Sample Mood, Cognition, and Memory Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Recent years have witnessed a mounting interest in the impact of happiness, sadness, and other affective states or moods on learning, memory, decision making, and allied cognitive processes. Much of this interest has focused on two phenomena: mood-congruent cognition, the observation that a given mood promotes the processing of information that possesses a similar affective tone or valence, and mooddependent memory, the observation that information encoded in a particular mood is most retrievable in that mood, irrespective of the information’s affective valence. This research paper examines the history and current status of research on mood congruence and mood dependence with a view to clarifying what is known about each of these phenomena and why they are both worth knowing about.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Mood Congruence

The interplay between feeling and thinking, affect and cognition, has been a subject of scholarly discussion and spirited debate since antiquity. From Plato to Pascal, a long line of Western philosophers have proposed that “passions” have a potentially dangerous, invasive influence on rational thinking, an idea that re-emerged in Freud’s psychodynamic theories. However, recent advances in cognitive psychology and neuroscience have promoted the radically different view that affect is often a useful and even essential component of adaptive social thinking (Adolphs & Damasio, 2001; Cosmides & Tooby, 2000).

The research to be reviewed in this section shows that affective states often produce powerful assimilative or congruent effects on the way people acquire, remember, and interpret information. However, we will also see that these effects are not universal, but depend on a variety of situational and contextual variables that recruit different information-processing strategies. Accordingly, one of the main aims of modern research, and of this review, is to clarify why mood-congruent effects emerge under certain circumstances but not others.

To this end, we begin by recapping two early theoretical perspectives on mood congruence (one based on psychoanalytic constructs, the other on principles of conditioning) and then turn to two more recent accounts (affect priming and affect-as-information). Next, we outline an integrative theory that is designed to explain the different ways in which affect can have an impact on cognition in general, and social cognition in particular. Finally, empirical evidence is examined which elucidates the essential role that different processing strategies play in the occurrence—or nonoccurrence—of mood congruence.

Early Theories of Mood Congruence

Philosophers, politicians, and playwrights alike have recognized for centuries the capacity of moods to color the way people remember the past, experience the present, and forecast the future. Psychologists, however, were relatively late to acknowledge this reality, despite a number of promising early leads (e.g., Rapaport, 1942/1961; Razran, 1940). Indeed, it is only within the past 25 years that empirical investigations of the interplay between affect and cognition have been published with regularity in mainstream psychology journals (see LeDoux, 1996).

Psychology’s late start in exploring the affect-cognition interface reflects the fact that neither behaviorism nor cognitivism—the two paradigms that dominated the discipline throughout the twentieth century—ascribed much importance to affective phenomena, whether in the form of specific, short-lived emotional reactions or more nebulous, long-lasting mood states (for detailed discussion of affectrelated concepts, see Russell & Feldman Barrett, 1999; Russell & Lemay, 2000).

From the perspective of the radical behaviorist, all unobservable mental events, including those affective in nature, were by definition deemed beyond the bounds of scientific psychology. Although early behaviorist research examined the environmental conditioning of emotional responses (an issue taken up later in this research paper), later studies focused mainly on the behavioral consequences of readily manipulated drive states, such as thirst or fear. In such studies, emotion was instilled in animals through crude if effective means, such as electric shock, and so-called emotionality was operationalized by counting the number of faecal boli deposited by small, scared animals. As a result, behaviorist research and theory added little to our understanding of the interrelations between affect and cognition.

Until recently, the alternative cognitive paradigm also had little interest in affective phenomena. To the extent that the cognitive revolutionaries of the early 1960s considered affects at all, they typically envisaged them as disruptive influences on proper—read emotionless or cold—thought processes. Thus, the transition from behaviorism to cognitivism allowed psychology to reclaim its head, but did nothing to recapture its heart.

Things are different today. Affect is now known to play a critical role in how information about the world is processed and represented. Moreover, affect underlies the cognitive representation of social experience (Forgas, 1979), and emotional responses can serve as an organizing principle in cognitive categorization (Niedenthal & Halberstadt, 2000). Thus, the experience of affect—how we feel about people, places, and events—plays a pivotal role in people’s cognitive representations of themselves and the world around them.

Affect also has a more dynamic role in information processing. In a classic series of studies, Razran (1940) showed thatsubjectsevaluatedsociopoliticalmessagesmorefavorably when in a good than in a bad mood. Far ahead of their time, Razran’s studies, and those reported by other investigators (e.g.,Bousfield,1950),providedthefirstempiricalevidenceof mood congruence, and their results were initially explained in terms of either psychodynamic or associationist principles.

Psychodynamic Account

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory suggested that affect has a dynamic, invasive quality that can infuse thinking and judgments unless adequately controlled. A pioneering study by Feshbach and Singer (1957) tested the psychodynamic prediction that attempts to suppress affect should increase the “pressure” for affect infusion. They induced fear in their subjects through electric shocks and then instructed some of them to suppress their fear. Fearful subjects’thoughts about another person showed greater mood congruence, so that they perceived the other person as being especially anxious. Interestingly, indeed ironically (Wegner, 1994), this effect was even greater when subjects were trying to suppress their fear. Feshbach and Singer (1957) explained this in terms of projection and proposed that “suppression of fear facilitates the tendency to project fear onto another social object” (p. 286).

Conditioning Account

Although radical behaviorism outlawed the study of subjective experiences, including affects, conditioning theories did nevertheless have an important influence on research. Watson’s work with Little Albert was among the first to find affect congruence in conditioned responses (Watson, 1929; Watson & Rayner, 1920). This work showed that reactions toward a previously neutral stimulus, such as a furry rabbit, could become affectively loaded after an association had been established between the rabbit and fear-arousing stimuli, such as a loud noise. Watson thought that most complex affective reactions acquired throughout life areestablished as a result of just such cumulative patterns of incidental associations.

The conditioning approach was subsequently used by Byrne and Clore (1970; Clore & Byrne, 1974) to explore affective influences on interpersonal attitudes. These researchers argued that aversive environments (as unconditioned stimuli) spontaneously produce negative affective reactions (as unconditioned responses). When another person is encountered in an aversive environment (the conditioned stimulus), the affective reaction it evokes will become associated with the new target (a conditioned response). Several studies, published in the 1970s, supported this reasoning (e.g., Gouaux, 1971; Gouaux & Summers, 1973; Griffitt, 1970). More recently, Berkowitz and his colleagues (Berkowitz, Jaffee, Jo, & Troccoli, 2000) have suggested that these early associationist ideas remain a powerful influence on current theorizing, as we shall see later.

Contemporary Cognitive Theories

Although affective states often infuse cognition, as several early experiments showed, neither the psychoanalytic nor the conditioning accounts offered a convincing explanation of the psychological mechanisms involved. In contrast, contemporary cognitive theories seek to specify the precise information-processing mechanisms responsible for these effects.

Two types of cognitive theories have been proposed to account for mood congruence: memory-based theories (e.g., the affect priming model; see Bower & Forgas, 2000), and inferential theories (e.g., the affect-as-information model; see Clore, Gasper, & Garvin, 2001). Whereas both of these accounts are chiefly concerned with the impact of moods on the content of cognition (or what people think), a third type of theory focuses on the processing consequences of affect (or how people think). These three theoretical frameworks are sketched in the following sections.

Memory-Based Accounts

Several cognitive theories suggest that moods exert a congruent influence on the content of cognition because they influence the memory structures people rely on when processing information. For example, Wyer and Srull’s (1989) storagebin model suggests that recently activated concepts are more accessible because such concepts are returned to the top of mental “storage bins.” Subsequent sequential search for interpretive information is more likely to access the same concepts again. As affective states facilitate the use of positively or negatively valenced mental concepts, this could account for the greater use of mood-congruent constructs in subsequent tasks.

A more comprehensive explanation of this effect was outlined in the associative network model proposed by Bower (1981). In this view, the observed links between affect and thinking are neither motivationally based, as psychodynamic theories suggest, nor are they the result of merely incidental, blind associations, as conditioning theories imply. Instead, Bower (1981) argued that affect is integrally linked to an associative network of mental representations. The activation of an affective state should thus selectively and automatically prime associated thoughts and representations previously linked to that affect, and these concepts should be more likely to be used in subsequent constructive cognitive tasks. Consistent with the network model, early studies provided strong support for the concept of affective priming, indicating mood congruence across a broad spectrum of cognitive tasks. For example, people induced to feel good or bad tend to selectively remember more mood-congruent details from their childhood and more of the real-life events they had recorded in diaries for the past few weeks (Bower, 1981). Mood congruence was also observed in subjects’ interpretations of social behaviors (Forgas, Bower, & Krantz, 1984) and in their impressions of other people (Forgas & Bower, 1987).

However, subsequent research showed that mood congruence is subject to several boundary conditions (see Blaney, 1986; Bower, 1987; Singer & Salovey, 1988). Problems in obtaining reliable mood-congruent effects were variously explained as due to (a) the lack of sufficiently strong or intense moods (Bower & Mayer, 1985); (b) the subjects’ inability to perceive a meaningful, causal connection between their current mood and the cognitive task they are asked to perform (Bower, 1991); and (c) the use of tasks that prevent subjects from processing the target material in a self-referential manner (Blaney, 1986). Interestingly, mood-congruent effects tend to be more reliably obtained when complex and realistic stimuli are used. Thus, such effects have been most consistently demonstrated in tasks that require a high degree of open, constructive processing, such as inferences, associations, impression formation, and interpersonal behaviors (e.g., Bower & Forgas, 2000; Mayer, Gaschke, Braverman, & Evans, 1992; Salovey, Detweiler, Steward, & Bedell, 2001). Such tasks provide people with a rich set of encoding and retrieval cues, and thus allow affect to more readily function as a differentiating context (Bower, 1992).

A similar point was made by Fiedler (1991), who suggested that mood congruence is apt to occur only in constructive cognitive tasks, those that involve an open-ended search for information (as in recall tasks) and the active elaboration and transformation of stimulus details using existing knowledge structures(asinjudgmentalandinferentialtasks).Bycontrast, tasks that do not place a premium on constructive processing, such as those requiring the simple recognition of familiar words or the reflexive reproduction of preexisting attitudes, afford little opportunity to use affectively primed information and thus tend to be impervious to mood effects.

It appears, then, that affect priming occurs when an existing affective state preferentially activates and facilitates the use of affect-consistent information from memory in a constructive cognitive task. The consequence of affect priming is affect infusion: the tendency for judgments, memories, thoughts, and behaviors to become more mood congruent (Forgas, 1995). However, in order for such infusion effects to occur, it is necessary for people to adopt an open, elaborate information-processing strategy that facilitates the incidental use of affectively primed memories and information. Thus, the nature and extent of affective influences on cognition should largely depend on what kind of informationprocessing strategy people employ in a particular situation. Later we will review the empirical evidence for this prediction and describe an integrative theory that emphasizes the role of information-processing strategies in moderating mood congruence.

Inferential Accounts

Several theorists maintain that many manifestations of mood congruence can be readily explained in terms other than affect priming. Chief among these alternative accounts is the affect-as-information (AAI) model advanced by Schwarz and Clore (1983, 1988). This model suggests that “rather than computing a judgment on the basis of recalled features of a target, individuals may . . . ask themselves: ‘how do I feel about it? [and] in doing so, they may mistake feelings due to a pre-existing [sic] state as a reaction to the target” (Schwarz, 1990, p. 529). Thus, the model implies that mood congruence in judgments is due to an inferential error, as people misattribute a preexisting affective state to a judgmental target.

The AAI model incorporates ideas from at least three past research traditions. First, the predictions of the model are often indistinguishable from earlier conditioning research by Clore and Byrne (1974). Whereas the conditioning account emphasized blind temporal and spatial contiguity as responsible for linking affect to judgments, the AAI model, rather less parsimoniously, posits an internal inferential process as producing the same effects (see Berkowitz et al., 2000). A second tradition that informs theAAI model comes from research on misattribution, according to which judgments are often inferred on the basis of salient but irrele vant cues:in this case, affective state. Thus, the AAI model also predicts that only previously unattributed affect canproduce mood congruence. Finally, the model also shows some affinity with research on judgmental heuristics, in the sense that affective states are thought to function as heuristic cues in informing people’s judgments.

Again, these effects are not universal. Typically, people rely on affect as a heuristic cue only when “the task is of little personal relevance, when little other information is available, when problems are too complex to be solved systematically, and when time or attentional resources are limited” (Fiedler, 2001, p. 175). For example, some of the earliest and still most compelling evidence for the AAI model came from an experiment (Schwarz & Clore, 1983) that involved telephoning respondents and asking them unexpected and unfamiliar questions. In this situation, subjects have little personal interest or involvement in responding to a stranger, and they have neither the motivation, time, nor cognitive resources to engage in extensive processing. Relying on prevailing affect to infer a response seems a reasonable strategy under such circumstances. In a different but related case, Forgas and Moylan (1987) asked almost 1,000 people to complete an attitude survey on the sidewalk outside a cinema in which they had just watched either a happy or a sad film. The results showed strong mood congruence: Happy theatergoers gave much more positive responses than did their sad counterparts. In this situation, as in the study by Schwarz and Clore (1983), respondents presumably had little time, motivation, or capacity to engage in elaborate processing, and hence they may well have relied on their temporary affect as a heuristic cue to infer a reaction.

On the negative side, the AAI model has some serious shortcomings. First, although the model is applicable to mood congruence in evaluative judgments, it has difficulty accounting for the infusion of affect into other cognitive processes, including attention, learning, and memory. Also, it is sometimes claimed (e.g., Clore et al., 2001; Schwarz & Clore, 1988) that the model is supported by the finding that mood congruence can be eliminated by calling the subjects’ attention to the true source of their mood, thereby minimizing the possibility of an affect misattribution. This claim is dubious, as we know that mood congruence due to affect-priming mechanisms can similarly be reversed by instructing subjects to focus on their internal states (Berkowitz et al., 2000). Moreover, Martin (2000) has argued that the informational value of affective states cannot be regarded as “given” and permanent, but instead depends on the situational context. Thus, positive affect may signal that a positive response is appropriate if the setting happens to be, say, a wedding, but the same mood may have a different meaning at a funeral. The AAI model also has nothing to say about how cues other than affect (such as memories, features of the stimulus, etc.) can enter into a judgment. In that sense, AAI is really a theory of nonjudgment or aborted judgment, rather than a theory of judgment. It now appears that in most realistic cognitive tasks, affect priming rather than the affect-as-information is the main mechanism producing mood congruence.

Processing Consequences of Moods

In addition to influencing what people think, moods may also influence the process of cognition, that is, how people think. It has been suggested that positive affect recruits less effortful and more superficial processing strategies; in contrast, negative affect seems to trigger a more analytic and vigilant processing style (Clark & Isen, 1982; Mackie & Worth, 1991; Schwarz, 1990). However, more recent studies have shown that positive affect can also produce distinct processing advantages: Happy people often adopt more creative and inclusive thinking styles, and display greater mental flexibility, than do sad subjects (Bless, 2000; Fiedler, 2000).

Several theories have been advanced to explain affective influences on processing strategies. One suggestion is that the experience of a negative mood, or any affective state, gives rise to intrusive, irrelevant thoughts that deplete attentional resources, and in turn lead to poor performance in a variety of cognitive tasks (Ellis & Ashbrook, 1988; Ellis & Moore, 1999). An alternative account points to the motivational consequences of positive and negative affect. According to this view (Isen, 1984), people experiencing positive affect may try to maintain a pleasant state by refraining from any effortful activity. In contrast, negative affect may motivate people to engage in vigilant, effortful processing. In a variation of this idea, Schwarz (1990) has suggested that affects have a signaling or tuning function, informing the person that relaxed, effort-minimizing processing is appropriate in the case of positive affect, whereas vigilant, effortful processing is best suited for negative affect.

These various arguments all assume that positive and negative affect decrease or increase the effort, vigilance, and elaborateness of information processing, albeit for different reasons. More recently, both Bless (2000) and Fiedler (2000) have conjectured that the evolutionary significance of positive and negative affect is not simply to influence processing effort, but to trigger two fundamentally different processing styles. They suggest that positive affect promotes a more schema-based, top-down, assimilative processing style, whereas negative affect produces a more bottom-up, externally focused, accommodative processing strategy. These strategies can be equally vigilant and effortful, yet they produce markedly different cognitive outcomes by directing attention to internal or external sources of information.

Toward an Integrative Theory: The Affect Infusion Model

As this short review shows, affective states have clear if complex effects on both the substance of cognition (i.e., the contents of one’s thoughts) and its style (e.g., whether information is processed systematically or superficially). It is also clear, however, that affective influences on cognition are highly context specific. A comprehensive explanation of these effects needs to specify the circumstances that abet or impede mood congruence, and it should also define the conditions likely to trigger either affect priming or affectas-information mechanisms.

The affect infusion model or AIM (Forgas, 1995) seeks to accomplish these goals by expanding on Fiedler’s (1991) idea that mood congruence is most likely to occur when circumstances call for an open, constructive style of information processing. Such a style involves the active elaboration of the available stimulus details and the use of memory-based information in this process. The AIM thus predicts that (a) the extent and nature of affect infusion should be dependent on the kind of processing strategy that is used, and (b) all things being equal, people should use the least effortful and simplest processing strategy capable of producing a response. As this model has been described in detail elsewhere (Forgas, 1995), only a brief overview will be included here.

The AIM identifies four processing strategies that vary according to both the degree of openness or constructiveness of the information-search strategy and the amount of effort exerted in seeking a solution. The direct access strategy involves the retrieval of preexisting responses and is most likely when the task is highly familiar and when no strong situational or motivational cues call for more elaborate processing. For example, if you were asked to make an evaluative judgment about a well-known political leader, a previously computed and stored response would come quickly and effortlessly to mind, assuming that you had thought about this topic extensively in the past. People possess a rich store of such preformed attitudes and judgments. Given that such standard responses require no constructive processing, affect infusion should not occur.

The motivated processing strategy involves highly selective and targeted thinking that is dominated by a particular motivational objective. This strategy also precludes open information search and should be impervious to affect infusion (Clark & Isen, 1982). For example, if in a job interview you are asked about your attitude toward the company you want to join, the response will be dominated by the motivation to produce an acceptable response. Open, constructive processing is inhibited, and affect infusion is unlikely to occur. However, the consequences of motivated processing may be more complex and, depending on the particular processing goal, may also produce a reversal of mood-congruent effects (Berkowitz et al., 2000; Forgas, 1991; Forgas & Fiedler, 1996). Recent theories, such as as Martin’s (2000) configural model, go some way toward accounting for these contextspecific influences.

The remaining two processing strategies require more constructive and open-ended information search strategies, and thus they facilitate affect infusion. Heuristic processing is most likely when the task is simple, familiar, of little personal relevance, and cognitive capacity is limited and there are no motivational or situational pressures for more detailed processing. This is the kind of superficial, quick processing style people are likely adopt when they are asked to respond to unexpected questions in a telephone survey (Schwarz & Clore, 1983) or are asked to reply to a street survey (Forgas & Moylan, 1987). Heuristic processing can lead to affect infusion as long as people rely on affect as a simple inferential cue and depend on the “how do I feel about it” heuristic to produce a response (Clore et al., 2001; Schwarz & Clore, 1988).

When simpler strategies such as direct access or motivated processing prove inadequate, people need to engage in substantive processing to satisfy the demands of the task at hand. Substantive processing requires individuals to select and interpret novel information and relate this information to their preexisting, memory-based knowledge structures in order to compute and produce a response. This is the kind of strategy an individual might apply when thinking about interpersonal conflicts or when deciding how to make a problematic request (Forgas, 1994, 1999a, 1999b).

Substantive processing should be adopted when (a) the task is in some ways demanding, atypical, complex, novel, or personally relevant; (b) there are no direct-access responses available; (c) there are no clear motivational goals to guide processing; and (d) adequate time and other processing resources are available. Substantive processing is an inherently open and constructive strategy, and affect may selectively prime or enhance the accessibility of related thoughts, memories, and interpretations. The AIM makes the interesting and counterintuitive prediction that affect infusion—and hence mood congruence—should be increased when extensive and elaborate processing is required to deal with a more complex, demanding, or novel task. This prediction has been borne out by several studies that we will soon review.

The AIM also specifies a range of contextual variables related to the task, the person, and the situation that jointly influence processing choices. For example, greater task familiarity, complexity, and typicality should recruit more substantive processing. Personal characteristics that influence processing style include motivation, cognitive capacity, and personality traits such as self-esteem (Rusting, 2001; Smith & Petty, 1995). Situational factors that influence processing style include social norms, public scrutiny, and social influence by others (Forgas, 1990).

An important feature of the AIM is that it recognizes that affect itself can also influence processing choices. As noted earlier, both Bless (2000) and Fiedler (2000) have proposed that positive affect typically generates a more top-down, schema-driven processing style whereby new information is assimilated into what is already known. In contrast, negative affect often promotes a more piecemeal, bottom-up processing strategy in which attention to external events dominates over existing stored knowledge.

The key prediction of the AIM is the absence of affect infusion when direct access or motivated processing is used, and the presence of affect infusion during heuristic and substantive processing. The implications of this model have now been supported in a number of the experiments considered in following sections.

Evidence Relating Processing Strategies to Mood Congruence

This section will review a number of empirical studies that illustrate the multiple roles of affect in cognition, focusing on several substantive areas in which mood congruence has been demonstrated, including affective influences on learning, memory, perceptions, judgments, and inferences.

Mood Congruence in Attention and Learning

Many everyday cognitive tasks are performed under conditions of considerable information overload, when people need to select a small sample of information for further processing. Affect may have a significant influence on what people will pay attention to and learn (Niedenthal & Setterlund, 1994). Due to the selective activation of an affect-related associative base, mood-congruent information may receive greater attention and be processed more extensively than affectively neutral or incongruent information (Bower, 1981). Several experiments have demonstrated that people spend longer reading mood-congruent material, linking it into a richer network of primed associations, and as a result, they are better able to remember such information (see Bower & Forgas, 2000).

These effects occur because “concepts, words, themes, and rules of inference that are associated with that emotion will become primed and highly available for use . . . [in] . . . top-down or expectation-driven processing . . . [acting] . . . as interpretive filters of reality” (Bower, 1983, p. 395). Thus, there is a tendency for people to process mood-congruent material more deeply, with greater associative elaboration, and thus learn it better. Consistent with this notion, depressed psychiatric patients tend to show better learning and memory for depressive words (Watkins, Mathews, Williamson, & Fuller, 1992), a bias that disappears once the depressive episode is over (Bradley & Mathews, 1983). However, mood-congruent learning is seldom seen in patients suffering from anxiety (Burke & Mathews, 1992; Watts & Dalgleish, 1991), perhaps because anxious people tend to use particularly vigilant, motivated processing strategies to defend against anxietyarousing information (Ciarrochi & Forgas, 1999; Mathews & MacLeod, 1994). Thus, as predicted by the AIM, different processing strategies appear to play a crucial role in mediating mood congruence in learning and attention.

Mood Congruence in Memory

Several experiments have shown that people are better able to consciously or explicitly recollect autobiographical memories that match their prevailing mood (Bower, 1981). Depressed patients display a similar pattern, preferentially remembering aversive childhood experiences, a memory bias that disappears once depression is brought under control (Lewinsohn & Rosenbaum, 1987). Consistent with the AIM, these mood-congruent memory effects also emerge when people try to recall complex social stimuli (Fiedler, 1991; Forgas, 1993).

Research using implicit tests of memory, which do not require conscious recollection of past experience, also provides evidence of mood congruence. For example, depressed people tend to complete more word stems (e.g., can) with negative than with positive words they have studied earlier (e.g., cancer vs. candy; Ruiz-Caballero & Gonzalez, 1994). Similar results have been obtained in other studies involving experimentally induced states of happiness or sadness (Tobias, Kihlstrom, & Schacter, 1992).

Mood Congruence in Associations and Interpretations

Cognitivetasksoftenrequireusto“gobeyondtheinformation given,” forcing people to rely on associations, inferences, and interpretations to construct a judgment or a decision, particularly when dealing with complex and ambiguous social information (Heider, 1958).Affect can prime the kind of associations used in the interpretation and evaluation of a stimulus (Clark & Waddell, 1983). The greater availability of moodconsistent associations can have a marked influence on the top-down, constructive processing of complex or ambiguous details (Bower & Forgas, 2000). For example, when asked to freely associate to the cue life, happy subjects generate more positive than negative associations (e.g., love and freedom vs. struggle and death), whereas sad subjects do the opposite (Bower, 1981). Mood-congruent associations also emerge when emotional subjects daydream or make up stories about fictional characters depicted in the Thematic Apperception Test (Bower, 1981).

Such mood-congruent effects can have a marked impact on many social judgments, including perceptions of human faces (Schiffenbauer, 1974), impressions of people (Forgas & Bower, 1987), and self-perceptions (Sedikides, 1995). However, several studies have shown that this associative effect is diminished as the targets to be judged become more clear-cut and thus require less constructive processing (e.g., Forgas, 1994, 1995). Such a diminution in the associative consequences of mood with increasing stimulus clarity again suggests that open, constructive processing is crucial for mood congruence to occur. Mood-primed associations can also play an important role in clinical states: Anxious people tend to interpret spoken homophones such as panepain or dye-die in the more anxious, negative direction (Eysenck, MacLeod, & Mathews, 1987), consistent with the greater activation these mood-congruent concepts receive. This same mechanism also leads to mood congruence in more complex and elaborate social judgments, such as judgments about the self and others, as the evidence reviewed in the following section suggests.

Mood Congruence in Self-Judgments

Affective states have a strong congruent influence on selfrelated judgments: Positive affect improves and negative affect impairs the valence of self-conceptions. In one study (Forgas, Bower, & Moylan, 1990), students who had fared very well or very poorly on a recent exam were asked to rate the extent to which their test performance was attributable to factors that were internal in origin and stable over time. Students made these attributions while they were in a positive or negative mood (induced by having them watch an uplifting or depressing video). Compared to their negative-mood counterparts, students in a positive mood were more likely to claim credit for success, making more internal and stable attributions for high test scores, but less willing to assume personal responsibility for failure, making more external and unstable attributions for low test scores.

An interesting and important twist to these results was revealed by Sedikides (1995), who asked subjects to evaluate a series of self-descriptions related to their behaviors or personality traits. Subjects undertook this task while they were in a happy, sad, or neutral mood (induced through guided imagery), and the time they took to make each evaluation was recorded.

Basing his predictions on the AIM, Sedikides predicted that highly consolidated core or “central” conceptions of the self should be processed quickly using the direct-access strategy and hence should show no mood-congruent bias; in contrast, less salient, “peripheral” self-conceptions should require more time-consuming substantive processing and accordingly be influenced by an affect-priming effect. The results supported these predictions, making Sedikides’s (1995) research the first to demonstrate differential mood-congruent effects for central versus peripheral conceptions of the self, a distinction that holds considerable promise for future research in the area of social cognition.

Affect also appears to have a greater congruent influence on self-related judgments made by subjects with low rather than high levels of self-esteem, presumably because the former have a less stable self-concept (Brown & Mankowski, 1993). In a similar vein, Smith and Petty (1995) observed stronger mood congruence in the self-related memories reported by low rather than high self-esteem individuals. As predicted by the AIM, these findings suggest that low selfesteem people need to engage in more open and elaborate processing when thinking about themselves, increasing the tendency for their current mood to influence the outcome.

Affect intensity may be another moderator of mood congruence: One recent study showed that mood congruence is greater among people who score high on measures assessing openness to feelings as a personality trait (Ciarrochi & Forgas, 2000). However, other studies suggest that mood congruence in self-judgments can be spontaneously reversed as a result of motivated-processing strategies. Sedikides (1994) observed that after mood induction, people initially generated self-statements in a mood-congruent manner. However, with the passage of time, negative self-judgments spontaneously reversed, suggesting the operation of an “automatic” process of mood management. Recent research by Forgas and Ciarrochi (in press) replicated these results and indicated further that the spontaneous reversal of negative self-judgments is particularly pronounced in people with high self-esteem.

In summary, moods have been shown to exert a strong congruent influence on self-related thoughts and judgments, but only when some degree of open and constructive processing is required and when there are no motivational forces to override mood congruence. Research to date also indicates that the infusion of affect into self-judgments is especially likely when these judgments (a) relate to peripheral, as opposed to central, aspects of the self; (b) require extensive, timeconsuming processing; and (c) reflect the self-conceptions of individuals with low rather than high self-esteem.

Mood Congruence in Person Perception

The AIM predicts that affect infusion and mood congruence should be greater when more extensive, constructive processing is required to deal with a task. Paradoxically, the more people need to think in order to compute a response, the greater the likelihood that affectively primed ideas will influence the outcome. Several experiments manipulated the complexity of the subjects’ task in order to create more or less demand for elaborate processing.

In one series of studies (Forgas, 1992), happy and sad subjects were asked to read and form impressions about fictional characters who were described as being rather typical or ordinary or as having an unusual or even odd combination of attributes (e.g., an avid surfer whose favorite music is Italian opera). The expectation was that when people have to form an impression about a complex, ambiguous, or atypical individual, they will need to engage in more constructive processing and rely more on their stored knowledge about the world in order to make sense of these stimuli. Affectively primed associations should thus have a greater chance to infuse the judgmental outcome.

Consistent with this reasoning, the data indicated that, irrespective of current mood, subjects took longer to read about odd as opposed to ordinary characters. Moreover, while the former targets were evaluated somewhat more positively by happy than by sad subjects, this difference was magnified (in a mood-congruent direction) in the impressions made of atypical targets. Subsequent research, comparing ordinary versus odd couples rather than individuals, yielded similar results (e.g., Forgas, 1993).

Do effects of a similar sort emerge in realistic interpersonal judgments? In several studies, the impact of mood on judgments and inferences about real-life interpersonal issues was investigated (Forgas, 1994). Partners in long-term, intimate relationships revealed clear evidence of mood congruence in their attributions for actual conflicts, especially complex and serious conflicts that demand careful thought. These experiments provide direct evidence for the process dependence of affect infusion into social judgments and inferences. Even judgments about highly familiar people are more prone to affect infusion when a more substantive processing strategy is used.

Recent research has also shown that individual characteristics, such as trait anxiety, can influence processing styles and thereby significantly moderate the influence of negative mood on intergroup judgments (Ciarrochi & Forgas, 1999). Low trait-anxious Whites in the United States reacted more negatively to a threatening Black out-group when experiencing negative affect. Surprisingly, high trait-anxious individuals showed the opposite pattern: They went out of their way to control their negative tendencies when feeling bad, and produced more positive judgments. Put another way, it appeared that low trait-anxious people processed information about the out-group automatically and allowed affect to influence their judgments, whereas high trait anxiety combined with aversive mood triggered a more controlled, motivated processing strategy designed to eliminate socially undesirable intergroup judgments.

Mood Congruence in Social Behaviors

Inthissectionwediscussresearchthatspeakstoarelatedquestion:Ifaffectcaninfluencethinkingandjudgments,canitalso influence actual social behaviors? Most interpersonal behaviorsrequiresomedegreeofsubstantive,generativeprocessing as people need to evaluate and plan their behaviors in inherently complex and uncertain social situations (Heider, 1958).

To the extent that affect influences thinking and judgments, there should also be a corresponding influence on subsequent social behaviors. Positive affect should prime positive information and produce more confident, friendly, and cooperative “approach” behaviors, whereas negative affect should prime negative memories and produce avoidant, defensive, or unfriendly attitudes and behaviors.

Mood Congruence in Responding to Requests

A recent field experiment by Forgas (1998) investigated affective influences on responses to an impromptu request. Folders marked “please open and consider this” were left on several empty desks in a large university library, each folder containing an assortment of materials (pictures as well as narratives) that were positive or negative in emotional tone. Students who (eventually) took a seat at these desks were surreptitiously observed to ensure that they did indeed open the folders and examine their contents carefully. Soon afterwards, the students were approached by another student (in fact, a confederate) and received an unexpected polite or impolite request for several sheets of paper needed to complete an essay. Their responses were noted, and a short time later they were asked to complete a brief questionnaire assessing their attitudes toward the request and the requester.

The results revealed a clear mood-congruent pattern in attitudes and in responses to the requester: Negative mood resulted in a more critical, negative attitude to the request and the requester, as well as less compliance, than did positive mood. These effects were greater when the request was impolite rather than polite, presumably because impolite, unconventional requests are likely to require more elaborate and substantive processing on the part of the recipient. This explanation was supported by evidence for enhanced longterm recall for these messages. On the other hand, more routine, polite, and conventional requests were processed less substantively, were less influenced by mood, and were also remembered less accurately later on. These results confirm that affect infusion can have a significant effect on determining attitudes and behavioral responses to people encountered in realistic everyday situations.

Mood Congruence in Self-Disclosure

Self-disclosure is one of the most important communicative tasks people undertake in everyday life, influencing the development and maintenance of intimate relationships. Self-disclosure is also critical to mental health and social adjustment. Do temporary mood states influence people’s self-disclosure strategies? Several lines of evidence suggest an affirmative answer: As positive mood primes more positive and optimistic inferences about interpersonal situations, self-disclosure intimacy may also be higher when people feel good.

In a series of recent studies (Forgas, 2001), subjects first watched a videotape that was intended to put them into either a happy or a sad mood. Next, subjects were asked to exchange e-mails with an individual who was in a nearby room, with a view to getting to know the correspondent and forming an overall impression of him or her. In reality, the correspondent was a computer that had been preprogrammed to generate messages that conveyed consistently high or low levels of self-disclosure.

As one might expect, the subjects’ overall impression of the purported correspondent was higher if they were in a happy than in a sad mood. More interestingly, the extent to which the subjects related their own interests, aspirations, and other personal matters to the correspondent was markedly affected by their current mood. Happy subjects disclosed more than did sad subjects, but only if the correspondent reciprocated with a high degree of disclosure. These results suggest that mood congruence is likely to occur in many unscripted and unpredictable social encounters, where people need to rely on constructive processing to guide their interpersonal strategies.

Synopsis

Evidence from many sources suggests that people tend to perceive themselves, and the world around them, in a manner that is congruent with their current mood. Over the past 25 years, explanations of mood congruence have gradually evolved from earlier psychodynamic and conditioning approaches to more recent cognitive accounts, such as the concept of affect priming, which Bower (1981; Bower & Cohen, 1982) first formalized in his well-known network theory of emotion.

With accumulating empirical evidence, however, it has also become clear that although mood congruence is a robust and reliable phenomenon, it is not universal. In fact, in many circumstances mood either has no effect or even has an incongruent effect on cognition. How are such divergent results to be understood?

The affect infusion model offers an answer. As discussed earlier, the model implies, and the literature indicates, that mood congruence is unlikely to occur whenever a cognitive task can be performed via a simple, well-rehearsed direct access strategy or a highly motivated strategy. In these conditions there is little need or opportunity for cognition to be influenced or infused by affect. Although the odds of demonstrating mood congruence are improved when subjects engage in heuristic processing of the kind identified with the AAI model, such processing is appropriate only under special circumstances (e.g., when the subjects’ cognitive resources are limited and there are no situational or motivational pressures for more detailed analysis).

According to the AIM, it is more common for mood congruence to occur when individuals engage in substantive, constructive processing to integrate the available information with preexisting and affectively primed knowledge structures. Consistent with this claim, the research reviewed here shows that mood-congruent effects are magnified when people engage in constructive processing to compute judgments about peripheral rather than central conceptions of the self, atypical rather than typical characters, and complex rather than simple personal conflicts. As we will see in the next section, the concept of affect infusion in general, and the idea of constructive processing in particular, may be keys to understanding not only mood congruence, but mood dependence as well.

Mood Dependence

Our purpose in this second half of the research paper is to pursue the problem of mood-dependent memory (MDM) from two points of view. Before delineating these perspectives, we should begin by describing what MDM means and why it is a problem.

Conceptually, mood dependence refers to the idea that what has been learned in a certain state of affect or mood is most expressible in that state. Empirically, MDM is often investigated within the context of a two-by-two design, where one factor is the mood—typically either happy or sad—in which a person encodes a collection of to-be-remembered or target events, and the other factor is the mood—again, happy versus sad—in which retention of the targets is tested. If these two factors are found to interact, such that more events are remembered when encoding and retrieval moods match than when they mismatch, then mood dependence is said to occur.

Why is MDM gingerly introduced here as “the problem”? The answer is implied by two quotations from Gordon Bower, foremost figure in the area. In an oft-cited review of the mood and memory literature, Bower (1981) remarked that mood dependence “is a genuine phenomenon whether the mood swings are created experimentally or by endogenous factors in a clinical population” (p. 134). Yet just eight years later, in an article written with John Mayer, Bower came to a very different conclusion, claiming that MDM is an “unreliable, chance event, possibly due to subtle experimental demand” (Bower & Mayer, 1989, p. 145).

What happened? How is it possible that in less than a decade, mood dependence could go from being a “genuine phenomenon” to an “unreliable, chance event”?

What happened was that, although several early studies secured strong evidence of MDM, several later ones showed no sign whatsoever of the phenomenon (see Blaney, 1986; Bower, 1987; Eich, 1989; Ucros, 1989). Moreover, attempts to replicate positive results rarely succeeded, even when undertaken by the same researcher using similar materials, tasks, and mood-modification techniques (see Bower & Mayer, 1989; Singer & Salovey, 1988). This accounts not only for Bower’s change of opinion, but also for Ellis and Hunt’s (1989) claim that “mood-state dependency in memory presents more puzzles than solutions” (p. 280) and for Kihlstrom’s (1989) comment that MDM “has proved to have the qualities of a will-o’-the-wisp” (p. 26).

Plainly, any effect as erratic as MDM appears to be must be considered a problem. Despite decades of dedicated research, it remains unclear whether mood dependence is a real, reliable phenomenon of memory. But is MDM a problem worth worrying about, and is it important enough to pursue? Many researchers maintain that it is, for the concept has significant implications for both cognitive and clinical psychology.

With respect to cognitive implications, Bower has allowed that when he began working on MDM, he was “occasionally chided by research friends for even bothering to demonstrate such an ‘obvious’triviality as that one’s emotional state could serve as a context for learning” (Bower & Mayer, 1989, p. 152). Although the criticism seems ironic today, it was incisive at the time, for many theories strongly suggested that memory should be mood dependent. These theories included the early drive-as-stimulus views held by Hull (1943) and Miller (1950), as well as such later ideas as Baddeley’s (1982) distinction between independent and interactive contexts, Bower’s (1981) network model of emotion, and Tulving’s (1983) encoding specificity principle. Thus, the frequent failure to demonstrate MDM reflects badly on many classic and contemporary theories of memory, and it blocks understanding of the basic issue of how context influences learning and remembering.

With respect to clinical implications, a key proposition in the prologue to Breuer and Freud’s (1895/1957) Studies on Hysteria states that “hysterics suffer mainly from reminiscences” (p. 7). Breuer and Freud believed, as did many of their contemporaries (most notably Janet, 1889), that the grand-mal seizures, sleepwalking episodes, and other bizarre symptoms shown by hysteric patients were the behavioral by-products of earlier traumatic experiences, experiences that were now shielded behind a dense amnesic barrier, rendering them impervious to deliberate, conscious recall. In later sections of the Studies, Freud argued that the hysteric’s amnesia was the result of repression: motivated forgetting meant to protect the ego, or the act of keeping something—in this case, traumatic recollections—out of awareness (see Erdelyi & Goldberg, 1979).

Breuer, however, saw the matter differently, and in terms that can be understood today as an extreme example of mood dependence. Breuer maintained that traumatic events, by virtue of their intense emotionality, are experienced in an altered or “hypnoid” state of consciousness that is intrinsically different from the individual’s normal state. On this view, amnesia occurs not because hysteric patients do not want to remember their traumatic experiences, but rather, because they cannot remember, owing to the discontinuity between their hypnoid and normal states of consciousness. Although Breuer did not deny the importance of repression, he was quick to cite ideas that concurred with his hypnoid hypothesis, including Delboeuf’s claim that “We can now explain how the hypnotist promotes cure [of hysteria]. He puts the subject back into the state in which his trouble first appeared and uses words to combat that trouble, as it now makes fresh emergence” (Breuer & Freud, 1895/1957, p. 7, fn. 1).

Since cases of full-blown hysteria are seldom seen today, it is easy to dismiss the work of Breuer, Janet, and their contemporaries as quaint and outmoded. Indeed, even in its own era, the concept of hypnoid states received short shrift: Breuer himself did little to promote the idea, and Freud was busy carving repression into “the foundation-stone on which the whole structure of psychoanalysis rests” (Freud, 1914/1957, p. 16). Nonetheless, vestiges of the hypnoid hypothesis can be seen in a number of contemporary clinical accounts. For instance, Weingartner and his colleagues have conjectured that mood dependence is a causal factor in the memory deficits displayed by psychiatric patients who cycle between states of mania and normal mood (Weingartner, 1978; Weingartner, Miller, & Murphy, 1977). In addition to bipolar illness, MDM has been implicated in such diverse disorders as alcoholic blackout, chronic depression, psychogenic amnesia, and multiple personality disorder (see Goodwin, 1974; Nissen, Ross, Willingham, MacKenzie, & Schacter, 1988; Reus, Weingartner, & Post, 1979).

Given that mood dependence is indeed a problem worth pursuing, how might some leverage on it be gained? Two approaches seem promising: one cognitive in orientation, the other, clinical. The former features laboratory studies involving experimentally induced moods in normal subjects, and aims to identify factors or variables that play pivotal roles in the occurrence of MDM. This approach is called cognitive because it focuses on factors—internally versus externally generated events, cued versus uncued tests of explicit retention, or real versus simulated moods—that are familiar to researchers in the areas of mainstream cognitive psychology, social cognition, or allied fields.

The alternative approach concentrates on clinical studies involving naturally occurring moods. Here the question of interest is whether it is possible to demonstrate MDM in people who experience marked shifts in mood state as a consequence of a psychopathological condition, such as bipolar illness. In the remainder of this research paper, we review recent research that has been done on both of these fronts.

Cognitive Perspectives on Mood Dependence

Although mood dependence is widely regarded as a nowyou-see-it, now-you-don’t effect, many researchers maintain that the problem of unreliability lies not with the phenomenon itself, but rather with the experimental methods meant to detect it (see Bower, 1992; Eich, 1995a; Kenealy, 1997). On this view, it should indeed be possible to obtain robust and reliable evidence of MDM, but only if certain conditions are met and certain factors are in effect.

What might these conditions and factors be? Several promising candidates are considered as follows.

Nature of the Encoding Task

Intuitively, it seems reasonable to suppose that how strongly memory is mood dependent will depend on how the to-beremembered or target events are encoded. To clarify, consider two hypothetical situations suggested by Eich, Macaulay, and Ryan (1994). In Scenario 1, two individuals—one happy, one sad—are shown, say, a rose and are asked to identify and describe what they see. Both individuals are apt to say much the same thing and to encode the rose event in much the same manner. After all, and with all due respect to Gertrude Stein, a rose is a rose is a rose, regardless of whether it is seen through a happy or sad eye. The implication, then, is that the perceivers will encode the rose event in a way that is largely unrelated to their mood. If true, then when retrieval of the event is later assessed via nominally noncued or spontaneous recall, it should make little difference whether or not the subjects are in the same mood they had experienced earlier. In short, memory for the rose event should not appear to be mood dependent under these circumstances.

Now imagine a different situation, Scenario 2. Instead of identifying and describing the rose, the subjects are asked to recall an episode, from any time in their personal past, that the object calls to mind. Instead of involving the relatively automatic or data-driven perception of an external stimulus, the task now requires the subjects to engage in internal mental processes such as reasoning, reflection, and cotemporal thought, “the sort of elaborative and associative processes that augment, bridge, or embellish ongoing perceptual experience but that are not necessarily part of the veridical representation of perceptual experience” (Johnson & Raye, 1981, p. 70). Furthermore, even though the stimulus object is itself affectively neutral, the autobiographical memories it triggers are apt to be strongly influenced by the subjects’ mood. Thus, for example, whereas the happy subject may recollect receiving a dozen roses from a secret admirer, the sad subject may remember the flowers that adorned his father’s coffin. In effect, the rose event becomes closely associated with or deeply collared by the subject’s mood, thereby making mood a potentially potent cue for retrieving the event. Thus, when later asked to spontaneously recall the gist of the episode they had recounted earlier, the subjects should be more likely to remember having related a vignette involving roses if they are in the same mood they had experienced earlier. In this situation, then, memory for the rose event should appear to be mood dependent.

These intuitions accord well with the results of actual research. Many of the earliest experiments on MDM used a simple list-learning paradigm—analogous to the situation sketched in Scenario 1—in which subjects memorized unrelated words while they were in a particular mood, typically either happiness or sadness, induced via hypnotic suggestions, guided imagery, mood-appropriate music, or some other means (see Martin, 1990). As Bower (1992) has observed, the assumption was that the words would become associated, by virtue of temporal contiguity, to the subjects’ current mood as well as to the list-context; hence, reinstatement of the same mood would be expected to enhance performance on a later test of word retention. Although a few list-learning studies succeeded in demonstrating MDM, several others failed to do so (see Blaney, 1986; Bower, 1987).

In contrast to list-learning experiments, studies involving autobiographical memory—including those modeled after Scenario 2—have revealed robust and reliable evidence of mood dependence (see Bower, 1992; Eich, 1995a; Fiedler, 1990). An example is Experiment 2 by Eich et al. (1994). During the encoding session of this study, undergraduates completed a task of autobiographical event generation while they were feeling either happy (H) or sad (S), moods that had been induced via a combination of music and thought. The task required the students to recollect or generate a specific episode or event, from any time in their personal past, that was called to mind by a common-noun probe, such as rose; every subject generated as many as 16 different events, each elicited by a different probe. Subjects described every event in detail and rated it along several dimensions, including its original emotional valence (i.e., whether the event seemed positive, neutral, or negative when it occurred).

During the retrieval session, held two days after encoding, subjects were asked to recall—in any order and without benefit of any observable reminders or cues—the gist of as many of their previously generated events as possible, preferably by recalling their precise corresponding probes (e.g., rose). Subjects undertook this test of autobiographical event recall either in the same mood in which they had generated the events or in the alternative affective state, thus creating two conditions in which encoding and retrieval moods matched (H/H and S/S) and two in which they mismatched (H/S and S/H).

Results of the encoding session showed that when event generation took place in a happy as opposed to a sad mood, subjects generated more positive events (means = 11.1 vs. 6.7), fewer negative events (3.3 vs. 6.8), and about the same small number of neutral events (1.2 vs. 2.0). This pattern replicates many earlier experiments (see Bower & Cohen, 1982; Clark & Teasdale, 1982; Snyder & White, 1982), and it provides evidence of mood-congruent memory.

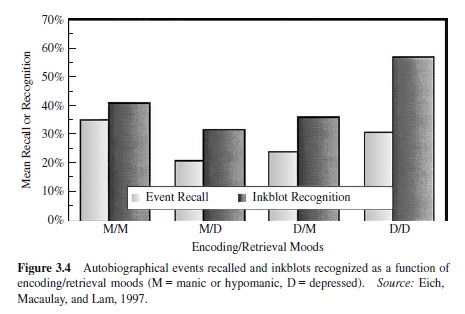

Results of the retrieval session provided evidence of mood-dependent memory. In comparison with their mismatchedmood counterparts, subjects whose encoding and retrieval moods matched freely recalled a greater percentage of positive events (means = 37% vs. 26%), neutral events (32% vs. 17%), and negative events (37% vs. 27%). Similar results were obtained in two other studies using moods instilled throughmusicandthought(Eichetal.,1994,Experiments1& 3), as well as in three separate studies in which the subjects’ affective states were altered by changing their physical surroundings (Eich, 1995b). Moreover, a significant advantage in recall of matched over mismatched moods was observed in recent research (described later) involving psychiatric patients who cycled rapidly and spontaneously between states of mania or hypomania and depression (Eich, Macaulay, & Lam, 1997). Thus, it seems that autobiographical event generation, when combined with event free recall, constitutes a useful tool for exploring mood-dependent effects under both laboratory and clinical conditions, and that these effects emerge in conjunction with either exogenous (experimentally induced) or endogenous (naturally occurring) shifts in affective state.

Recall that this section started with some simple intuitions about the conditions under which mood-dependent effects would, or would not, be expected to occur. Although the results reviewed thus far fit these intuitions, the former are by no means explained by the latter. Fortunately, however, there have been two recent theoretical developments that provide a clearer and more complete understanding of why MDM sometimes comes, sometimes goes.

One of these developments is the affect infusion model, which we have already considered at length in connection with mood congruence.As noted earlier, affect infusion refers to “the process whereby affectively loaded information exerts an influence on and becomes incorporated into the judgmental process, entering into the judge’s deliberations and eventually coloring the judgmental outcome” (Forgas, 1995, p. 39). For present purposes, the crucial feature of AIM is its claim that

Affect infusion is most likely to occur in the course of constructive processing that involves the substantial transformation rather than the mere reproduction of existing cognitive representations; such processing requires a relatively open information search strategy and a significant degree of generative elaboration of the available stimulus details. This definition seems broadly consistent with the weight of recent evidence suggesting that affect “will influence cognitive processes to the extent that the cognitive task involves the active generation of new information as opposed to the passive conservation of information given” (Fiedler, 1990, pp. 2–3). (Forgas, 1995, pp. 39–40)

Although the AIM is chiefly concerned with mood congruence, it is relevant to mood dependence as well. Compared to the rote memorization of unrelated words, the task of recollecting and recounting real-life events would seem to place a greater premium on active, substantive processing, and thereby promote a higher degree of affect infusion. Thus, the AIM agrees with the fact that list-learning experiments often fail to find mood dependence, whereas studies involving autobiographical memory usually succeed.

The second theoretical development relates to Bower’s (1981; Bower & Cohen, 1982) network model of emotions, which has been revised in light of recent MDM research (Bower, 1992; Bower & Forgas, 2000). A key aspect of the new model is the idea, derived from Thorndike (1932), that in order for subjects to associate a target event with their current mood, contiguity alone between the mood and the event may not be sufficient. Rather, it may be necessary for subjects to perceive the event as enabling or causing their mood, for only then will a change in mood cause that event to be forgotten.

To elaborate, consider first the conventional list-learning paradigm, alluded to earlier. According to Bower and Forgas (2000, p. 97), this paradigm is ill suited to demonstrating MDM, because it

arranges only contiguity, not causal belonging, between presentation of the to-be-learned material and emotional arousal. Typically, the mood is induced minutes before presentation of the learning material, and the mood serves only as a prevailing background; hence, the temporal relations are not synchronized to persuade subjects to attribute their emotional feelings to the material they are studying. Thus, contiguity without causal belonging produces only weak associations at best.

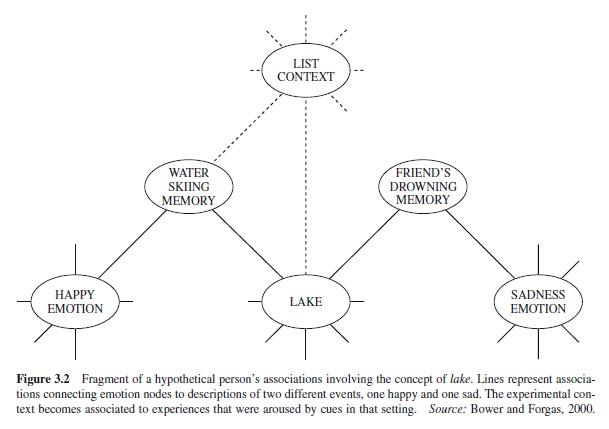

In contrast, the model allows for strong mood-dependent effects to emerge in studies of autobiographical memory, such as those reported by Eich et al. (1994). Referring to Figure 3.2, which shows a fragment of a hypothetical associative structure surrounding the concept lake, Bower and Forgas (2000, pp. 97–98) propose the following:

Suppose [that a] subject has been induced to feel happy and is asked to recall an incident from her life suggested by the target word lake. This concept has many associations including several autobiographic memories, a happy one describing a pleasantly thrilling water-skiing episode, and a sad one recounting an episode of a friend drowning in a lake. These event-memories are connected to the emotions the events caused. When feeling happy and presented with the list cue lake, the subject is likely (by summation of activation) to come up with the water-skiing memory. The subject will then also associate the list context to the water-skiing memory and to the word lake that evoked it. These newly formed list associations [depicted by dashed lines in Figure 3.2] are formed by virtue of the subject attributing causal belonging of the word-and-memory to the experimenter’s presentation of the item within the list.

These contextual associations are called upon later when the subject is asked to free recall the prompting words (or the memories prompted by them) when induced into the same mood or a different one. If the subject is happy at the time of recall testing, the water-skiing memory would be advantaged because it would receive the summation of activation from the happy-mood node and the list context, thus raising it above a recall level. On the other hand, if the subject’s mood at recall were shifted to sadness, that node has no connection to the water-skiing memory that was aroused during list input, so her recall of lake in this case would rely exclusively upon the association to lake of the overloaded, list-context node [in Figure 3.2].

Thus, the revised network model, like the AIM, makes a clear case for choosing autobiographical event generation over list learning as a means of demonstrating MDM.

Nature of the Retrieval Task

Moreover, both the AIM and the revised network model accommodate an important qualification, which is that mood dependence is more apt to occur when retention is tested in the absence than in the presence of specific, observable reminders or cues (see Bower, 1981; Eich, 1980). Thus, free recall seems to be a much more sensitive measure of MDM than is recognition memory, which is why the former was the test of choice in all three of the autobiographical memory studies reported by Eich et al. (1994).

According to the network model, “recognition memory for whether the word lake appeared in the list [of probes] simply requires retrieval of the lake-to-list association; that association is not heavily overloaded at the list node, so its retrieval is not aided by reinstatement of the [event generation] mood” (Bower & Forgas, 2000, p. 98). In contrast, the AIM holds that recognition memory entails direct-access thinking, Forgas’s (1995) term for cognitive processing that is simpler, more automatic, and less affectively infused than that required for free recall.

In terms of their overall explanatory power, however, the AIM may have an edge over the revised network model on two accounts. First, although many studies have sought, without success, to demonstrate mood-dependent recognition (see Bower & Cohen, 1982; Eich & Metcalfe, 1989; for exceptions, see Beck & McBee, 1995; Leight & Ellis, 1981), most have used simple, concrete, and easily codable stimuli (such as common words or pictures of ordinary objects) as the target items. However, this elusive effect was revealed in a recent study (Eich et al., 1997; described in more detail later) in which bipolar patients were tested for their ability to recognize abstract, inchoate, Rorschach-like inkblots, exactly the kind of complex and unusual stimuli that the AIM suggests should be highly infused with affect.

Second, although the network model deals directly with differences among various explicit measures of mood dependence (e.g., free recall vs. recognition memory), it is less clear what the model predicts vis-à-vis implicit measures. The AIM, however, implies that implicit tests may indeed be sensitive to MDM, provided that the tests call upon substantive, open-ended thinking or conceptually driven processes (see Roediger, 1990). To date, few studies of implicit mood dependence have been reported, but their results are largely in line with this reasoning (see Kihlstrom, Eich, Sandbrand, & Tobias, 2000; Ryan & Eich, 2000).

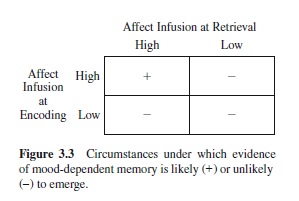

Before turning to other factors that figure prominently in mood dependence, one more point should be made. Throughout both this section and the previous one, we have suggested several ways in which the affect infusion model may be brought to bear on the basic problem of why MDM occurs sometimes but not others. Figure 3.3 tries to tie these various suggestions together into a single, overarching idea—specifically, that the higher the level of affect infusion achieved both at encoding and at retrieval, the better the odds of demonstrating mood dependence.

Although certainly simplistic, this idea accords well with what is now known about mood dependence, and, more important, it has testable implications. As a concrete example, suppose that happy and sad subjects read about and form impressions of fictional characters, some of whom appear quite ordinary and some of whom seem rather odd. As discussed earlier, the AIM predicts that atypical, unusual, or complex targets should selectively recruit longer and more substantive processing strategies and correspondingly greater affect infusion effects. Accordingly, odd characters should be evaluated more positively by happy than by sad subjects, whereas ordinary characters should be perceived similarly, a deduction that has been verified in several studies (Forgas, 1992, 1993). Now suppose that the subjects are later asked to freely recall as much as they can about the target individuals, and that testing takes place either in the same mood that had experienced earlier or in the alternative affect. The prediction is that, relative to their mismatched mood peers, subjects tested under matched mood conditions will recall more details about the odd people, but an equivalent amount about the ordinary individuals. More generally, it is conceivable that mood dependence, like mood congruence, is enhanced by the encoding and retrieval of atypical, unusual, or complex targets, for the reasons given by the AIM. Similarly, it may be that judgments about the self, in contrast to others, are more conducive to demonstrating MDM, as people tend to process self-relevant information in a more extensive and elaborate manner (see Forgas, 1995; Sedikides, 1995). Possibilities such as these are inviting issues for future research on mood dependence.

Strength, Stability, and Sincerity of Experimentally Induced Moods

To this point, our discussion of MDM has revolved around the idea that certain combinations of encoding tasks and retrieval tests may work better than others in terms of evincing robust and reliable mood-dependent effects. It stands to reason, however, that even if one were to able to identify and implement the ideal combination, the chances of demonstrating MDM would be slim in the absence of an effective manipulation of mood. So what makes a mood manipulation effective?

One consideration is mood strength. By definition, mood dependence demands a statistically significant loss of memory when target events are encoded in one mood and retrieved in another. As Ucros (1989) has remarked, it is doubtful whether anything less than a substantial shift in mood, between the occasions of event encoding and event retrieval, could produce such an impairment. Bower (1992) has argued a similar point, proposing that MDM reflects a failure of information acquired in one state to generalize to the other, and that generalization is more apt to fail the more dissimilar the two moods are.

No less important than mood strength is mood stability over time and across tasks. In terms of demonstrating MDM, it does no good to engender a mood that evaporates as soon as the subject is given something to do, like memorize a list of words or recall a previously studied story. It is likely that some studies failed to find mood dependence simply because they relied on moods that were potent initially but that paled rapidly (see Eich & Metcalfe, 1989).

Yet a third element of an effective mood is its authenticity or emotional realism. Using the autobiographical event generation and recall tasks described earlier, Eich and Macaulay (2000) found no sign whatsoever of MDM when undergraduates simulated feeling happy or sad, when in fact their mood had remained neutral throughout testing. Moreover, in several studies involving the intentional induction of specific moods, subjects have been asked to candidly assess (postexperimentally) how authentic or real these moods felt.Those who claim to have been most genuinely moved tend to show the strongest mood-dependent effects (see Eich, 1995a; Eich et al., 1994).

Thus it appears that the prospects of demonstrating MDM are improved by instilling affective states that have three important properties: strength, stability, and sincerity. In principle, such states could be induced in a number of different ways; for instance, subjects might (a) read and internalize a series of self-referential statements (e.g., I’m feeling on top of the world vs. Lately I’ve been really down), (b) obtain false feedback on an ostensibly unrelated task, (c) receive a posthypnotic suggestion to experience a specified mood, or, as noted earlier, (d) contemplate mood-appropriate thoughts while listening to mood-appropriate music (see Martin, 1990). In practice, however, it is possible that some methods are better suited than others for inducing strong, stable, and sincere moods. Just how real or remote this possibly is remains to be seen through close, comparative analysis of the strengths and shortcomings of different mood-induction techniques.

Synopsis

The preceding sections summarized recent efforts to uncover critical factors in the occurrence of mood-dependent memory. What conclusions can be drawn from this line of work?

The broadest and most basic conclusion is that the problem of unreliability that has long beset research on MDM may not be as serious or stubborn as is commonly supposed. More to the point, it now appears that robust and reliable evidence of mood dependence can be realized under conditions in which subjects (a) engage in open, constructive, affectinfusing processing as they encode the to-be-remembered or target targets; (b) rely on similarly high-infusion strategies as they endeavor to retrieve these targets; and (c) experience strong, stable, and sincere moods in the course of both event encoding and event retrieval.

Taken together, these observations make a start toward demystifying MDM, but only a start. To date, only a few factors have been examined for their role in mood dependence; the odds are that other factors of equal or greater significance exist, awaiting discovery. Also, it remains to be seen whether MDM occurs in conjunction with clinical conditions, such as bipolar illness, and whether the results revealed through research involving experimentally engendered moods can be generalized to endogenous or natural shifts in affective state. The next section reviews a recent study that relates to these and other clinical issues.

Clinical Perspectives on Mood Dependence

Earlier it was remarked that mood dependence has been implicated in a number of psychiatric disorders. Although the MDM literature is replete with clinical conjectures, it is lacking in hard clinical data. Worse, the few pertinent results that have been reported are difficult to interpret.