Sample Mastery Learning Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. The Theory and Practice of Mastery Learning

Since the 1970s, few programs have been implemented as broadly or evaluated as thoroughly as those associated with mastery learning. Programs based on mastery learning operate in the twenty-first century at every level of education in nations throughout the world. When compared to traditionally taught classes, students in mastery-learning classes have been consistently shown to learn better, reach higher levels of achievement, and to develop greater confidence in their ability to learn and in themselves as learners (Guskey and Pigott 1988, Kulik et al. 1990a).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

In this section we will describe how mastery learning originated and the essential elements involved in its implementation. We will then discuss the improvements in student learning that typically result from the use of mastery learning and how this strategy provides practical solutions to a variety of pressing instructional problems.

2. The Development of Mastery Learning

Although the basic tenets of mastery learning can be traced to such early educators as Comenius, Pestalozzi, and Herbart, most modern applications stem from the writings of Benjamin S. Bloom of the University of Chicago. In the mid-1960s, Bloom began a series of investigations on how the most powerful aspects of tutoring and individualized instruction might be adapted to improve student learning in group-based classes. He recognized that while students vary widely in their learning rates, virtually all learn well when provided with the necessary time and appropriate learning conditions. If teachers could provide these more appropriate conditions, Bloom (1968) believed that nearly all students could reach a high level of achievement.

To determine how this might be practically achieved, Bloom first considered how teaching and learning take place in typical group-based classroom settings. He observed that most teachers begin by dividing the material that they want students to learn into smaller learning units. These units are usually sequentially ordered and often correspond to the chapters in the textbook used in teaching. Following instruction on the unit, teachers administer a test to determine how well students have learned the unit material. Based on the test results, students are sorted, ranked, and assigned grades. The test signifies the end of the unit to students and the end of the time they need to spend working on the unit material. It also represents their one and only chance to demonstrate what they have learned.

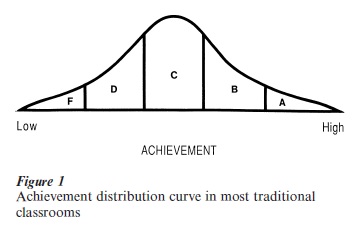

When teaching and learning proceed in this manner, Bloom found that only a small number of students (about 20 percent) learn the concepts and material from the unit well. Under these conditions, the distribution of achievement at the end of the instructional sequence looks much like a normal bellshaped curve, as shown in Fig. 1.

Seeking a strategy that would produce better results, Bloom drew upon two sources of information. He considered first the ideal teaching and learning situation in which an excellent tutor is paired with an individual student. In other words, Bloom tried to determine what critical elements in one-to-one tutoring might be transferred to group-based instructional settings. Second, he reviewed descriptions of the learning strategies used by academically successful students. Here Bloom sought to identify the activities of high achieving students in group-based learning environments that distinguish them from their less successful counterparts.

Bloom saw organizing the concepts and material to be learned into small learning units, and checking on students’ learning at the end of each unit, as useful instructional techniques. He believed, however, that the unit tests most teachers used did little more than show for whom the initial instruction was or was not appropriate. On the other hand, if these checks on learning were accompanied by a ‘feedback and corrective’ procedure, they could serve as valuable learning tools. That is, instead of marking the end of the unit, Bloom recommended these tests be used to ‘diagnose’ individual learning difficulties (feedback) and to ‘prescribe’ specific remediation procedures (correctives).

This feedback and corrective procedure is precisely what takes place when a student works with an excellent tutor. If the student makes an mistake, the tutor points out the error (feedback), and then follows up with further explanation and clarification (corrective). Similarly, academically successful students typically follow up the mistakes they make on quizzes and tests, seeking further information and greater understanding so that their errors are not repeated.

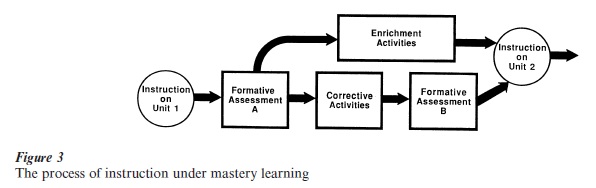

With this in mind, Bloom outlined an instructional strategy to make use of this feedback and corrective procedure. He labeled the strategy ‘Learning For Mastery’ (Bloom 1968), and later shortened it to simply ‘Mastery Learning.’ By this strategy, the important concepts students are to learn are first organized into instructional units, each taking about a week or two of instructional time. Following initial instruction on the unit concepts, a quiz or assessment is administered. Instead of signifying the end of the unit, however, this assessment is primarily used to give students information, or feedback, on their learning. To emphasize this new purpose Bloom suggested calling it a ‘formative assessment,’ meaning ‘to inform or provide information.’ A formative assessment precisely identifies for students what they have learned well to that point, and what they need to learn better. Included with the formative assessment are explicit suggestions to students on what they should do to correct their learning difficulties. These suggested corrective activities are specific to each item or set of prompts within the assessment so that students can work on those particular concepts they have not yet mastered. In other words, the correctives are ‘individualized.’ They might point out additional sources of information on a particular concept, such as the page numbers in the course textbook or workbook where the concept is discussed. They might identify alternative learning resources such as different textbooks, alternative materials, or computerized instructional lessons. Or they might simply suggest sources of additional practice, such as study guides, independent or guided practice exercises, or collaborative group activities. With the feedback and corrective information gained from a formative assessment, each student has a detailed prescription of what more needs to be done to master the concepts or desired learning outcomes from the unit.

When students complete their corrective activities, usually after a class period or two, they are administered a second, parallel formative assessment. This second assessment serves two important purposes. First, it verifies whether or not the correctives were successful in helping students remedy their individual learning problems. Second and more importantly, it offers students a second chance at success and, hence, serves as a powerful motivation device.

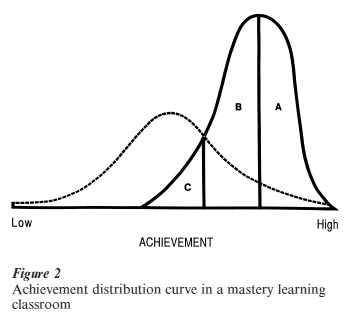

Bloom believed that by providing students with these more favorable learning conditions, nearly all could excellently learn and truly master the subject (Bloom 1976). As a result, the distribution of achievement among students would look more like that illustrated in Fig. 2. Note that the grading standards have not changed. Although the same level of achievement is used to assign grades, about 80 percent of the students reach the same high level of achievement under mastery-learning conditions that only about 20 percent do under more traditional approaches to instruction.

3. The Essential Elements of Mastery Learning

Since Bloom first outlined his ideas, a great deal has been written about the theory of mastery learning and its accompanying instructional strategies (e.g., Block 1971, 1974, Block and Anderson 1975). Still, programs labeled ‘mastery learning’ are known to greatly vary from setting to setting. As a result, educators interested in applying mastery learning have found it difficult to get a concise description of the essential elements of the process and the specific changes required for implementation.

In recent years two elements have been described as essential to mastery learning (Guskey 1997a). Although the appearance of these elements may vary, they serve a very specific purpose in a mastery learning classroom and clearly differentiate mastery learning from other instructional strategies. These two essential elements are (a) the feedback, corrective, and enrichment process; and (2) congruence among instructional components or alignment.

4. Feedback, Correctives, and Enrichment

To use mastery learning a teacher must offer students regular and specific information on their learning progress. Furthermore, that information or ‘feedback’ must be both diagnostic and prescriptive. That is, it should: (a) precisely reinforce what was important to learn in each unit of instruction; (b) identify what was learned well; and (c) describe what students need to spend more time learning. Effective feedback is also appropriate for students’ level of learning.

However, feedback alone will not help students greatly improve their learning. Significant improvement requires that the feedback be paired with specific corrective activities that offer students guidance and direction on how they can remedy their learning problems. It also requires that these activities be qualitatively different from the initial instruction. Simply having students go back and repeat a process that has already proven unsuccessful is unlikely to yield any better results. Therefore, correctives must offer an instructional alternative. They must present the material differently and involve students differently than did the initial teaching. They should incorporate different learning styles or learning modalities. Correctives also should be effective in improving performance. A new or alternative approach that does not help students overcome their learning difficulties is inappropriate as a corrective approach and should be avoided.

In most group-based applications of mastery learning, correctives are accompanied by enrichment or extension activities for students who master the unit concepts from the initial teaching. Enrichment activities provide these students with exciting opportunities to broaden and expand their learning. The best enrichments are both rewarding and challenging. Although they are usually related to the subject area, enrichments need not be tied directly to the content of a particular unit. They offer an excellent means of involving students in challenging, higher level activities like those typically designed for the gifted and talented.

This feedback, corrective, and enrichment process, illustrated in Fig. 3, can be implemented in a variety of ways. Many mastery learning teachers use short, paper-and-pencil quizzes as formative assessments to give students feedback on their learning progress. But a formative assessment can be any device used to gain evidence on students’ learning progress. Thus, essays, compositions, projects, reports, performance tasks, skill demonstrations, and oral presentations can all serve as formative assessments.

Following a formative assessment, some teachers divide the class into separate corrective and enrichment groups. While the teacher directs the activities of students involved in correctives, the others work on self-selected, independent enrichment activities that provide opportunities for these students to extend and broaden their learning. Other teachers team with colleagues so that while one teacher oversees corrective activities the other monitors enrichments. Still other teachers use cooperative learning activities in which students work together in teams to ensure all reach the mastery level. If all attain mastery on the second formative assessment, the entire team receives special awards or credit.

Feedback, corrective, and enrichment procedures are crucial to the mastery learning process, for it is through these procedures that mastery learning ‘individualizes’ instruction. In every unit taught, students who need extended time and opportunity to remedy learning problems are offered these through correctives. Those students who learn quickly and for whom the initial instruction was highly appropriate are provided with opportunities to extend their learning through enrichment. As a result, all students are provided with favorable learning conditions and more appropriate, higher quality instruction.

5. Congruence Among Instructional Components

While feedback, correctives, and enrichment are extremely important, they alone do not constitute mastery learning. To be truly effective, they must be combined with the second essential element of mastery learning: congruence among instructional components.

The teaching and learning process is generally perceived to have three major components. To begin we must have some idea about what we want students to learn and be able to do; that is, the learning goals or outcomes. This is followed by instruction that, hopefully, results in competent learners—students who have learned well and whose competence can be assessed through some form of evaluation. Mastery learning adds a feedback and corrective component that allows teachers to determine for whom the initial instruction was appropriate and for whom learning alternatives are required.

Although essentially neutral with regard to what is taught, how it is taught, and how the result is evaluated, mastery learning does demand there be consistency and alignment among these instructional components. For example, if students are expected to learn higher level skills such as those involved in application or analysis, mastery learning stipulates that instructional activities be planned to give students opportunities to actively engage in those skills. It also requires that students be given specific feedback on their learning of those skills, coupled with directions on how to correct any learning errors. Finally, procedures for evaluating students’ learning should reflect those skills as well.

Ensuring congruence among instructional components requires teachers to make some crucial decisions. They must decide, for example, what concepts or skills are most important for students to learn and most central to students’ understanding of the subject. But in essence, teachers at all levels make these decisions daily. Every time a test is administered, a paper is graded, or any evaluation made, teachers communicate to their students what they consider to be most important. Using mastery learning simply compels teachers to make these decisions more thoughtfully and more intentionally than is typical.

6. Misinterpretations of Mastery Learning

Some early attempts to implement mastery learning were based on narrow and inaccurate interpretations of Bloom’s ideas. These programs focused on low level cognitive skills, attempted to break learning down into small segments, and insisted students ‘master’ each segment before being permitted to move on. Teachers were regarded in these programs as little more than managers of materials and record-keepers of student progress. Unfortunately, similar misinterpretations of mastery learning continue in the twenty-first century. Nowhere in Bloom’s writing can the suggestion of such narrowness and rigidity be found. Bloom considered thoughtful and reflective teachers vital to the successful implementation of mastery learning and stressed flexibility in his earliest descriptions of the process:

There are many alternative strategies for mastery learning. Each strategy must find some way of dealing with individual differences in learners through some means of relating the instruction to the needs and characteristics of the learners. The nongraded school is one attempt to provide an organizational structure that permits and encourages mastery learning (Bloom 1968, pp. 7–8).

Bloom also emphasized the need to focus instruction in mastery learning classrooms on higher level learning outcomes, not simply basic skills. He noted:

I find great emphasis on problem solving, applications of principles, analytical skills, and creativity. Such higher mental processes are emphasized because this type of learning enables the individual to relate his or her learning to the many problems he or she encounters in day-to-day living. These abilities are stressed because they are retained and utilized long after the individual has forgotten the detailed specifics of the subject matter taught in the schools. These abilities are regarded as one set of essential characteristics needed to continue learning and to cope with a rapidly changing world (Bloom 1978, p. 578).

Recent research studies in fact show that mastery learning is highly effective when instruction focuses on high level outcomes such as problem solving, drawing inferences, deductive reasoning, and creative expression (Guskey 1997a).

7. Research Results and Implications

Implementing mastery learning does not require drastic alterations in most teachers’ instructional procedures. Rather, it builds on the practices teachers have developed and refined over the years. Most excellent teachers are undoubtedly using some form of mastery learning already. Others are likely to find the process blends well with their present teaching strategies. This makes mastery learning particularly attractive to teachers, especially considering the difficulties associated with new approaches that require major changes in teaching.

Despite the relatively modest changes required to implement mastery learning, extensive research evidence shows the use of its essential elements can have very positive effects on student learning (Guskey and Pigott 1988, Kulik et al. 1990a). Providing feedback, correctives, and enrichments; and ensuring congruence among instructional components; takes relatively little time or effort, especially if tasks are shared among teaching colleagues. Still, evidence gathered in the USA, Asia, Australia, Europe, and South America shows the careful and systematic use of these elements can lead to significant improvements in student learning.

Equally important, the positive effects of mastery learning are not only restricted to measures of student achievement. The process has also been shown to yield improvements in students’ school attendance rates, their involvement in class lessons, and their attitudes toward learning (Guskey and Pigott 1988). This multidimensional impact has been referred to as the ‘multiplier effect’ of mastery learning, and makes it one of today’s most cost-effective means of educational improvement.

It should be noted that one review of the research on mastery learning, contrary to all previous reviews, indicated that the process had essentially no effect on student achievement (Slavin 1987). This finding not only surprised scholars familiar with the vast research literature on mastery learning showing it to yield very positive results, but also large numbers of practitioners who had experienced its positive impact first hand. A close inspection of this review shows, however, that it was conducted using techniques of questionable validity, employed capricious selection criteria (Kulik et al. 1990b), reported results in a biased manner, and drew conclusions not substantiated by the evidence presented (Guskey 1987). Most importantly, two much more extensive and methodologically sound reviews published since (Guskey and Pigott 1988, Kulik et al. 1990a) have verified mastery learning’s consistently positive impact on a broad range of student learning outcomes and, in one case (i.e., Kulik et al. 1990b), clearly showed the distorted nature of this earlier report.

8. Conclusion

Researchers in 2001 generally recognize the value of the essential elements of mastery learning and the importance of these elements in effective teaching at any level. As a result, fewer studies are being conducted on the mastery learning process, per se. Instead, researchers are looking for ways to enhance results further, adding to the mastery learning process additional elements that positively contribute to student learning in hopes of attaining even more impressive gains (Bloom 1984). Recent work on the integration of mastery learning with other innovative strategies appears especially promising (Guskey 1997b).

Mastery learning is not an educational panacea and will not solve all the complex problems facing educators today. It also does not reach the limits of what is possible in terms of the potential for teaching and learning. Exciting work is continuing on new ideas designed to attain results far more positive than those typically derived through the use of mastery learning (Bloom 1984, 1988). Careful attention to the essential elements of mastery learning, however, will allow educators at all levels to make great strides toward the goal of all children learning excellently.

Bibliography:

- Block J H (ed.) 1971 Mastery Learning: Theory and practice. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York

- Block J H (ed.) 1974 Schools, Society and Mastery Learning. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York

- Block J H, Anderson L W 1975 Mastery Learning in Classroom Instruction. Macmillan, New York

- Bloom B S 1968 Learning for mastery. E aluation Comment 1(2): 1–12

- Bloom B S 1976 Human Characteristics and School Learning. McGraw-Hill, New York

- Bloom B S 1978 New views of the learner: implications for instruction and curriculum. Educational Leadership 35(7): 563–76

- Bloom B S 1984 The two-sigma problem: the search for methods of group instruction as effective as one-to-one tutoring. Educational Researcher 13(6): 4–16

- Bloom B S 1988 Helping all children learn in elementary school and beyond. Principal 67(4): 12–17

- Guskey T R 1987 Rethinking mastery learning reconsidered. Re iew of Educational Research 57: 225–9

- Guskey T R 1997a Implementing Mastery Learning, 2nd edn. Wadsworth, Belmont, CA

- Guskey T R 1997b Putting it all together: integrating educational innovations. In: Caldwell S J (ed.) Professional Development in Learning-Centered Schools. National Staff Development Council, Oxford, OH, pp. 130–49

- Guskey T R, Pigott T D 1988 Research on group-based mastery learning programs: a meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Research 81: 197–216

- Kulik C C, Kulik J A, Bangert-Drowns R L 1990a Effectiveness of mastery learning programs: a meta-analysis. Re iew of Educational Research 60: 265–99

- Kulik J A, Kulik C C, Bangert-Drowns R L 1990b Is there better evidence on mastery learning? A response to Slavin. Re iew of Educational Research 60: 303–7

- Slavin R E 1987 Mastery learning reconsidered. Re iew of Educational Research 57: 175–213