Sample Green Revolution Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The term ‘green revolution’ was applied to land reform in Eastern Europe in the 1930s and recently to the attempts to persuade governments and business to adopt policies and practices that are not inimical to the environment. But the term is most commonly used in the social sciences to describe the changes that took place in farming in Asia after the introduction of semi dwarf wheat and rice varieties in the mid-1960s. If planted on irrigated land with the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides these crop varieties gave higher yields and greater profits than traditional ones. These innovations led to a substantial increase in the yield of wheat and rice, which was sustained until the 1990s when the rate of increase of yield and output declined; there may be difficulty in keeping cereal output ahead of population growth in the twenty-first century.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Early History

The period immediately following World War II in South Asia was characterized by rapid population growth, food shortages, and poverty. A great variety of wheat and rice varieties were in use, each adapted to their local micro-environment; little chemical fertilizer was used and no pesticides, and yields were low. In 1966 a semi-dwarf variety of rice known as IR8, bred at the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines, was distributed amongst farmers in parts of India, whilst a semi-dwarf wheat originally bred in Mexico was also introduced. Where these High Yielding Varieties (HYVs) were adopted, yields and output increased dramatically. This led W S Gaud to state in a lecture in the USA in 1968: ‘this and other developments in the field of agriculture contain the makings of a new revolution. It is not a violent Red Revolution like that of the Soviets … I call it the Green Revolution’(quoted in Dalrymple 1979). The importance of the Ford and Rockefeller foundations and of the US government in sponsoring the breeding programs in Mexico and the Philippines meant that much of the criticism of the new technology and its alleged consequences was ideological. The term ‘revolution’ was perhaps unfortunate. The breeding of higher yielding or disease-resistant varieties had been going on in Europe, North America, and parts of Asia since the rediscovery of Mendel’s work at the beginning of the twentieth century, whilst the use of chemical fertilizers and applications of pesticides had been practiced since the 1920s in Western Europe, although adopted at far greater rate after 1945. More relevant were the developments in Japan.

Much Japanese rice had long been irrigated, but the area irrigated was increased in the 1890s when the most successful existing rice varieties were selected and their seed distributed to farmers. Chemical fertilizers were also applied. By the 1930s, rice yields in Japan and its colonies Korea and Formosa were substantially above those elsewhere in Asia. Even in South Asia there had been advances in technology before 1966. Indian grain output increased by 62 percent before 1950 and 1964, and in Pakistan by 59 percent (Farmer 1981). Although rice yields in China in the 1950s were low compared with the rest of East Asia, semi-dwarf rices were bred there independently of the research in the Philippines and distributed to Chinese farmers before IR8 was released.

2. The Nature Of High Yielding Varieties (HYVs)

The principal characteristic of the HYVs were their high response to chemical fertilizers. They were also short with a stiff straw, and so, unlike the tall traditional varieties, did not lodge with higher yields. They were insensitive to photoperiodicity and matured in about 110 days rather than 180 days; it was thus possible to grow two or even three crops in a year. The yield potential of these varieties was greater in the temperate regions of Asia and in the dry season in the monsoon region than in the humid tropics, because of the longer hours of sunshine and hence the greater potential photosynthesis available to the plant. The highest yields are achieved in areas of well-managed irrigation and with adequate amounts of chemical fertilizers. At first the new varieties were highly susceptible to disease, and pesticides were necessary to obtain the high yield potential, but later varieties have been bred with a greater resistance to pests. Breeding of new varieties of rice and wheat has continued since the 1960s, increasingly in research stations in the countries where they are to be grown. High yielding varieties of maize have also proved successful and to a lesser extent new varieties of sorghum. Since the 1970s Chinese farmers have used hybrid rice seed. The new varieties introduced since the first HYVs are now often referred to as MVs (modern varieties).

3. The Diffusion Of The Modern Varieties

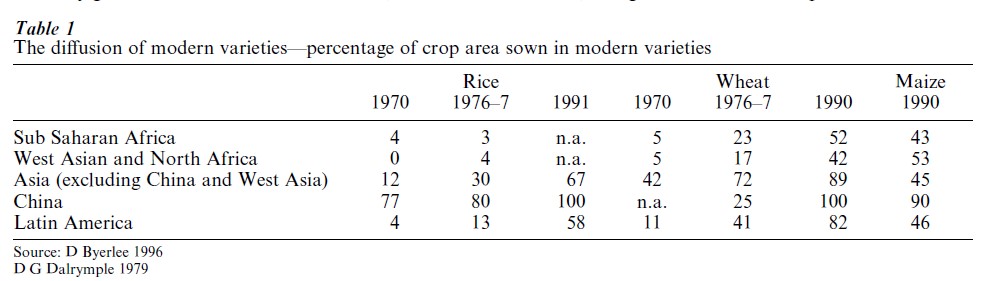

The inputs of the Green Revolution are divisible: seed, fertilizer, and pesticides can be bought in small amounts and so in theory could be obtained by farmers with only very small holdings. In practice however, the first adopters were generally occupiers of larger farms with better credit facilities and a greater awareness of the new technology. By the 1980s however, there was near universal adoption in irrigated areas with no differentiation of inputs by farm size or tenure. The principal incentive to adopt was the greater profit per hectare, in spite of the increased unit costs. At first the use of fertilizers and seeds were subsidized, and the improvement and extension of irrigation was undertaken by government. In the 1980s however, subsidies began to be withdrawn, and the further extension of irrigation had become very expensive. The introduction of modern varieties began at different times in different countries and different regions. Rice was introduced into India, for example, in 1965 but not in South Korea until 1972. The rate of adoption also differed; by 1976 four-fifths of all the rice in China was sown with modern varieties, but only 7 percent in Burma, 11 percent in Thailand, 14 percent in Bangladesh. National differences persisted in the 1990s (see Table 1).

Within countries there have also been major regional differences in the rate of adoption; thus in India in 1990, 95 percent of the rice in Punjab and Tamilnad was sown with modern varieties, but only one-third in Bihar and Kerala (Singh 1997). By the 1990s some of the major international differences in the rate of adoption had been reduced, but a greater proportion of Asia and Latin America’s wheat was sown with modern varieties than Africa or the Near East, whilst more of China’s was in new varieties than the rest of Asia (see Table 1). But of course there is a difference in the proportion of each continent sown in wheat, rice, maize, and other crops. Little wheat or rice is grown in tropical Africa, so the proportion of these crops in modern varieties is of little significance. This distribution explains why, in the mid-1980s, modern varieties were planted on less than one-third of the total cereal area in the developing countries: only 1 percent in Africa, 22 percent in Latin America and 36 percent in Asia (Tangley 1987).

4. The Consequences Of The Green Revolution

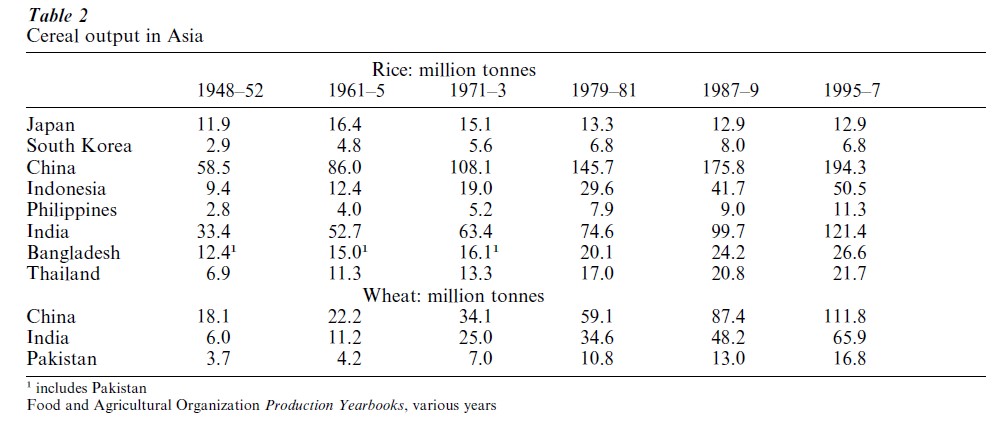

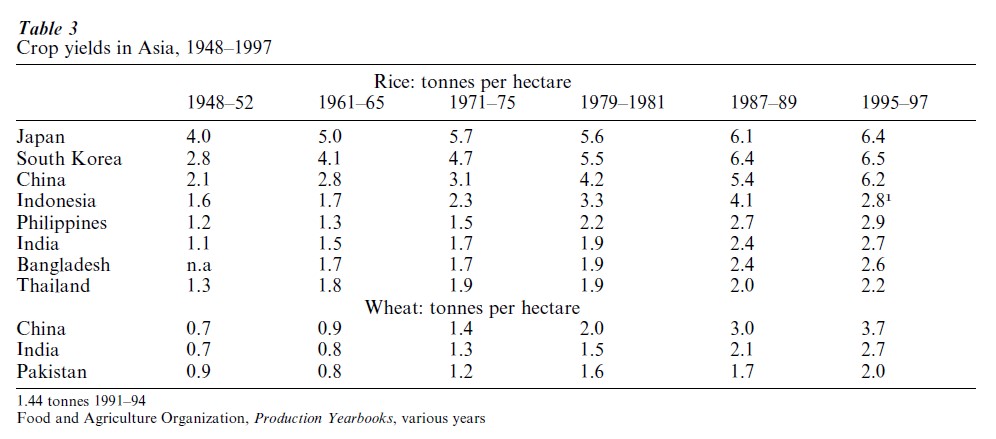

In the 1950s and 1960s it was feared that future population growth would outrun cereal output in Asia and increase malnutrition and hunger. This has not occurred. The rate of increase in output of both rice and wheat in Asia exceeded population growth rates between 1966 and 1995. Population increased 76 percent but rice output doubled; and the real price of rice has fallen steadily since the 1950s, halving between 1970 and 1990. Cereal consumption per capita has increased by 25 percent, imports have been greatly reduced, and grain reserves built-up. The increase has varied between countries (Table 2), and has been greater in wheat than rice output, but there have been dramatic increases in cereal harvests throughout the region. In the 1950s and 1960s increases in cereal output were largely due to an extension of the cultivated area; since the 1960s, overwhelmingly due to the increases in crop yields following the adoption of the new high-yielding varieties (Table 3).

The shorter growing season for HYVs has also allowed more double cropping in some parts of Asia. Yields have stagnated in the 1990s, however, particularly in Japan and Korea, which have the highest rice yields. The yield potential of the original HYVs has not been increased since the 1960s; the many new varieties bred since then have had greater disease resistance or better quality grain, but not greater yield potential. Additionally, in the high-producing irrigated rice areas, waterlogging, salinization, and disease have led in some places to a decline in yields. The fall in rice prices and the continued increase in import prices has squeezed cereal producers, and many have left farming or turned to more rewarding crops. In the last few years there have been renewed fears for the future of cereal output in Asia.

5. Criticisms Of The Green Revolution

Initially the Green Revolution was greeted with extravagant praise and high expectations. These were excessive, for it was unlikely that many farmers could reach the yields obtained on experimental farms, or that all farmers could profitably use the new techniques. A barrage of criticism followed to the present, although with changing targets. Controversy remains over the social and economic effects of the Green Revolution, nor is this surprising. There are three technical reasons why interpretations may differ. First, national and state statistics in India and other parts of Asia are not reliable and so different interpretations of changes are possible, particularly with reference to land tenure, farm size and labor. Second, it would be surprising if there were identical responses to new technology over such a vast area and population with greatly varying physical and socioeconomic environments. Third, research produces different results at different stages of the adoption cycle of agricultural innovations. It is unlikely that the consequences of technological change in the 1960s would be the same in the 1990s.

But there are other criticisms that are a result of the unequal distribution of farm sizes and land ownership. Early critics believed that the adoption of HYVs benefited the larger farmers most, often led small farmers to sell their land, increased landlessness, and forced down real wages. It was argued that while those with larger farms—and in most of Asia more than 20 acres is a large farm and most farmers have less than five acres—were able to rapidly adopt the new technology, and make considerable profits; smaller farmers were unable to do so and often sold their holdings to larger farmers, whilst many tenants were evicted to allow landowners to farm larger units. The number of landless households increased and so forced down real wages. In some areas the larger farmers adopted machinery to replace labor, and real incomes of the landless fell. Consequently income inequality increased.

These criticisms were made most fiercely in the early 1970s. At the time it was pointed out that many of these trends predated the ‘green revolution,’ or had alternative explanations. Machinery was being adopted before 1965, and rural population growth alone was sufficient to increase landlessness. Since then there have been more sample studies over longer periods (David and Otsuka 1994, Hazel and Ramasamy 1991). They have shown that small farmers have been able to adopt the new techniques, seed, and other inputs; that real wages have not fallen; and that the adoption of machinery has often been the result of farm laborers seeking higher paid jobs elsewhere. Other critics pointed out that the HYVs were only profitable in irrigated areas, and that improved varieties of only wheat and rice had been bred, yet in many parts of India farmers grew other cereal crops so that the benefits of the ‘green revolution’ occurred only in limited regions. This was true at that time, but subsequently modern varieties were bred that gave higher yields than traditional varieties in rainfed areas and with low amounts of fertilizer. Furthermore, high-yielding varieties of other crops have been bred: high-yielding maizes were bred in Kenya and Rhodesia before 1965, and now occupy half the African maize acreage, whilst in India high-yielding varieties of sorghum and millet have been bred. The early HYV rices had an inferior taste, and although subsequent varieties were of higher quality, richer consumers still prefer the taste of traditional varieties. Other critics were alarmed that the inputs for the new farms were imported, whilst some believed that that monoculture was replacing the diversity of cropping in traditional Asian farming, particularly the replacing of protein rich pulses with cereals.

By the 1990s new fears replaced these traditional concerns. Yields were—and still are—stagnating and even declining as a result of waterlogging and poor drainage in irrigated areas, whilst chemical pollution was becoming a problem. Falling cereal prices and rising costs are now threatening the future of cereal output, whilst Asia’s population may increase by 53 percent by 2030. It may be that a new technological advance will be necessary to maintain Asia’s freedom from famine that was the result of the ‘green revolution’ of the 1960s.

Bibliography:

- Burmeister L 1987 The South Korean green revolution: Induced or directed innovation. Economic Development and Cultural Change 35: 767–90

- Byerlee D 1996 Modern varieties, productivity and sustainability: Recent experience and emerging challenges. World Development 24: 697–718

- David C C, Otsuka K 1993 Modern Rice Technology and Income Distribution in Asia. Rienner, Boulder, CO

- Dalrymple D G 1979 The adoption of high-yielding grain varieties in developing nations. Agricultural History 53: 704–26

- Evenson R E, Herdt R W, Hossain M 1996 Recent Developments in the Asian Rice Economy: Challenges for Rice Research. CAB International, Wallingford, UK

- Farmer B H 1977 Green Revolution? Technology and Change in Rice-growing Areas of TamilNad. Westview, Boulder, CO

- Farmer B H 1981 The green revolution in South Asia. Geography 66: 202–7

- Griffin K 1974 The Political Economy of Agricultural Change: An Essay on the Green Revolution. Macmillan, London

- Hazell P B R, Ramasamy C 1991 The Green Revolution Reconsidered: The Impact of High-yielding Rice Varieties in South India. Johns Hopkins University Press, London

- Karim M B 1986 The Green Revolution: An International Bibliography:. Greenwood Press, New York

- Lipton M, Longhurst R 1989 New Seeds and Poor People. Unwin Hyman, London

- Pingali P L, Hossain M, Gerpacio R V 1997 Asian Rice Bowls. The Returning Crisis? CAB International, Wallingford, UK

- Shiva V 1989 The Violence of the Green Revolution. Natray Publishers, Dehra Dun, India

- Singh J 1997 Agricultural Development in South Asia. A Comparative Study in the Green Revolution Experiences. National Book Organisation, New Delhi, India

- Tangley L 1987 Beyond the green revolution. Bioscience 37: 176–80