Sample Environmental Justice Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, chech our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Despite significant improvements in environmental protection over the last quarter of the twentieth century, millions of Americans continue to live in unsafe and unhealthy physical environments. Hardly a day passes without the media discovering some community or neighborhood fighting a landfill, incinerator, chemical plant, or some other polluting industry. This was not always the case. In the 1970s, the concept of environmental justice had not registered on the radar screens of environmental, civil rights, or social justice groups. Nevertheless, it should not be forgotten that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. went to Memphis in 1968 on an environmental and economic justice mission for the striking black garbage workers. The strikers were demanding equal pay and better working condition. Of course, Dr. King was assassinated before he could complete his mission.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Birth Of A New Movement

The national environmental justice movement emerged around the issues of fairness, social equity, and environmental protection. This new movement embraces the principle that all communities are entitled to equal protection and enforcement of environmental, health, employment, housing, transportation, and civil rights laws and regulations that impact quality of life. The environmental justice framework rests on developing tools and strategies to eliminate unfair, unjust, and inequitable conditions and decisions. The framework also attempts to uncover the underlying assumptions that may contribute to and produce differential exposure and unequal protection. It brings to the surface the ethical and political questions of ‘who gets what, when, why, and how much’ (Bullard 1996). The national environmental justice movement framework has its origins in the United States of America.

1.1 Definition Of Environmental Justice

Environmental justice is defined as the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. Fair treatment means that no group of people, including racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic groups should bear a disproportionate share of the negative environmental consequences resulting from industrial, municipal, and commercial operations or the execution of federal, state, local, and tribal programs and policies (US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) 1998).

1.2 Early Struggles

Another landmark garbage dispute took place in Houston, Texas, a decade after the Memphis garbage strike. African–American homeowners in Houston began a bitter fight to keep the Whispering Pines sanitary landfill out of their suburban middle-income neighborhood. The residents formed the Northeast Community Action Group or NECAG. In 1979, NECAG and their attorney, Linda McKeever Bullard, filed a class action lawsuit to block the garbage facility from being built. The 1979 lawsuit, Bean vs. Southwestern Waste Management, Inc., was the first of its kind to challenge the siting of a waste facility under civil rights law.

The landmark Houston case occurred three years before the environmental justice movement was catapulted into the national limelight in the rural and mostly African–American Warren County, North Carolina. The environmental justice movement has come a long ways since its humble beginning in Warren County where a hazardous-waste landfill ignited protests and over 500 arrests. This marked the first time Americans had been arrested protesting the siting of a waste facility.

The Warren County protests provided the impetus for US General Accounting Office to conduct an independent investigation. That study revealed that three out of four of the off-site, commercial hazardous waste landfills in Region 4 (which comprises eight states in the South) were located in predominantly African–American communities, although African– Americans made up only 20 percent of the region’s population (US General Accounting Office 1983). Nearly 15 years later, the state of North Carolina committed over $25 million to cleanup and detoxify the controversial Warren County landfill.

The protests also led the Commission for Racial Justice (1987) to produce Toxic Waste and Race, the first national study to correlate waste facility sites with demographic characteristics. Race was found to be the most potent variable in predicting where these facilities were located—more powerful than poverty, land values, and home ownership or occupancy status.

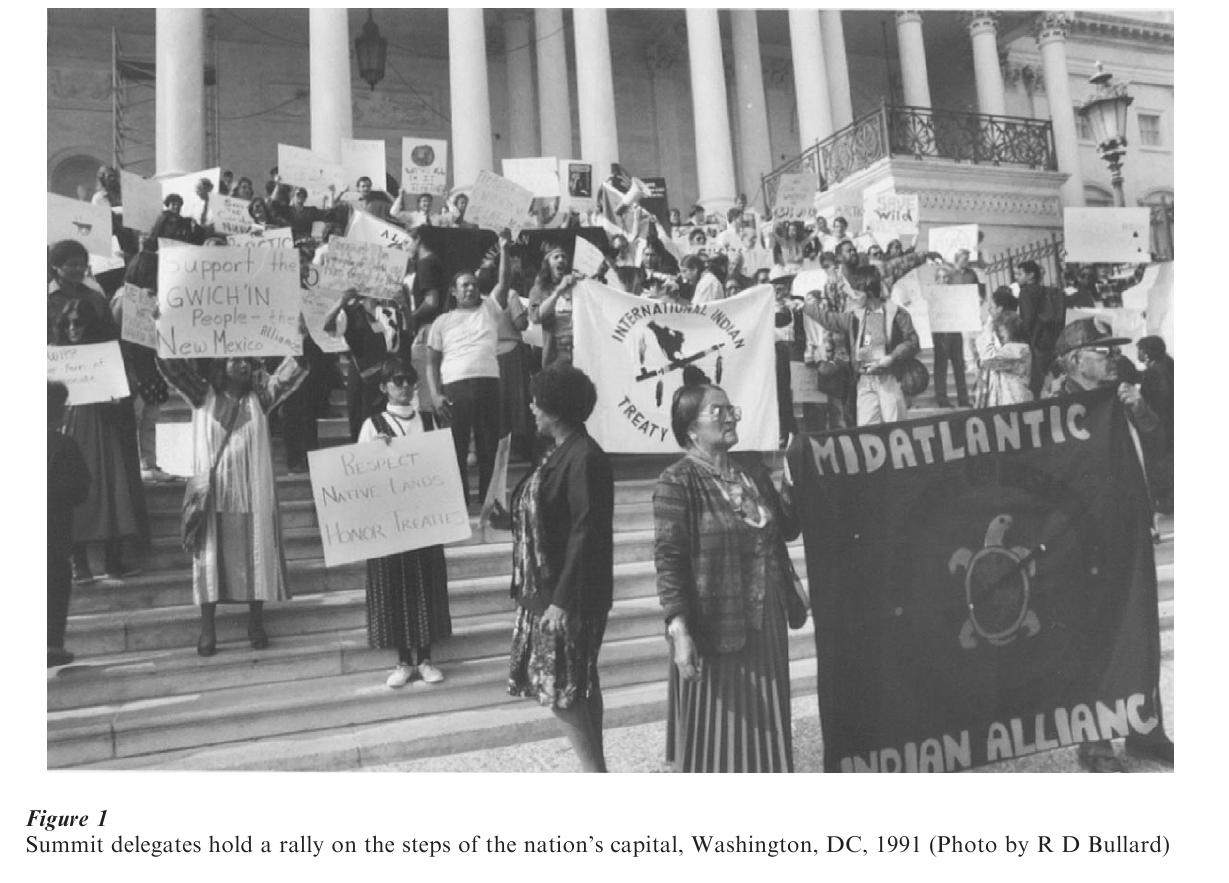

1.3 The People Of Color Summit

The 1991 First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit was probably the most important single event in the young movement’s history. Held in Washington, DC, the 4-day Summit was attended by over 650 grassroots and national leaders from around the world. Delegates came from all 50 states including Alaska and Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Chile, Mexico, and as far away as the Marshall Islands (Fig. 1).

The Summit broadened the environmental justice movement beyond its anti-toxics focus and demonstrated that it is possible to build a multiracial grassroots movement around environmental and economic justice. On September 27, 1991, Summit delegates adopted 17 ‘Principles of Environmental Justice.’ By June 1992, Spanish and Portuguese translations of the Principles were being used and circulated by NGOs and environmental justice groups at the Earth Summit and Global Forum in Rio de Janeiro.

2. Government Response

The federal EPA manages, regulates, and distributes risks. During its 30-year history, the EPA has not always recognized that many government and industry practices (whether intended or unintended) have adverse impact on poor people and people of color. In 1992, after meeting with community leaders, academicians, and civil rights leaders, the EPA (under the Bush Administration) admitted there was a problem, and established the Office of Environmental Equity. The name was changed to the Office of Environmental Justice under the Clinton Administration.

The agency produced Environmental Equity: Reducing Risks for All Communities, a comprehensive report that examines environmental justice concerns in low-income and people of color communities (US Environmental Protection Agency 1992). The EPA also established a 25-member National Environmental Justice Advisory Council or NEJAC under the Federal Advisory Committee Act. The NEJAC is comprised of stakeholders representing grassroots community groups, environmental groups, nongovernmental organizations, state, local, and tribal governments, academia, and industry.

2.1 Environmental Justice Health Symposium

In February, 1994, seven federal agencies, including the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Energy (DOE), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sponsored a national health symposium, ‘Health and Research Needs to Ensure Environmental Justice.’ The February conference was attended by more than 1,000 scientists, researchers, health professionals, educators, government officials, and community stakeholders.

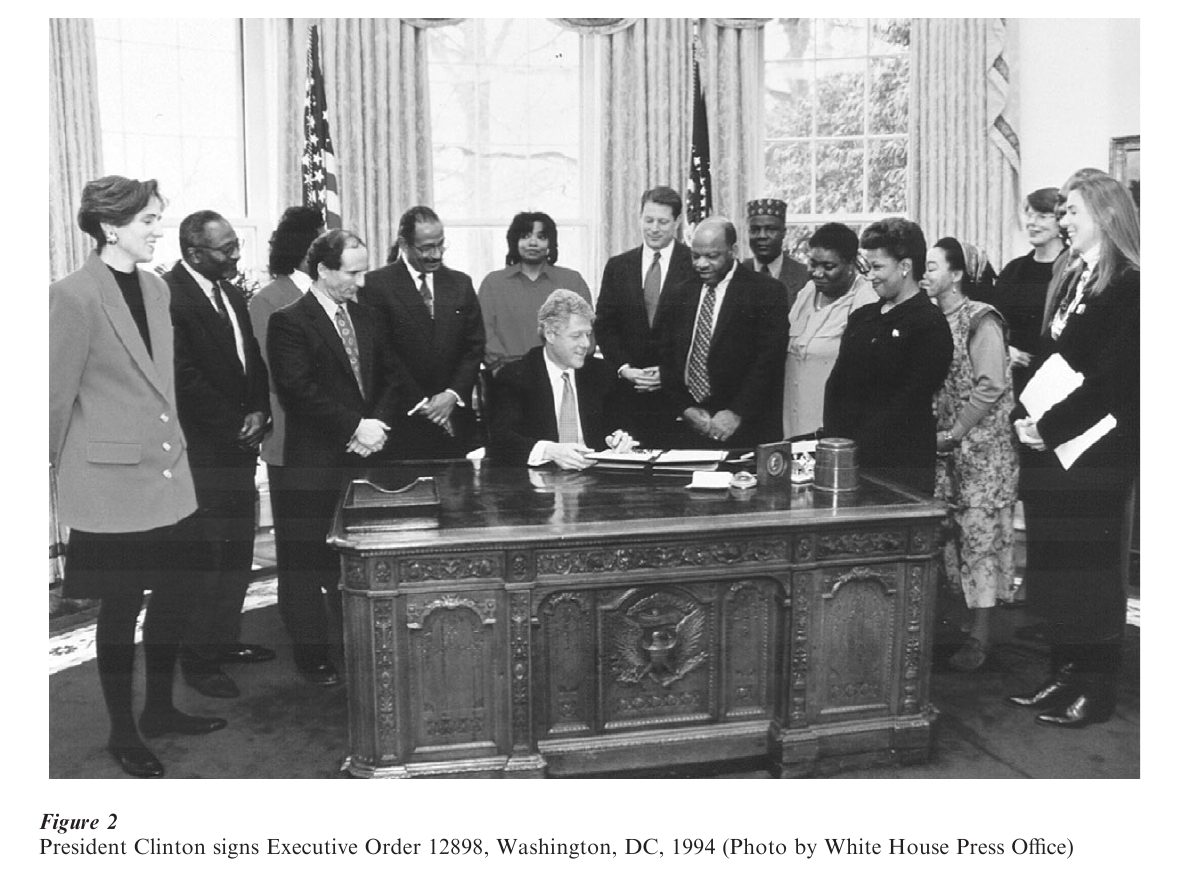

Environmental justice leaders offered their own environmental protection framework. This framework adopts a public health model of prevention (i.e., elimination of the threat before harm occurs) as the preferred strategy, shifts the burden of proof to polluters dischargers who do harm, who discriminate, or who do not give equal protection to people of color, low-income persons, and other ‘protected’ classes, allows disparate impact and statistical weight or an ‘effect’ test, as opposed to ‘intent,’ to infer discrimination, and redresses disproportionate impact through ‘targeted’ action and resources (Fig. 2).

2.2 Executive Order 12898

In response to growing public concern and mounting scientific evidence, President Clinton on February 11, 1994 issued Executive Order 12898, ‘Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations.’ The Order attempts to address environmental injustice within existing federal laws and regulations. It reinforces the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VI, which prohibits discriminatory practices in programs receiving federal funds. The Order also focuses the spotlight back on the 1969 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), a law to ensure for all Americans a safe, healthful, productive, and aesthetically and culturally pleasing environment (Council on Environmental Quality 1997).

3. Communities Under Siege

A growing body of evidence reveals that people of color and low-income persons have borne greater environmental and health risks than the society at large in their neighborhoods, workplace, and playgrounds (Bryant 1995, Bullard 1999a, 1999b, 1999c, 2000, Stretesky and Hogan 1998). A recent study from the Institute of Medicine (1999) concluded that government, public health officials, and the medical and scientific communities need to place a higher value on the problems and concerns of environmental justice communities. The IOM study confirmed what most impacted communities have known for decades. People of color and low-income communities are (a) exposed to higher levels of pollution than the rest of the nation, and (b) experience certain diseases in greater numbers than the more affluent, white communities (Institute of Medicine 1999).

3.1 Unequal Protection

The National Law Journal uncovered glaring inequities in the way the federal EPA enforces its giant Superfund

laws. White communities see faster action, better results, and stiffer penalties than communities where blacks, Hispanics, and other people of color live (Lavelle and Coyle 1992). Clearly, communities that are located on the ‘wrong side of the tracks’ are at special risk from exposure to environmental hazards. Race has been found to be independent of class in the distribution of air pollution, contaminated fish consumption, location of municipal landfills and incinerators, abandoned toxic waste dumps, polluting industries, and lead poisoning in children (Commission for Racial Justice 1987, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry 1988, Pirkle et al. 1994).

3.2 Childhood Lead Poisoning

Lead poisoning is the number one environmental health threat to children of color. Figures reported in the July 1994 Journal of the American Medical Association on the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) revealed that 1.7 million children (8.9 percent of children aged 1 to 5) are lead poisoned, defined as blood lead levels equal to or above 10 micrograms deciliter. The NHANES III data found African–American children to be lead poisoned at more than twice the rate of white children at every income level (Pirkle et al. 1994). Over 28.4 percent of all low-income African–American children were lead poisoned compared to 9.8 percent of low-income white children. During 1976–1991, the decrease in blood lead levels for African–American and Mexican–American children lagged far behind that of white children.

In California, a coalition of environmental, social justice, and civil libertarian groups joined forces to challenge the way the state carried out its lead screening of poor children. The Natural Resources Defense Council, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Legal Defense and Education Fund (NAACP LDF), the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Legal Aid Society of Alameda County, California won an out-of-court settlement worth $15 million to $20 million for a blood lead-testing program. The lawsuit, Matthews vs. Coye, involved the failure of the state of California to conduct federally mandated testing for lead of some 557,000 poor children who receive Medicaid. This historic agreement triggered similar lawsuits in several other states that failed to live up to the federal mandates.

4. The Path Of Least Resistance

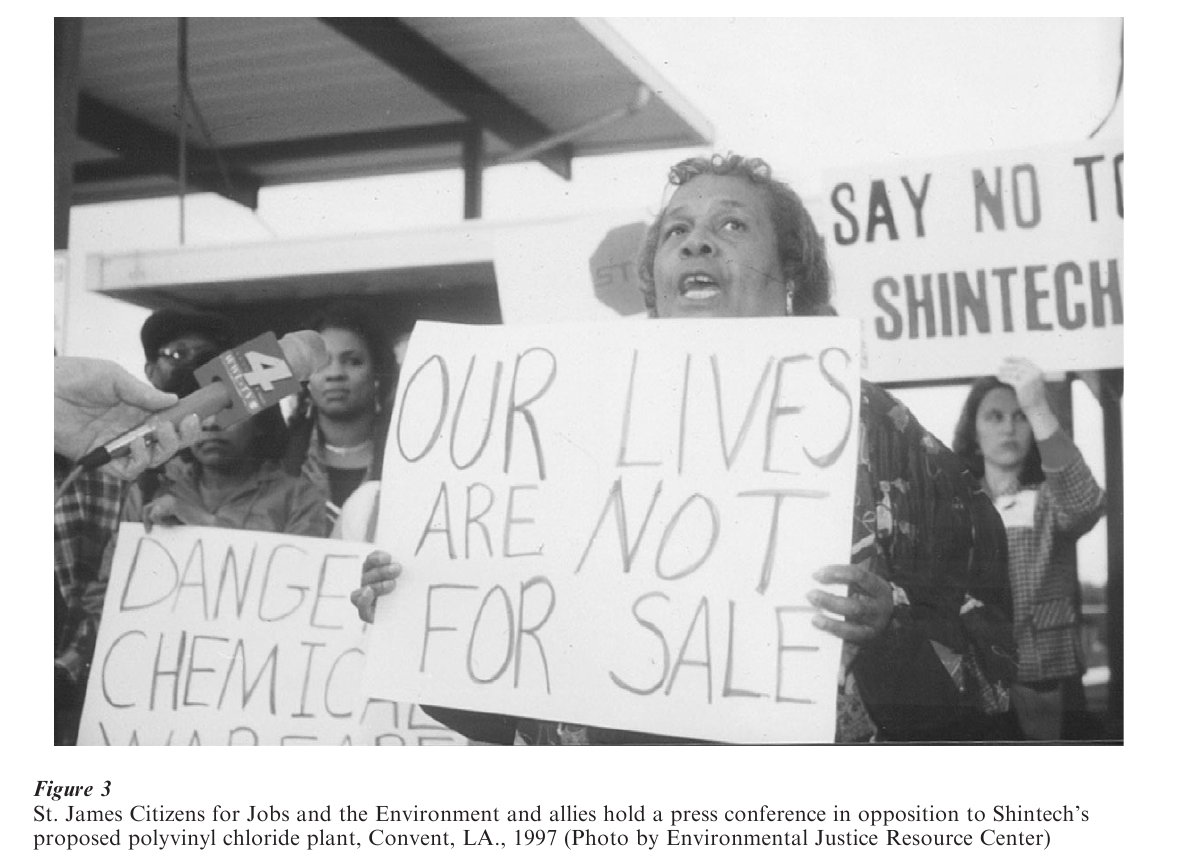

The southern US has become a ‘sacrifice zone’ for the rest of the nation’s toxic waste. Lax enforcement of environmental regulations has left the region’s air, water, and land the most industry-befouled in the US. Louisiana typifies this pattern. Nearly three-fourths of Louisiana’s population, more than 3 million people, get their drinking water from underground aquifers. Dozens of aquifers are threatened by contamination from polluting industries. The Lower Mississippi River Industrial Corridor has over 125 companies that manufacture a range of products including fertilizers, gasoline, paints, and plastics. Environmentalists and local residents have dubbed this corridor ‘Cancer Alley’ (Motavalli 1998, Bullard 2000).

4.1 Corporate Welfare

Louisiana is also a leader in doling out corporate welfare to polluters. Industries routinely pollute the air, ground, and drinking water while being subsidized by tax breaks from the state. In the 1990s, the state wiped off the books $3.1 billion in property taxes to polluting companies. The state’s top five worse polluters received $111 million dollars over the past decade (Barlett and Steele 1998) (Fig. 3).

Subsidizing polluters is not only bad business, but it does not make environmental sense. A growing body of evidence reveals that ‘states with lower pollution levels and better environmental policies generally have more jobs, better socioeconomic conditions and are more attractive to new businesses’ (Templet 1995). Louisiana and other states could actually improve their general welfare by enacting and enforcing regulations to protect the environment.

4.2 Dumping On Native Americans

It should not be a surprise to anyone to discover that Native Americans have to contend with some of the worst pollution in the US (Tomsho 1990, Taliman 1992). Native American nations are prime targets for waste trading. More than three dozen Indian reservations were targeted for landfills, incinerators, and other waste facilities in the early 1990s. Native American groups and their allies defeated most of these waste proposals.

Racism operates in energy production (mining of uranium) and disposal of wastes on Indian lands (Churchill and LaDuke 1983). The practice has left many sovereign Indian nations without an economic infrastructure to address poverty, unemployment, inadequate education and health care, and a host of other social problems. In 1999, residents of the Eastern Navajo reservation filed suit with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to block a permit for uranium mining in Church Rock and Crown Point, New Mexico.

4.3 Transboundary Waste Trade

Hazardous waste generation and international movement of hazardous waste pose some important health, environmental, legal, and ethical dilemmas. Shipping hazardous wastes from rich communities to poor communities is a global problem. In the real world, all people, communities, and nations are not created equal. Unequal interests and power arrangements have allowed poisons of the rich to be offered as short-term remedies for poverty of the poor. This scenario plays out domestically (as in the US where low-income and people of color communities are disproportionately impacted by waste facilities and ‘dirty’ industries) and internationally (where hazardous wastes move from OECD states to non-OECD states).

The conditions surrounding the more than 2,000 maquiladoras, assembly plants operated by American, Japanese, and other foreign countries, located along the 2,000-mile US–Mexico border may further exacerbate the waste trade. The industrial plants use cheap Mexican labor to assemble imported components and raw material and then ship finished products back to the US. Nearly a half million Mexican workers are employed in the maquiladoras. All along the Lower Rio Grande River Valley maquiladoras dump their toxic wastes into the river, from which 95 percent of the region’s residents get their drinking water (Hernandez 1993). In the border cities of Brownsville, Texas and Matamoras, Mexico, the rate of anencephaly—babies born without brains —is four times the national average. Affected families have filed lawsuits against 88 of the area’s 100 maquiladoras for exposing the community to xylene, a cleaning solvent that can cause brain hemorrhages, and lung and kidney damage.

The Mexican environmental regulatory agency is understaffed and not equipped adequately to address the problem (Barry and Simms 1994). Only time will tell if the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) will ‘fix’ or exacerbate the economic, public health, and the environmental problems along the US–Mexico border.

5. Conclusion

The environmental justice movement emerged in response to environmental and social inequities, threats to public health, unequal protection, differential enforcement, and disparate treatment received by the poor and people of color. The movement redefined environmental protection as a basic right. It also emphasized pollution prevention, waste minimization, and cleaner production techniques as strategies to achieve environmental justice for all Americans without regard to race, color, national origin, or income.

The poisoning of African–Americans in Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley,’ Native Americans on reservations, and Mexicans in the border towns all have their roots in a system characterized by economic exploitation, racial oppression, and devaluation of human life and the natural environment. Unequal political power arrangements have allowed poisons of the rich to be offered as short term economic remedies for poverty and unemployment. Having industrial facilities in one’s community does not automatically translate into jobs for nearby residents. Similarly, tax breaks and corporate welfare programs have produced few new jobs by polluting firms.

The environmental justice movement has established clear goals of eliminating unequal protection. This call for environmental and economic justice does not stop at the US borders but extends to communities and nations that are threatened by the export of hazardous wastes, toxic products, and ‘dirty’ industries. Environmental justice leaders are demanding that no community or nation, rich or poor, urban or suburban, black or white, should be allowed to become a ‘sacrifice zone’ or dumping grounds. They are also pressing governments to live up to their mandate of protecting public health and the environment.

Bibliography:

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry 1988 The Nature and Extent of Lead Poisoning in Children in the United States: A Report to Congress. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA

- Barlett D L, Steele J B 1998 Paying a price for polluters. Time (November 23): 72–80

- Barry T, Simms B 1994 The Challenge of Cross Border Environmentalism: The US–Mexico Case, 1st edn. Resource Center Press, Albuquerque, NM

- Bryant B 1995 Environmental Justice: Issues, Policies, and Solutions. Island Press, Washington, DC

- Bullard R D (ed.) 1996 Unequal Protection: Environmental Justice and Communities of Color. Sierra Club Books, San Francisco

- Bullard R D 1999 a Dismantling environmentalism in the USA. Local Environment 4: 5–19

- Bullard R D 1999 b Building just, safe, and healthy communities. Tulane Environmental Journal 12: 373–404

- Bullard R D 1999 c Leveling the playing field through environmental justice. Vermont Law Review 23(Spring): 454–78

- Bullard R D 2000 Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class and Environmental Quality, 3rd edn. Westview Press, Boulder, CO

- Churchill W, LaDuke W 1983 Native American: The political economy of radioactive colonialism. Insurgent Sociologist 13(1): 51–63

- Commission for Racial Justice 1987 Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States. Public Data Access, New York

- Council on Environmental Quality 1997 Environmental Justice: Guidance under the National Environmental Policy Act. CEQ,Washington, DC

- Hernandez B J 1993 Dirty Growth The New Internationalist August

- Institute of Medicine 1999 Toward Environmental Justice: Research, Education, and Health Policy Needs. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

- Lavelle M, Coyle M 1992 Unequal protection. The National Law Journal September 21: 1–2

- Motavalli J 1998 Toxic targets: Polluters that dump on communities of color are finally being brought to justice. E Magazine 9 (July/August): 28–41

- Pirkle J L, Brody D J, Gunter E W, Kramer R A, Paschal D C, Glegal K M, Matte T D 1994 The decline in blood lead levels in the United States: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Journal of the American Medical Association 272: 284–291

- Stretesky P, Hogan M J 1998 Environmental justice: An analysis of superfund sites in Florida. Social Problems 45(May): 268–87

- Taliman V 1992 Stuck holding the nation’s nuclear waste. Race, Poverty & Environment Newsletter (Fall): 6–9

- Templet P H 1995 The positive relationship between jobs, environment and the economy: An empirical analysis and review. Spectrum (Spring): 37–49

- Tomsho R 1990 Dumping grounds: Indian tribes contend with some of the worst of America’s pollution. The Wall Street Journal (November 29)

- US General Accounting Office 1983 Siting of Hazardous Waste Landfills and Their Correlation with Racial and Economic Status of Surrounding Communities. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

- US Environmental Protection Agency 1992 Environmental Equity: Reducing Risk for All Communities. EPA, Washington, DC

- US Environmental Protection Agency 1998 Guidance for Incorporating Environmental Justice in EPA’s NEPA Compliance Analysis. EPA, Washington, DC