Sample Learning To Learn Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The quest for understanding and harnessing an individual’s ability to identify, reflect upon, improve, and control his or her learning processes and outcomes, began in ancient times with the study of mnemonics (memory aids) and Socratic teaching methods. However, it is only since around 1975 that incredible progress in understanding ‘learning to learn’ and the methods that can be used to improve it have occurred. This research paper will present a definition of learning to learn followed by a brief history of the development of the study of learning to learn processes. A model summarizing much of the current research in this area will then be presented as well as a summary of the results of current research examining the effectiveness of methods for improving learning abilities and skills. The entry concludes with a discussion of suggestions for future research and conceptual development in the area of ‘learning to learn.’

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Learning To Learn Strategies

‘Learning to learn’ strategies include any thoughts, behaviors, beliefs, or emotions that facilitate the acquisition, understanding, or later application and transfer of new knowledge and skills in different performance contexts. They range from active rehearsal to help remember word lists, to the use of elaboration and organization to encode, integrate, and later recall or apply knowledge across several content areas. Learning to learn strategies help generate meaning for the new information that is to be learned. Repeating the names of the planets in order, organizing the discoveries of the great explorers by creating timelines and mind maps, comparing and contrasting the causes of World War I and World War II, are all examples of learning strategies. They all are designed to help the learner generate meaning and store the new information in memory in a manner that will facilitate integration with related knowledge and increase the probability of later recall and use, particularly in transfer contexts.

A learning strategy is also a plan for orchestrating cognitive resources to help reach a learning goal. ‘Learning to learn’ strategies have several characteristics in common. First, they are goal-directed. Learning strategies are used to help meet a standard of performance or to reach a learning goal. Second, learning strategies are intentionally invoked, which implies at least some level of active selection. The selection of one or more of these strategies is determined by a number of factors, such as a student’s prior experience with the strategy, his or her prior experience with similar learning tasks, his or her ability to deal with distractions, and the student’s commitment to his or her goals. Third, cognitive learning strategies are effortful; they require time and often involve using multiple, highly interactive steps. Because of the effort required, a student must be motivated to initiate and maintain strategy use. In addition, the student must believe that the strategy will be effective and that he or she can be successful using the strategy. Finally, cognitive learning strategies are not universally applicable—they are situation-specific. The student’s goals, the task requirements, the context, and other factors all interact to help determine which strategy may be best. To be successful in selecting and using a strategy, a student must understand under what circumstances a given strategy is, or is not appropriate.

The following section will discuss the evolution of learning to learn as a field of study and a source of applications for many students experiencing difficulty in an educational setting.

2. Historical Overview

In ancient times the great Greek orators were known for giving long speeches that sometimes lasted more than two or three hours. They managed this task through the use of mnemonic, or memory devices that helped them to remember both the ideas and the order of the ideas for their presentations. The most famous of these techniques is the Method of Loci. Basically, using the Method of Loci involves remembering a series of locations in order. This could be the buildings and landmarks the orator passed on the way to the arena or the rooms in a large villa. As the ideas were generated for the speech, the orator would ‘store’ an image of the idea at a specific location. When the time came to give the speech, the ideas would be recalled as the speaker ‘went’ from location to location.

For years the study of mnemonics lay dormant until interest renewed in the second half of the twentieth century. Psychology has gone through major upheavals in the twentieth century. The rejection of philosophy and introspection as primary tools for the study of psychology led to the rise of behaviorism and the rejection of ‘mental’ phenomena. In the rush to be scientific in developing theories and methods, researchers lost their focus on the mind and cognitive processes. It was not until the late 1960s and the 1970s that studies of perception, memory, and cognitive processes once again gained prominence. Some of the earliest studies of memory re-examined the classical mnemonic systems in an attempt to identify and understand the cognitive processes involved in creating and using them. In the 1970s this literature was enriched by the work of Flavell and others on what he called ‘metacognition’ (Flavell 1971). Metacognition refers to thinking about thinking. It focuses on knowledge, reflection, and analyses of how an individual thinks and learns. Building on both of these themes, researchers increasingly turned their attention to cognition, the variables that impact cognition, and the degree to which cognition can be influenced through educational interventions. This is the research that led most directly to the study of learning to learn.

3. Types Of Learning To Learn Strategies

Weinstein and Mayer (1986) summarized much of the research and findings in ‘learning to learn’ and developed a taxonomy to describe the six major categories of learning strategies. The following is a summary of the categories in the taxonomy.

3.1 Rehearsal Strategies For Basic Learning Tasks

Many instructional tasks require simple recall. The acquisition of basic knowledge, however, is often just a first step in the creation of a more extensive and integrated knowledge base in an area. An example of a task in this category is memorizing the order of the colors in the spectrum. A useful strategy for this type of learning might be to repeat, in sequential order, the names of the colors.

3.2 Rehearsal Strategies For Complex Learning Tasks

Learning tasks in this category are more demanding and tend to involve knowledge and skills extending beyond the superficial learning of lists or unrelated bits of information. Examples of strategies in this category would include highlighting class notes or copying key ideas from the class readings. Like the rehearsal strategies for simple tasks, these methods are often most appropriate in the early stages of building a knowledge base in an area.

3.3 Elaboration Strategies For Basic Learning Tasks

Meaningful learning often involves building bridges between what is already known and what a student is trying to learn. Elaboration strategies help the student build these bridges by using previous knowledge or experiences to add to what he or she is trying to learn as a way to make the new information more meaningful and memorable. Examples of strategies in this area include generating a mental image of a scene described in a novel and relating a scientific principle to everyday experience. The facilitating effect of using these strategies is usually attributed to both the processing that is involved in creating the elaboration and the product itself.

3.4 Elaboration Strategies For Complex Learning Tasks

Strategies in this category help the learner to be more active in building bridges between prior knowledge or experience and more complex tasks. Examples of strategies in this category include paraphrasing and summarizing, applying a problem-solving strategy to a new problem, creating analogies, and using everyday experience to help understand a new concept.

3.5 Organization Strategies For Basic Learning Tasks

Organization strategies involve translating or transforming information into another form and creating some sort of scheme to provide structure for this new way of characterizing the information. Examples of organization strategies for basic tasks include grouping foreign language vocabulary words by their parts of speech and grouping the battles of World War II by their geographic location. Like elaboration strategies, the facilitating effect of organization strategies is usually attributed to both the processing that is involved in creating the organization and the product itself.

3.6 Organization Strategies For Complex Learning Tasks

Complex tasks can often be made more meaningful and more manageable by using organization strategies. Examples of strategies in this category include creating a hierarchy of main ideas to use in writing a term paper, generating a force diagram in physics, or creating an outline for the class notes from a section of a course. Like all of the strategies in the elaboration and organization categories, it is both the process and the outcome that appear to help in both knowledge acquisition and later recall and performance.

4. Model Of Strategic Learning

As research in ‘learning to learn’ expanded in the 1980s and 1990s, it became clear that a number of different factors contribute to, and influence both choice and type of strategy used by a student. For example, it is not enough for a student to know about different types of learning strategies. He or she must also know how to use them and under what conditions it is appropriate to use them. Another factor that affects the strategies selected and used by a student is the social contexts of both the educational setting, in general, and the individual classroom. There are also support variables that affect a student’s attitudes and beliefs about learning and his or her motivation to succeed. These variables help to generate a context in which effective learning can take place. For example, a student must be clear about his or her long-term and short-term academic goals in order to use them to aid his or her motivation to initiate and maintain use of effective learning strategies.

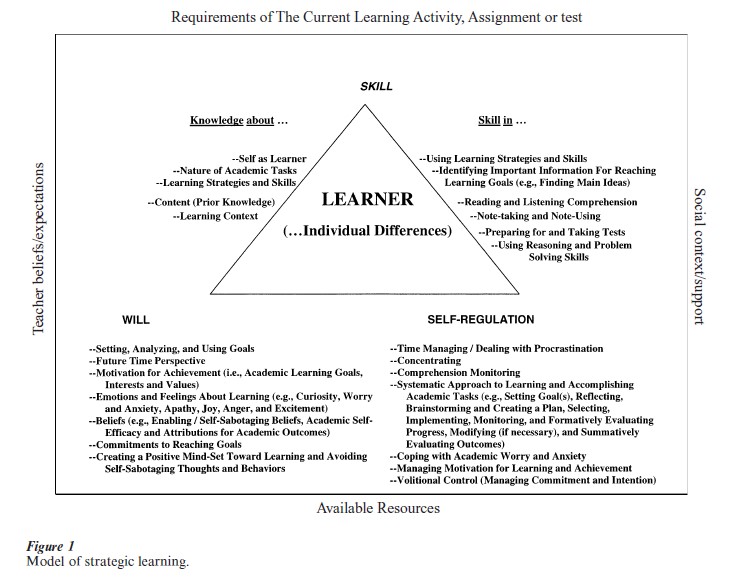

In the past researchers and educational program developers have usually focused on one or a subset of topics within learning to learn, such as cognitive elaboration strategies or student motivation. Current work is purposefully examining the interaction among two or more components related to the acquisition and use of learning strategies. This change is a result of the increasing understanding of the nature of student learning and school achievement at all educational levels. Researchers have found that it is the interaction among varying factors that results in successful learning and transfer of new knowledge and skills. The components that seem to have the greatest impact on a student’s acquisition and use of learning strategies are summarized in a model developed by Weinstein and her colleagues at the Cognitive Learning Strategies Project located at the University of Texas at Austin in the USA (see Fig. 1).

This model is an extension of the earlier model developed by Weinstein and Mayer (1986). It focuses on variables impacting strategic learning; learning that is goal driven. Briefly, the core of the model is the learner’s long-term learning goals and self-system variables. Goals are considered to be critical components that provide direction for self-regulating thoughts and actions and for generating and sustaining the motivation necessary to carry out those thoughts and behaviors. A hallmark of a strategic learner is that he or she sets specific and challenging, yet realistic, learning goals and actively pursues them. These learning goals are outcomes to be achieved in and of themselves, but are also subsumed within larger and much longer-term goals and thereby have a future utility value. However, setting specific learning goals is necessary but not sufficient to ensure successful learning outcomes. A strategic learner must also have the skills, motivation and self-regulatory thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors necessary to successfully pursue such goals. The core of the model is surrounded by these three components: (a) the learner’s ‘skill’ levels in relation to the learning task at hand; (b) the learner’s ‘will’ or motivation to accomplish the desired outcome; and (c) the learner’s ‘self-regulating thoughts, beliefs, and actions’ (sometimes referred to as executive control processes in earlier literature). It is the properties that emerge from the interactions among the learner and these components that are at the core of ‘learning to learn.’ For any given learning task, the student must take into account variables from each of these components.

5. Current Research, Methodological Issues, And Directions For Future Research

Much of the current research in learning to learn has focused on improving student learning outcomes, primarily in college or tertiary settings. Researchers have demonstrated the effectiveness of teaching learning to learn strategies to students, often with quite dramatic results. These results have also been robust across content domains, individual classes, and years of college.

Given the importance of learning to learn for student achievement and retention to graduation, additional research is needed to address some of the methodological and conceptual issues in this area. First, there is a need for the development of consistent terms for the various aspects of learning to learn. Currently, each individual or group of researchers uses somewhat different terms to often describe very similar ideas and processes. Second, there is a need for the further development of models of learning to learn at the global level and at more task-specific levels. Third, more knowledge is needed about the nature of transfer of ‘learning to learn’ strategies. Fourth, measurement of ‘learning to learn’ strategies and processes needs to be refined. Current instruments like the ‘Learning and Study Strategies Questionnaire’ and the ‘Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire’ are good general diagnostic screening measures, but more precise measurements of the components of ‘learning to learn’ and how they interact in a given learning context are needed. Fifth, additional developmental work to create instructional paradigms to teach learning to learn in both traditional learning contexts and web-based applications is needed.

‘Learning to learn’ is crucial for success in any learning context. As society moves toward a world where lifelong learning is a fundamental reality, the importance of understanding and using learning to learn strategies will only increase.

Bibliography:

- Boekaerts M, Pintrich P, Zeidner M (eds.) 2000 Handbook of Self-Regulation. Academic Press, New York, NY

- Flavell J H 1971 First discussant’s comments: What is memory development the development of? Human Development 14: 272–8

- Schunk D H, Zimmerman B J (eds.) 1998 Self-Regulated Learning: From Teaching to Self-Reflective Practice. Guilford, New York

- Weinstein C E, Hume L M 1988 Learning and Study Strategies. Academic Press, San Diego

- Weinstein C E, Mayer R E 1986 The teaching of learning strategies. In: Wittrock M C (ed.) Handbook of Research on Teaching, 3rd edn. Macmillan, New York, pp. 315–27