Sample Group Processes In The Classroom Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Interest in group learning and group processes has a very long history and remains a key focus of current efforts to improve education. Group processes in the classroom occur when peers engage in a common task and can include a variety of both social and cognitive processes. The focus of this research paper is on cooperative or collaborative groups of peers and the various theoretical approaches that attempt to explain group processes in these kinds of group. These approaches propose varying mechanisms for the effectiveness of group learning. Comparisons of empirical findings across studies conducted from different theoretical perspectives are very difficult because of the wide variances in tasks used, duration of studies, roles of teachers and students, outcome measures, and other variables such as group composition. One consequence of the variance in theoretical approaches is the fact that these approaches require different decisions with regard to key variables such as group size or group composition. Group processes can best be understood within particular theoretical approaches. This research paper will not address the influences of specific variables but will instead focus on the delineation of various theoretical perspectives and the linkage of research and practice.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Theoretical Approaches To Group Processes

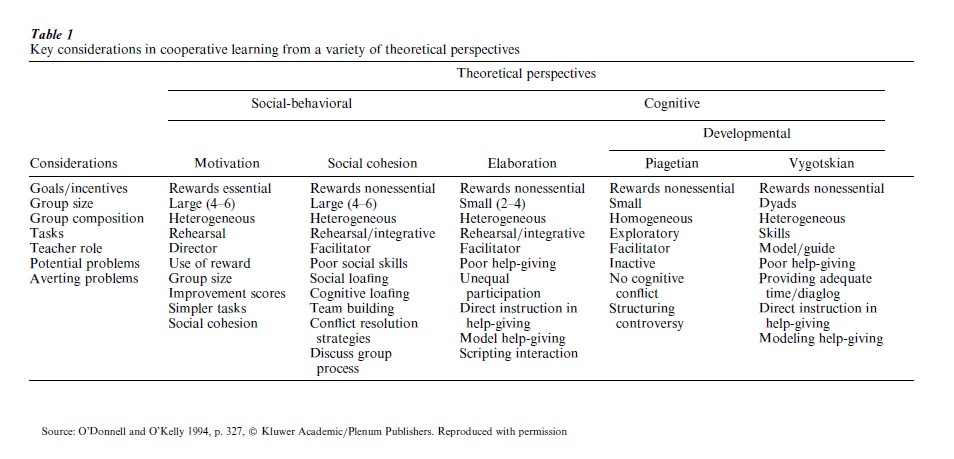

Different theoretical approaches to peer learning propose different underlying mechanisms or processes that come into play when a group works together (O’Donnell and O’Kelly 1994). Slavin (1996) described two main classes of orientation toward peer learning: a social-behavioral orientation that includes motivational and social cohesion approaches, and a cognitive orientation that includes elaboration and developmental perspectives. There are two distinct developmental theories. Table 1 delineates key differences among these perspectives as they relate to instructional decisions and problems that may arise from such decisions.

1.1 Social-Behavioral Perspectives

The concept of interdependence among group members is fundamental to the motivational and social cohesion perspectives on cooperative learning, although they differ in how interdependence is created and sustained. When group members are interdependent, the success of one member can occur only if other members are also successful. In competitive situations, one person’s success requires that another person fail. In the social motivational approach, interdependence is created by the use of group rewards. In Student Teams Achievement Divisions (Slavin 1995), students work in small groups to master material that the teacher has presented. Each student takes an individual quiz on the material, and points are assigned to the group based on each individual’s improvement score. Thus, students are accountable for improving over past performance and learners of varying abilities can contribute equally to the total group score. Group rewards are assigned based on the team’s number of points. A key component of this approach is the reliance on individual accountability. Evidence of the effectiveness of this approach comes from a large number of studies (Slavin 1996). The kinds of learning task used in this approach, however, tend to focus on basic skills or factual knowledge, and it is unclear whether this approach is effective in promoting higher-order skills.

1.2 Social Cohesion Perspectives

In the social cohesion approach, interdependence derives from a motive of care and concern. Group members help one another because they are concerned about their peers. Teaching social skills that will support this type of interdependence is an important emphasis in social cohesion approaches. The Johnsons’s Learning Together technique (Johnson and Johnson 1994) illustrates the social cohesion approach. The empirical evidence supporting this orientation toward group learning as a means of enhancing academic achievement is much weaker than that supporting the motivational perspective. Slavin (1996) notes that cooperative learning methods that emphasize team building and group process, but do not provide group rewards, are not very effective but that when they are combined with the use of rewards or accountability, student achievement from group learning exceeds individualistic learning. Slavin concludes that individual accountability and group rewards are critical to the success of cooperative learning methods.

Not everyone subscribes to the idea that rewards are necessary to create cohesion or interdependence. Cohen (1994) believes that cooperative learning that uses group rewards may be useful for lower-level skills but may not be either necessary or helpful for promoting higher-order skills. Thus, decisions about whether to adopt a motivational or social cohesion approach to peer learning may depend on the desired outcomes from group interaction.

Cohen (1994) emphasizes a different source of social cohesion, suggesting that the interest value of the task in which students engage will create the kind of interdependence necessary for students to succeed. In such situations, difficulties associated with status differences among students are ameliorated. When students have low status in the group, they participate less and in ways that do not promote achievement. Explicit rewards in this context may only exacerbate the problems created by differential status in a group. Cohen and her colleagues have successfully promoted social cohesion in groups by reducing status differences among group members so that they are oriented to accept that all students can contribute to task accomplishment. Complex and interesting tasks are necessary for this level of inclusion to occur. Cohen and her colleagues have been very successful in promoting student achievement. Results from Cohen and her colleagues suggest that the nature of the task may have important implications for the kind of accountability that is needed to promote effective group learning.

1.3 Cognitive/Elaborative Perspectives

The third perspective identified by Slavin is a cognitive elaborative approach and is based on information processing theory. The role of the group interaction from this perspective is to increase active processing by providing opportunities for restructuring and elaborating knowledge. Group learning techniques influenced by this perspective tend to provide some structure to the interaction of students by emphasizing the cognitive processes in which students must engage. Examples of work influenced by this perspective include the use of scripted cooperation by O’Donnell, Dansereau, and colleagues (O’Donnell and Dansereau 1992), reciprocal peer questioning (King 1999), reciprocal teaching (Palinscar and Brown 1984), and the work of Noreen Webb (Webb 1992). The empirical evidence supporting the use of these techniques is strong.

The quality of discourse is critical from this perspective and will have an influence on the outcomes from group interaction. Webb (1992, Webb and Palinscar 1996) has shown that the quality of explanations that are provided in a group are linked to achievement. Giving explanations is more strongly associated with achievement than receiving explanations. King (1999) has also shown that instructional efforts to improve the quality of discourse by teaching students to ask questions that facilitate knowledge construction is very effective.

1.4 Developmental Perspectives

A fourth approach to understanding cooperative groups relies on two different theories of development. From a Piagetian perspective (De Lisi and Golbeck 1999), peers can learn from one another because they can provide opportunities for cognitive conflict and resolution. Groups that experience mutuality of influence and power are most likely to provide a context within which cognitive development can occur because they are more likely to include differences of viewpoint. Children who have not attained the principle of conservation often develop and maintain conservation concepts when they have worked with a child who has already developed this concept (De Lisi and Golbeck 1999). Much of the work on conceptual change in science education has been influenced by this perspective.

From a Vygotskian perspective (Hogan and Tudge 1999), children acquire knowledge and skills that are first modeled in the community and are subsequently internalized by an individual. When cooperative learning is anchored in Vygotskian theory, it is concerned with the larger community of practice in which individual learning is accomplished. Key processes include the scaffolding of the learner’s performance by a more expert individual. The difference between what an individual can accomplish alone and with the assistance of an adult guide or more capable peer is defined as the zone of proximal development.

1.5 Sociocultural And Combined Theoretical Perspectives

A fifth perspective that undergirds such group learning techniques such as Communities of Learners (Brown and Campione 1990) may be identified. It includes the developmental perspective of Vygotsky, with its emphasis on the sociocultural basis of learning, and a social cohesion approach in which such learning is motivated by care and concern. Other forms of cooperative learning borrow from multiple perspectives in making choices about the selection of tasks and the organization of learning (Van Meter and Stevens 2000).

2. Research And Practice

Despite the burgeoning research findings that might assist teachers in making choices about grouping for instructional purposes, teachers do not seem to rely on the empirical research for guidance when making such choices (Antil et al. 1998). However, few studies have examined teachers’ beliefs about group processes in the classroom.

2.1 Teachers’ Use Of Cooperative Learning

The research findings from any of the perspectives previously described seem to have little systematic influence on teachers’ choices about groups. Although Slavin (1996) is convinced that empirical evidence supports the use of group rewards, he notes that there is quite a reluctance on the part of classroom teachers to use them.

Antil and his colleagues (1998) conducted a study of elementary school teachers’ conceptualization and utilization of cooperative learning. Eighty-five teachers responded to an initial survey, and 93 percent of them reported that they used cooperative learning for both academic and social reasons. In interviews with 21 of these teachers, Antil found that the majority structured tasks to create positive interdependence, and taught students skills for working in groups. Few, however, employed recognized forms of cooperative learning and, in particular, did not link individual accountability to group goals. No data were presented, however, that linked classroom practices in relation to cooperative learning and student achievement. It is clear from this study that teachers do not implement the particular practices of cooperative learning that research has shown to be effective. However, when teachers receive extensive professional development, the effects on student achievement can be powerful (Schultz 2000).

2.2 Usable Models Of Group Processes

The availability of multiple perspectives on peer learning and the proliferation of specific techniques may contribute to the disconnection between the available research findings and their use by classroom teachers. The kind of classification system represented in Table 1 is rarely presented to either pre-service or inservice teachers. Usable models of peer learning that can guide practical decisions are needed. Such models need clearly to link expected outcomes to classroom processes and teachers’ actions or decisions.

Slavin (1996) proposed a model of effective peer learning with motivation at its core. Motivation is necessary in order for students to engage in the active processing (e.g., explanations) that is linked to achievement. The keys to motivating students are group rewards and individual accountability. Teachers can act to create and sustain children’s motivation that will allow them to link will and skill in pursuit of achievement.

Van Meter and Stevens (2000) emphasize the quality of discourse in a group as the key variable in effective group learning. Other instructional choices should be such that the quality of discourse is enhanced. Thus, task instructions and group composition are only interesting insofar as they influence the quality of the discourse among peers.

These two models provide a simple set of goals for teachers using group learning. Coherence among classroom decisions about fundamental aspects of arranging instruction (e.g., group size, group composition, type of task) is more likely to occur if there is a clear goal in place (e.g., motivate students to engage in active learning). Teachers in the Antil et al. (1998) study reported that they did not subscribe to particular cooperative techniques because they wanted to maintain their decision-making autonomy. The two models that are briefly described here with their emphases on motivation and discourse provide a set of superordinate goals that can accommodate teachers’ needs for autonomy, while preserving a principled approached to decision making about group processes.

3. Future Directions

Given that teachers seem reluctant to use group rewards (Slavin 1996), it is important to specify the conditions under which alternative methods of creating interdependence among group members can be effective. What are the kinds of tasks for which extrinsic reward are not necessary? Answers to this question lie in the analysis of the kinds of process in which students engage when they are engaged in interesting and challenging tasks. A clearer understanding of effective processing of complex tasks may make it possible to find alternatives to rewards.

The tension between theories of group processes and classroom practices of group learning presents the richest source of future research questions. Teachers’ beliefs about learning lie at the fulcrum of their abilities to implement effective group learning in the classroom. The relationships between teacher beliefs, implementation practices, and student achievement remain untouched as research questions. Research on this set of relationships would provide valuable insights that could inform teacher preparation and in-service professional development, and also improve classroom practice of group learning.

Bibliography:

- Antil L R, Jenkins J R, Wayne S K, Vadasy P F 1998 Cooperative learning: Prevalence, conceptualizations, and the relationships between research and practice. American Educational Research Journal 3: 419–55

- Brown A L, Campione J C 1990 Communities of learning and thinking, or a context by any other name. Developmental Perspectives on Teaching and Learning Thinking Skills 21: 108–26

- Cohen E G 1994 Restructuring the classroom: Conditions for productive small groups. Review of Educational Research 64: 1–35

- De Lisi R, Golbeck S 1999 Implications of Piagetian theory for peer learning. In: O’Donnell A M, King A (eds.) Cogniti e Perspecti es on Peer Learning. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 3–37

- Hogan D, Tudge J H R 1999 Implications for Vygotsky’s theory for peer learning. In: O’Donnell A M, King A (eds.) Cogniti e Perspecti es on Peer Learning. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 39–65

- Johnson D W, Johnson R 1994 Learning Together and Alone: Cooperative, Competitive, and Individualistic Learning, 4th edn, Allyn and Bacon, Boston

- King A 1999 Discourse patterns for mediating peer learning. In: O’Donnell A M, King A (eds.) Cognitive Perspectives on Peer Learning. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 87–115

- O’Donnell A M, Dansereau D F 1992 Scripted cooperation in student dyads: A method for analyzing and enhancing academic learning and performance. In: Lazarowitz R, Miller N (eds.) Interaction in Cooperative Groups: The Theoretical Anatomy of Group Learning. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 120–41

- O’Donnell A M, O’Kelly J 1994 Learning from peers: Beyond the rhetoric of positive results. Educational Psychology Review 6: 321–49

- Palinscar A S, Brown A 1984 Reciprocal teaching of comprehension monitoring activities. Cognition and Instruction 2: 117–75

- Schultz S E 2000 Are Four Heads Better than One? Effects of Group Work on Students’ Achievement in Science. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA

- Slavin R E 1995 Cooperative Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd edn. Allyn and Bacon, Boston

- Slavin R E 1996 Research on cooperative learning and achievement: What we know, what we need to know. Contemporary Educational Psychology 21: 43–69

- Van Meter P, Stevens R J 2000 The role of theory in the study of peer collaboration. Journal of Experimental Education 69: 113–27

- Webb N M 1992 Testing a theoretical model of student interaction and learning in small groups. In: Lazarowitz R, Miller N (eds.) Interaction in Cooperative Groups: The Theoretical Anatomy of Group Learning. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 102–19

- Webb N M, Palinscar A S 1996 Group processes in the classroom. In: Berliner D, Calfee R C (eds.) Handbook of Educational Psychology. Macmillan, New York