Sample Farmland Preservation Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

One might think that the escalation of the world’s population and widespread famine would supply an ample reason for the preservation of agricultural land in the better-off countries where agricultural production is also the most know-how-intensive and efficient. But in fact, wherever conversion to urban development is more lucrative than the income from farming, agricultural land is in danger of losing out, unless special public policies are installed. This almost axiomatic conflict means that farmland preservation is a concern of every industrialized country. The relentless expansive energy of cities often affects precisely those areas that are most attractive to farming.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

But despite the importance of preserving agricultural land from a worldwide perspective, the stimulus for farmland preservation in advanced economy countries is increasingly tilting away from concerns about agricultural production per se, towards environmental, landscape heritage, and quality of life concerns for the urban residents. Bruce (1998) shows how the interests and needs of the farmers themselves have receded almost to disappearance in the discourse about farmland preservation, while environmental and quality of life goals have risen. Moreover: the very goal of preserving farmland is not beyond dispute. It is sometimes challenged by competing goals, some stemming from the changing economics of particular types of agriculture, others from social equity policies or overriding national priorities, such as the supply to affordable housing. In the countries across the Atlantic, such goal conflicts are more intense than in North America.

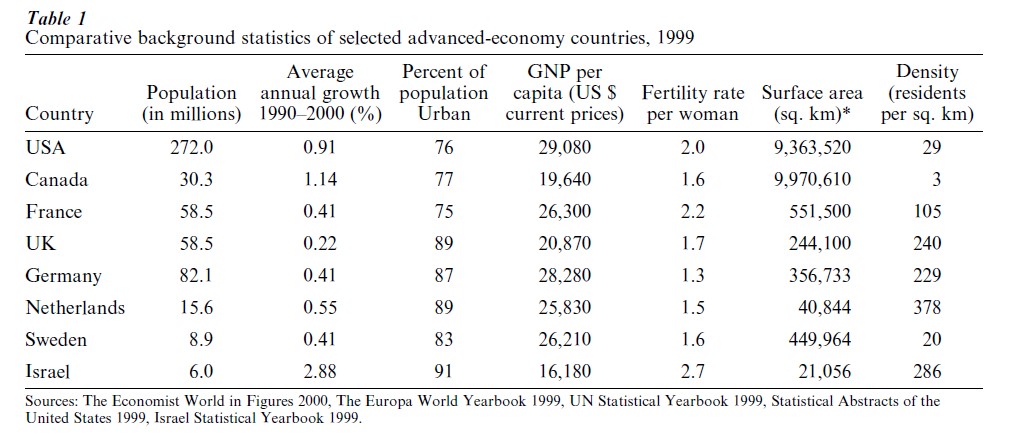

Beyond the shared characteristics among advanced economy countries, there are significant differences in the specific goals and means for farmland preservation and in the degree of success achieved. While focusing mostly on the USA, this research paper takes a cross-national view of farmland preservation goals, means, and outcomes in selected advanced economy countries (see Table 1). The author bases this research paper on research about farmland preservation laws, policies, contexts, and degrees of success in the USA, Canada, the UK, France, The Netherlands, and Israel, and in more general terms, also Germany and Sweden. For a detailed exposition see Alterman (1997).

1. Comparing The Contexts

The conflict over land use has much to do with degree of urbanization, economic well-being, population growth, and population density. In the advanced economy countries, where the Gross Domestic Product per person is relatively high, growing food for subsistence is not a major problem because there is enough wealth to supplement what is locally grown with imported food. Local food self-sufficiency is not yet an item on the agenda of most local land-use planning agencies, though some have argued that it should be (see Pothukuchi and Kaufman 2000). As a group, these countries contrast sharply with less developed countries or East European countries, where the figures for annual GDP per person would typically run in the hundreds or very few thousands. The advanced economy countries also differ significantly among themselves (see Table 1).

The USA and Canada are large countries and less densely inhabited than most European countries. In view of their sophisticated farming technology and know-how, the USA and Canada not only supply most of their internal needs for food and fiber, they are major food exporters on which many other countries depend. While these two countries share some aspects of farmland policies, they differ on others. Canada has by far the lowest population density among the countries surveyed. The US population density of 27 per square km, and Canada’s 3 (only Australia and Iceland are Western countries with similar densities), are low compared to most countries across the Atlantic. Although most of Canada’s land area is quite inhospitable climatically and its 8 percent agricultural land is concentrated along a thin strip along the US border, the area of farmland per Canadian is considerably higher than in the US.

Crossing the Atlantic brings us to a different world of generally smaller farms than in the USA or Canada, much higher population densities, and distinctly more compact cities. France, with a lower population density than most continental European countries, has 105 persons per square km, while at the other extreme The Netherlands has 378 persons. Israel, though currently less densely inhabited than the Netherlands, is in the long term the densest because it has the highest population growth and fertility rates among advanced economy countries.

Even though it has less farmland per person than North America, Western Europe faces a reverse problem: agricultural surpluses endanger the maintenance of price levels and have led the European Union to adopt policies of compulsory ‘set asides’ of farmland. These pose a clear challenge to the very notions of farmland preservation.

There is no agreement cross-nationally about the size of farming units that should be the target for preservation. In the USA, hobby farming by wealthy ex-urbanites is regarded as a threat to commercial farming. Europeans, who are concerned more with preserving the visual and environmental character of the traditional countryside, tend to focus more on encouraging ‘family farms.’ Although there is also a concern in the USA with supporting the family farm, the status of such farms is probably more secure there than across the Atlantic in view of the much-larger average size of American family farms.

2. How Public Awareness And Planning Policies Emerged

In both the USA and Canada, farmland preservation gained public support only in the 1980s; later than in most Western European countries. The landmark US National Agricultural Lands Study published in 1981 arose out of this growing concern and propelled it further. That study found that farmland conversion increased almost three-fold between the 1960 and the 1970s, rising from 1.1 million acres a year in the 1960s to 3 million acres a year in the 1970s. In Canada, policymakers’ awareness about the depletion of farmland came approximately at the same time as the USA, and the major provincial programs, Ontario, British Columbia, and later Quebec, ensued (Reid and Yeates 1991).

In the USA and Canada, policies and methods for farmland preservation were a relative novice to the land-use planning and implementation kit of tools. No prescriptive formulae with proven results existed in the professional literature or in practice. Farmland preservation was not part of the routine work of local or state governments; someone had to ‘invent’ them. In the USA, the process whereby these tools emerged and tested (which, incidentally, is quite typical of other areas of land-use planning and implementation) may be called a ‘survival of the fittest’ process whereby more successful local policies survive and gain national recognition. While such policies were being developed and disseminated sporadically across local and state authorities in the 1980s, several ‘how to’ publications appeared that collated the emerging ‘kit of tools’ for planners and decision makers (for a listing of these see Alterman 1997). Scholarly evaluation of the degrees of success and impacts of alternative techniques has taken longer, and the jury is still out about some of them. In the Western European and Israeli context, where regional and national land-use planning is generally better entrenched in national legislation and tradition (for a comparative analysis of the broader land-use planning contexts in these countries see Alterman 2001), farmland preservation methods may therefore have been more ‘natural.’ That is not to say that they were more successful. Along with the general de-legitimization of direct government intervention, gradual changes occurred in the type of tools used for farmland preservation.

The other side of the coin of farmland preservation is containment of urban development and prevention of sprawl. This concern arrived in the USA and Canada much later than across the Atlantic where compact cities are the tradition. American planners had to invent a special term, ‘growth management’ (and since the mid 1990s, also ‘smart growth’) to discuss what is a routine part of land-use planning in much of Europe. ‘Growth management’ describes an open-ended set of policies and methods to phase and control the growth of cities and suburbs and to rationalize infrastructure investments. This approach often also prescribes a more coordinated institutional structure for land-use and fiscal planning (several of many titles on growth management include De Grove 1992, Stein 1993, Daniels 1999. A full review of growth management and ‘smart growth’ law and policy is presented by I Kushner 2000). However, only a minority of US states has seriously adopted growth management policies and tools.

3. Farmland Preservation Policies

With 50 states and innumerable localities, generalization about US policies is difficult. When compared with the other countries surveyed, American farmland preservation policies are characterized by a rich variety, innovativeness, and capacity for experimentation, but usually with only lukewarm effects.

A distinctive attribute of American farmland preservation policies is that planners and policymakers usually view them as a package of tools that cut across policy areas. By contrast, in some of the countries across the Atlantic, there is or was a dominant method of preservation usually based on top-down control that restricted the authority of lower-level governments to grant permits for conversion of farmland. The American-style package of tools offers not only land-use controls directly regulating the conversion of farmland to development, but also a variety of other tools such as taxation and developer exactions.

Direct control of land-use conversion from farming to non-farming use seems to be the most intuitively obvious tool. However, it does not hold center stage in the USA except in a few states, foremost Hawaii and oregon. The most stringent version, called ‘exclusive zoning,’ restricts all uses of land except for farming or farming-related construction, but it is the least common of farmland preservation tool in the USA (Coughlin 1991, American Farmland Trust 1997). It is more prevalent in the countries cross the Atlantic, and ostensibly the most restrictive in Israel. In all the countries studied, exclusive zoning has been receding in importance and effectiveness. Yet in Oregon, where it is a major tool and is applied on a statewide level through a state institution, it has been found to be reasonably successful (Howe 1993, Nelson 1992). Much more common across the USA is a more flexible form of farmland conversion control, called ‘nonexclusive zoning.’ It permits many other land uses and puts few hurdles before conversion. Usually applied on the local and county levels only, its effect is often quite lukewarm (Coughlin 1991).

Another direct control method that is so characteristics of British and some other Western European land-use policies is an effectively regulated ‘greenbelt’ around urban areas (an in-depth analysis of British greenbelt policies and their effectiveness is by Elson et al. This approach is not as common or effectively used in the USA. For example, the city of Madison, a midsize Midwest city, discussed such a concept but interpreted it as the designation of several narrow one to three-mile buffers in a few spots along the circumference to be used as golf courses.

The dominant tools for farmland preservation in the USA are those that focus on the economics of conversion rather than seeking to limit the permission to build directly. These tools hope to defer the time when farming will no longer out-power real estate, but not to prevent it altogether. Among the most common are property or other tax relief programs such as existing use appraisal rules (where farming land is assessed for its value for agriculture, even if its real estate value has risen steeply). Also common are tax deferral programs, sometimes associated, as in Wisconsin, with agreements drawn with developers to continue farming for a preset number of years. Most widely used by all states are the so-called ‘right to farm’ laws that provide farmers immunity from lawsuits for causing a nuisance related to agricultural work. However, fiscal means are only mildly effective because once farmers feel that it is lucrative to sell, they do not deter conversions (see Nelson 1992).

Another economic tool, minimum lot size ordinances, aims to discourage suburban housing and thus defer conversion by making the land too costly for most population groups. However, research findings have shown that it is difficult to determine what is a viable cutoff line (Nelson 1992). Florida’s infrastructure concurrency requirements are intended to render development in outlying areas less lucrative, but in fact at times work in the reverse.

Property-rights based tools (for which the USA is probably the world leader) are a promising set that attempt to prevent development by buying up the very right to develop, or in effect, by compensating for the farmer’s willingness to forgo the opportunity for development. These include ‘land trusts’ by public agencies or, most commonly, voluntary sector organizations that purchase the development rights or easements from farmers while farmers retain the right to continue farming (Endicott 1993, American Farmland Trust 1997). Transfer of development rights is potentially a superb ‘made in America’ tool. In an area targeted for preservation, development rights are ‘purchased’ by landowners in another area, tagged a ‘receiving area,’ who wish to increase their development rights. However, research has shown that this tool can be used only in very particular market and land-use situations, otherwise, it is ineffective (see Pruetz 1997). A simpler tool that can be effective in some situations is cluster zoning whereby development rights are concentrated in one part of a larger land area (see Daniels 1998). Significant in their absence from the typical USA package of tools (but used very selectively in the other countries studied) are those whereby governments directly intervene in land tenure. They do this either through expropriation (‘condemnation’) of land, consolidation of lots that are too small for viable agriculture ( prevalent in France), redistribution of lots that are too large, or most ambitiously, ‘land readjustment’ that redistributes development rights more justly while preserving targeted land (used in Israel in spot cases). Also rare in the USA but prevalent in The Netherlands is land banking as an instrument for timing the conversion of farmland.

4. Levels Of Government And Legal Constraints

An important variable in the effectiveness of farmland preservation efforts is the level of government involved. From an international point of view, the USA stands out in the extreme degree of freedom held by local governments in most US states. Despite the ‘smart growth’ movement that has called for greater state action on land management, in most states, especially those in the heartland, the fate of farmland is still largely in the hands of local government or local civic groups. An important factor is the extensive self-incorporation and annexation powers held by local residents and local governments in many states. A majority of landowners in a particular tract of land who wish to annex themselves to an urban jurisdiction can initiate such a procedure. Although an urban municipality is empowered to refrain from rezoning agricultural land, local interests often achieve both annexations and rezoning.

In a few states, often called the ‘growth management’ states, the state government does play a major role in farmland preservation. Oregon, recognized as the flagship state for preservation, has developed an especially rich package of policies. Compared with the national rate of farmland conversion, Oregon has been quite successful through a combination of exclusive agricultural zones implemented by a special state-level commission, alongside policies for containing urban growth. But even this comparative success is limited to only a few farm-size categories, not all (as shown by Nelson 1992, Howe 1993). Hawaii is a second flagship state. It is unique in that it has full statewide zoning, including agricultural, that covers approximately half the state. But Hawaii has been only mildly successful in preventing conversions to urban use and, indeed, the conversion rate has doubled as the farm economy faltered (Callies 1994 describes the Hawaiian system of land-use controls. Empirical findings can be found in Ferguson and Khan 1992). Most states do not have state-level agricultural zoning. The Wisconsin tax relief and agreements program, while less illustrious than Oregon and Hawaii’s, is a more typical degree of state involvement. Research into its implementation in Dane County shows little effectiveness and rampant circumvention.

What of the US federal level? National-level involvement in farmland conservation in the USA has been strikingly weak when compared with other environmental areas such as air, water, wildlife, coastlines, and other environmental areas. An attempt to enact a Federal Land Use Act was aborted in the 1970s and never reattempted (see Kayden 2001). The almost nonexistent federal role in farmland preservation (on the books is the US Farmland Protection Policy Act of 1981 oriented to minimizing the extent to which projects initiated by the federal government contribute to farmland conversion, but it has been called ‘another case of benign neglect’ because of its failure in implementation; see Ward 1991) contrasts with the UK, The Netherlands, and Israel (but interestingly, not France), where legislation has given central government a major role (however, the contents of the preservation goals themselves are changing across the Atlantic as well; see Alterman 1997).

A major legal impediment to farmland preservation would be if a designation of land for farming use were to be legal grounds to claim compensation from government. In none of the countries studied across the Atlantic would denial of an application to convert farmland currently designated as agriculture constitute a good ground for claiming compensation. The USA is a possible exception, but even there, the likelihood of a successful claim is very small. The inherent fear of all American planners is the ‘taking issue’: the constitutional limitation on excessive regulation that might be ruled by the courts to be tantamount to a taking of property without just compensation. Since the law on this issue in the USA is perpetually inconclusive and farmland preservation has not yet come up directly before the US Supreme Court (Myren 1993), there is still uncertainty about whether total denial of marketable development rights on farmland could be ruled a taking. In the past, several scholars have expressed optimism that restrictions on development would not likely be regarded as a ‘taking’ so long as some economically viable use is left. However, the 1992 US Supreme Court decision regarding ‘Lucas’ (1992) may have made the situation somewhat more uncertain; see Mandelker 1993, Lazarus 1992. The court applies a severe per se rule to any situation where no ‘economically viable use’ whatsoever is left, but leaves the law vague regarding situations of near total takings. So long as agriculture is economically lucrative, past optimism has no reason to recede. But it might prove to be less secure if farming economics were to render the ‘beneficial use’ assumption tenuous, especially since farmland preservation often involves additional strata of regulations regarding runoff water, soil erosion, fertilizers, etc.

5. The Relationships Between Methods And Degrees Of Success

Achieving effective preservation is apparently much more complex and elusive than simply selecting from among the set of tools outlined above. Research shows that there is little direct relationship between the degree of success in preservation and the ostensible stringency of the tool applied (the research findings are presented in Alterman 1997). The two greatest success stories in farmland preservation among the countries studied—The Netherlands and Britain—do not primarily rely on direct control of farmland conversion. Furthermore, success in preservation does not depend on the characteristics of the broader planning system. The UK and The Netherlands have planning systems that, within the European vintage, are very different from each other (for a comparative analysis of national land-use planning in 10 advanced economy countries, including those analyzed in this research paper, see Alterman 2001), yet both are very successful. Nor is success intimately tied with the question of whether compensation for ‘taking’ is due. Most of the countries surveyed—indeed, all but possibly the USA—do not grant landowners compensation rights for denial of development permission on farmland, yet they exhibit widely varying degrees of success in preservation. In the USA there are significant variations between states in degrees of success in preservation, even though takings law in its constitutional aspects, is basically similar.

What, then, are the secrets of success in farmland preservation? First, the laudable achievements of the UK and The Netherlands could not have come about had the doctrine in these countries continued to focus on the preservation of agricultural land per se. In both The Netherlands and the UK, the concept of farmland preservation today draws much less attention than in the USA and Canada, despite the former countries’ higher population densities and smaller area of farmland per capita. Rather, in the UK and The Netherlands (and belatedly in Israel) there has been an overt redefinition of farmland preservation as countryside preservation. Second, both countries have achieved this outcome through national level policies that are planning driven, shared and applied effectively by local and regional planning authorities, and are less reactive to incremental developer initiatives than in the USA. Third, the UK and The Netherlands focus on the containment of growth of urban areas through infill and higher densities, many times higher than those prevalent in most US cities and suburbs, even where ‘smart growth’ is adopted. Fourth, and perhaps most crucially, in both countries, preservation policies enjoy wide public support among electoral constituencies. Finally, planning policies in both countries are intolerant of sporadic exurban initiatives. They centrally determine the number and size of local governments, and notions such as ‘bottom up’ annexation initiatives are unthinkable. By contrast, since the 1980s, France, though relatively successful in the use of higher densities, is slack on local government management capacity and on national and regional planning. Now that the old tenure related preservation mechanisms are becoming economically obsolete, France is likely to achieve only lukewarm success in preservation.

Our most distinctive success story, The Netherlands, demonstrates that reliance on agricultural land conservation can no longer assure countryside conservation. The two are separate goals: economics may at times unite them, but will increasingly dissociate them, and may even place them at direct odds with each other by making industrialized farming in buildings lucrative. Countryside preservation must be considered in its own right.

Bibliography:

- Alterman R 1997 The challenge of farmland preservation: Lessons from a six-nation comparison. Journal of the American Planning Association 63(2): 220–43

- Alterman R 2001 National-level planning in democratic countries: A comparative perspective. In: Alterman R (ed.) National-Le el Planning in Democratic Countries: An International Comparison of City and Regional Policy-making. Liverpool University Press, Liverpool, UK, pp. 1–42

- American Farmland Trust 1997 Saving American Farmland: What Works. American Farmland Trust Publication

- Bruce M 1998 Thirty years of farmland preservation in North America: Discourses and ideologies of a movement. Journal of Rural Studies 14(2): 233–47

- Burchell R W, Listokin D, Galley C C 2000 Smart growth: More than a ghost of urban policy past, less than a bold new horizon. Housing Policy Debate 11(4): 821–79

- Callies D L 1994 Preserving Paradise: Why Regulation Won’t Work. University of Hawaii Press, Hawaii

- Coughlin R E 1991 Formulating and evaluating agricultural zoning programs. Journal of the American Planning Association 57(2 Spring): 183–92

- Daniels T L 1998 When City and Country Collide: Managing Growth in the Metropolitan Fringe. Island Press

- DeGrove J M, Miness D A 1992 The New Frontier for Land Policy: Planning and Growth Management in the States. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, MA

- Endicott E (ed.) 1993 Land Conservation through Public Private Partnerships. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, MA

- Elson M J, Walker S, Macdonald R 1993 The Effectiveness of Greenbelts. The Stationery Office Books, HMSO, London

- Ferguson C A, Akram K 1992 Protecting farm land near cities: Trade-offs with affordable housing in Hawaii. Land Use Policy (Oct): 259–71

- Gale D E 1999 Land use planning, environmental protection and growth management: The Florida experience. Journal of the American Planning Association 65(3): 344–5

- Howe D A 1993 Growth management in Oregon. In: Stein J M (ed.) Growth Management: The Planning Challenge of the 1990s. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 61–75

- Kayden 2001 National land use planning and regulation in America: Something whose time has never come. In: Alterman R (ed.) National-Level Planning in Democratic Countries: An International Comparison of City and Regional Policymaking. Liverpool University Press, Liverpool, UK, pp. 44–65

- Kushner J A 2000 Smart growth: Urban growth management and land-use regulation law in America. Urban Lawyer 32(2): 211–38

- Lowry R W 1998 Preserving Public Lands for the Future: The Politics of Intergenerational Goods. Georgetown University Press, Washington

- Mandelker D R, Payne J M 2001 Planning and Control of Land Development: Cases and Materials, 5th edn. Mathew Bender and Co

- Myren R S 1993 Growth control as a taking. The Urban Lawyer 25(2, Spring): 385–405

- Nelson A C 1992 Preserving prime farmland in the face of urbanization: Lessons from Oregon. Journal of the American Planning Association 58(4, Autumn): 467–88

- Pothukuchi K, Kaufman J L 2000 The food system: A stranger to the planning field. Journal of the American Planning Association 66(2), Spring: 34–45

- Pruetz R 1997 Saved by Development. Arje Press, Burbank, California

- Reid E P, Yeates M 1991 Bill 90—An act to protect agricultural land: An assessment of its success in Laprairie County, Quebec. Urban Geography July-August: 295–309

- Sax L J 1994 Property Rights and The Economy of Nature: Understanding Lucas . South Carolina Coastal Council. Land Use and Environment

- Stein J M (ed.) 1993 Growth Management: The Planning Challenge of the 1990s. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA

- US Department of Agriculture and the Council on Environmental Quality 1981 National Agricultural Land Study

- Ward R M 1991 The US farmland protection policy act: Another case of benign neglect. Land Use Policy Jan: 63–8