Sample Ecological Inference Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of environmental research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

In nineteenth century Europe, suicide rates were higher in countries that were more heavily Protestant, the inference being that suicide was promoted by the social conditions of Protestantism (Durkheim 1897); also see Neeleman and Lewis (1999). According to Carroll (1975), death rates from breast cancer are higher in countries where fat is a larger component of the diet, the idea being that fat intake causes breast cancer. These are ‘ecological inferences,’ that is, inferences about individual behavior drawn from data about aggregates.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

To continue with Durkheim, the Protestant countries were different from the Catholic countries in many ways besides religion (the problem of ‘confounding’). Moreover, his data do not tie individual suicides to any particular religious faith. Confounding must be dealt with in any observational study. But the second problem—that exposure and response are measured only for aggregates rather than for individuals—is specific to ecological studies. If there is no confounding, the expected difference between effects for groups and effects for individuals is ‘aggregation bias’; in general, the difference is partly attributable to confounding and partly to aggregation bias.

The ecological fallacy consists of thinking that relationships observed for groups necessarily hold for individuals: if countries with more Protestants have higher suicide rates, then Protestants must be more likely to commit suicide; if countries with more fat in the diet have higher rates of breast cancer, then women who eat fatty foods must be more likely to get breast cancer. These inferences may be correct, but are only weakly supported by the aggregate data.

Ecological studies in epidemiology yielded important insights for Snow (1855), Finlay (1881), Goldberger (Terris 1964), and Dean (1938) among others. However, it is all too easy to draw incorrect conclusions from aggregate data. Greenland and Robins (1994) review the issues. For one example, recent studies of individual-level data cast serious doubt on the link between breast cancer and fat intake (Holmes et al. 1999). Another well-known example, on the sources of popular support for the Nazi party pre-war Germany, is discussed by Lohmoller et al. (1985)

1. Ecological Correlation

Robinson (1950) discusses ecological inference, stressing the difference between ecological correlations and individual correlations. One striking example is the relationship between nativity and literacy. For each of the 48 states in the US of 1930, Robinson computes two numbers: the percentage of the population who are foreign-born, and the percentage who are literate. (The base for each percentage is the number of residents of the state who are 10 or older; data are from the Census of 1930.) The correlation between the 48 pairs of numbers is 0.53. This is an ‘ecological’ correlation, because the unit of analysis is not an individual person but a group of people—the residents of a state. The ecological correlation suggests a positive association between foreign birth and literacy: the foreign-born are more likely to be literate (in American English) than the native-born. In reality, the association is negative: the correlation computed at the individual level is -0.11. The ecological correlation gives the wrong inference. The sign of the correlation is positive because the foreign-born tend to live in states where the native-born are relatively literate.

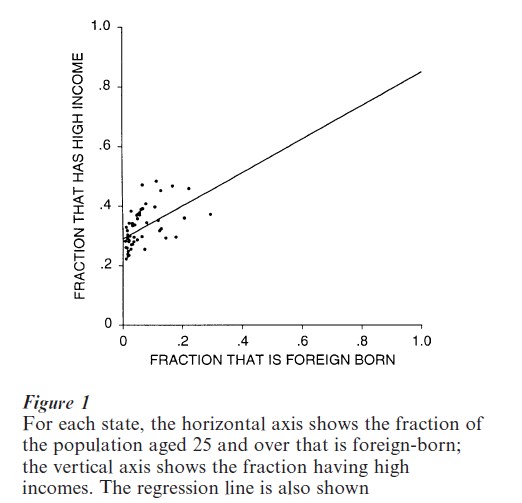

The example can be replicated using data from the March 1995 Current Population Survey, restricted to persons age 25 and over. Literacy is not reported, but incomes are. Say that a person has ‘high’ income if family income in 1994 was $50,000 or more. Figure 1 shows for each of the 50 states the fraction of persons who are foreign-born, and the fraction of persons who have high incomes. The regression line is shown too. The ecological correlation (across the 50 areas) is 0.52, suggesting that the foreign-born have higher incomes on the whole than the native-born. The truth is the opposite. About 35 percent of the native-born have high incomes, compared to 28 percent for the foreignborn. The correlation at the individual level is -0.05. In Fig. 1, there is no state where the fraction of foreign-born approaches 1. However, the same sort of reversal can occur even with a full spectrum of xvalues. The issue is the disaggregation, not the range of the data.

2. Ecological Regression

Under certain restrictive assumptions, individual behavior can be inferred from aggregate data using a technique called ‘ecological regression.’ The unit of analysis in the regression is a group of people, typically defined by geography (as in Fig. 1). The technique has been widely used in voting rights litigation in the US. For discussion from various perspectives, see Dogan and Rokkan (1969), Freedman et al. (1991), Grofman and Davidson (1992), Achen and Shively (1995), and Cho (1998).

It may, for instance, be desired to estimate the support for a particular candidate among Hispanics and non-Hispanics. For each precinct in an electoral contest, suppose we know the fraction x of voters who are Hispanic; we also know the fraction y of votes obtained by the candidate of interest. We would not know the fraction of Hispanic voters who voted for the candidate, due to the secrecy of the ballot.

A regression equation can be fitted to the data:

In Eqn. (1), the subscript i indexes precincts; xi is the fraction of voters in precinct i who are Hispanic; yi is the fraction of votes cast in that precinct for the candidate of interest. (More exactly, yi is the number of votes for that candidate, divided by the number of voters.) The precinct-level disturbance terms εi would typically be assumed to be independent and identically distributed with mean 0, although this is seldom made explicit.

The parameters a and b in Eqn. (1) can be estimated by ordinary least squares; call the estimates a and b, respectively. Then a would be interpreted as the fraction of non-Hispanic voters who supported the candidate in question: after all, a is the height of the regression line at x=0, corresponding to precincts with no Hispanic voters. Likewise, a+b (the height of the regression line at x=1) would be interpreted as the fraction of Hispanic voters who supported the candidate.

The data are available for groups defined by area of residence; the inference is to groups defined by ethnicity. The statistical logic connecting the inference to the data rests on the ‘constancy assumption,’ that voting preferences within ethnic groups do not systematically depend on the ethnic makeup of the area of the residence (Goodman 1953, 1959). In Fig. 1, the regression equation is y=0.29+0.56x, leading to the inference that 30 percent of the native-born have high incomes, compared to 29+56=85 percent of the foreign-born. In reality, as noted above, the percentages are 35 and 28 percent. The ecological inference is in error, because the constancy assumption fails: the incomes of the native-born increase systematically with fraction of foreign-born in the state. Immigration to the US tends to concentrate in richer states—California, Hawaii, and New York rather than Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia.

3. The Method Of Bounds

In 1995 in the state of Washington, 8 percent of the population was foreign born, while 34 percent had high incomes. These are known. Let p be the fraction of the foreign-born who had high incomes, and let q be the corresponding fraction for the native-born. Investigators making ecological inferences would typically not know the fractions p and q. The two unknowns satisfy an equation:

We have one equation with two unknowns: that is the whole problem of ecological inference. However, Eqn. (2) does contain some information, because q=(0.34-0.08p)/(1-0.08). Since p is bounded between 0 and 1, it follows that q is bounded below by (0.34-0.08)/(1-0.08)=0.26. Similarly, the upper bound is 0.34/0.92=0.37. This is ‘the method of bounds’ (Duncan and Davis 1953). Such bounds can be computed for each study area, and then aggregated. However, in typical applications, the bounds are too broad to be informative (also see Goodman 1959).

4. Ecological Regression With Random Coefficients

Models with random coefficients have been used to make ecological inferences. By way of illustration, we consider a model for nativity and income. Index the study areas by i. As before, let xi be the fraction of the population in area i that is foreign born, and yi the fraction with high incomes. These fractions are known, as is the total population ni of area i. Let pi be the fraction of the foreign-born with high incomes, and let qi be the corresponding fraction for the native-born, so

![]()

The problem is to make inferences about pi and qi. To solve such problems, King (1997) assumes the pairs (pi, qi) to be independent and identically distributed across the study areas. This is his version of the constancy assumption: the statistical behavior of a demographic group is not allowed to depend on area of residence. The parent distribution is taken to be bivariate normal, conditioned to lie in the unit square so that pi and qi are both between 0 and 1. The five parameters of this parent normal distribution can be estimated from the data by maximum likelihood, and estimates (pi, qi) can be derived from Eqn. (3). Rates for each demographic group can then be estimated by addition over areas, as ∑inipi /∑inixi and ∑iniqi /∑ini(1-xi), respectively. More complex models have also been developed.

To show the force of the constancy assumption, we can use the ‘neighborhood model’ which assumes that behavior is determined by geography not demography. Then pi = qi = yi for each study area i. (In our example of nativity and income, if 33 percent of the residents of a particular study area have high incomes, this percentage applies equally to the foreign-born and the native-born in that area.) The neighborhood model turns the constancy assumption on its head. In a variety of test applications where all the data are available, the neighborhood model gives more accurate estimates for demographic groups than ecological regression or random-coefficients models. In some contexts, of course, the neighborhood model proves deficient (Achen and Shively 1995). If the data are incomplete so estimation is needed, it will be unclear which model if any is giving the right answers. The track record to date favors the neighborhood model (Freedman et al. 1991, 1998). For another perspective see Schuessler (1999).

5. Summary And Conclusions

Aggregate data are often easier to obtain than data on individuals, and may offer valuable clues about individual behavior. Ecological inferences will therefore continue to be made. The problems of confounding and aggregation bias, however, are unlikely to be resolved in the proximate future.

Bibliography:

- Achen C H, Shively W P 1995 Cross-Level Inference. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Carroll K 1975 Experimental evidence of dietary factors and hormone-dependent cancers. Cancer Research 35: 3374–83

- Cho W K T 1998 Iff the assumption fits: A comment on the King ecological inference solution. Political Analysis 7: 143–63

- Dean H T 1938 Endemic fluorosis and its relation to dental caries. Public Health Reports 53: 1443–52

- Dogan M, Rokkan S (eds.) 1969 Quantitative Ecological Analysis in the Social Sciences. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Duncan O D, Davis B 1953 An alternative to ecological correlation. American Sociological Review 18: 665–6

- Durkheim E 1897 Le suicide. F. Alcan, Paris [English translation by J A Spalding, 1951, Free Press, Collier-MacMillan, Toronto, Canada]

- Finlay C J 1881 The mosquito hypothetically considered as the agent of transmission of yellow fever. Anales de la Academia de Ciencias Medicas, Fısicas y Naturales de Habana XVIII [English translation by Finlay, reprinted in Buck C, Llopis A, Najera E, Terris M 1989 The Challenge of Epidemiology: Issues and Selected Readings, Scientific Publication No. 505, World Health Organization, Geneva]

- Freedman D A, Klein S P, Ostland M, Roberts M R 1998 Review of A Solution to the Ecological Inference Problem. Journal of the American Statistical Association 93: 1518–22; with discussion, 1999, 94: 352–7

- Freedman D A, Klein S P, Sacks J, Smyth C A, Everett C G 1991 Ecological regression and voting rights. Evaluation Review 15: 659–817 (with discussion)

- Goodman L 1953 Ecological regression and the behavior of individuals. American Sociological Review 18: 663–4

- Goodman L 1959 Some alternatives to ecological correlation. American Journal of Sociology 64: 610–25

- Greenland S, Robins J 1994 Invited commentary: ecologic studies—biases, misconceptions, and counterexamples. American Journal of Epidemiology 139: 747–60

- Grofman B, Davidson C 1992 Controversies in Minority Voting: The Voting Rights Act in Perspective. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC

- Holmes M D, Hunter D J, Colditz G A, Stampfer M J, Hankinson S E, Speizer F E, Rosner B, Willett W C 1999 Association of dietary intake of fat and fatty acids with risk of breast cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association 281: 914–20

- King G 1997 A Solution to the Ecological Inference Problem. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey

- Lohmoller J B, Faller J, Link A, de Rifke J 1985 Unemployment and the rise of national socialism: contradicting results from different regional aggregations. In: Nijkamp P (ed.) Measuring the Unmeasurable. Martinus Nijhoof, Den Haag, pp. 357–70

- Neeleman J, Lewis G 1999 Suicide, religion and socioeconomic conditions. An ecological study in 26 countries, 1990. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 53: 204–10

- Robinson W S 1950 Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. American Sociological Review 15: 351–7

- Schuessler A A 1999 Ecological inference. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 96: 10578–81

- Snow J 1855 On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. Churchill, London. Reprinted by Hafner, New York, 1965

- Terris M 1964 Goldberger on Pellagra. Louisiana State University Press, Louisiana