Sample Educational Institutions And Society Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

The analysis of relationships between educational institutions and society presupposes at least minimal conceptions of institutions and societies as social systems

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Educational Institutions

1.1 School Systems As Institutions

There is widespread agreement in sociological theory that institutions are social creations that serve to solve basic problems of society—e.g., to produce essential goods (economic institutions), to regulate sexual needs and biological reproduction (marriage and family), to resolve conflict (legal and political institutions), etc. Educational systems can also be regarded as large-scale problem-solving institutions. Confronting human genetic plasticity and the ability to learn to meet the complex needs of social life reveals the necessity of cultural reproduction via educational institutions. Educational systems form the highly institutionalized and/organized part of the total educational service of a society for the new generation.

Given this background, the question arises as to which societal problems an educational system responds in a highly complex society and what it contributes as an institution for society at large. The answer is that above all educational systems solve cultural reproduction problems, i.e., problems of reproducing the culture and social structure of a society in the light of the biological exchange of its members. Each new generation, for instance, must learn to read and write if the society is not to decline into a more primitive state. A certain technology can only be maintained if we also have future technicians and engineers who, for instance, can build and repair television sets, cars, and computers.

To solve these problems of reproduction, school systems have been created during long historic processes of intentional ‘institution building.’

1.2 School Systems As Places For Socially Controlled And/Organized Learning

Content and ways of learning are structured and arranged in educational institutions on behalf of outside authorities. They express the power of social groups interested in specific content and processes of education. The socially desired learning processes are enforced in school systems by legal procedures and sanctions, by providing learning material and personal resources, and by systematically developing teaching know-how via elaborated training procedures.

1.3 School Systems As Socialization Agency

The third and central element of our concept of schools characterizes them as socialization agencies. Any process is labeled socialization if it at the same time constitutes psychological structures and reproduces cultural and social structures. School systems socialize children and adolescents via training qualifications and teaching values, without which the individual would be unable to function in society. At the same time, social reproduction and societal functioning is perpetuated. School systems are thus subsidiary arrangements; they emerge when mere participation in the social life of the family and kin group no longer suffices to teach all that is required for the functioning of society.

It is evident that reproduction is the main function of school systems, but school systems are also instruments of social change, proposed by social groups in charge of educational government.

2. The Structural-Functional Approach: Society And Institutionalized Education

In the 1960s, two sociological theories became prominent as frameworks for the formulation of the relationships between educational institutions and society: first the structural functionalism of Parsons, and secondly the framework of English social anthropologists (Halsey).

Here for the first time the basic idea is formulated rigorously:

(a) All societies maintain themselves with the help of a culture, i.e., with a complex set of attitudes and skills which are not contained in the genetic constitution of an individual but must be learned. This social heritage must be transmitted by social organization. Education has this function of cultural transmission in all societies.

(b) Individuals’ personalities must be formed so that they fit into a culture. Everywhere, education has the function of forming social personalities. As culture is transmitted by influencing personality, education contributes to integration of society whereby society can be seen as a mechanism which enables humanity to adapt to its environment, to survive, and to reproduce. (Halsey 1973 p. 385)

In his famous essay ‘The school class as a social system,’ Parsons (1959) explicated two functions of modern educational systems, namely socialization and selection. With socialization Parsons conceptualizes the process of passing skills on to each new generation, thus allowing them to fulfill tasks in an occupation and as a citizen. The function of selection leads to an allocation of students to occupational positions matching their abilities and interests. The structure of the school class is ideally suitable for fulfilling these tasks by modeling the processes of qualification and allocation. Dreeben (1968) continued these lines of reasoning by contrasting the social structure of the family and the school and by explicating the corresponding norms and values. Thereby the family represents a particularistic institution where each member occupies a unique status. In contrast, the school is seen as a universalistic social system where students are treated as equals and difference is attributed by universalistic norms of achievement.

An influential analysis of the relationship between school system and society originates from the French language area. The sociologists Bourdieu and Passeron (1977) became the first since the important work of Durkheim (1956), to provide internationally recognized contributions clarifying relationships between the educational system and social class (Bourdieu and Passeron 1977). Using the example of the higher educational system in France, they postulated the split between the official ideology of achievement based on upward mobility and the actual rules for social reproduction. In reality, students with the correct cultural ‘habitus,’ belonging to the family culture in the bourgeoisie and the upper class, have greater opportunities. These strata reproduce their privileged positions via the school system. The ideology of achievement as the basis for social mobility serves to veil the real process. Thus the school system does not pass on a society’s cultural heritage. Instead the culture of the ruling class makes primary use of it to maintain its privileged position.

3. The Dual Function Of Educational Systems In Modern Societies

Beyond a more affirmative or critical view on the social functions of educational systems in modern societies, the schooling process can be analyzed from two perspectives: one with the view on reproducing and changing society, the other on constituting individual qualifications and/orientations.

To see the social functions of ‘human processing’ via schools is indispensable for an adequate understanding of schooling. In a historical perspective, this becomes especially evident. From an individual perspective, school represents the most important cultural context for learning and the development of competencies and values. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the relationships between educational institutions and society can be characterized as follows:

(a) Reproduction of cultural systems, which are often characterized as knowledge and skills, is institutionalized within the school system. This involves mastering basic symbolic systems ranging from language and writing to acquiring specific professional qualifications. Accomplished by instruction, this function is referred to hereafter as the qualifying function. (b) The second function refers directly to the society’s social structure. Social structure is defined as the distribution of positions in the occupational and social area. By way of school-based learning of qualifications, verified by a detailed system of examinations, the young generation is allocated to stratified occupational positions (allocation and selection).

(c) School systems are instruments of social integration. Reproduction of norms, values, and belief systems serve to reinforce prevailing power relation- ships (see Bernstein 1996, for contemporary theory on the relationship between knowledge and control). This accounts for the central political function of the socialization process in educational institutions (integration and legitimization).

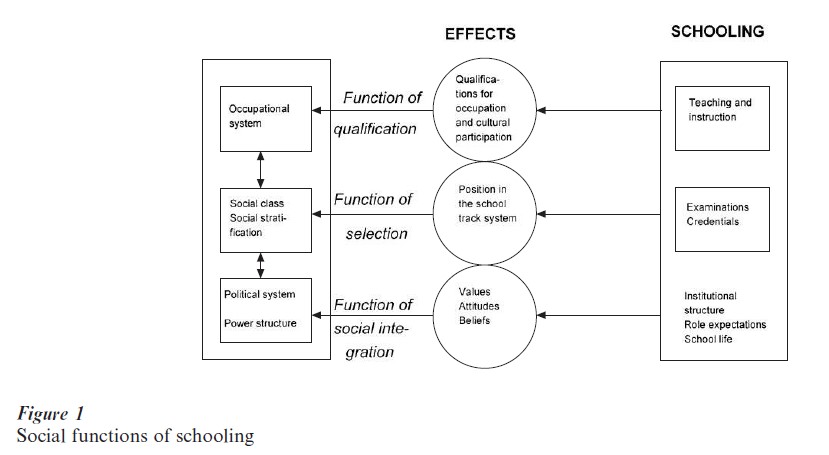

In Fig. 1, the three reproduction functions of educational systems in modern societies are summarized. They appear as contributions to a defined social system which are necessary for its survival. To those involved, functions appear as tasks and goals. Therefore, reproduction can be converted into social change via educational institutions.

The school’s societal references are shown on the left in Fig. 1. Systemic problems may arise which can only be solved adequately by educational institutions. This may be the case with regard to necessary qualification patterns for the occupational system, the legitimate structure of social mobility and social reproduction, and the legitimacy of the societal power structure or the political system.

The educational mechanisms through which societal problems are solved are shown on the right in Fig. 1. Instructional processes, examinations, and the institutional structure are differently involved in the process of fulfilling societal functions.

4. The Historic And Action-Theoretical Approach: The Evolution Of Relationships Between The Educational System And Society

From the background of the functional analysis above, the economic, social, and political significance of educational systems is clearly visible. At the same time it becomes evident that the functional relationships between educational institutions and society are at work only in modern societies. Because educational systems do not follow a path of social determinism, their historic evolution can be traced back to observable processes of their creation. They are the result of human agency and social interaction and thus distinguish themselves fundamentally from natural evolution, as do all other areas of social reality (Archer 1995).

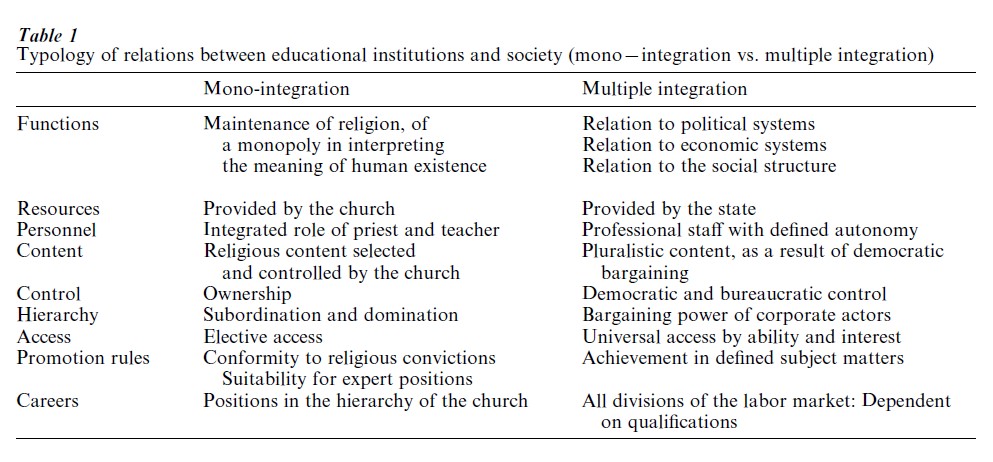

Educational systems in the European culture have emerged in the context of religious movements and interests. Until the eighteenth century it was the church, particularly, which provided personnel for schools, maintained buildings, selected curricula, set the definition for instruction and access to education, and shaped opportunities after graduation. In comparison to the multifunctional relationships between educational institutions and societies in modern times, this represented a case of mono-integration. The primary goal of educational institutions consisted in the cultural reproduction of religious knowledge and thereby maintained a monopoly in the Christian way of understanding human existence. As a book religion, Christianity depended on the training of religious experts. During the Reformation, providing direct access to the Bible became an essential part of the Christian way toward salvation. Therefore everybody should be able to read. This belief became an important impetus for teaching reading and writing to everybody. The practice of teaching was conceived along the lines of preaching and roles of teachers ran parallel to those of priests. Thus they determined the definition of knowledge in terms of pedagogical practice and the types and quality of educational output which seemed necessary.

Naturally, the typology in Table 1 fails to represent the total variety of historic phenomena covering educational institutions. There existed important national variations (see Archer 1979 for France, England, Russia, and Denmark) and particularly variations by religious faith. During the sixteenth century the Reformation was crucial for the emergence of alphabetization and literacy. It was also an important basis for the rise of national educational systems at the end of the eighteenth century.

In order to understand the emergence of national educational systems in European countries after the French Revolution, three historic predecessors have to be kept in mind: (a) it could build on advanced literacy (for Switzerland, see Messerli 1999), (b) there existed scholarly communities at universities since the middle ages, communicating in one common language (Latin), (c) private schools served the need for commercial and industrial qualifications in the cities. Accordingly, there had been scattered possibilities of education in the cities since antiquity. The universities represent a complex history in which the conflict between reason and faith arose early as a heritage of antiquity. Development of scientific thinking has been an important motivation for establishing public education since the Renaissance and the rise of humanism.

The rise of modern education became an essential part of the emergence of state structures from the nineteenth century onward. This process turned out to be a historic struggle for power in which identifiable actors and interest groups proceeded within the framework of historic and structural conditions. Their activities during a process of structural elaboration led to educational institutions, which only gradually assumed the characteristics of a coherent system in the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Speaking of an educational system means that pathways through the school system were systematically linked to each other, that a professionally trained staff emerged, and that coherent curricula were developed. During this process, the ‘meritocratic’ principle was established as the only legitimate way of promotion.

The three main social functions described above developed along this historic route. At the individual level they implied that long-term learning became a universal instrument of individual life planning. A parallel process could be observed at the social level. It implied the increasing inclusion of all social classes in the educational system. During the nineteenth century the struggle for social participation in education took place at the primary school level, in the twentieth century at the secondary and tertiary level. Thus discussion about the role of education reflects the political discourse of society. Yet it is embedded within the political rules of the society and the real power structure, which becomes visible in historic and comparative perspectives (see Heidenheimer 1997).

5. Empirical Analysis Of The Relationship Between The Educational System And Society

Historic analysis of the relationship between the educational system and society is not limited to the topic of how the educational system evolved parallel to and as part of the developing welfare state during the last two centuries.

5.1 Educational Expansion

Beyond system development, the factual educational participation at various educational levels can be described. Doing this, it becomes apparent that all parts of the population had become literate in most European nations toward the end of the nineteenth century. Expansion of secondary education and particularly tertiary schooling occurred cyclically, yet it was only during the 1950s that it began in large numbers. The sharp increase in educational participation from the 1950s to the 1970s began to level off from the 1980s.

Opinions vary greatly in the discussion of causes for this educational expansion. Doubt exists primarily about the thesis that it resulted from conscious planning and pressure by political decision makers. Actually it followed a complex interrelationship of supply and demand, of system-building processes on the supply side and accumulating consumer demand. Pressure from parents and students emerged in the twentieth century through perspectives on qualification-related life planning. These focused on the perception of opportunity structures influenced by economic developments in an era of rapid technological change and economic globalization. On the political level, a highly productive educational system turned out to be a key factor for successful global competition.

5.2 The Educational System And Social Structure

The nineteenth and twentieth centuries reflect the struggle over participation in education by privileged and disadvantaged social groups. Efforts were exerted to achieve a classless society by education, by implementing the principle of meritocracy, and by forcing the nobility to take examinations. Educational expansion brought about egalitarian effects and strengthened the role of the equal rights of all citizens (Muller 1998). Moreover, parallel to expansion the twentieth century saw an observable increase in educational opportunities for the farming sector as well as for workers and employees. Yet relative inequality of opportunity (Fend 1982) still existed in all industrialized nations at the end of the twentieth century.

The greatest progress in educational participation during the second half of the twentieth century could be observed among girls and women. They profited most from educational expansion (Blossfeld and Shavit 1993, Dahrendorf 1965, Muller and Karle 1993, Schimpl-Neimanns and Luttinger 1993).

6. Practical Questions

Linking a theory of educational institutions to historical processes of their creation opens up the perspective that humans are responsible for shaping educational institutions for the demands of future developments. Questions of quality in the educational systems and their effectiveness in the light of limited resources have top priority in the political agenda. At the opening of the twenty-first century one central issue deals with the problem of how to shape the qualifying function of educational institutions within the framework of international economic competition. Answers to questions about equal opportunity and the principle of meritocracy will shape the acceptance of education in the coming years. Questions concerning democratic control of knowledge and values will be of great significance for the peaceful coexistence of people in a global civil society.

Bibliography:

- Apple M W 1999 Power, Meaning, and Identity. Peter Lang, New York

- Archer M S 1979 Social Origins of Educational Systems. Sage, London

- Archer M S 1995 Realist Social Theory: The Morphogetic Approach. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Bernstein B B 1996 Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity. Theory, Research, Critique. Taylor and Francis, London

- Blossfeld H-P, Shavit Y 1993 Dauerhafte Ungleichheiten. Zur Veranderung des Einflusses der sozialen Herkunft auf die Bildungschancen in dreizehn industrialisierten Landern. Zeitschrift fur Padagogik 39(1): 25–52

- Bourdieu P, Passeron J-C 1977 Reproduction in Education, Society, and Culture. Sage, London

- Dahrendorf R 1965 Bildung ist Burgerrecht. Pladoyer fur eine aktive Bildungspolitik. Nannen-Verlag, Hamburg, Germany

- Dreeben R 1968 On What is Learned in School. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA

- Durkheim E 1956 Sociology and Education. Free Press, Glencoe, IL

- Fend H 1982 Gesamtschule im Vergleich. Beltz, Weinheim, Germany

- Halsey A H 1973 The sociology of education. In: Smelser N J (ed.) Sociology. An Introduction. New York, Wiley, pp. 381–434

- Heidenheimer A J 1997 Disparate Ladders. Why School and University Policies Differ in Germany, Japan and Switzerland. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, NJ

- Messerli A 1999 Lesen und Schreiben 1700 bis 1900 Unpublished postdoctoral dissertation, University of Zurich, Switzerland

- Muller W 1998 Erwartete und unerwartete Folgen der Bildungsexpansion. In: Friedrichs J, Lepsius M R, Mayer K U (eds.) Die Diagnosefahigkeit der Soziologie. Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen, Germany, pp. 81–112

- Muller W, Karle W 1993 Social selection in educational systems in Europe. European Sociological Review 9(1): 1–23

- Parsons T 1959 The school class as a social system: Some of its functions in the American society. Harvard Educational Review 29(4): 297–318

- Schimpl-Neimanns B, Luttinger P 1993 Die Entwicklung bildungsspezifischer Ungleichheit: Bildungsforschung mit Daten der amtlichen Statistik. Zuma Nachrichten 32: 76–115