understanding of the work. This final conceptualization argues for mentors capable of modeling the performance and metacognition of seasoned artists in the field, authentic work in the arts, and restructuring of many present art education practices such as longer class periods, virtual and actual museum tours, and in-depth critiques.

Purposes of Art Education

Some policy makers may believe art education is a frill and intellectually inferior, but quality programs incorporate numerous higher-cognitive skills, some of which are untouched by other academic disciplines. The development and application of these advanced cognitive skills make the arts especially valuable for 21st-century education. The lack of understanding about substantive purposes of art can be traced to three of education’s intellects: Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky, and Benjamin Bloom. Piaget’s (1963) description of the intellectual development process focused on science and mathematics, giving less importance to the arts. Piaget’s theory relegated the arts (nonpropositional thinking) to lower-order cognition, and arts education has suffered from this assumption. Vygotsky’s (1962) theory suggests that knowledge is learned through forms of social mediation. Vygotsky described how knowledge is internalized but not how individuals construct through imagination and intuition. Bloom’s (1956) widely accepted taxonomy of instructional objectives has reified the cognitive, affective, and psycho-motor domains. Consequently, the arts have traditionally been grouped with noncognitive domains and afforded lower intellectual status (Efland, 2002).

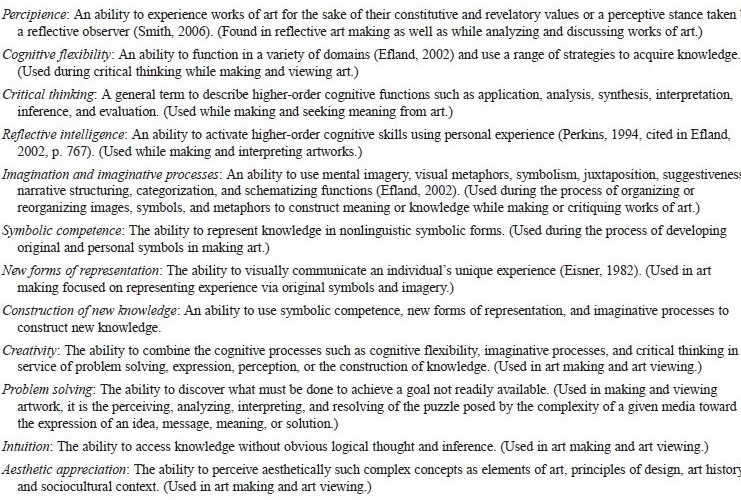

At the very least, art courses must attempt to include higher-order thinking skills as curriculum objectives and as the focus of assessment before claiming ownership and responsibility for them. These cognitive skills overlap and involve aspects of each other in various ways; therefore a hierarchical taxonomy is not suggested. Table 40.1 describes the higher-cognitive purposes of art education highlighted by scholars Schwartz (2000) reinforces the value of critical thinking common to arts education by asserting its overarching political usefulness of promoting, supporting, and maintaining the aims of a democratic society. Engaging critically with works of art, students practice the ideal democratic skills of suspending judgment, deliberation, debate, decision making, and other values such as tolerating different points of view.

Table 1 Higher-Cognitive Purposes of Art Education

Standards

Standards (shorthand for the more complete phrase academic content and performance standards) are what students are generally expected to know or be able to do. Standards, therefore, are “statements about what is valued” (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics [NCTM], 1989, p. 2). Tucker and Codding (1998) emphasize that to be useful, standards need to be specific, realistic, expressed in a common framework across the disciplines, and linked to reliable assessments. Usually, standards are supplemented with benchmarks that clarify the specific content or skills to be mastered and how such might be taught and assessed (Tucker & Codding, 1998). Unfortunately, standards vary widely among states, disciplines, and professional organizations. Furthermore, many state standards are unclear about intended outcomes for students, and many states simply have a glut of standards that render them highly problematic to teachers. Numerous scholars have stressed the practical need to make hard choices about what knowledge and skills are most essential so that adequate time may be given to instruction for learning and mastery. Moreover, many practitioners and scholars, while applauding the high expectations and noble goal of a single, world-class set of curriculum standards, assert that one size rarely fits all in public schooling, especially in the highly heterogeneous culture of the United States.

The document National Standards for Arts Education: What Every Young American Should Know and Be Able to Do in the Arts was created in 1994 by the Consortium of National Arts Education Associations. These standards for dance, music, theater, and visual arts were endorsed by over 50 professional organizations and supported by over 25 others. Used as a model by many states as they crafted their state art standards, the National Standards for Arts Education includes 6 standards and 44 benchmarks or achievement standards: 15 at Grades K-4; 14 at Grades 58; and 15 at Grades 9-12. An additional 10 benchmarks for demonstrating advanced art achievement are drawn for Grades 9-12. The 6 common standards are (1) under— standing and applying media, techniques, and processes; (2) using knowledge of structures and functions; (3) choosing and evaluating a range of subject matter, symbols, and ideas; (4) understanding the visual arts in relation to history and cultures; (5) reflecting upon and assessing the characteristics and merits of their work and the work of others; and (6) making connections between visual arts and other disciplines.

Authors of the National Standards for Arts Education explain that standards can make a difference in program quality and accountability, ensuring that arts education is focused, disciplined, and able to assess program results. They argue that the standards are sequenced, comprehensive, and aimed at developing “the problem-solving and higher-order thinking skills necessary for success in life and work . . .” (Consortium of National Arts Education Associations, 1994, p. 6). They conclude that the standards may be influenced by various educational changes during the 21st century as school days and years are restructured and as the goal of education changes from educational progress by grade level to student mastery.

Art Assessment

Assessment is broadly defined as “the systematic investigation of the worth or merit of some object (program, project, materials)” (Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation, 1981, p. 12). Assessment informs our focus on agreed upon standards, clarifies what we need to reteach and whether our instruction needs improvement, and enables larger program evaluation and accountability by administrators and policy makers. Improving the use of valid and reliable assessments would contribute to the legitimacy of art well into the future. Traditionally, K-12 art education has relied upon authentic forms of assessment. Teachers subjectively evaluate projects and portfolios through informal means or performance-based rubrics. Art educators worry that standardized assessment will artificially quantify key aspects of art such as imagination and creativity (National Assessment Governing Board, 1994). They also worry that adding standardized measures, especially those of lower-level knowledge and skills, will shift the focus inordinately to these lesser aims. Interest in accountability and addressing concerns about the biases and far-ranging goals of traditional authentic assessments have led to steady advances in art assessment, but the lack of inclusion in high-stakes accountability efforts diminishes the importance of art for administrators, educators, and the public (Boughton, 2004).

Portfolio assessments, widely used in higher education for assessment and admission to art programs, are the major tools for measuring success in the College Board’s AP Studio Art program (1980) and the International Baccalaureate’s (IB) Art and Design program (Boughton, 2004). These programs are exemplars of large-scale portfolio assessment, creating objectivity by training portfolio reviewers in procedures, standard-setting rubrics, and scoring guides; however, reliability is only ensured by the pooling of separately scored sections of the portfolio (Myford & Sims-Gunzenhauser, 2004). The following authentic forms of assessment are assumed to measure the higher-cognitive skills sought by most art curriculums: large-group critiques, reflective or interactive journals, small-group critiques, and student-pair critiques (Freed-man, 2003). In nearly every case, for art assessments to rise to higher levels of validity and reliability, these typically informal assessments should gather written or oral records, however impractical. In response to a perceived need for such standardization, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (Myford & Sims-Gunzenhauser, 2004) created a large-scale standardized assessment of art making based on the 1997 Arts Education Framework. This assessment, a timed drop-in format with both multiple-choice and open-ended items, was designed to capture the complex nature of art making, interpreting, and critiquing as well as assessing specific content knowledge. This framework provides a meaningful model for how states might develop standardized art assessments.

Critics of standardized testing in art have traditionally provided strong opposing philosophical positions, fearing loss of student freedom and homogenizing effects (Bough-ton, 2004; Gardner, 1996). Ironically, standardized tests carry the additional risk of informing art educators about that which they may not want to know, thus increasing their responsibility for teaching and learning in areas for which they have less preference. It is certainly easier to maintain an imbalanced art education curriculum related to individual teacher interests or preferences; however, by not participating in a balanced assessment program, high-stakes testing, or both, art educators risk maintaining their subject at a marginalized level. Of course, the issue of art assessment is always linked to fundamental curriculum questions about the purposes of K-12 art education.

Assessments of higher levels of cognition are difficult to construct, time-consuming to use, lacking in reliability, and therefore uncommon. Many argue that if these skills are assessed, then art teachers will more frequently teach them and see their presence increase. Each of the following higher-level skills can be assessed authentically in formal and informal ways, even using objective and standardized approaches that are potentially more valid and reliable. For many skills teachers may simply borrow authentic assessment methods from other disciplines such as writing and literature. Oral discussions are the preferred form of demonstration, but in the interest of reliability, writing samples are recommended. With the exception of creativity and construction of new knowledge (because of their breadth and complexity), higher-cognitive skills such as those reviewed in Table 40.1 may be assessed with the following strategies: objective multiple-choice questions with stimuli prompts, student writing samples, critiquing works of art or visual culture, performance-based activities aimed at solving particular problems, and using metaphors and personal symbolism in art making.

If K-12 art educators are to demonstrate their subject’s true academic value and claim the cognitive territory that they own, they must move toward using valid and reliable measurement. To do this, ambiguous constructs such as imagination, creativity, and expression must be unwrapped and operationally defined—thus becoming objects of curriculum and assessment. Developing objective and standardized measures for areas previously untouched in the arts is not as difficult or as dangerous as it may seem. Research in cognitive psychology may enable art educators to see ways in which their constructs may be more operationally defined and objectively measured. Although it is beyond the scope of this research-paper to operationally define these constructs or to describe highly specific standardized assessment tools, we suggest using more objective approaches for assessing higher cognitive functioning in art. Whether the curriculum bias tends toward emphasizing traditional art making (Burton, 2001), imaginative cognition (Efland, 2004), competence in understanding visual culture (Freedman & Stuhr, 2004), or other purposes, these aims use similar cognitive functions. Therefore, assessment of the higher-level cognitive functions in art with increasing standardization and objective measures is complementary to each of these curricula.

A Practical Perspective

The intent of our viewpoints, knitted after much reading, reflection, and collegial interaction, is to propose a practical picture of art education during the 21st century—what we hope to become as art teachers and what we advocate for colleagues and policy makers who influence how art education evolves in states and local school districts. Under the common grade structures of K-5, 6-8, and 9-12, we present 7 reforms that are needed to improve art education during the 21st century: (1) an emphasis on art for all K-12 students; (2) an emphasis on mastery of art fundamentals; (3) an organizational structure for art teaching at each level; (4) a balanced curriculum; (5) an approach to assessing art education; (6) a district and collegial orientation to art program development and exhibition; and (7) a call for research on the role of art in promoting learning, individual expression, and a more tolerant and nurturing society.

Art for All K-12 Students

Surveys show that far too many students are not enrolled in art classes. The 1977 National Assessment of Progress in Education (NAPE) found that only half of a national sample of eighth graders had taken or were taking art (Burton, 2004). Moreover, this same NAPE survey showed there was “no significant difference in the accomplishments of youngsters who were currently studying art and those that were not,” that “94% of pupils failed to demonstrate even moderate creative abilities,” and that “instruction had a negligible effect on the overall outcomes” (Burton, 2004, p. 562; Persky, Sandene, & Askew, 1998). Given these data and the aforementioned purposes of art education, we recommend that all K-12 students learn the fundamentals of art through participation in a systematic, standards-based, and mastery-oriented art program. As Burton (2004) notes, “the NAPE results together with other formal empirical studies lend credence to the small effects of art instruction on children’s lives” (p. 568). Art education will continue to be marginalized and student outcomes will continue to be paltry until we aim all students toward mastering art fundamentals.

Mastery of Art Fundamentals

Studies of effective schools and effective teachers have consistently found that high student achievement is correlated with “expectations regarding their abilities to master the curriculum” and teachers providing “opportunities for students to practice and apply [new content]. They monitor each student’s progress and provide feedback and remedial instruction as needed, making sure the students achieve mastery” (Good & Brophy, 2000, pp. 377-378). In view of these important findings, consistently confirmed by our teaching and learning experiences, we recommend a strong orientation toward a limited curriculum that is consensually derived, taught in depth, objectively assessed, retaught when necessary, and mastered to a point that the knowledge, concepts, and skills may be used during applications, subsequent learning opportunities, and postsecondary real-world experiences. We are convinced that for progress in art learning and application to increase, mastery of art fundamentals must become central.

Improving the Organizational Structure

Art teaching occurs within an organizational structure that answers questions such as, Who teaches the art curriculum? Who gets the art curriculum? For how long do they get the art curriculum? and What materials, equipment, and real-world resources are available? Answers to these and other structural questions vary widely among and within states, districts, and schools. Indeed, while rare, there are likely some enlightened schools, districts, and states that presently exceed the following structural recommendations.

At the K-5 level we recommend that certified art teachers engage all elementary school students in the district art curriculum for no less than 500 minutes per year (e.g., once a week for 20 minutes, once a month for 60 minutes). Elementary teachers rarely have the in-depth training required for a quality art education program, and their professional development is aptly placed on the more valued areas of teaching reading, mathematics, science, and social studies. This modest commitment would enable elementary students to accrue 50 hours or more of focused art instruction and hence carry forward to their middle schools a solid foundation of knowledge, concepts, and skills in art making, art history, and art critique including aesthetics and visual culture. At a minimum, where constraints preclude the use of certified K-5 art teachers, certified secondary art teachers who are most familiar with the district program should provide their elementary colleagues professional development on the essential art standards and aligned assessments and lesson plans that would enable student mastery at each individual grade or primary (K-2) and intermediate (Grades 3-5) level.

At Grades 6-8 we recommend that a certified art specialist engage all students in the art curriculum each year during their middle school careers for at least 1,500 minutes per year (e.g., 6 weeks for 50 minutes a day, 12 weeks for 50 minutes per day). This structure is reasonable given that middle school philosophy encourages exploratory programs such as band, music, technology, foreign language, and speech or drama. Such a structure would enable middle school students to experience at least an additional 75 hours of art curriculum. At a minimum, recognizing that elective and semester course structures are entrenched in many schools, a required semester course on fundamentals of art during a student’s middle school career would ensure the curriculum continuity necessary for curriculum mastery by high school graduation.

At the high school level we recommend that a certified art teacher engage all students in a full-year art fundamentals course. At a minimum, a semester course of art fundamentals would be preferable to current practices in most states. This course should encompass key knowledge, concepts, and skills related to art history, art criticism, and the making of art. Students enrolled in this art fundamentals course—likely a culminating experience for most students—should attain mastery of the identified fundamentals, setting up important prerequisite appreciation, knowledge, and understanding for success in future art courses and real-life application experiences. At all three structural levels, art teachers should be supported with adequate supplies, equipment, and resources.

A Balanced Curriculum

We see K-12 art education organized as a spiral curriculum and reconceptualized as three subdisciplines: art making, viewing (Smith, 2006), and connections. Each of these subdisciplines includes knowledge, concepts, and critical thinking skills (including application). Art making is focused on production. Viewing is focused on engagement with examining works of art, especially masterworks from art history. And connections are focused on the demonstrated relevance and utility of arts education in students’ lives outside the classroom including careers and participation in visual culture (Freedman, 2003). For parsimony, practicality, and increased relevance and student engagement, we see the need for three subdisciplines, rather than four (DBAE) or five (California Department of Education, 2004).

Art making knowledge and understanding at K-5 would center on the language of art including art elements, art principles, and vocabulary related to basic tools, techniques, media, and processes. For critical thinking at K-5, students would use various media in basic representational, metaphoric, and symbolic (Efland, 2002) approaches to perceptual, experiential, and expressive problem solving. At the 6-8 level, the curriculum should review and build upon this same knowledge and conceptual understanding with a greater emphasis on applications to projects as well as new tools, techniques, media, and processes. Projects should integrate art elements and principles (e.g., a line and shape project emphasizing rhythm and movement) along with new principles of design and advanced forms of cognition, representation, and suggestiveness such as metaphor and symbolism. Teachers should encourage critical thinking by using various media to solve perceptual, experiential, and expressive problems. At the 9-12 level, knowledge and understanding would again include the language of art along with a broadening of information about (a) basic historical styles and artists, (b) additional media and their related processes, (c) imaginative cognitive processes such as metaphor, symbolism, and other forms of representation, and (d) increasing student awareness of their own creative process and developing a personal philosophy of art. Critical thinking at this level should include an in-depth focus on suggestive, representational, metaphoric, and symbolic approaches to solving personal or commercial artistic problems. This may include students employing the same imaginative cognitive approaches and creative processes as those used by specific artists or styles in art history.

Viewing knowledge at the K-5 level would include the language and definition of art, media categories, artists, artistic styles, and the masterworks of art history. Concepts would include exposure to and developing a familiarity with art exemplars, artistic styles, functions of art, and how to look at art in a stepwise process—for example, description, analysis, characterization, and interpretation (Broudy, 1987; Smith, 2006). Critical thinking skills are facilitated while analyzing and interpreting works of art and using an inquiry-based method of associative questioning (Freedman, 2003). At Grades 6-8 teachers would extend students’ knowledge and understanding of the definitions and language of art, media categories, artists, artistic styles, and masterworks, as well as add information about the chronology of art history. Conceptual outcomes would include a sense of historical continuity and learning about various artists’ styles, approaches, and purposes. There should be continued emphasis on fully understanding the stepwise critiquing process for examining art history exemplars, student work, and visual culture. At the 9-12 level, viewing knowledge would further emphasize the language and vocabulary of art, the critique process, and the chronology and deeper contextual factors of art exemplars, styles, and artists. Critical thinking approaches at this level would include more group, partner, and self-critique using inquiry-based methods of associative questioning directed toward art exemplars and students’ own and other’s works for various purposes.

Connections at the K-5 level are created by presenting students knowledge and concepts about art careers and the presence of art in their everyday visual world. Critical thinking would include analyzing visual culture as well as using knowledge and concepts for creating products in other academic subjects and real-life applications. At Grades 6-8 teachers should focus on increasing students’ knowledge of art careers and art in visual culture, including the influence of visual culture on identity and values. Critical thinking activities would center on analyzing artifacts of visual culture and more advanced applications of art to other areas of students’ academic and personal lives. At the 9-12 level, students would develop knowledge and concepts related to additional careers in the arts, artifacts of visual culture, suggestiveness in visual culture, and imaginative cognitive processes. The concepts would include imaginative cognition and critique processes, including visual culture’s influence on issues such as identity, values, and contemporary problems. Critical thinking would be used for inquiry, problem solving, examination of contemporary problems and issues, and evaluation of visual culture in other areas of students’ academic and personal lives.

Assessing Art Education

We recommend that art assessment during the 21st century become aligned with essential standards—those fundamentals identified as most crucial to subsequent learning and applications in and out of school. Unlike typical current practice, whereby standards are nonexistent or unrealistic and objective assessment is seriously lacking, we advocate creating valid and reliable measures of all fundamental standards at each of the three levels. At Grades K-5, we recommend an annual assessment that provides educators information about whether students are mastering important art concepts and skills. At Grades 6-8 and 9-12, we recommend midcourse and end-of-course assessments that identify student progress and outcomes of art learning. Such assessments should include a broad range of item types, appropriate to the standard, including items that assess higher levels of cognition. Further, results of such assessments should become the object of in-depth analyses aimed at program and instructional improvements, using both cross-sectional and longitudinal data. While many districts have now identified essential standards and created assessments to measure curriculum priorities in reading, English, mathematics, science, and social studies, we think such curriculum and assessment work should be extended to art and other important areas (e.g., music, health, technology, public speaking).

A District and Collegial Orientation to Program Development

Vital to developing and implementing most of our recommendations is a process for creating quality, context-specific standards, assessments, and program and instructional improvements: a structure of district leadership and support for collegial interaction. More than three decades of research have shown that school and classroom improvements are linked to collaborative efforts aimed at curriculum development and implementation, monitoring of student progress, and improvement of instruction (e.g., Little, 1981; Rosenholtz, 1989). Our personal experiences (Mason, Mason, Mendez, Nelsen, & Orwig, 2005) with strong district leadership focused on teacher-led efforts to develop essential standards, standards-based assessments, and standards-based instructional improvements have demonstrated the power of integrating research-based theory with the craft knowledge of teachers.

We recommend that district leaders use rotating teams that ultimately involve all teachers to develop essential art standards and assessments of these standards. Such work not only provides staff development in curriculum and assessment construction but also creates ownership and commitment toward high-fidelity implementation. District and school leaders should build calendars that enable all teachers to work on annual curriculum and assessment refinements, guides for pacing instruction, and common lesson plans that have theoretical potential or demonstrated success in ensuring student mastery of essential knowledge, concepts, and skills. Work presently underway at our high schools, based on frameworks articulated by Reeves (2002, 2006) and others (e.g., Ainsworth, 2003; DuFour, Eaker, & DuFour, 2005) demonstrate that development of such essential standards, assessments aligned to these standards, and focused teaching and reteaching can lead to significant gains in student achievement across all curriculum areas.

A Call for Research on Art Teaching

Our review of the literature on art education, though far from extensive, noted too little research on how various curriculums, programs, or instructional strategies influence important outcome variables such as imagination, creativity, and problem solving. We also came across no research on the effectiveness of different assessment strategies for improving learning. Descriptive, correlational, and experimental studies would be instructive in the areas of using state standards, essential standards, standards-based assessments, mastery-oriented learning units, and teacher-led collegial exchange aimed at sharing craft knowledge to improve student learning of art concepts and skills. Given our interest in the role of authentic learning, situated cognition, and public art, research on programs based on these components would be informative. Research, however, should be comprehensive, measuring an array of dependent variables so as to identify whether focusing on particular curriculum areas leads to trade-offs in other areas. We believe a well-constructed curriculum that balances essential knowledge and concepts with deep applications and critical thinking skills related to identified art fundamentals would be mutually reinforcing and bring about high levels of learning overall. Finally, nearly five decades of process-product research in basic skill areas have provided educators many findings that can be used to improve instruction and student outcomes. We saw no evidence of this type of research in our review of the art education literature, likely because dependent measures in many areas of art education are at an undeveloped stage or shy of appropriate validity and reliability. As measurement tools become available, however, such research would be valuable.

Conclusion

Art education has historically received too little attention in the K-12 curriculum, and recent state and national initiatives under NCLB have only served to diminish this dismal picture. In this research-paper we argue for a stronger emphasis on art education during the 21st century—an emphasis that includes stronger curriculum balance, mastery of identified art fundamentals, and use of more valid and reliable assessments to improve instruction and student learning. Art education develops many higher-order cognitive functions valuable for business, personal expression and appreciation, and promulgation of a thriving and nurturing democratic society. These important higher-cognitive functions are absent or rare priorities in other areas of the K-12 curriculum. Policy makers as well as educational leaders should understand the true cognitive value of the arts in order to establish art programs that contribute these positive effects to all U.S. students and future citizens. When curriculum reflecting higher-order cognitive skill development becomes the standard, education in the arts will be understood and valued for its full potential and possibility.

Bibliography:

- Ainsworth, L. (2003). Power standards: Identifying the standards that matter the most. Denver, CO: Advanced Learning Press.

- Bloom, B. S. (Ed.). (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: Cognitive domain. New York: McCay.

- Boughton, D. (2004). Assessing art learning in changing contexts. In E. W. Eisner & M. Day (Eds.), Handbook of research and policy in art education (pp. 585-605). Mah-wah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Boyer, E. L. (1983). High school: A report on secondary education in America. New York: Harper & Row.

- Broudy, H. (1987). The role of imagery in learning. (Occasional paper 1). Los Angeles: Getty Center for Education in the Arts.

- Burton, D. (2001). How do we teach? Results of a national survey of instruction in secondary art education. Studies in Art Education, 42(2), 131-145.

- Burton, J. M. (2004). The practice of teaching in K-12 schools. In E. W. Eisner & M. D. Day (Eds.), Handbook of research and policy in art education (pp. 553-575). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- California Department of Education. (2004). California framework for the visual arts. Sacramento, CA: Author.

- Center on Educational Policy. (2006, March). From the capital to the classroom: Year 4 of the No Child Left Behind Act. Washington, DC. Author. Retrieved July 27, 2007, from www.cep-dc.org/nclb/Year4/NCLB-Year4Summary.pdf

- The College Board. (1980). Advanced placement course description: Art. New York: Author.

- Consortium of National Arts Education Associations. (1994). National standards for arts education: What every young American should know and be able to do in the arts. Reston, VA: Music Educators National Conference. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED365622

- Dobbs, S. M. (2004). Discipline-based art education. In E. Eisner (Ed.), Handbook of research and policy in art education (pp. 701-724). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- DuFour, R., Eaker, R., & DuFour, R. (2005). On common ground: The power of professional learning communities. Blooming-ton, IN: National Education Service.

- Education Commission of the States. (2007). Standard high school graduation requirements (50-state). Denver, CO: Author. Retrieved from http://ecs.force.com/mbdata/mbprofall?Rep=HS01&mod=article_inline

- Efland, A. (1990). A history of art education: Intellectual and social currents in teaching the visual arts. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Efland, A. (2002). Art and cognition: Integrating the visual arts in the curriculum. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Efland, A. (2004). Emerging visions of art education. In E. W. Eisner (Ed.), Handbook of research and policy in art education (pp. 691-700). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Eisner, E. W. (1982). Cognition and curriculum: A basis for deciding what to teach. New York: Longman.

- Freedman, K. (2003). Teaching visual culture: Curriculum, aesthetics, and the social life art. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Freedman, K., & Stuhr, P. (2004). Curriculum change for the 21st century: Visual culture in art education. In E. W. Eisner & M. Day (Eds.), Handbook of research and policy in art education (pp. 815-828). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Gardner, H. (1996). The assessment of student learning in the arts. In D. Boughton, E. W. Eisner, & J. Ligtvoet (Eds.), Evaluating and assessing the visual arts in education: International perspectives (pp. 131-155). New York: Teachers College Press.

- Good, T. L., & Brophy, J. E. (2000). Looking in classrooms (8th ed.). New York: Longman.

- Jackson, P. W. (1992). Conceptions of curriculum and curriculum specialists. In P. W. Jackson (Ed.), Handbook of research on curriculum (pp. 3-40). New York: Macmillan.

- Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation. (1981). Standards for evaluation of educational programs, projects, and materials. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Lehman, P., & Sinatra, R. (1988). Assessing arts curricula in the schools: Their roles, content, and purpose. In J. McLaughlin (Ed.), Toward a new era in arts education: The Interlochen Symposium. New York: American Council on the Arts.

- Little, J. (1981). School success and staff development in urban desegregated schools: A summary of recently completed research. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Los Angeles.

- Lowenfeld, V., & Brittain, W. L. (1975). Creative and mental growth (6th ed.). New York: Macmillan.

- Mason, B., Mason, D. A., Mendez, M., Nelsen, G., & Orwig, R. (2005). Effects of top-down and bottom-up elementary school standards reform in an underperforming California district. Elementary School Journal, 105(4), 353-376.

- Myford, C. M., & Sims-Gunzenhauser, A. (2004). The evolution of large-scale assessment programs in the visual arts. In E. W. Eisner & M. Day (Eds.), Handbook of research and policy in art education (pp. 637-666). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- National Assessment Governing Board. (1994). Arts education assessment framework, 1997. Washington, DC: Author.

- National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (1989). Curriculum and evaluation standards for school mathematics. Reston, VA: Author.

- Persky, H. R., Sandene, B. A., & Askew, J. M. (1998). The NAEP 1997 arts report card: Eighth-grade findings from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (Report No. 1999-486). Washington, DC: National Center for Educational Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=1999486

- Piaget, J. (1963). The origins of intelligence in children. M. Cook (Trans.). New York: Norton. (Original work published 1952)

- Reeves, D. B. (2002). The leader’s guide to standards: A blueprint for educational equity and excellence. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Reeves, D. B. (2006). The learning leader: How to focus school improvement for better results. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Rose, L. C., & Gallup, A. M. (2006). The 38th annual Phi Delta Kappa/Gallup Poll of the public’s attitudes toward the public schools. Phi Delta Kappan, 88(1), 41-56.

- Rosenholtz, S. (1989). Teachers’ workplace: The social organization of schools. New York: Longman.

- Schwartz, D. T. (2000). Art, education, and the democratic commitment: A defense of state support for the arts. Boston: Kluwer.

- Smith, R. A. (2006). Culture and the arts in education: Critical essays on shaping human experience. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Tanner, D., & Tanner, L. (1990). History of the school curriculum. New York: Macmillan.

- Tucker, M. S., & Codding, J. B. (1998). Standards for our schools: How to set them, measure them, and reach them. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Vygotsky, L. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Wolf, D. P. (1992). Becoming knowledge: The evolution of art education curriculum. In P. W. Jackson (Ed.), Handbook of research on curriculum (pp. 945-963). New York: Macmillan.