Sample Experimentation In Psychology Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

From the very beginning of their studies, psychology students in Western countries learn that the discipline specializes in quantitative research rather than ‘armchair philosophy.’ Methodological and statistical textbooks teach how to measure individual or group characteristics such as intelligence, neuroticism, or attitudes. Moreover, introductory and advanced textbooks spell out rules of experimentation for tracing the causes of the psychological characteristics that are measured or evaluating attempts at improving them. Standardized experimentation in particular constitutes the core of psychology’s scientific identity.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The typical psychological experiment compares one or more treated experimental groups to an untreated control group. As natural groups may vary in many more respects than only the hypothesized cause or treatment to be tested, experimenters must compose their own groups equal in all respects but the factor concerned. The ideal way to create comparable groups is to assign subjects to groups on the basis of chance and thus cancel out unwanted between-group differences. From the 1940s in America and from the 1960s in Europe, generations of psychologists have been taught that the exemplary experiment is an experiment in which randomly composed experimental and control groups are compared. Statistical inference testing is employed for establishing the significance of any differences in the results.

1. The Origins Of The Exemplary Design

Psychology textbooks typically discuss the experiment comparing randomly composed experimental and control groups (from now on ‘the random group experiment’) as being ‘the’ scientific experiment. They implicitly suggest or explicitly state that this form of experiment was borrowed directly from the natural sciences (more on the definition of an experiment in psychology textbooks can be found in Winston and Blais 1996). Yet, as has been demonstrated by researchers of science, in natural sciences such as physics and chemistry there are various ways of experimenting, and these are mostly learned during apprenticeship and via exemplars rather than through isolated methodology books and courses (Kuhn 1962). Moreover, comparing random groups is not a key experimental practice in such sciences (Hacking 1983, Galison 1997).

Historical research suggests that comparing randomly composed groups is firmly rooted in psychology’s own experimental traditions, traditions which have changed together with changing social relations. The discipline’s present-day definition of what constitutes an ideal experiment was brought about bit-by-bit when methodological practices from nineteenth-century ‘psychophysical’ experimenters trying to discover the given laws of human perception were adopted and adapted by early twentieth-century educational psychologists looking for technically useful data. These educational psychologists then passed the random group design on to other branches of psychology and social sciences (Danziger 1990, Winston and Blais 1996, Dehue 1997).

1.1 Experimentation In Nineteenth-Century Psychophysics

Psychological experimentation began as an endeavor of mid-nineteenth-century gentlemen-scholars to discover the given design of human nature. The word ‘experiment’ could refer to all kinds of research other than naturalistic observation. Experimentation involved manipulating human sensation and perception within artificial situations. An important founder of psychological experimentation was the German scholar Gustav Fechner, who during the years 1845 to 1849 lifted his arms with a weight in each hand over 67,000 times. After each lifting, Fechner meticulously recorded whether he had been able to distinguish the heavier weight from the lighter. In this way he established the ‘just noticeable difference’ or ‘threshold of perception’ as well as the mathematical relationship between the weights as measured and the weights as perceived.

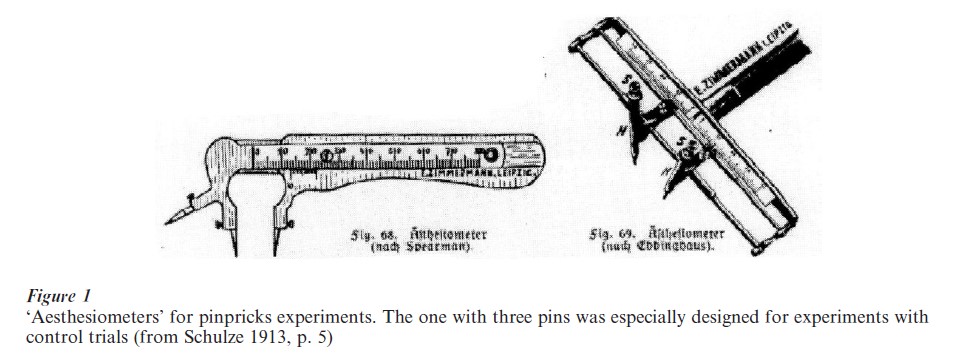

In Fechner’s time, the claim to measure anything as subjective as human sensation was novel and impressive. In the second half of the nineteenth century, innumerable ‘threshold experiments’ were conducted in biology, physiology, and particularly the newly established psychological laboratories at European and American universities. Countless extra weights were lifted, and Fechner’s methods of ‘psychophysical’ experimentation were employed for testing other senses as well. A popular variation was touching the skin with two pins at specific distances and trying to establish the minimum distance that can still be perceived (see Fig. 1). The different sensitivities of foreheads, chins, shoulders, arms, fingers, hips, bellies, legs, knees, and ankles were discussed. Neophytes would complain about sensitive and scaly skins and apologetically argue that some 6,000 pricks should be enough to draw a conclusion (Dehue 1997).

Like Fechner, the first psychophysical researchers acted as their own experimental subjects. Soon, however, the idea arose that the stimuli should be applied in random order, and that random control trials were needed. Researchers in Germany and subsequently the USA argued that the perception of distances might be biased by expectations on the next distance to come. Such expectations might be induced by awareness of the actual distances in previous trials or inadvertent regularities in previous series of trials. Moreover, it was argued, the sheer knowledge that there are always two pins might arouse the idea of perceiving a distance even if the actual distance is below the threshold of perception. For these reasons, it was decided that it takes two to experiment. Assistants were employed to apply the stimuli in random order as well as randomly carry out control trials in which the skin was touched at one point only without knowledge of the ‘observers’ (later on the individuals providing the stimuli would be called the ‘experimenters’ and the observers became the ‘subjects,’ see Danziger 1990 on the social meaning of such terminological changes). These were the first experiments employing randomization as a methodological means. In the 1880s, the American scholars Charles S. Peirce and Joseph Jastrow, moreover, introduced the first artificial randomizers. Distrusting the assistants’ ability to establish truly random orders, they used playing cards or dice (for a more extensive discussion and references, see Dehue 1997).

If the stimuli are indicated as ‘S,’ the responses as ‘R,’ and the randomly applied control trials (in which the actual double prick was withheld) as ‘noS,’ then the design of these experiments was something like S-R-noS-R-S-R-S-R-noS-R-S-R-noS-R-S-R-S-R (etc.). In later educational experimentation, the randomly inserted control trials (noS) were no longer conducted with the same subjects as the experimental trials (S) but with randomly composed control groups. This change implied the constitution of the random group design. In order to explain why that happened, some extra information should first be given on the methods of early psychophysics as well as social changes taking place outside the laboratories.

1.2 The ‘Transfer Of Training’ Phenomenon

Considerable concern about individual expectations and mistaken assessments became the hallmark of psychophysics. For the sake of replicability, utmost precision had to be exercised. The initiators of particular experiments extensively described the required laboratory setting, the instruments to be used, the handling of the instruments, as well as the required behaviors of assistants and observers both during the trials and in their spare time (Morawski 1988, Benschop and Draaisma 2000).

The researchers of just noticeable differences, however, were confronted with a rather obvious extra source of bias. After many trials, the skill of the experimental subjects improved, and this artificially lowered the threshold of perception. Switching to the other arm or leg did not solve the problem because the undesirable training seemed to transfer automatically to other parts of the body. The transfer phenomenon thwarted the experiments but also greatly intrigued the experimenters. Many of them became so fascinated by it that from a source of bias ‘transfer of training’ became a research topic of its own. At the end of the century, experiments were being conducted in American and European laboratories to establish the effects of training in all kinds of sensory, motor, and cognitive skills. Subjects were not only pinpricked. They were also asked to put needles through small holes with one hand and then checked for improvement with the other hand, or they were trained to tap their right big toe and tested for their ability with their left big toe (Bray 1928).

One has a mental picture of distinguished-looking men in suits sitting on wooden laboratory chairs and fiddling with needles or concentrating on their bare feet. But most importantly for the historical origination of the random group design, in these transfer of training studies the design of the threshold experiments had to be adapted. Once the stimuli had become trainings the original design of S-R-noS-R-S-R-S-RnoS-R-S-R-noS-R-S-R-S-R (etc.) was no longer feasible. Trainings cannot vary randomly as they cannot be haphazardly undone. Thus the standard design was limited to a particular ‘cutout’: (noS-) R-S-R. First a response (now an ability) was tested without preceding stimulus (now a training), next the training was given, and subsequently the ability was tested again. The transfer of training researchers worked with experimental groups whose abilities were compared before and after training.

1.3 Experimentation In Twentieth-Century Educational Psychology

While psychophysical experimenters were absorbed in their painstaking experiments, the world outside the laboratories was rapidly changing. In early-twentieth century Western countries, the common ideology of laissez-faire politics was widely replaced by that of planned social progress. Social amelioration gradually turned from a local charity matter into a concern of centralized government. The concomitant emergence of bureaucratic administration was to generate significant changes in the kind of knowledge about human functioning and human relations that was produced.

Whereas the authority of nineteenth-century local officials depended on their personal trustworthiness, the newly appointed administrators had to justify their decisions in terms of impersonal data and overt standards. Moreover, progress had to come about as economically as possible. The expanding class of bureaucratic officials turned to professional social researchers for knowledge that could serve the needs of administrative standardization and efficiency. With the shift from aristocratic to bureaucratic domination the former gentleman-scholar trying to discover the given laws of nature was increasingly replaced by the administrative researcher looking for technically useful data (Danziger 1990, Ross 1991, Porter 1995).

As far as psychology was concerned, the change was first brought about by psychophysical researchers taking an interest in educational administration. Around the turn of the twentieth century a debate blew up within American educational administrative circles on the utility of teaching subjects such as Latin and formal mathematics. School administrators wanted to abolish such subjects because of their apparent redundancy while proponents argued that ‘formal discipline’ strengthens general mental capacities. The issue reminded some American psychologists of the transfer of training phenomenon. Reasoning that formal discipline basically is a matter of transfer, they slightly adapted the former transfer experiments. They let subjects estimate weights or mark misspelled words, then trained them in estimating other weights or marking other misspelled words, and subsequently subjected them to the first tests again (NoS-R-S-R).

It may seem odd from a present-day perspective, but at the time a great deal of value was ascribed to the outcomes of such experiments. They seemed to provide an ideal basis for solid and impersonal decision-making. In the heat of the debate charges of experimental bias were soon made. In 1907, John E. Coover, a psychology student and former school principal, published an article on the issue (together with his teacher Frank Angell). The article argued that no valid causal conclusions can be drawn if the usual design of test-training-test (noS-R-S-R) was used (Coover and Angell 1907). With this strategy, the authors emphasized, it is impossible to tell whether the outcomes are caused by the training or by any other factor. The first test, for instance, might serve as a training too.

In experiments done for Coover’s 1905 master’s thesis, and described in the 1907 article, the solution was used of comparing ‘experimental reagents,’ who had been given a training, with ‘control reagents,’ who had not. With Coover’s design the usual sequence of (noS-) R-S-R was, so to speak, cut in two. The experimental group underwent the second part of S-R (training and test) and the control group only the first half of (noS-) R (a test without preceding training). In other words, the classical control trial in which the stimulus was withheld (noS), was now applied to special control subjects (more on the early introduction of the control group is given in Dehue 2000)

1.4 Creating Equal Groups

In the 1910s, experimental educational research began to thrive. Educational experimenters acquired contracts from school administrators and left their laboratories for experimentation in real schools. ‘Treatments’ to be assessed now included methods of memorizing, ways of teaching, educational measures such as punishing and praising, and all kinds of classroom circumstances. The idea of using a control group also spread. In the 1916 volume of the Journal of Educational Psychology, 14% of the articles reported the use of control groups (Danziger 1990, pp. 113–15). In the schools, however, life was much messier than in the former locations of psychophysical experimentation. It was much harder to protect experimental results against charges of arbitrariness. Methodological scrutiny became ever more important. It soon turned out that a price had to be paid for comparing the results of groups rather than comparing subjects to themselves. Contaminating factors between the pretest and the post-test were replaced by invalidating differences between the groups.

At first it became customary to handle the new problem by hypothesizing which factors could bias the results, then subjecting subjects to preliminary tests for these factors, and next forming groups with equal test results. For instance, for testing the efficacy of a new way of teaching, equal groups were created by first measuring the pupils’ intelligence and next composing equal groups as to mental capacity. With this ‘matching’ procedure, however, the choice of suspect factors depended very much on the researchers’ personal imagination. Possibly the sex of the children also makes a difference, or their social background, or any other factor. Moreover, matching was very time and money consuming. For the combined reasons of saving money and cancelling out subjectivity—the twin principles of administrative rationality—experimental psychologists again invoked the methodological use of chance.

In 1923, the American psychologist William McCall published a manual entitled How to Experiment in Education. In his introduction, McCall estimated that increased efficiency in education could save a full year of teaching per person, and worked out that psychological experimentation would save ‘$134,680,000,000,000 for the next 100 generations of Americans.’ He then he advanced a way of making his profession even more profitable to society, which was to compose the groups by chance. McCall did not take the task of randomization lightly. He rejected the procedure of writing numbers on pieces of paper, because papers with larger numbers contain more ink and are therefore likely to sink further to the bottom of a container. He nevertheless maintained that ‘any device which will make the selection truly random is satisfactory’ (McCall 1923, pp. 41–2).

Randomization, formerly used for creating random orders of stimuli, was now advanced as a cheap way of discarding unwanted differences between experimental groups. The random group design was first worked out in US educational psychology in the 1920s (on its later introduction in medicine, see Marks 1997).

2. A Guiding Rather Than Practicable Principle

While most psychology textbooks ascribe the random group design to natural science, some credit the British biometrician Ronald Fisher with it. Fisher developed the design in the 1930s for agricultural research. His methodological handbook, The Design of Experiments (1935), was widely received indeed. However, psychologists did not learn to use randomly composed groups from Fisher. From the 1920s onwards, educational experimenters had struggled with the complexity of data resulting from experiments simultaneously testing various experimental groups and comparing them to one control group. Fisher offered statistical techniques for analyzing such complex between-groups variance and assessing the significance of the results (on Fisher’s influence on psychology, see Gigerenzer and Murray 1987). His warnings that, for statistical reasons, these techniques could only be validly used if the groups were randomly composed added extra authority to psychologists already promoting the employment of random groups. In the 1940s, a range of handbooks on research design and statistics, mostly written by educational psychologists, passed on Fisher’s instructions to other branches of psychology. One of these methodological professionals was Quinn McNemar who would later observe that Fisher’s ways quickly ‘became epidemic just as though psychologists had never previously planned an experiment’ (McNemar 1960, p. 297).

At first, the combination of the random group design and significance testing seemed to provide an unquestionable experimental paradigm. Yet, in the context of experiments with humans, comparing random groups became an ideal mostly in the sense of a guiding principle rather than a viable strategy. Moral, legal, or practical reasons often prohibit people being given a treatment purely on the basis of chance. For example, the educational effects of prizes cannot be investigated by granting them at random, and differences in ethnic backgrounds among schools cannot be cancelled out by creating new classes on the basis of chance. Moreover, psychologists became involved with administrative research projects outside their traditional domain. From the 1930s, they were enlisted by other social scientists to measure the educational effects of radio talks and movies on issues such as voting, immigration, bootlegging, or war. In such contexts, it became all the more difficult to let the assignment of individuals to treatments depend purely on chance.

Renowned experiments by the US Army constitute a telling example of the unfeasibility of random assignment even with adult subjects living under command in a similar way to schoolchildren. During the Second World War, the Army’s ‘Morale Division’ was charged with improving the soldiers’ spirit. A film series entitled Why We Fight was made, and the Division’s experimental section, chiefly staffed with psychologists, was asked to investigate the films’ efficacy. The plan to evaluate the efficacy of these movies with the help of randomly composed groups did not work, as most soldiers became suspicious when some of them were summoned to see a movie while others were not. Random assignment thus appeared to elicit an unexpected new kind of bias. Although upon pre-testing the existing army units turned out to differ in many consequential respects, the units had to be used as experimental and control groups (Hovland 1949; for a history see Buck 1985).

After the war, the army experimenters were ensured of jobs at the best US universities (Herman 1995, p. 137). They widely propagated the standards of proper experimentation. Methodological treatises began to appear still advancing the random group design as the paragon form of experiment, but simultaneously indicating that unlike subjects in agricultural experimentation, people often cannot be assigned haphazardly to experimental conditions. Alternative designs and accompanying statistical techniques were developed.

Among the first methodologists to write in this vein was the young psychologist Donald Campbell, who also started his career in the army as an attitude and propaganda researcher. With the assistance of the statistician Julian Stanley, Campbell published a chapter entitled ‘Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research on Teaching.’ In 1966 the chapter was reprinted as a separate 83-page booklet with the briefer but more-embracing title of Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research (Campbell and Stanley 1966).

The book was the starting point of Campbell’s career as a renowned methodologist of social science. In the decades to come, innumerable publications and thick textbooks on ‘true’ and ‘quasi’ experimental designs by Campbell and many other authors in America and Europe were to follow. These works testify to the lasting high regard but limited applicability of random group experiments as well as their sociotechnical inspiration. As one of them summarized these three aspects in a striking comparison: ‘Most people after all do not drive around in Rolls Royces or Cadillacs, even if they represent some peak of automobile engineering perfection’ (Bulmer 1986, p. 170).

Bibliography:

- Benschop R, Draaisma D 2000 In pursuit of precision. The calibration of minds and machines in late nineteenth century psychology. Annals of Science 57(1): 1–25

- Bray C W 1928 Transfer of Learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology 11: 443–67

- Buck P 1985 Adjusting to military life: the social sciences go to war, 1941–1950. In: Smith M R (ed.) Military Enterprise and Technological Change: Perspectives on the American Experience. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Bulmer M 1986 Evaluation research and social experimentation. In: Bulmer M (ed.) Social Science and Social Policy. Allen and Unwin, London

- Campbell D T, Stanley J C 1966 Experimental and Quasi- experimental Designs for Research. R McNally, Chicago

- Coover J E, Angell F 1907 General practice effect of special exercise. American Journal of Psychology 18: 328–40

- Danziger K 1990 Constructing the Subject: Historical Origins of Psychological Research. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Dehue T 1997 Deception, efficiency and random groups. Psychology and the gradual origination of the random group design. Isis 88: 653–73

- Dehue T 2000 From deception-trials to control-reagents. The introduction of the control group about a century ago. American Psychologist 55(2): 264–268

- Fisher R A 1935 The Design of Experiments. Oliver & Boyde, Edinburgh, UK

- Galison P L 1997 Image and Logic: A Material Culture of Microphysics. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Gigerenzer G, Murray D J 1987 Cognition as Intuitive Statistics. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

- Hacking I 1983 Representing and Intervening. Introductory Topics in the Philosophy of Natural Science. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Herman E 1995 The Romance of American Psychology: Political Culture in the Age of Experts. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Hovland C I, Lumdsdaine A A, Sheffield F E 1949 Experiments on Mass Communication. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Kuhn T S 1962 The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago University Press, Chicago

- Marks H M 1997 The progress of experiment. Science and therapeutic reform in the United States, 1900–1990. Cambridge University Press, New York

- McCall W A 1923 How to Experiment in Education. Mcmillan, New York

- McNemar Q 1960 At random: sense and nonsense. American Psychologist 15: 295–300

- Morawski J G (ed.) 1988 The Rise of Experimentation in American Psychology. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT

- Porter T M 1995 Trust in Numbers: The Pursuit of Objectivity in Science and Public Life. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Ross D 1991 The Origins of American Social Science. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Schulze R 1913 Aus der Werkstatt der experimentellen Psychologie und Padagogik [From the workshop of experimental psychology and pedagogy]. Vogtlander Verlag, Leipzig, Germany

- Winston A S, Blais D J 1996 What counts as an experiment? A trans-disciplinary analysis of textbooks, 1930–1970. American Journal of Psychology 109: 599–616