Sample Distance Education Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

1. History: From Correspondence Education To Distance Education

The beginning of what today we call ‘distance education’ is to be found in the concept of correspondence courses starting in the middle of the nineteenth century, with surface-mail corrections of assignments in, for example, shorthand courses or language learning courses. Printed material as instructional provision was enriched by tutorial interaction via the mail.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The university extension movement, which enabled students in the colonies to prepare for a final examination, is another root of distance education. Elements such as written assignments and corrections, as well as instructions following the prescribed curriculum of an institution, could be more and more elaborated and diversified as the quality and ease of mail services all over the world developed.

Wherever the mail service was unreliable or wherever socialization processes were predominant, alternative forms of higher education evolved. An example is the former USSR, where until the middle of the twentieth century correspondence education was developed as a special form of higher education for the workforce, with personal contacts, seminars, and examinations offered on the premises of classical education institutions at times when the regular students were on vacation (e.g., in summer periods). Adult education with evening courses and correspondence education with vacation courses increased the efficiency of higher-education institutions: more than one-third of all higher-education examinations in the former USSR came from this kind of correspondence education.

There is also a tradition of distance education in rural regions (where geographic distances have to be overcome) and even for secondary schooling, for example in Australia. Some governments provide their staff and families with opportunities for distance education during stays abroad. During World War II, for example, the US government had a large department of distance education for the military.

As basic communication systems gradually changed in the middle of the twentieth century from surface mail to electronic systems, a gradual change from correspondence education to distance education took place. There was more and more dependency on the efficiency of modern media, leading to today’s situation, in which even final examinations in some universities may take place as video conferences.

2. Definition

Distance education is an organizational form of education in which instructional provisions, tutorial interactions, monitoring of practice, as well as individual control of learning may take place via media which make the simultaneous personal presence of tutors and students avoidable.

3. Theory

The characteristic feature of distance education is the planned and controlled two-way interaction which differentiates it from all self-instructional methods. For a long time distance education was regarded as an inferior form of higher education, lacking all the possibilities of socializing students in an academic tradition.

Meanwhile the large institutions for distance education increase their leading role in national highereducation provision. Sir John Daniel (1996) of the British Open University speaks of ‘mega-universities’ regularly enrolling more than 100,000 students a year. In Europe at the end of the twentieth century more than 2.2 million students were enrolled in formal systems of distance education—in France alone the Centre National d’Education a Distance, founded in 1939, offers distance education as a form of continuing education for the public services to more than 400,000 students. With the decline of government-controlled higher education in the former socialist regions of Europe, there is also a growing ‘private market’ selling distance education courses to half a million people in Eastern European countries. Enrolments of more than 100,000 students each year are also reported from China and Korea.

The above-mentioned sense of distance education as inferior is fading away not only because of its success in terms of enrolment numbers but also because of the insight that the processes of planning or better ‘designing’ instruction, foreseeing instances for communication, including regular assessment possibilities for self-paced learning, and the necessity for constant quality control all have a long tradition in distance education and are seen to be the key factors of modern higher education.

3.1 Dropout Rates

One of the major problems of all distance education institutions is the fact that they have to report dropout rates of mostly more than 50 percent. The reason for such dropout figures is the heterogeneity of the students attracted by this form of higher education.

Many students drop out because they:

(a) just want to own course material for reference to keep up with the development in their subject area (nonstarter);

(b) try to work through the material and decide that the course does not meet their expectations (draw- back);

(c) worked through the material, participating in regular assessment, but stopped when saturated (drop- out); or

(d) worked through the whole course but decided not to sit for an examination (no-show).

It is clear that for adult learners none of these decisions can be associated easily with academic failure. Only in one of the categories, whenever ‘dropout’ students fail to meet their own goals, can we speak of ‘dropout’ in the usual sense of failure. Therefore the dropout rates do not give information about the didactic quality of the program but rather about bureaucratic problems of handling different types of customers with different types of interests.

3.2 Microdidactics For Megasystems

For a long time educational systems have been organized as representing a static concept of learning. Curricula with a plethora of old and new elements recommended as being useful for life or jobs were prescribed for young people—with initiation rites at the end of schooling (Vertecchi 1998). The clearer it became that learning will never end in one’s lifetime, the faster and more regularly industry and changing administrations needed new qualifications, the faster educational systems had to adapt to these changing scenarios. One of these modern scenarios is distance education. In the middle of the twentieth century the striking analogy between distance education and the processes and pitfalls of early industrialization was presented by Peters (1983), who coined the expression ‘DE as an industrialized form of teaching and learning,’ mass production and specialization of the workforce in the production process being the characteristic features of large distance-education institutions. This subsequently led to the discussion of Fordism and labour-market theories in distance education (Rumble 1995). At the turn of the millennium observations in so-called virtual seminars led back to the micro-didactic features of distance education in proving that characteristics of school learning would also take place in virtual settings (Fritsch 1997).

The discussions of quality control in the field of education at the turn of the twenty-first century showed that distance education institutions are much more at ease with the requirement of institutional evaluation than traditional institutions, where didactical situations are beyond control of the management because the door of the classroom is usually closed.

3.3 Media As Method

The didactic dimensions of the field of education are also valid for modern higher education using modern media:

(a) The pitfalls of misunderstanding media can easily be traced to the assumption that some areas of interest (content and goals) are easier to transmit via modern media than others.

(b) Media for instruction, especially increasing the number of possible students by mass production of teaching material (and thus the functions and characteristics of teachers), are the reason why distance education has suffered from an inferiority complex: virtual teaching situations are considered less valid than real world ones.

(c) There is a misunderstanding that media must be a separate element (what is the most convenient way of doing this?) in the dimensions of education. In fact, it is the method of teaching which forms this element, not the media. Consequently the didactic field has not changed in its basic structure.

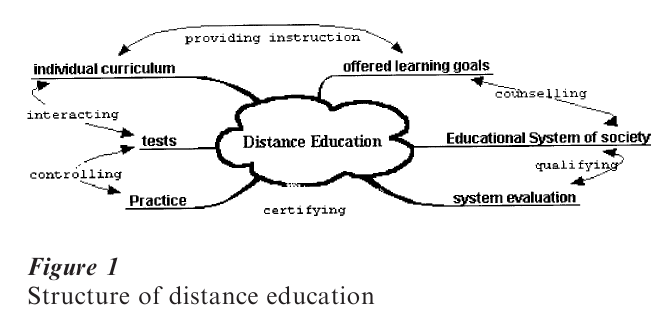

Where media have a role to play in all fields is with regard to the question of interactions between didactic functions: ‘qualifying, counselling, instructing, interacting, controlling and certifying.’ Many interactions between didactic elements (see Fig. 1)—goals–content, teacher–student, and practice–society—can also be realized using modern media. ‘Non-contiguous forms’ (Holmberg 1989) of interaction (transcending the limitations of time and place) in the educational process are in the foreground of distance-education theory.

For example: whenever a university uses campus TV or satellite TV to ‘broaden’ the scope of its audience, this should not yet be called distance education because the didactical setup remains dependent upon the simultaneous presence of student and teacher at defined places. Instead, this setup belongs to the concept of ‘distributed learning’ (Bates 1995). However, when a ‘lecture’ is integrated (e.g., as a video) into a defined setting of didactical considerations it might very well be part of a distance education program, because the necessity for individuals to attend a certain place simultaneously is no longer a given. This argument does not mean that distance education will never provide face-to-face contact: most distance-education organizations do have provisions for social interaction or tutorial help. The question is which predefined didactical function can be best met by which medium.

3.4 Error-Oriented Tutoring

Mass production of teaching material on the one hand is counterbalanced by the need to tutor large numbers of students on the other—as long as tutoring and individual help are carried out in the same way as in regular educational settings, distance education will not have a big economic effect on educational systems. But the possibility of designing tutorial help, via modern media, to include systems of automatic tutorial help makes distance education economically much more efficient. In classroom situations teachers know there are certain points in the learning process at which students always have similar difficulties. Good teachers not only indicate that an error has been made, but give assistance in the form of explanations, additional assignments, etc. Such error-oriented comments, explanations, and additional assignments can be geared automatically to the student exactly when an error occurs—just in time. In the early days of distance education the Open University, for example, had two different forms of assignments: tutor-marked assignments (TMA) and computer-marked assignments (CMA). It is more costly to have many TMAs and the turnaround time of CMAs can be far more effective (even more so if transferred to the World Wide Web for instant control). Fern University at Hagen, Germany, has developed a system of CMAs which provide the student with comments on typical errors made. Empirical research has shown that a very high percentage of previewable errors can be handled in this way. In projects of language learning, too, instant correction of previewed errors has proven to be a very important didactical feature in the use of modern media.

3.5 Transformation

In many cases concentrating on the element of instructional provision and transforming it into modern media is misunderstood as a way of attempting to transform the whole system of education, and neglecting other elements of teaching (tutorial interactions, monitoring of practice, and individual control of learning).

It is much easier to transfer existing courses of distance education to the World Wide Web, if they have been prepared in a way that is typical for high-quality education of this type, with:

(a) learning goals explicitly formulated;

(b) structured curriculum decisions according to individual interests;

(c) instances for monitored practice and tutorial help;

(d) control of learning outcomes; and

(e) evaluation of the system of teaching and learning.

4. State Of The Art

Many large universities have found a new market in courses for continuing education and have installed departments for distance education, especially because of the need to cater for students who belong to the regular workforce or live far away and cannot be asked to come to campus for lectures or seminars. These universities are called ‘dual-mode universities’ because their academic position in the hierarchy of higher-education institutions has been thought to depend on the classical structure of also being a ‘regular’ university. Even the earliest forms of distance education institutions, such as the University of South Africa, are regarded as dual-mode universities. It was the British Open University which was the first to enter the higher-education sector as a purely single-mode distance-education university, and it has influenced the development of dozens of other universities worldwide. It is the impact of new technologies on both systems, traditional and distance education, which is forcing higher-education institutions to think about their specific potential. The distinction between campus-based and distance learning becomes more and more irrelevant as both learner groups use modes of distributed teaching. Asynchronous communicative acts for learning are no longer specific to the distance education sector. The boundaries of campus have lost their relevance with the advent of the World Wide Web. Whether distance education will survive in future depends on whether classical higher-education institutions are prepared to enter into a continuous dialog with each individual learner.

5. Distance Education Institutions De Eloping Into Virtual Universities

There has been an explosion of distance-education courses made available through the Web—at the end of the 1990s linked Web descriptions of more than 15,000 different courses could be traced— and this comprises just the major institutions of English-speaking countries, which have a longer tradition in distance education. Global universities (http://www.global-learning.de/g-learn aktuell/index.html), Globewide Network Academy (http://www.gnacademy.org), and World Lecture Hall (http://www.utexas.edu/world/lecture) are the main addresses of these initiatives. This booming advance has been made possible by the fact that customers want to know what they will ‘get’ for their participation, and internationally accepted credits are the key to this development. Without a functioning credit transfer system like the one students are familiar with in the USA, this development will halt at the borders of traditional tertiary education. As a result the development of a European Credit Transfer System has become a major topic in the European Union. But the time that elapses before such a European-wide system is introduced and accepted will show that this form of education is big business; people interested in continuing education are more interested in ‘just-in-time’ courses, taken when they need them, than in following a prescribed curriculum. Consequently, one of the goals of the International Council for Distance Education (ICDE), the worldwide association of major institutions acknowledged by UNESCO, which runs biannual conferences (http://www.icde.org), is to provide databases with information about all the courses available. This goal is also being pursued by the International Centre for Distance Learning (ICDL) at the Open University in Milton Keynes, which has produced a structured Bibliography: of distance learning (http://www.icdl./open.ac.uk/bib/toc.htm).

Bibliography:

- Bates A W 1995 Technology, Open Learning and Distance Education. Routledge, London

- Daniel J 1996 The Mega-Universities and the Knowledge Media. Kogan Page, London

- Fritsch H 1997 Witness-learning: Pedagogical implications of net-based teaching and learning. Staff and Educational Development International 1: 107–28

- Holmberg B 1989 Theory and Practice of Distance Education. Routledge, London, New York

- Keegan D 1996 Foundations of Distance Education, 3rd edn. Routledge, London, New York

- Peters O 1983 Distance education and industrial production: A comparative interpretation in outline. In: Sewart D, Keegan D, Holmberg B (eds.) Distance Education: International Perspectives. Croom Helm Routledge, London, pp. 95–113

- Rumble G 1995 Labour market theories and distance education I: Industrialisation and distance education. Open Learning 10: 10–20

- Vertecchi B 1998 Elementeveiner Theorie des Fernunterrichts. ZIFF Papiere 109. FernUniversitat, Hagen, Germany