Sample Historical Perspectives on Education And Gender Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Formal systems of education in the modern world have a two-way relationship with societal gender inequality: they reflect prevailing ideologies about gender roles and, under some circumstances, have ameliorated gender inequality in the larger society. This research paper traces major historical changes in gender inequality in education, primarily focusing on the United States from the period immediately prior to the creation of formal state-supported systems of schooling to the present. Changes in gender inequality in access to education have been dramatic: once largely denied formal schooling, in many parts of the world girls now have equal or better access to secondary and, sometimes even, higher education than boys. Former gender differences in curricular opportunities have been narrowed significantly, especially in the West, and gender bias in texts, social interaction, and school-based activities has been dramatically reduced as well. Gender inequalities and bias in education are institutionalized more deeply in parts of the world where women still are restricted largely to the private sphere.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Access

1.1 Education Before State-Supported Systems

The story of gender and education in the West has to start in the years before formal state-supported systems of education were common. In the seventeenth-and eighteenth-century United States, for example, schooling was provided through a patchwork of arrangements and formal schooling opportunities were largely closed to girls. Some girls did receive instruction in town and private schools: girls who were ‘smuggled in’ after the boys had gone home for the day (Tyack and Hansot 1990, Sadker and Sadker 1994). Early ‘dame schools’—schools privately subsidized by parents—did admit girls, and it was from the dame schools that public school systems later evolved. The exclusion of girls from early formal schooling in the United States reflected the prevailing ideology that women were destined for domesticity; public life was reserved for males.

1.2 Early State-Supported Education

State-supported systems of education emerged in the United States by the first third of the nineteenth century (the last third of the century in the American South). One distinctive feature of American state supported schooling, or ‘common schooling,’ as it was known, is that it was coeducational. Boys and girls were educated together in the same school buildings—often one-room schools in rural areas providing what we would today regard as an elementary education (Tyack and Hansot 1990). The early institutionalization of coeducation put limits on the forms that gender inequality in education could take and gave girls roughly the same access to schooling as boys. Coeducation was preferred in the American case mostly because of the economies of scale it allowed rather than from an ideological commitment to educating boys and girls side-by-side. Single-sex school buildings were more common in Western Europe and Britain during this formative period of state-supported schooling in the nineteenth century, and the United States remained somewhat distinctive by allowing girls similar overall access to state-supported schools.

1.3 School Expansion, Access, And Attainment

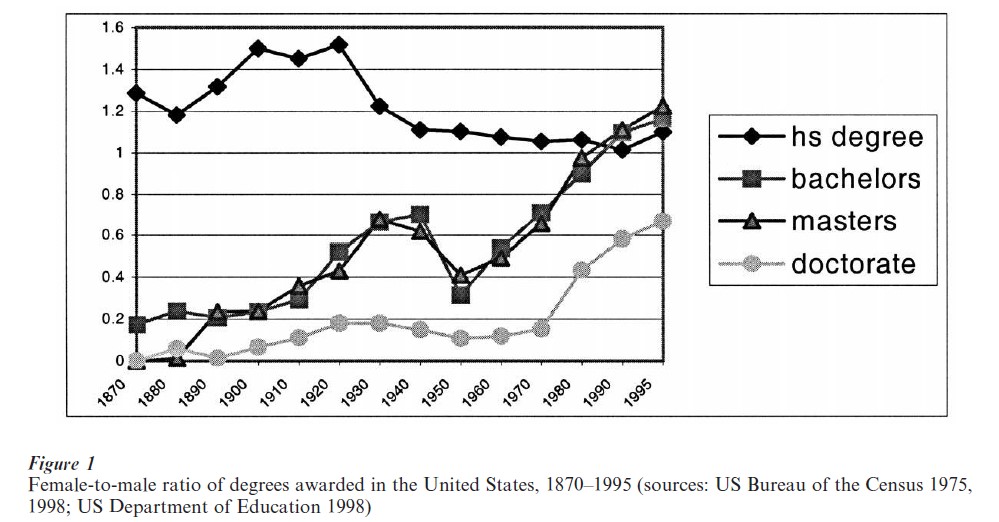

Cities and townships started to establish secondary schools around the mid-nineteenth century, although secondary schools enrolled only a tiny fraction of eligible youth before the early twentieth century. From the outset of the establishment of secondary schools, girls actually outnumbered boys. The federal government started to keep statistics on the number of high school graduates in 1870; in that year there were 7,000 male graduates compared to 9,000 female graduates (US Bureau of the Census 1975). From the nineteenth century to the present, American women have maintained their advantage over men with respect to likelihood of high school graduation (see Fig. 1; a ratio greater than one indicates a female advantage).

Gender distinctions were embedded more institutionally in nineteenth-century higher education than in elementary and secondary education, perhaps because a large proportion of colleges and universities were private and higher education remained the province of the elite until after World War II. Nineteenth-century American women had many fewer opportunities to attend college than their male peers had; Oberlin became the first American college to admit women but it was one of the only university options American women had until after the Civil War (Sadker and Sadker 1994). The gender inequality in access to higher education was reflected in stark gender differences in degrees obtained: in 1870, male bachelor’s recipients outnumbered female recipients by almost 6 to 1. The gap closed gradually; by 1920, the male advantage in bachelor’s degrees conferred was slightly less than 2 to 1 and in 1982 women surpassed men in the number of bachelor’s degrees conferred for the first time—an advantage that has continued to widen (see Fig.1). From 1890 on, trends in gender inequality in receipt of masters degrees basically mirrored the trends in baccalaureates. Inequalities at the doctoral level, however, took much longer to close to any significant degree and at this level the male advantage is still significant: in 1995, men were 1.5 times more likely to get doctoral degrees than women.

1.4 The United States In Comparative Perspective

The relatively early timing of rough gender parity, or even female advantage, in access to secondary and baccalaureate-level education in the United States is unusual, as is the relatively early expansion of secondary and higher education to non-elites, and there are some countries in which women still experience significant disadvantages in access to education. In Britain and other English-speaking democracies, most of Europe, and most of Latin America, gender parity at the secondary and baccalaureate levels was achieved far more recently than in the United States. Although gender inequality in access to education has declined over time from its once substantial levels in most Asian countries, including the rich countries of Japan and Korea, gender inequality remains greater there than in any European state. Finally, large differences in women’s and men’s access to education still exist in much of Africa and the Middle East, with Muslim countries exhibiting the most gender inequality in access (Brint 1998, Stromquist 1995). The overall pattern is that societies in which women have been most fully incorporated into the public sphere exhibit the greatest gender equality in access to education.

2. Gender, Curriculum, And Social Climate

Being in the same schoolhouse, or even the same room, with boys did not and still does not mean that girls received the same education as boys. Unlike access, in the case of curriculum and social climate the picture is not one of increasingly similar experiences for boys and girls; looking back at the last 200 years, gender inequality increased before it decreased.

2.1 The Nineteenth Century And ‘Identical Coeducation’

By the mid-nineteenth century, when the common school was established firmly in American society, the available evidence suggests that boys and girls were by and large exposed to the same kind of curricular materials and were expected to gain similar things from schooling: basic literacy and numeracy, and appropriate political and moral values (Clifford 1982). By 1850, the relatively sizable male advantage in literacy that had existed at the time of the Revolution largely had been erased. Americans’ reasons for supporting basic literacy and numeracy differed by gender: for boys for their future roles in the public sphere and for girls for their future roles as mothers of the republic (Tyack and Hansot 1990). One possible reason why a ‘common’ education generally was provided to boys and girls throughout the nineteenth century is that the ideology and practice of separate spheres was established so firmly in American society that educating boys and girls together for purposes of basic literacy and numeracy hardly challenged it. And the adult social roles depicted in their curricular materials, particularly the ubiquitous McGuffey Readers, clearly reflected a world of separate spheres (Tyack and Hansot 1990). Further, it is likely that noninstructional activities, such as chores, were rigidly differentiated by gender.

2.2 The Progressive Era And Gender Differentiation

Throughout the late nineteenth century, attendance rates at the high-school level were low and the curriculum was almost entirely academic. High schools in some cities were single-sex, but as was the case for common schools the most frequent pattern was to have coeducational high schools. Available data suggest that girls and boys took quite similar courses (Latimer 1958). All that changed with the rapid expansion of the high school in the early twentieth century and its corresponding transformation from a primarily academic, or classical, curriculum to a vocational curriculum. Vocational education was proposed as a means to prepare students for adult life; in the case of gender, it meant preparing boys and girls for starkly different expected adult social roles. Progressive-era educational reformers increasingly called for differentiated education for boys and girls (Cremin 1961).

Instruction in the core academic subjects remained largely coeducational. But the core academic subjects occupied a decreasing portion of most students’ time as the twentieth century unfolded. Gender-differentiated vocational education became much better established in public high schools. The new curriculum in home economics, for example, was targeted to girls. Industrial education, especially those courses providing ‘manual training,’ was almost entirely for boys. Girls were the ones who flocked to new courses in commercial education. And boys became more likely to take advanced elective academic courses, especially in math and science (Tyack and Hansot 1990, Clifford 1982). Further, physical education and the increasingly diverse opportunities for extracurricular activities, including sports, were differentiated by gender sharply. These transformations set the institutionalized gender parameters of American education until the 1970s, when the more extreme forms of gender differentiation lost their social legitimacy.

2.3 The ‘Discovery’ Of Sexism In Schools

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, social science scholarship began to take a critical look at education and social inequality; this early work, however, focused primarily on class (see, e.g., Bowles and Gintis 1976). Gender bias in the formal knowledge conveyed by schools and in taken-for-granted social interactions in schools and classrooms was not ‘discovered’ until slightly later, when feminist scholars and activists turned their attention to classrooms, curriculum, and texts (for early examples, see Frazier and Sadker 1973, Stacey et al. 1974). The forms of gender bias and gendered social interactions identified in these works were not new social phenomena; what was new, however, was the definition of them as a social problem to be rectified. Note that the feminist critique of sexism in schools could not have been mounted successfully until a time, such as the 1970s, when a more general, society-wide ideology of equality between women and men was gaining legitimacy.

Early critics identified a number of ways in which American schools commonly exhibited bias against girls. As summarized by Tyack and Hansot (1990), the most important charges included: biased textbooks, favoritism of boys in classroom interactions, sex-typed counseling of students into courses and careers, a paucity of athletic opportunities for girls, the overrepresentation of males in high-level math and science courses, and male domination of educational administration. The cause of eliminating sex bias in schools got a boost in 1972 when the federal government passed Title IX of the 1972 Education Amendments, which prohibited sex discrimination in any educational program receiving federal funds. (In the United Kingdom, the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act similarly boosted the cause of gender equality in education (Arnot et al. 1999).) Title IX enforcement was slow and uneven, but the act itself, coupled with other antidiscrimination measures passed in the 1960s and 1970s, helped promote a social climate that made gender bias socially unacceptable and provided leverage for local activists and educators to implement change in schools. The major credit for the transformation in gender relations in schools, however, has to go to the rapid changes that took place in the family and the workplace.

It is difficult to evaluate the degree to which gender bias has been eliminated in the thousands of schools in a decentralized system such as that in the United States, but the most progress has probably been made with respect to biased textbooks, course and career counseling, and athletic opportunities. These forms of bias were institutionalized more formally and easier to change via centralized authority. A recent assessment of the schools’ progress toward elimination of gender bias reports that girls are no longer underrepresented in some forms of science (e.g., biology) but remain underrepresented in courses in advanced math, computer science, physics, and calculus; the gender gap in sports participation narrowed in the 1990s but girls are still much less likely to participate in a team sport; and boys are more at risk of dropping out or repeating a grade than girls (American Association of University Women 1999).

Gender differences in vocational preference testing was eliminated long ago, and schools have no doubt made much progress toward counseling similar boys and girls toward similar future plans (Tyack and Hansot 1990). Although more difficult to gauge, recent studies suggest that boys still get more attention from teachers and are more likely to be called on in class—forms of microinteraction that are not only difficult to change by policy decree but also are often unnoticed by those engaging in the practices (Sadker and Sadker 1994). In some important respects, however, the gender gap has been inverted. In the US and the UK, among other places, girls at the secondary level now outperform boys. In Britain, interestingly, this has caused not a public celebration over girls’ success but a moral panic over boys’ low achievement (Arnot et al. 1999).

3. Summary

Although in the West important gender differences in educationally-based opportunity structures remain, the institutionalized forms of gender bias that prevailed in the past have been greatly reduced. Nonetheless, those changes have not been sufficient to eliminate the significant gender differences in educational experiences or outcomes that are produced by daily microinteractions among students and between students and adults (Brint 1998). Further, some gender differentiation is the result of active choices made by boys and girls themselves that follow from gender socialization and, at the same time, are reinforced by the continuing sexism and gender differentiation common in other spheres of life, including the family and the workplace. Although at present significant forms of gender inequality and bias remain in schools, especially at the most selective levels, education is, at the same time, the most gender-neutral social institution in the contemporary Western world and in some important respects girls and women now outperform boys and men in selected Western countries. Educational gender inequality and bias remain more institutionalized in societies in which women are more restricted to the private sphere.

Bibliography:

- American Association of University Women 1999 Gender Gaps: Where Schools Still Fail Our Children. Marlowe, New York

- Arnot M, David M, Weiner G 1999 Closing the Gender Gap. Polity Press, Cambridge, UK

- Bowles S, Gintis H 1976 Schooling in Capitalist America. Basic Books, New York

- Brint S 1998 Schools and Societies. Pine Forge Press, Thousand Oaks, CA

- Clifford G J 1982 Marry, stitch, die, or do worse: Educating women for work. In: Kantor H, Tyack D B (eds.) Work, Youth, and Schooling: Historical Perspectives on Vocationalism in American Education. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

- Cremin L A 1961 The Transformation of the School: Progressivism in American Education – 1876–1957, 1st edn. Knopf, New York

- Frazier N, Sadker M 1973 Sexism in School and Society. Harper & Row, New York

- Latimer J F 1958 What’s Happened to Our High Schools? Public Affairs Press, Washington, DC

- Sadker M, Sadker D 1994 Failing at Fairness: How America’s Schools Cheat Girls. C. Scribner’s, New York

- Stacey J, Bereaud S, Daniels J (eds.) 1974 And Jill Came Tumbling After: Sexism in American Education. Dell Publishing, New York

- Stromquist N P 1995 Romancing the state: Gender and power in education. Comparative Education Review 39: 423–54

- Tyack D B, Hansot E 1990 Learning Together: A History of Coeducation in American Schools. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT

- US Bureau of the Census 1975 Historical Statistics of the United States – Colonial Times to 1970, Bicentennial edn. US Department of Commerce, Washington, DC

- US Bureau of the Census 1998 Statistical Abstract of the United States. US Department of Commerce, Washington, DC

- US Department of Education 1998 Digest of Educational Statistics. Department of Commerce, Washington, DC