Sample Environmentalism, Preservation, And Conservation Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, chech our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Environmentalism represents one of the most influential and enduring social movements of our time. Bursting onto the American scene in the late 1960s, the modern environmental movement has not only taken root in the USA but has spread across the globe. The environmental movement is widely considered to be one of the most successful social movements of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, especially in terms of gaining widespread societal acceptance of its goals (Dunlap 2000), and it is likely that it will continue to play an important role in regional, national, and global politics. This research paper traces the growth and diversification of modern environmentalism in the USA, briefly reviews the growth of environmentalism worldwide, and then examines the major stages of contemporary environmental activism—conservationism, environmentalism, and ecologism.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. The Emergence And Growth Of The US Environmental Movement

The organizational and ideological roots of contemporary environmentalism are commonly traced to the progressive conservation movement that emerged in the late nineteenth century in reaction to reckless exploitation of the United States’ natural resources. The progressive conservation movement is typically divided into two broad camps: utilitarian conservationists and romantic preservationists. While conservationists were interested primarily in the wise use and management of natural resources, preservationists were interested primarily in protecting natural areas from the encroachment of industrialization (Hays 1959, Nash 1982). Although the conservation movement faded from attention with World War I, it left a legacy of organizations (e.g., the Sierra Club and National Audubon Society) and government agencies (e.g., the National Park Service and the Forest Service). Additionally, the movement’s concerns were continued throughout the early to mid-twentieth century by projects such as the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Civilian Conservation Corps, and by environmental luminaries such as Bob Marshall and Aldo Leopold.

More recent explorations of the historical origins of environmentalism have begun to highlight additional, yet often neglected, precursors to the modern environmental movement (Taylor 1998). From the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s, middle and working-class whites developed an environmental agenda that focused on the creation of urban parks and the protection of public and industrial worker health and safety. This urban agenda, was, however, not strongly identifiable as a cohesive social movement. Unlike the conservation movement, it lacked a strong infrastructure and membership base, had few ties to powerful business and government interests, and lacked the strong symbolism and charismatic leaders that were the hallmarks of the conservation movement. Similarly, despite the existence of activism by and for people of color during this time, such activities have been eclipsed, not only by traditional historical accounts of environmentalism, but also by the public’s greater acknowledgement of conservationists and preservationists, both currently and historically.

The shift from its historical precursors to the modern environmental movement is typically marked by two events: the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 and the April 22, 1970 Earth Day celebration that drew millions of participants. The modern environmental movement emerged during an era of widespread political activism and reform, and quickly achieved high levels of support from the public, activists, and even elites—all of whom found environmental issues to be relatively appealing and consensual compared to the civil rights and anti-Vietnam protests.

The growth of scientific evidence on environmental degradation, eloquently documented in Silent Spring, coupled with media-enhanced disasters like the Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969, generated widespread concern. Post-World War II affluence enabled larger numbers of people to spend leisure time in the outdoors, heightening their commitment to preserving areas of natural beauty. Affluence, combined with increased urbanization and education, also stimulated changes in social values, lessening concern with materialism and generating interest in the quality of life, including environmental quality (Hays 1987).

At the same time, traditional conservation preservation organizations, such as the Sierra Club and the Wilderness Society, were aggressively battling threats to natural areas, and broadening their agendas to incorporate a variety of issues, including those espoused by the earlier generation of urban industrial activists (e.g., pollution and public health). Legal changes enabled organizations to fight battles on several fronts, from congressional offices to courtrooms, where legal standing was becoming easier to achieve. Furthermore, new organizations, such as the Environmental Defense Fund and the Natural Resources Defense Council, began to emerge, typically aided by foundation funding (Mitchell et al. 1992).

While the environmental movement is composed of numerous local and regional organizations, it is the large environmental organizations, such as those previously mentioned, that form the most visible face of contemporary environmentalism in the USA. Large environmental organizations have combined memberships numbering in the millions; they solicit and control multimillion-dollar budgets; and they employ large professional staffs of lobbyists, lawyers, and scientists. A core group of these organizations form what is known as the national ‘environmental lobby,’ a relatively influential, bureaucratic, and professionalized group of organizations headquartered in Washington, DC (Brulle 2000).

Despite predictions of movement demise and evidence of a decline in public support after the initial Earth Day, the movement remained strong throughout the 1970s, maintaining relatively high public support and continuing to gain in organizational membership. Ironically, the Reagan administration generated renewed support for environmentalism in the 1980s, as its anti-environmental agenda stimulated increased public support for environmental organizations (Dunlap 1995). The twentieth anniversary of Earth Day in 1990 witnessed the extensive involvement of Hollywood, politicians, and corporations. Although much of this reflected superficial commitment, the event was successful in stimulating major membership growth spurts in many environmental organizations (Mitchell et al. 1992). While growth in these organizations subsided somewhat in the 1990s, the thirtieth anniversary of Earth Day in 2000 yet again revealed the staying power of environmentalism. Environmental issues remain important to the public, the environment has become a significant factor in many political campaigns, and recycling programs and ‘ecologically correct’ products have become increasingly popular.

The environmental movement, like any social movement, is far from monolithic. Indeed, much of the success garnered by the ‘mainstream’ organizations (i.e., the environmental lobby) has engendered criticism that such organizations have become ossified, overly bureaucratic, and co-opted by the political and business interests of the status quo. Such criticism has fueled the development of a ‘radical fringe,’ a group of organizations and activists that advocate direct action (e.g., spiking trees, destroying bulldozers) and espouse ‘deep ecology,’ a philosophy grounded in self-identification with nature (Devall 1992). With the larger organizations ostensibly focusing more on their ‘bottom line’ (memberships and budgets) and safely maintaining their ties to powerful interests, radical groups argue that the mainstream environmental movement has become too willing to compromise in its efforts to protect the environment.

While radical groups argue that the mainstream movement has lost sight of nature, other environmentalists believe that the mainstream has lost sight of people. Grassroots groups fighting locally unwanted land uses (LULUs), such as toxic waste dumps or hazardous waste incinerators, have argued that the large organizations ignore their concerns in favor of more fashionable national and global issues (e.g., rainforest destruction or loss of biodiversity). Environmental justice activists have argued that the mainstream organizations have ignored issues of social justice (Bullard 1993). Mainstream organizations are not only dominated by middle and upper-class whites, but such organizations, it is argued, have ignored environmental issues faced by members of the working class and people of color. Because these grassroots and environmental justice groups focus heavily on public health issues that have a great impact on families and communities, women have played a more significant leadership role in them than has been true of the mainstream environmental movement.

As can be expected with any successful social movement, the environmental movement has generated opposition. Opposition to environmentalism comes from an incredibly diverse set of groups and activists, including well-organized industry groups, conservative think tanks, grassroots groups, and militant anti-environmentalists (Switzer 1997). Although industry groups have existed since the movement’s beginnings, it is the grassroots groups that have recently become more numerous as well as more organized. Whereas grassroots opposition was typically confined to the rural west (the Sagebrush Rebellion being the key antecedent in the 1970s and early 1980s), it has increasingly become a nationwide phenomenon. While some grassroots anti-environmental activism is funded by industry, much of it nonetheless stems from genuine local concern over the loss of control over management and use of land and other natural resources. The constituents of these grassroots groups include farmers, ranchers, miners, motorized recreationists, militia supporters, landowners—virtually anyone who feels negatively affected by governmental attempts to protect natural resources. Despite the growing activism of opposition groups, however, it remains to be seen whether they can succeed at significantly thwarting the publicly accepted environmental agenda in the USA.

2. Environmentalism Around The Globe

Environmentalism has clearly become a significant force in the USA. However, the USA is not unique in this regard, nor has environmentalism been confined to the ‘richer’ countries of the world. Not only is public support for environmental protection found around the globe (Dunlap and Mertig 1995), but activism on behalf of environmental protection has emerged in many nations, both industrialized and nonindustrialized.

Like the USA, other industrial nations have relatively well-organized and successful national-level environmental movements. The countries of Western Europe, in particular, have not only developed their own professionalized and institutionalized environmental organizations (with a corresponding growth in radical groups critical of the large organizations), but many have also established relatively successful Green parties that attempt to advance social as well as ecological concerns (Dalton 1994, Rootes 1997). The European Union’s emphasis on environmental protection is probably one sign that the environmental movement(s) within Europe have been quite successful in promoting their concerns.

In many countries, activism on behalf of environmental issues has a long history, even though it has typically not been labeled as environmentalism until relatively recently. This is perhaps most true of the poorer countries of the world, where colonization and imperialism have historically threatened not only the natural resource base but the very survival and livelihood of local peoples. For many people in poorer nations, such historical threats have not disappeared. Thus, it is no surprise to see activists in countries as varied as Malaysia, India, Thailand, Brazil, Nigeria, and Kenya fighting against international corporations to protect their forests and rivers, to promote sustainable development, and to safeguard biodiversity from the onslaught of transnational seed companies and other forces of globalization. Paralleling the movement for environmental justice in the USA, these activists are motivated by more than a concern for environmental protection; central among their concerns are those of social justice, the protection of livelihood, and the survival and well-being of family and community (Guha and Martinez-Alier 1997). This ‘environmentalism of the poor’ also counts women among its strongest leaders, for they are the ones who are most likely to see the devastating impact that resource shortages and environmental degradation can have on families.

Around the world, as in the USA, environmental activists and groups have also faced increasingly organized and sometimes violent opposition. From the bombing of a Greenpeace ship in New Zealand and the use of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPP) against anti-road activists in Britain, to the detention of anti-dam activists in Malaysia and the violent—occasionally murderous— attacks upon activists in Mexico, Costa Rica, Nigeria, and Brazil, there have been numerous instances of a growing global ‘backlash’ against environmentalism (Rowell 1996). While these events are certainly sobering for those involved in the environmental movement, most observers recognize that backlash reflects fear of a social movement’s success. As environmentalism gains strength around the world, it will undoubtedly generate growing opposition.

3. The Trajectory Of Environmental Activism In The USA

Despite the historical presence of other forms of environmental activism, especially those focused on early urban and industrial concerns, the progressive conservation movement is widely recognized as being the principal ancestor of modern environmentalism. Although modern environmentalism continues to encompass the concerns and tactics of the progressive conservation movement, it goes beyond them in substantial ways. Because the environmental movement is so qualitatively different from the progressive conservation movement, including both its preservationist and utilitarian branches, some scholars treat them as two separate movements, others as distinct stages of one broad movement. The predominant characteristics of what we identify as the three main stages of environmentalism in the USA—‘conservationism,’ ‘environmentalism,’ and the recently emerged ‘ecologism’—are juxtaposed below. In this discussion, the three stages are treated as parts of one broad and continuously evolving movement aimed at protecting environmental quality.

Rather than divorcing itself from its predecessors, each stage in this broad trajectory incorporates the concerns and tactics it inherited from earlier stages into its own, expanded agenda. For instance, ecologism does not ignore issues of resource management, the hallmark of conservationism, nor does it reject tactics such as political lobbying. In fact, the evolution of the movement has been marked by a gradual broadening of issues and growth in the diversity of groups dealing with such issues (Brulle 2000). While diversity exists in most mature social movements, and has been present in conservationism environmentalism since the early split between Gifford Pinchot’s utilitarian conservationists and John Muir’s preservationists, the modern movement encompasses an extraordinary diversity of organizations, goals, ideologies, and tactics. The scheme used here attempts to display the predominant characteristics of each stage, but it should be emphasized that substantial diversity exists at each stage, especially the third.

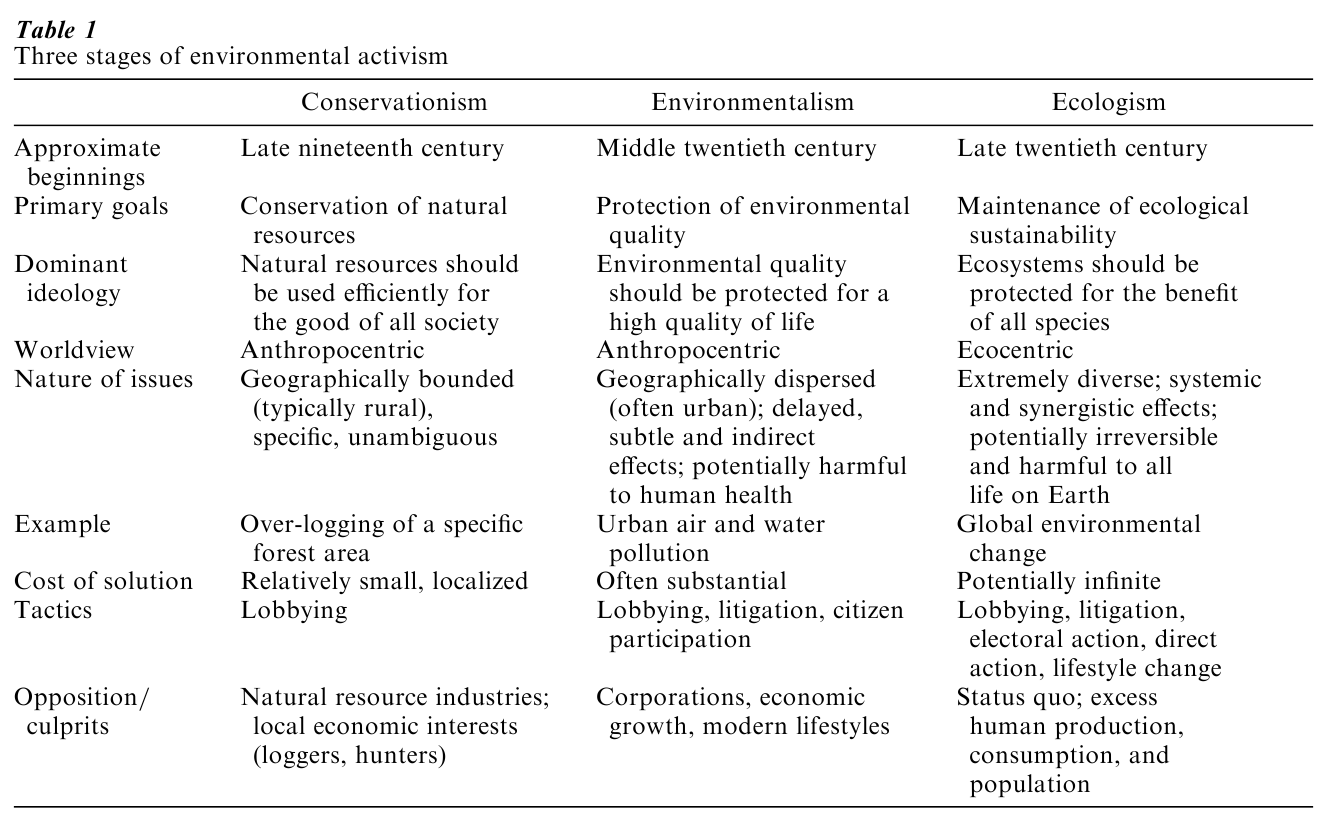

In Table 1, major characteristics of each stage of environmental activism are noted, starting with the approximate beginnings of each one. Conservationism dates to the late nineteenth century, when the progressive conservation movement emerged; environmentalism includes the bulk of the modern environmental movement that arose in the 1960s; and ecologism, it is argued, emerged in the last two decades of the twentieth century—partly in response to perceived weaknesses within mainstream environmentalism.

Social movement scholars distinguish movements (here, stages of one long-term movement) by their interrelated set of goals, ideologies, and world views. Movement goals are the primary focus of action for activists; ideology is a broad statement of what the movement considers to be an ‘ideal’ state of affairs; and world view is the lens through which activists perceive the world, in this case the natural world that they are attempting to protect. Of special relevance is the distinction between an anthropocentric world view, where humans are the center of concern, and an ecocentric (or biocentric) world view, where ecosystems, other species, and all life on Earth are deemed important.

Despite the efforts of preservationists such as John Muir, conservationism was predominantly anthropocentric because it emphasized the wise use of resources for human benefit. Similarly, environmentalism has also been largely anthropocentric in its emphasis on environmental quality as crucial for a high quality of human life. Concerns for human health, outdoor recreational opportunities, and an esthetically pleasing natural world were all motivated by an underlying concern with the welfare of humans—even though the natural environment often derived benefit from these concerns.

The recent emergence of ecologism, however, has broadened earlier concerns by incorporating an ecocentric world view stemming largely from two noteworthy branches of the modern movement: deep ecology and radical environmentalism (Devall 1992). Adherents of ecologism believe that nature has a right to exist in and of itself, apart from human desires. Although this position existed in the conservation movement via John Muir and his followers, and was given new impetus by Aldo Leopold’s ‘land ethic’ in the mid-1900s, only recently has it become a potent voice in the evolving movement. Advocates of ecologism hold as their primary goal the maintenance of ecological sustainability, for the entire earth and all of its inhabitants (Thiele 1999).

Social movements are further distinguished by the types of problems or issues that they address (their ‘grievances’). The issues addressed by environmental activists have expanded over time, as environmental problems and society’s awareness of them have grown. Not only has each stage seen new issues incorporated into a growing environmental agenda, but the issues themselves have been perceived quite differently over time. As modern technology and lifestyles have become more complex, the environmental problems they create have likewise increased in scale and complexity. Costs of solving environmental problems have also grown, reflecting a rapid change in the magnitude of the problems and our perceptions of them.

Conservationism typically dealt with specific and unambiguous issues, such as the protection of particular forestlands from logging. Compare this to air and water pollution, a typical concern of environmentalism. Pollution can diffuse over a broad area, its sources are often ambiguous, and its effects may be delayed and difficult to identify. In short, pollution is more subtle than logging, and controlling or stopping it is typically more difficult and costly.

Ecologism incorporates an even wider range of issues, as well as a significantly different perception of these issues. Especially notable is a greater emphasis on both micro and macro concerns. At the micro level, grassroots groups around the country are mobilizing NIMBY (‘Not-In-My-Backyard’) protests against garbage incinerators and hazardous waste sites. Minorities in particular are mobilizing against ‘environmental racism,’ the practice of locating environmentally noxious facilities in their communities. At the macro level, ecologism is concerned with issues of international import, such as global warming, ozone destruction, and the loss of rainforests. In addition, the growing radical wing of the movement, mentioned earlier, promotes an ecocentric world view and an emphasis on global ecological sustainability. In fact, radical groups such as Earth First!, as well as many of the grassroots groups, have developed explicitly in reaction to what they refer to as the ‘reform’ environmentalism and ‘shallow’ ecology embodied by the mainstream national environmental organizations.

These relatively new wings of the movement, while having some antecedents, reflect a qualitatively different approach to environmental issues. In fact, the major difference between ecologism and its forerunners is not so much in the types of issues it looks at, but rather in how it looks at them. Ecologism focuses on a bigger picture than either environmentalism or conservationism. Older issues such as concern for human health, and even the welfare of future generations, are important, but ecologism is marked by concern for overall ecological sustainability and recognition of the inherent interdependence of all life systems (Thiele 1999). Even NIMBYites are becoming concerned with the sustainability of current production systems, as witnessed by the growing NIABY (‘Not-In-Anyone’s-Backyard’) attitude. Ecologism thus broadens environmental concern in various ways, fighting on a greater number of fronts—from local to global—and viewing other species and ecosystems as having rights to exist independent of human interests. Concern for equity between species parallels a growth in concern for equity within the human race and across generations, as advocates of sustainable development attempt to rectify social injustice and poverty as well as environmental devastation throughout the world.

Ecologism entails an expanded critique of the status quo, based on a systemic and large-scale view of human impact on the natural environment. The pivotal concerns of ecologism are typically those that involve long-term, irreversible, synergistic, and often unpredictable consequences of human actions. Global warming and loss of biodiversity, for instance, are not only long-term and irreversible results of human actions, but they stem from an incredibly complex interplay of factors. While environmentalism has often addressed these issues, it has looked at them in a piecemeal fashion. Ecologism, on the other hand, views them in the context of the larger ecological– evolutionary global system. Advocates of ecologism talk about the end of nature, mass extinction, and the halt of evolution—unless human practices are altered, and soon. The purported causes and consequences, as well as the costs needed to remedy them, are therefore truly colossal.

A key aspect of social movements is the type of tactics they utilize. Just as the issues have broadened, so have the tactics employed by environmental activists. Tactically, conservationists relied heavily and successfully on lobbying government officials (epitomized by Pinchot’s influence with Teddy Roosevelt). The solution to resource problems, they felt, came with governmental and scientific management of resources. In addition to traditional lobbying, environmentalists added litigation, research, and citizen participation to their repertoire, through the development of researchand legal-oriented groups as well as via letter-writing campaigns and mass protests (Mitchell et al. 1992).

Ecologism builds upon this tactical legacy— grassroots activists march and petition government officials, organizations engage in litigation and lobbying—but it increasingly employs more aggressive tactics such as consumer boycotts and various forms of ‘direct action.’ The growing radical wing of the movement is especially likely to engage in sit-ins, ‘monkey-wrenching’ of equipment, and other forms of ‘ecotage’ (from pouring quick rice in the radiator of a bulldozer to ramming a drift-net ship on the high seas) that are disavowed by mainstream environmentalists intent on ‘working within the system’ in order to reform it.

Recent years have also seen a rapid growth in other forms of activism, such as electoral action. More and more organizations are becoming active in political campaigns, not only publicizing candidates’ records but publicly supporting selected candidates. In addition, advocates of ecologism, like their predecessors, promote lifestyle change, ranging from recycling and purchasing ‘green’ products, to reduced consumption and dietary changes. The tactics have clearly broadened and it is likely that they will continue to do so.

Finally, social movements can be distinguished by their opposition and the source of their grievances. Usually these are related, for those who benefit from environmentally harmful practices are most likely to oppose attempts to halt those practices. As our understanding of ecological problems has progressed, so has recognition of their embeddedness in the status quo. No longer are just a few ‘robber barons’ to blame for our problems; rather, as Pogo said: ‘We have met the enemy, and he is us.’

Conservationism laid the blame for resource depletion at the feet of a relatively small group of people, and thereby stimulated limited opposition. Environmentalism, in contrast, blamed entire industries, modern lifestyles, and ‘growthmania’ in general, and in the process engendered broader opposition. Ecologism issues a critique that leaves few unscathed, for our entire species and the status quo (at least within industrialized nations) are to blame, albeit some aspects more so than others. Simply reforming current practices via legislation is therefore unlikely to suffice. As a simple example, rather than favoring installation of scrubbers on factory smokestacks to reduce pollutants, advocates of ecologism argue for alternative production techniques or giving up the product completely. Because the economic and social costs of halting human-induced environmental change could prove enormous, and leave little of modern life untouched, ecologism has the potential to stimulate enormous opposition.

4. The Future

The recent emergence of ecologism reflects the persistent evolution of societal concern over the impact of humans on the Earth. Based on the staying power of environmentalism over the past few decades, it is likely that the current wave of ecologism will continue to be a vital force. A major reason for this optimism is the great diversity of ecologism. Just as biodiversity is vital to the stability of ecosystems, tactical and ideological diversity may be among ecologism’s greatest strengths. Still, given that ecologism has arisen out of frustration over the failure of environmentalism to halt ecological degradation, and given the immensity of the tasks (and opposition) it faces, the future for this latest phase of human efforts to protect the environment is uncertain. Ultimately, the true test of a social movement is its success in achieving its goals, not simply in maintaining its own survival.

Bibliography:

- Brulle R J 2000 Agency, Democracy and the Environment: The US Environmental Movement from the Perspective of Critical Theory. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Bullard R D (ed.) 1993 Confronting Environmental Racism: Voices from the Grassroots. South End Press, Boston

- Dalton R J 1994 The Green Rainbow: Environmental Groups in Western Europe. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT

- Devall B 1992 Deep ecology and radical environmentalism. In: Dunlap R E, Mertig A G (eds.) American Environmentalism: The US Environmental Movement, 1970–1990. Taylor and Francis, Philadelphia, PA, pp. 51–62

- Dunlap R E 1995 Public opinion and environmental policy. In: Lester J P (ed.) Environmental Politics and Policy, 2nd edn. Duke University Press, Durham, NC, pp. 63–113

- Dunlap R E 2000 The environmental movement at 30. The Polling Report 16(1): 6–8

- Dunlap R E, Mertig A G 1995 Global concern for the environment: Is affluence a prerequisite? Journal of Social Issues 51(4): 121–137

- Guha R, Martinez-Alier J 1997 Varieties of Environmentalism: Essays North and South. Earthscan, London

- Hays S P 1959 Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890–1920. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Hays S P 1987 Beauty, Health and Permanence: Environmental Politics in the United States, 1955–1985. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Mitchell R C, Mertig A G, Dunlap R E 1992 Twenty years of environmental mobilization: Trends among national environmental organizations. In: Dunlap R E, Mertig A G (eds.) American Environmentalism: The US Environmental Movement, 1970–1990. Taylor and Francis, Philadelphia, pp. 11–26

- Nash R 1982 Wilderness and the American Mind, 3rd edn. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT

- Rootes C A 1997 Environmental movements and Green parties in Western and Eastern Europe. In: Redclift M, Woodgate G (eds.) The International Handbook of Environmental Sociology. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, pp. 319–48

- Rowell A 1996 Green Backlash: Global Subversion of the Environmental Movement. Routledge, London

- Switzer J V 1997 Green Backlash: The History and Politics of Environmental Opposition in the US. Lynne Reinner, Boulder, CO

- Taylor D E 1998 The urban environment: The intersection of white middle-class and white working-class environmentalism (1820–1950s). Advances in Human Ecology 7: 207–92

- Thiele L P 1999 Environmentalism for a New Millennium: The Challenge of Coevolution. Oxford University Press, New York