Sample Cooperative Learning In Schools Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Cooperative learning, instructional methods in which students work in small groups to learn academic material, is one of the most extensively studied and widely used classroom innovations. Hundreds of studies have compared cooperative learning to other instructional methods on various social and academic measures. By far the most frequent objective of cooperative learning research has been to harness its effects on student achievement. Field and laboratory studies of the achievement effects of cooperative learning have been conducted in every major subject, at every grade level, and in all types of schools the world over. Cooperative learning is not only the subject of research and theory, the knowledge gene-rated by that labor is used at some level by hundreds of thousands of teachers. A national survey of US teachers found that 79 percent of elementary teachers and 62 percent of middle school teachers reported making some sustained use of cooperative learning (Puma et al. 1993).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

While there is little doubt about the facilitating effect of certain forms of cooperative learning on student achievement, there is still great disagreement over how and why cooperative learning affects achievement. Perhaps more importantly, there is intense debate over the conditions under which cooperative learning practices are effective. Some researchers describe theoretical mechanisms under-lying the achievement effects of cooperative learning that are completely different and at odds with those assumed or described by others. In particular, some scholars emphasize the role of incentive structure while others attribute achievement effects to students’ interactions in the types of task structures used in cooperative learning. Though often working in parallel, there has been remarkably little cross-fertilization in the work of cooperative learning researchers. Applications and investigations of cooperative learning emerging from different perspectives typically differ in their operationalization of aspects of both the incentive and task structures. As a result, it is difficult to determine which is responsible for which outcomes.

This research paper summarizes and updates earlier discussions of the major theoretical perspectives that seek to explain the facilitating effects of cooperative learning (Slavin 1995). It describes motivational, social cohesion, and cognitive elaboration perspectives on cooperative learning and explores the conditions under which each may operate. Finally, it suggests future research that will be needed to sustain the study and practice of cooperative learning in the twenty-first century.

1. Four Major Theoretical Perspectives On Cooperative Learning And Achievement

1.1 Motivational Perspectives

Motivational perspectives on cooperative learning emphasize the reward and/or goal structure of the learning environment (Slavin 1995). In order to achieve personal goals, each student must attend not only to his or her own efforts but to those of other group members as well. Cooperative incentive structures (e.g., group rewards based on the learning of all group members) encourage students to engage in behaviors that help the group achieve its goals. These behaviors include maintaining self-motivation, giving or withholding praise, sanctioning, assisting, and encouraging others. According to the motivational perspective, the beneficial effects of cooperative learning for achievement are primarily due to the incentive provided for students to encourage and help one another to learn.

The motivationalist critique of traditional class-room organization holds that competitive grading and the informal reward system common in classrooms creates and maintains negative goal interdependence among students. Since one student’s success lessens the opportunities others will have to succeed, students may hope for others’ failure. They are discouraged from supporting each other’s efforts. Such conflicts may ultimately lead to peer norms opposing academic achievement.

Motivational theorists build criterion-based group rewards into their cooperative learning methods. In strategies developed at Johns Hopkins University (Slavin 1995), students work to earn certificates and other recognition for their efforts if the average score of each team member exceeds a pre-established criterion (see also Kagan 1995). Methods developed by Johnson and Johnson (1994) and their colleagues often give grades based on group performance. The theoretical rationale for these group rewards is that if students are encouraged to value the success of the group, they will encourage and help one another to achieve. This mode of operation stands in contrast to the negative goal interdependence common in traditional competitive classrooms.

1.1.1 Empirical Support For The Motivationalist Perspective. There is a great deal of empirical support for the motivationalist assertion that group rewards are essential to the success of cooperative learning in classrooms, with one critical qualification. A number of studies have concluded that the use of group goals rewards enhances achievement only in cases where the group reward is based on the individual learning of each student in the group (Slavin 1995). Most often this means that team scores are derived from quizzes that the team members take individually, without help. When group rewards are given based on a single group product (i.e., without individual accountability), there is little incentive for students to cooperate and one or two group members may do all of the work. In student team-achievement divisions (STAD) (Slavin 1995), students work in mixed ability teams to master material initially presented by the teacher. After working in their teams, students take individual quizzes on the material. Teams can only succeed if they make sure that all team members have learned, so the work sessions focus on team members explaining concepts to one another.

A review of 99 cooperative learning studies that involved durations of at least four weeks compared achievement gains in cooperative learning and control groups. Of 64 studies of cooperative learning methods that provided group rewards based on the sum of group members’ individual learning, 50 (78 percent) found significant positive effects on achievement and none found negative effects (Slavin 1995). The median effect size for those studies for which effect sizes could be computed was +0.32. Studies which gave rewards based on a single group product, or which gave no rewards, found few positive effects, with a median effect size of only + 0.07. Studies which compared different modes of cooperative goal structure within the same study found similar patterns. Group goals with rewards based on individual learning were important to the instructional effectiveness of co-operative learning models.

1.2 Social Cohesion Perspective

According to Cohen (1994 pp. 69–70), ‘if the task is challenging and interesting, and if students are sufficiently prepared for skills in group process, students will experience the process of group work itself as highly rewarding … never grade or evaluate students on their individual contributions to the group or product.’ Cohen’s work may be described as social cohesion theories. They emphasize that the effects of cooperative learning on achievement are largely mediated by the cohesiveness of the group. As such, they downplay the role of incentives and accountability (Cohen 1994, Johnson and Johnson 1996). As such, their work often emphasizes team-building activities in preparation for cooperative learning and processing or group self-evaluation during and after group activities.

Cohen et al. (1992) all use forms of cooperative learning in which students take on individual roles within the group. A major purpose of these techniques is to create interdependence within the group and in the classroom. Slavin (1983) terms this ‘task specialization.’ In Aronson’s Jigsaw method (1978), students study material on one of several topics distributed among group members. They meet in expert groups to share information on their topics with members of other teams who have been assigned the same topic, and then take turns presenting their topic to their respective teams. In Sharan’s group investigation method, groups take on topics from a unit presented to the entire class and further subdivide them among members of the group. They then investigate their assigned topics as a group and ultimately present their findings to the class.

The social cohesion and motivational perspectives differ in that social cohesion theorists assume that students will work together because, and to the extent that, they care about each other, the group, and achievement. Motivational theorists, on the other hand, assume that students help their classmates at least in part because it serves their own interests to do so. Both perspectives focus primarily on motivational rather than cognitive explanations for the instructional effectiveness of cooperative learning. Both models treat motivation as the critical variable to be manipulated toward fostering achievement and both regard cooperation as a way to affect student motivation. The relationship (and tension) between the social cohesion and motivationalist perspectives is apparent in the work of Johnson and Johnson (1994). While their models do make use of group goals and group incentives such as recognition and grades, their own and related theoretical writings emphasize the development of group cohesiveness and social group processing strategies.

1.2.1 Empirical Support For The Social Cohesion Perspective. The achievement outcomes of cooperative learning methods that emphasize social and task variables are inconsistent. Concerning task specialization, there is evidence that, when well implemented, group investigation can significantly increase student achievement (e.g., Sharan and Sharan 1992). However, research on the original form of Jigsaw has not typically yielded positive effects on achievement, except in cases where group rewards have been added to the original model (Mattingly and Van Sickle 1991). In studies of at least four weeks’ duration, the Johnson and Johnson (1994) methods have not been found to increase achievement more than individualistic methods unless they incorporate group rewards (grades) based on the average of group members’ individual quiz scores (see Slavin 1995).

Research on the practical applications of methods based on social cohesion theories provide inconsistent support for the proposition that building cohesiveness among students through team-building without group reward incentives will enhance student achievement. Yager et al. (1986) found that group processing activities did enhance the achievement effects of cooperative learning. However, other investigations of the Jigsaw model have found that team building activities had no effect on achievement outcomes.

With the exception of the group investigation model, there is inconsistent evidence that social cohesion and group process forms of cooperative learning that do not include individual accountability are superior to traditional instruction. Further, group investigation methods include an evaluation based on group efforts that is composed of individual team member contributions. This may amount to a type of group reward with individual accountability, and may thus reconcile the findings with the assertions of motivationalist theory.

1.3 Cognitive Perspectives

The cognitive perspectives offer explanations for the beneficial effects of cooperative learning which are quite different from those presented thus far. Under the general heading of cognitive perspectives, these theories can be said to place the value of cooperative learning in the interactions among students during group work. These interactions are said to affect students’ mental processing of information to be learned rather than their motivation to learn the material. Within that general heading some work is focused on cognitive development, while other work concerns cognitive processes more generally.

Developmentalist theorists work under the fundamental assumption that children’s interactions around appropriate tasks increase their mastery of critical concepts. Vygotsky’s ‘zone of proximal development’ is the distance between the child’s actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving, and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers (Vygotsky 1978, p. 86). Collaborative activity among children promotes growth because children of similar ages are likely to function in each other’s zones of proximal development, modeling in the collaborative behaviors more advanced than each could perform as individuals.

Similarly, Piaget (1926) held that social-arbitrary knowledge—language, values, rules, morality, and symbol systems—can only be learned in interactions with others. Interaction is also essential to logical and mathematical thought development in disequilibrating a child’s conceptions and in providing feedback about the validity of logical constructions. For example, if a child has an incorrect conception, interaction with peers increases the chances that the child will move to a more sophisticated understanding. There is considerable support for the notion that peer interaction can help nonconservers become conservers, and for the importance of peers working in each other’s zones of proximal development.

On the basis of these and other findings, Piagetian and Vygotskian, theorists have prescribed increased use of cooperative activities in schools. Damon (1984) draws on these ideas in proposing a conceptual foundation for peer-based learning which explicitly rejects the use of extrinsic incentives. Nonetheless, despite wide theoretical and laboratory support for the cognitive models of cooperative learning, there is as yet little evidence from classroom experiments done for meaningful intervals that ‘pure’ cooperative methods, without group rewards and individual account-ability, produce higher achievement. Still, it seems likely that the cognitive processes described by developmental theorists underlie the effectiveness of cooperative learning in any form; motivation to help or encourage others is likely to increase the quantity or quality of peer interactions, which in turn lead to cognitive growth.

1.4 Cognitive Elaboration Perspective

Research in cognitive psychology has long held that that if information is to be retained and integrated in memory, the learner must engage in some sort of cognitive restructuring or elaboration of the material. It is also widely accepted that one of the more effective means of elaboration is explaining the material to another. Noreen Webb (1989) found that the students who gained the most from cooperative activities were those who gave elaborated explanations to others. This contention also is supported in empirical work concerning peer tutoring, and cooperative scripts. Classroom investigations have yielded similar findings in writing instruction and in reciprocal teaching for reading comprehension.

2. Reconciling The Perspectives

The perspectives discussed above are typically debated in the theoretical and empirical literature as if they were contradictory. They arise out of deeply differing metatheoretical orientations, each with well-established theoretical bases and sufficient supporting evidence to assure that they apply in some circumstances. By the same token, their variety assures that none of them is both necessary and sufficient in every setting. The debate is complicated because research in each tradition tends to establish settings and conditions that favor that perspective. For example, most co-operative learning research from the motivationalist and social cohesion perspectives is conducted in class-rooms where students may be accustomed to working for extrinsic rewards, and over extended time periods since social cohesion may be expected to take time to develop.

In contrast, studies from developmental and cognitive elaboration views tend to be brief, making issues of motivation moot. These latter paradigms also tend to use pairs, rather than groups of three or more; pairs may involve more simple interaction dynamics and require less time to develop modes of working together. Developmental research almost exclusively uses young children and traditional Piagetian tasks which bear little resemblance to the social-arbitrary learning that characterizes most classroom learning. Cognitive elaboration research mostly involves college student samples.

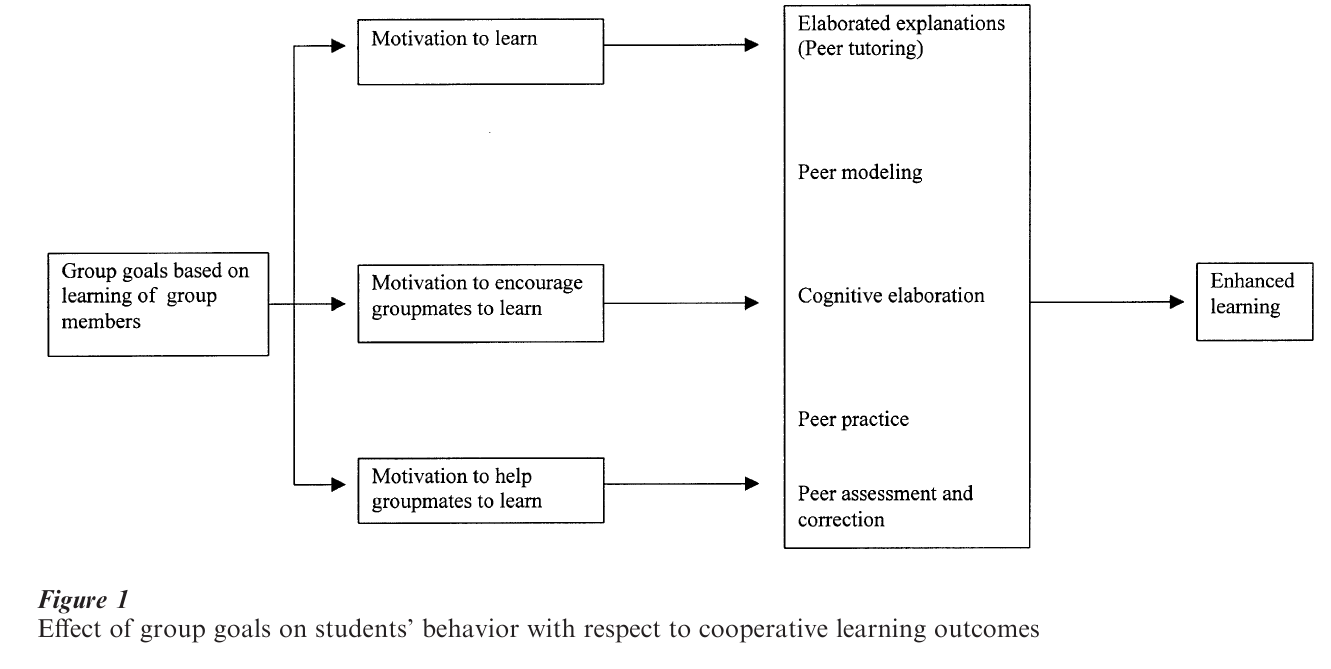

The various perspectives should be seen as complementary, not contradictory. While cognitively oriented strategies may not explicitly focus on motivation, motivational strategies invariably include peer interaction and cognitive engagement among group-mates. Figure 1 depicts a path through which group goals might directly affect students’ behavior to in turn enhance cooperative learning outcomes (from Slavin 1995).

Motivational theorists would not argue that the processes prioritized in cognitive models are unimportant, they simply argue that motivation drives such cognitive processes, which in turn produces learning effects. They would argue that over an extended period, students may not engage in the types of elaborated explanations that Webb (1989) credits for cooperative learning effects, without strategies directed at enhancing motivation. By extension, motivational theorists would hold that extrinsic incentives might affect achievement indirectly, by motivating students to engage in peer modeling, cognitive elaboration, and/or practice with one another. Extending this chain of influence farther, the provision of group goals may lead to group cohesiveness, increase caring, and concern among group members, and make group-mates feel responsible for one another’s achievement, thus motivating students to engage in cognitive processes that enhance learning. In addition, group goals may motivate students to take responsibility for one another independently of the teacher, thereby solving important classroom organization problems and providing increased opportunities for cognitively appropriate learning activities.

Referring to the model in Fig. 1, researchers from the cognitive perspective attempt to intervene directly on mechanisms considered mediating variables in the motivational view. For example, social cohesion theorists attempt to directly increase group cohesiveness by engaging in elaborate teambuilding and group processing training. One group investigation study suggests that this can be done successfully, but that it takes a great deal of time and effort. In this study, teachers were trained over the course of a full year, and then teachers and students used cooperative learning for three months before the study began. Earlier research on group investigation failed to provide a comparable level of preparation of teachers and students, and the achievement results of these studies were less consistently positive.

Cognitive theorists would hold that the cognitive processes that are essential to any theory relating cooperative learning to achievement can be created directly, without the motivational or affective changes discussed by the motivationalist and social cohesion theorists. This may turn out to be accurate, but at present demonstrations of learning effects from direct manipulation of peer cognitive interactions have mostly been limited to studies of very brief durations and to tasks that lend themselves to the cognitive processes involved. Most of the Piagetian conservation tasks studied by developmentalists have few practical analogs in the school curriculum. At the same time, there is research on reciprocal teaching in reading comprehension which shows promise as a means of intervening directly in peer cognitive processes. Long-term applications of Dansereau’s (1988) cooperative scripts for building comprehension of technical material and procedural instructions also seem likely to be successful.

The previous discussion has summarized evidence that generally supports the motivationalist view that group goals and individual accountability can be important to realizing the potential benefits of cooperative learning. This position is by no means absolute and there are conditions under which achievement gains have been found for cooperative learning treatments that lacked group goals, individual account-ability, or both. Structured dyadic tasks (e.g., Dansereau 1988) and voluntary study groups, as are often seen among college and graduate school students, are two other instances where factors inherent to the task or scenario may affect students sufficiently to render instructor-imposed group goals and individual accountability unnecessary. By the same token, there is little evidence that the presence of group goals or individual accountability would reduce the out-comes of these methods, and they are likely to enhance their effects. There is a clear need to explore such cases further, if only because the deeply rooted mistrust among educators for extrinsic incentives makes reward-free cooperative learning a practically valuable goal.

The practice of cooperative learning is entering a new phase. On one hand, it is so widely used and so infused in preservice and inservice education that it is no longer seen as an innovation. On the other, much of the application of cooperative learning is informal, unstructured, and inconsistent with the principles of effectiveness derived from any of the schools of thought described here. Cooperative learning often means students sitting together with no particular goal or structure. Where cooperative learning is most appropriately used is in more structured, comprehensive approaches that provide extensive professional development and materials designed specifically for use in cooperative learning. Examples include reciprocal teaching (Webb and Palincsar 1996), writing process, Cooperative Integrated Reading and Composition, and Success for All (Slavin and Madden 2001). These and related programs may represent the future of cooperative learning in the twenty-first century, where cooperative learning is becoming a basic element of comprehensive reform rather than only a generic process to be applied to every subject and grade level to the extent teachers wish to do so.

Research on cooperative learning is needed both to further understand cognitive and motivational mechanisms underlying its effects on achievement and to use this research to develop and evaluate new and increasingly effective forms of cooperative learning. After more than 30 years of research, the potential power of cooperative learning has been demonstrated and causal mechanisms have been extensively explored, but there is still much to be done to achieve the full potential of students working with students to achieve.

The evidence is strong indicating that cooperative learning has the potential to serve as a foundation upon which education in the twenty-first century will be built. Research must strive to provide practical, theoretical, and intellectual guidance to the efforts of educators the world over in the service of both traditional and innovative goals.

Bibliography:

- Aronson E, Blaney N, Stephen C, Sikes J, Snapp M 1978 The Jigsaw Classroom. Sage Publications, Beverley Hills, CA

- Cohen E G 1994 Designing Groupwork: Strategies for the Heterogeneous Classroom, 2nd edn. Teachers College Press, New York

- Damon W 1984 Peer education: The untapped potential. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 5: 331–43

- Dansereau D F 1988 Cooperative learning strategies. In: Weinstein C E, Goetz E T, Alexander P A (eds.) Learning and Study Strategies: Issues in Assessment, Instruction, and Evaluation. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 103–20

- Johnson D W, Johnson R T 1994 Learning Together and Alone: Cooperative, Competitive, and Individualistic Learning, 4th edn. Allyn & Bacon, Boston

- Johnson D W, Johnson R T 1996 Cooperative learning and traditional American values: An appreciation. NASP Bulletin 59: 63–5

- Kagan S 1995 Cooperative Learning Structures for Classbuilding. Kagan Cooperative Learning, San Juan Capistraumo, CA

- Mattingly R M, Van Sickle R L 1991 Cooperative learning and achievement in social studies; Jigsaw II. Social Behavior 55(6): 392–5

- Piaget J 1926 The Language and Thought of the Child. Harcourt Brace, New York

- Puma M J, Jones C C, Rock D, Fernandez R 1993 Prospects: The Congressionally Mandated Study of Educational Growth and Opportunity: The Interim Report. Abt Associates, Washington DC

- Sharan Y, Sharan S 1992 Group Investigation: Expanding Cooperative Learning. Teacher’s College Press, New York

- Slavin R E 1983 Cooperative Learning. Longman, New York

- Slavin R E 1995 Cooperative Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd edn. Allyn & Bacon, Boston

- Slavin R E, Madden N A 2001 One Million Children: Success for All. Corwin, Thousand Oaks, CA

- Vygotsky L S 1978 Mind in Society. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Webb N M 1989 Peer interaction and learning in small groups. International Journal of Educational Research 13: 21–39

- Webb N M, Palincsar A S 1996 Group processes in the class-room. In: Berliner D C, Calfee R C (eds.) Handbook of Educational Psychology. Simon & Schuster Macmillan, New York, pp. 840–73

- Yager S, Johnson R T, Johnson D W, Snider B 1986 The impact of group processing on achievement in cooperative learning groups. Journal of Social Psychology 126: 389–97