Sample Educational Research And School Reform Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, check out our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments at reasonable rates.

Educational research is a growing industry. Its aim is to make a contribution to knowledge. How this knowledge can be used, and in some cases if it can be used, to reform education forms the focus of this research paper.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

In 1899, William James in his Talks to Teachers on Psychology emphasized that education was ‘an art’ and not a science and could therefore not deduce schemes and methods of teaching for direct application from psychology: ‘An intermediary inventive mind must make the application by using its originality’ (p. 8). Nearly 100 years, later De Landsheere (1994 p. 1871) ‘Like medicine, education is an art. That is why advances in research do not directly produce a science of education, in the positivistic meaning of the term, but yield increasingly powerful foundations for practice and decision-making.’ Masters (1999), on the other hand, while making comparisons with medical research, suggests that in education research syntheses, sharper-focused research questions, and better communications between researchers and research utilizers, would do much to improve the link between research and school reform.

Husen (1994) suggested that the relationship between research and practice in policy-making had, for a long time, been conceived in a rather simplistic way. ‘Policy makers wanted research that primarily addressed their pressing problems within the framework of their perceptions of the world of education.’ They also wanted ‘recipes’ for their immediate problems (Husen 1989).

In 1960, there seemed to be general agreement that it would take at least one generation, about 15 years, between the results being produced by any of the then current research projects and their implementation at the school or classroom level. Since the 1960s, educational research has become a large enterprise with governments supporting it financially. Increasingly it is hoped that research can give pointers to the elements of reform that can either help to raise cognitive achievement, affective development and skills or cut the costs of education without damage to the desired outcomes.

This research paper deals with some of the different aspects of educational research, the contexts in which policy- making and research take place, the disjunction between researchers and policy-makers, and models of research utilization, and also presents some examples of the establishment of links between research results and action or reform.

1. Different Aspects Of Educational Research

Before proceeding with the link between research and reform, it would be desirable to deal with the various aspects of research.

Most policy-makers want, as mentioned above, clear results from research for the problems they have. These results should preferably be accompanied by a set of suggestions for reform or action. The research from which the results emanate should be ‘sound.’

Given that it is often extremely difficult, if not impossible, to conduct good experiments in education from which ‘cause and effect’ can be safely identified, researchers often have to depend on natural variation using survey samples. However, this depends on natural variation being there for the phenomenon under investigation. Class size is an example of where there is some variation in school systems but it is often within fairly narrow limits. Within a country, the average class size may be 25 children per class at a certain grade level. But the range is only 20–30. Yet, in other countries, the average class size may well be over 40 or even over 60. And in these other countries the range will be small. As another example, a country may wish to examine the differences between private and public schools, but if there are no private schools, then there is no natural variation. Furthermore, there is always the criticism that cross-sectional and longitudinal studies are ‘correlational’ and assumptions must be made about ‘cause and effect.’

The research must be ‘sound.’ Yet it can be argued that there are many studies that have technical deficiencies such that the results cannot be trusted. These deficiencies can include poor conceptualization, poor measurement, poor sampling and incorrect estimates of sampling error, inappropriate analyses, and false interpretations and conclusions. Some could argue that more unsound than sound research is produced in the field of education. The International Academy of Education produced a summary of ‘The requirements of a good study’ for sample surveys in international educational achievement studies (International Academy of Education 1999, Appendix 2). This attempts to describe in lay terms the kinds of points in research publications that policy-makers should look for when trying to decide whether or not the research was well conducted and trustworthy. It would be useful if summaries such as this one were to be produced for different types of research.

It is important that readers of research reports can identify if the research conducted was unsound and cannot be trusted. Many senior policy-makers do not have this ability and must rely on those skilled in these matters in their own ministries of education. Unfortunately, not all ministries have such people. The dangers of implementing policy based on poor research are obvious.

It is also the case that policy-makers need results that have, if possible, been replicated and that are generalizable to a grade level or general level (e.g., junior high school or elementary levels of education) in an educational system, and where the effects are large. Research that is only applicable to a few specific schools (case-study approach) is not of interest to them. Furthermore, the research should ideally be applicable to several key subjects in school and not just to one subject. Ministries allocate resources to schools and they want the resources to have wide application in each school and not just to one subject. Unfortunately, having results on the effect of variables on several subjects at the same time is costly and time consuming.

Keeves (1994) has distinguished between research studies associated with the generation of change and those that serve to maintain and consolidate existing conditions. It is the second type of research that he calls ‘legitimatory research.’ Thus the motivation for commissioning research must also be taken into account when viewing the links between research and change.

2. Contexts For Policy-Making And Research

2.1 For Policy-Making

As already stated, policy-makers are interested in their problems within their current frame of reference and understanding of education. They perceive of what researchers know as ‘fundamental’ research to be of no, or only peripheral, interest to them. What the policy-makers perceive to be of interest can change with a change of government. For example, the matters of bussing, educational vouchers, and private schools had different priorities under the Carter and Reagan administrations in the USA. Equality of educational opportunity, on the other hand, has had a high priority under various administrations in various countries. In the second project of the Southern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ), chief policy-makers in 14 southern African countries were asked to rate issues that were of interest to them in primary schooling. One of the issues was that of private tuition outside school. This was given very low priority despite the fact that the first study of SACMEQ had shown the practice to be very widespread, for the most part to affect achievement even after home background had been accounted for. It was later given a higher priority after the researchers had interacted more with the policymakers.

Policy-makers have allegiances that influence both what they regard as relevant, innocuous or even ‘dangerous’ research and also their willingness to take account of research findings. Stories abound of ministries or government departments either ignoring research results or delaying the publication of government-sponsored research because the results did not accord with the current political interests. Ways of delaying the publication of research results that governments do not like have been hilariously resumed in ‘Yes Minister’ (Lynn and Jay 1982). Not only can research be delayed or ignored but also only partial results can be selected to help them argue a case. Keeves (1994) has dealt with many of the problems that arise with those in authority when conducting legitimatory research.

Governments, as a rule, last only a few years. The research they sponsor should be completed within that time period and preferably in less than two years. There are few research projects that can be completed in this time period when it is considered that the instruments have to be developed and tried out before the major data collection can begin. The findings should be made available in time for the decisions that have to be taken and which will go ahead with or without the necessary knowledge base. Operational decision-making cannot wait for the results of specifically sponsored research results.

It has sometimes occurred that governments have initiated a reform, often without much evidence of its worthwhileness, and then asked for research to be undertaken to assess its effect. Where the reform has been total, it is too late to compare the effects of the reform with any other form of education. Even if the reform has been in some and not all schools, the problem has arisen that the government wants quick results and yet it takes some time for an innovation to ‘settle down.’ It is not good, or even dangerous, to judge its effects in the first year of operation.

2.2 For Researchers

The researchers often tend to have different backgrounds and value systems from those of the policymakers. Researchers have usually undertaken their work in research institutes or university settings. Researchers have been trained to think widely and to question all things. Their allegiance tends to be more to fundamental or conclusion-oriented research. They pay much more attention to how the quality of their research is received by their research peers than by government agencies.

In most cases, researchers are not involved in the planning and implementation of reform. They rarely have any interest in how to plan the costs involved in any reform. They can rarely phrase their results in the language of planning and implementing reform. Indeed, once they have published their research report they tend to lose interest in what happens after that.

Status in the research system depends on the reputation the individual researcher gains from his or her research work. Status in the administrative world tends to be based on seniority and length of service and not on the quality of research work.

3. Disjunction Between Researchers And Policy Makers

From the above, it can be seen that the ‘ethos’ pervading in the contexts in which researchers and policy-makers live is very different. In nearly all cases, the researcher has to write a proposal for the research project that he or she must submit for funding. Very often the researcher views the proposal from the point of view of its likely contribution to knowledge whereas the policy-maker examined it from the point of view of the relevance to the ministry’s agenda. Education is value based and has certain underlying ideologies. It is a short step, therefore, to the political arena. It can often happen the governments view social science research with suspicion because when they want the status quo to be preserved social science research that wants to go to the root of the matter in the sense of critical inquiry can be seen as subversive radicalism. On the other hand, some social scientists—because of the relationship between education and certain political and social philosophies—have begun to act as evangelists and this has damaged their credibility.

In the 1960s, governments began to support social and behavioral sciences research on a hitherto unprecedented scale. This was particularly true in countries such as the USA, UK, and Sweden (Aaron 1978). It was not long before there were discrepancies between expectations on the part of the policy-makers and the actual research performance. There was a decreasing credibility of research work on the part of the policy-makers that began in the early 1970s.

4. Models Of Research Utilization

Weiss (1979) distinguished among seven different models of research utilization in the social sciences (see also Husen 1994):

(a) The R&D model. This is a ‘linear’ process from basic research to applied research and development to application. Weiss pointed out that the applicability of this model was limited in the social sciences because knowledge in the field does not lend itself easily to ‘conversion into replicable technologies, either material or social’ (Weiss 1979, p. 427).

(b) The problem-solving model. Here the results from a specific project are expected to be used directly in a decision-making situation. The process consists of: identification of missing knowledge acquisition of research information either by conducting a new study or by reviewing the existing body of knowledge interpretation of the results given the policy options available decision about which policy to pursue. This model has sometimes been known as the ‘philosopher-king’ approach where researchers are supposed to provide the information from which policy-makers derive guidelines for action. The problem-solving model often tacitly assumes about goals but social scientists do not agree among themselves about the goals of certain actions. Nor is there necessarily agreement among all policy-makers about the goals.

(c) The interactive model. This model assumes an ongoing dialogue between researchers and policy-makes. This is usually a disorderly set of interconnections and back-and-forthness.

(d) The political model. Research findings are used as ammunition to defend a particular point of view. It is often the case that policy-makers have already made up their mind about taking a particular course of action and should there be research results that legitimize this, then they will use it.

(e) The tactical model. This is a negative approach in that it is a way of deferring any decision. Thus, a controversial issue can be buried or postponed by policy-makers calling for more research or further analyses.

(f) The enlightenment model. According to Weiss (1979, p. 428), this is the model where social science research most frequently enters the policy arena. Research can ‘enlighten’ policy-makers because as research results become available they sensitize informed public opinion about ways of thinking of educational problems and come to shape the way in which people think about social issues. This is sometimes known as the percolation effect. People are helped to redefine problems through research so that they begin to think of the problems in a different way.

(g) The research-oriented model. Weiss (1979) refers to this as the ‘research-as-part-of-the-intellectual enterprise-of-society’ model. Social science research together with other intellectual inputs, such as philosophy, history, journalism, and so on, contribute to widening the horizon for the debate ion certain issues and to reformulating the problems. This is somewhat akin to the enlightenment model outlined above.

Shavelson (1988, pp. 4–5), when dealing with the utility of social science research, sought to reframe the issue of ‘utility’ by suggesting ‘that the contributions lie not so much in immediate and specific applications but rather in constructing, challenging, or changing the way policy-makers and practitioners think about problems.’ He suggested that one cannot expect educational research to lead to practices that make society happy, wise, and well-educated in the same way that the natural sciences lead to a technology that makes society wealthy. The assumption that ‘educational research should have direct and immediate application to policy or practice rests on many unrealistic assumptions’. Among these are relevance to a particular issue, provision of clear and unambiguous results, research being known and understood by policy-makers, and findings implying other choices than those contemplated by policy-makers.

5. Some Examples

It is relatively easy to identify some research that has had an enlightenment effect. The work of Piaget in identifying ‘stages of development’ began to have an effect on work in curriculum development by the end of the 1950s. Bloom’s ‘Taxonomy of Educational Objectives’ and ‘Model of School Learning’ had a marked effect on many later research projects, the results of which entered the market place and influenced educational thinking. Coleman’s ‘Equality of Educational Opportunity’ produced the concepts of ‘school climate’ and later ‘social capital,’ both of which entered educational thinking. The ‘Plowden Report’ in England produced the concepts of parental attitudes and ‘educational priority zones,’ both of which entered the general educational thinking. Carroll’s ‘model of school learning’ and later his ‘human cognitive abilities’ research both influenced how educators thought of school learning. However, in all of these cases, the process took a long time. In some special cases in Sweden in the late 1950s and early 1960s research studies led directly to some action especially in the revision of the curriculum. However, the direct effect examples are rare.

In the first two decades or even more of the work of the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) (Postlethwaite 1994), a massive amount of effort went into attempting to identify the major determinants of educational achievement in each of the participating countries. It was to the chagrin of the research workers that very little attention was given to the results. It was rather the ‘horse race’ national mean achievement levels that gained the attention of the press and the policymakers. In the 1970s the then Minister of Education talked of the results being like an electric shock because they showed that the gap between north and south Italy was much larger than had been expected. The Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) of IEA (see, for example, Beaton et al. 1996) in the 1990s only presented aggregate estimates for the test scores and selected questionnaire variables in their first set of publications and did not present analyses identifying the major determinants of either between country differences, or between-school or between student differences within countries. Nevertheless, it was these aggregated estimates that attracted enormous media publicity and comment. In some cases the comment was appropriate such as about the high achievement scores in Japan but the low attitudinal scores towards the learning of the subject. In other cases, several of the journalists’ comments and even those of some ministry officials proffering policy suggestions assumed that the relationships between certain variables between countries would be the same as those within countries (Ross 1997). The question must be asked as to why the press and the ministries seem to be more interested in the mean score differences rather than in the determinants of such differences. Is it possible that an interface of persons skilled in translating research findings into policy suggestions is needed?

Several of these kinds of projects did attempt to communicate to schools that participated in the research and would send each school a school report. This typically consisted of giving the test scores for each child in the sample in the school, the school’s mean scores on the test as a whole and on subscores, the mean scores of similar schools and the mean scores of the nation. It was assumed that these kinds of results would enable school principals to identify the weak parts of achievement in his her school and then be able to take remedial action. It would seem that some school principals did take the feedback seriously, but many did not do so.

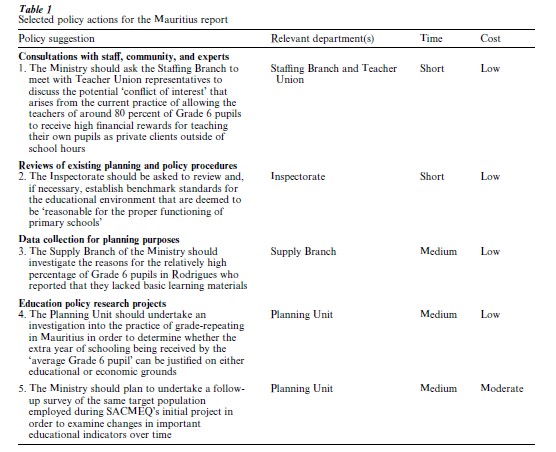

By the beginning of the 1990s, some progress was being made in the attempt to have educational planners and administrators work more closely with educational researchers in order to have more direct links between research and policy-making. One international study in the 1990s had the strategy of working out in conjunction with ministries of education the research questions and then working out the actions to be taken as a result of the findings. This latter step was undertaken before the research reports were finalized for publication. This study was that of the Southern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ). The last chapter of each national publication listed the suggested policy actions categorized by cost and time needed for implementation. An example is given in Table 1 of selected suggested policy actions for the Mauritius report (Kulpoo 1998, pp. 86–92). There were 38 policy suggestions in all.

It should be noted that the units undertaking the research study were units within the Ministry of Education and not special research units either within the ministry or in higher education institutes. The actual suggestions were checked, and in one or two cases modified, by the senior ministry personnel before the book was published. To what extent the suggestions were implemented is not yet known. On the other hand, there was a similar study in Zimbabwe with similar policy suggestions in 1991 and a report documenting the implementations of the suggestions has been published (Ross 1995). Despite the fact that some of the suggestions were implemented, there was no improvement in Grade 6 reading achievement by 1997 (Shumba 1998). It is unclear whether the implementation was not well conducted or whether only some of the easier but not crucial suggestions were implemented. This will also apply to the other SACMEQ reports.

In the USA, the United States Department of Education (1986) published a booklet under the title What Works: Research About Teaching and Learning. This booklet reported the results of research syntheses. It was aimed at all involved in education and presented in one or two pages the results of research and the practical implications of those results. This was followed by a series of similar booklets on different aspects of education. These booklets were made available to all schools in the USA. This was an attempt to communicate directly with school principals and teachers and was said to be very popular.

From the mid-1980s onwards there has been a movement initiated by Ministries of Education known as the ‘Indicators Movement.’ The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has coordinated this work and produced a series of annual reports called ‘Education at a Glance’ (see the most recent one at the time of writing, OECD 1998). Data are collected and aggregated and reported at the national level. In some cases these results are of interest. There is the danger that the correlation of two variables/indicators at the national level is not the same as at the within country between school or between student levels (cf., Ross 1997). Where policy is made on the basis of the national level correlations and the within-country correlations are different, this can lead to misleading policy. It is important to examine the relationships at different levels before arriving at suggested action for policy-making. The OECD has begun to overcome this problem by having initiated a ‘Program for International Student Assessment’ (PISA), where every four years students aged 15 years (i.e., just before the end of compulsory schooling in most countries) will be tested in mathematics, science, and reading as key subjects and variation in achievement will be analyzed at student, school, and country levels. Data were also collected on student and school background variables (indicators) and will be related to variation in student outcomes.

There has been a host of research studies on such topics as learning, programmed instruction, leadership (authoritarian, democratic, and laissez-faire), grouping of students and achievement outcomes, learning methods, motivation (expectations of success and failure), grading practices, creativity and teaching methods, language (and foreign language) learning, the regularity and sequencing of in-service teacher training programs, teaching styles, and so on. Many suggestions have emanated from such research but in some cases there were contradictory results from different studies or the suggestions, even from sound research, were ignored. In some countries, there has been a tendency to initiate ‘bottom-up’ reform from examples from single schools. These have been casestudy type research and have suffered from two defects: they could not be generalized in the sense of knowing how the innovation would work in many schools, and in many cases they were successful because of the charisma of a particular individual. When attempts have been made to replicate the innovation on a larger scale, there have been problems.

6. Conclusions

A great deal of money goes into educational research and yet the results are rarely used directly. Indirectly and over time research results ‘percolate’ down (one of the Weiss models of research utilization) to the district and school levels and then demands are made on the policy-makers to ‘do something.’ Even when policy-makers take the results seriously, there remains doubt about how well the implementation of policy suggestions was carried out.

If research is in some cases to have a more direct link to school reform it would seem as though several steps should be taken:

(a) Researchers should talk to the policy-makers before the research begins and ensure that the design and proposed analyses will answer the policy-makers’ concerns.

(b) Projects should be conducted in a sound technical way. This requires that the funders have a cadre of persons that can advise them about the technical soundness of the proposed research. This is a big step because there are not many ministries even in highly developed countries that possess such persons.

(c) Projects should, wherever possible, be replicated. (d) Researchers should, after consultation with the policy-makers, make a list of suggested actions for reform.

(e) Ministries of education should train and employ a cadre of policy researchers who are able to translate the research results into suggested actions that constitute the crucial actions and not only those easy to conduct. These persons may not necessarily be within the ministry but could be in university departments.

(f) Policy suggestions should be acted upon and well implemented.

(g) Studies should be conducted to assess the effect of the implementations.

Until these kinds of steps are taken, research will continue to have its indirect enlightenment effect.

Finally, it should be remembered that there are certain reforms that do not depend on research. When the great debate raged in the 1960s in Europe about comprehensive schooling versus selective schooling it was the then Minister of Education in England and Wales who wrote, when asked why England has not preceded ‘going comprehensive’ with research such as that conducted in Sweden, ‘It implied that research can tell you what your objectives should be. But it can’t. Our belief in comprehensive reorganization was a product of fundamental value judgements about equity and equal opportunity and social division as well as about education. Research can help you to achieve your objectives, and I did in fact set going a large research project, against strong opposition from all kinds of people, to assess and monitor the process of going comprehensive. But research cannot tell you whether you should go comprehensive or not—that’s a basic value judgement’ (Husen and Kogan 1984).

Bibliography:

- Aaron J H 1978 Politics and the Professors: The Great Society in Perspective. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC

- Beaton A E, Mullis I V S, Martin M O, Gonzales E J, Kelly D, Smith T A 1996 Mathematics Achievement in the Middle School Years: IEA’s Third International Mathematics and Science Study. TIMSS International Study Center, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA

- De Landsheere G 1994 Educational research, history of. In: Husen T, Postlethwaite T N (eds.) International Encyclopedia of Educational Research. Pergamon Press, Oxford, UK, Vol. 4, pp. 2053–9

- Husen T 1989 Educational research at the crossroads? An exercise in self-criticism. Prospects 19(3): 351–68

- Husen T 1994 Educational research and policy-making. In: Husen T, Postlethwaite T N (eds.) International Encyclopedia of Educational Research. Pergamon Press, Oxford, UK, Vol. 3, pp. 1793–7

- Husen T, Kogan M (eds.) 1984 Educational Research and Policy: How Do They Relate? Pergamon Press, Oxford, UK

- International Academy of Education 1999 The Benefits and Limitation of International Studies of Educational Achievement. IIEP, Paris

- James W 1899 Talks to Teachers on Psychology: and to Students on Some of the Life’s Ideals. Longmans Green, London

- Keeves J P 1994 Legitimatory research. In: Husen T, Postlethwaite T N (eds.) International Encyclopedia of Educational Research. Pergamon Press, Oxford, UK, Vol. 6, pp. 3368–73

- Kulpoo D 1998 The Quality of Education: Some Policy Suggestions Based on a Survey of Schools: Mauritius. SACMEQ Policy Research: Report No. 1. Ministry of Education and Human Resource Development, Mauritius and International Institute for Educational Planning, Paris

- Lynn J, Jay A (eds.) 1982Yes Minister: The Diaries of a Cabinet Minister by the Rt. Hon. James Hacker MP. Vol. 2. British Broadcasting Corporation, London

- Masters G N 1999 Valuing educational research. ACER Newsletter Supplement, No. 94. Australian Council for Educational Research, Melbourne, Australia

- OECD 1998 Education at a Glance: OECD Indicators. Organisation for an Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris

- Postlethwaite T N 1994 Educational achievement: comparative studies. In: Husen T, Postlethwaite T N (eds.) International Encyclopedia of Educational Research. Pergamon Press, Oxford, UK, Vol. 3, pp. 1762–69

- Ross K N 1995 From educational research to educational policy: an example from Zimbabwe. International Journal for Educational Research 23: 301–403

- Ross K N 1997 Research and policy: a complex mix. IIEP Newsletter 15(1): 1–4

- Shavelson R 1988 Contributions of educational research to policy and practice: constructing, challenging, changing cognition. Educational Researcher 17: 4–11, 22

- Shumba S 1998 Was there a change in reading-literacy levels for Grade 6 pupils in Zimbabwe during the period 1991 to 1995? In: Machingaidze T, Pfukani P, Shumba S (eds.) The Quality of Primary Education: Some Policy Suggestions Based on a Survey of Schools. SACMEQ Policy Research Report No. 3. IIEP (UNESCO), Paris and Ministry of Education and Culture, Zimbabwe

- United States Department of Education 1986 What Works: Research About Teaching and Learning. US Department of Education, Washington, DC

- Weiss C 1979 The many meanings of research utilization. Public Administration Review 39: 426–31