Sample Ecology and Organizations Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of environmental research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Inspired by the question, Why are there so many kinds of organizations? (Hannan and Freeman 1977), organizational ecology aims to explain how sociopolitical and economic conditions affect the relative abundance and diversity of organizations and to account for their changing composition over time. Ecological research typically begins with three observations: (a) diversity is a property of aggregates of organizations, (b) organizations’ members often have difficulty devising and executing organizational changes fast enough to meet the demands of uncertain and changing environments, and (c) the community of organizations is unstable—organizations arise and disappear continually.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Consequently, contrasting adaptation approaches, which emphasize individual organizations’ leaders cumulative strategic choices, ecological analyses formulate organizational change and variability at the population level, highlighting the creation of new and the demise of old organizations and populations.

Organizations, populations, and communities constitute the basic elements of ecological analysis. A set of organizations engaged in similar activities and with similar patterns of resource use constitutes a population. Organizational populations form as isolating processes, including technological incompatibilities, institutional actions such as government regulations, and environmental imprinting segregating one set of organizations from another. Populations develop relationships with other populations engaged in different activities that bind them into communities. Organizational communities are functionally integrated systems of interacting populations in which the outcomes for organizations in any one population are intertwined fundamentally with those in other interrelated populations. In broad terms, ecological theory and research focus on three themes: demographic processes, ecological processes, and environmental processes.

1. Demographic Processes

1.1 Age and Size Dependence

The relationship between organizational aging and failure is a central line of demographic inquiry. Until recently, the predominant view was the liability of newness (Stinchcombe 1965), which assumes that because they have to learn new social roles, create new organizational routines, and lack endorsements and exchange relationships, young organizations will have higher failure rates. A complementary viewpoint is that selection processes favor structurally inert organizations capable of demonstrating reliability and accountability, which requires high reproducibility. Since reproducibility, achieved through institutionalization and routinization, increases with age, older organizations should be less likely to fail (Hannan and Freeman 1984).

A related line of research examines how organizational size influences failure. Small organizations’ propensity to fail results from several liabilities of smallness, including problems with recruiting and training employees, raising capital, and handling costs of regulatory compliance. Moreover, as organizations grow, increasingly they emphasize predictability, formalization, and control, increasing their reliability and accountability, and lowering their vulnerability to failure. The significance of ‘smallness’ stems in part from its relation to ‘newness’: since new organizations tend to be small, if small organizations have higher failure rates, empirical evidence of a liability of newness may actually reflect specification error. Although early studies consistently found a liability of newness, later studies controlling for time-varying size often do not, which has prompted formulation of alternative views on age dependence.

The liability of adolescence (Fichman and Levinthal 1991) predicts a -shaped relationship between age and failure. New organizations begin with a stock of assets (e.g., goodwill, psychological commitment, financial resources) that buffers them during an initial ‘honeymoon’ period—even if early outcomes are unfavorable. The larger the initial stock, the longer the buffer. As initial endowments are depleted, however, organizations unable to meet ongoing resource needs because, for example, they are unable to establish effective routines or exchange relations, may fail.

Liabilities of newness and adolescence yield divergent accounts of age dependence for young organizations, but because processes underlying these models occur early in organizational lifetimes, they do not apply to older organizations. The liability of aging (Barron et al. 1994) identifies processes affecting older organizations and predicts that failure increases with aging. The liability of aging begins with another insight from Stinchcombe’s (1965) essay: organizations are imprinted by their founding environment. As environments change, however, bounded rationality and structural inertia make it difficult for individuals to keep their organizations aligned with environmental demands. Encountering a series of environmental changes may thus expose aging organizations to a risk of obsolescence. Aging may also bring about senescence: an accumulation of internal politics and precedent that impede action. Obsolescence and senescence pose separate risks. Senescence is a direct effect of aging; obsolescence a result of environmental change.

Among studies controlling for time-varying size, empirical estimates are mixed (Baum 1996). The divergent age dependence results might reflect nonproportionality (e.g., effect of age varies with size) masking ‘true’ age effects or alternatively variation in age dependence across populations. To resolve such questions, research must test alternative models’ mediating variables directly rather than using age as a surrogate for all underlying constructs. Such an approach treats the alternatives as complementary rather than (falsely) as competing models.

1.2 Organizational Change

Most research on organizational change concentrates on content: a change to a more (less) advantageous configuration is considered adaptive (detrimental). Complementing this focus, structural inertia theory (Hannan and Freeman 1984) emphasizes the change process and raises two questions.

1.2.1 How Changeable Are Organizations? The structure in structural inertia theory refers only to core organizational features (goals, authority structures, core technology, and market strategy) related to mobilizing scarce resources for beginning an organization and the strategies used to maintain resource flows (Hannan and Freeman 1984). Peripheral features buffer an organization’s core from uncertainty. Core features exhibit greater inertia than peripheral features, but the claim is not that they never change, only that ‘the speed of reorganization is much lower than the rate at which environmental conditions change.’ Nor does structural inertia theory remove individuals from responsibility or control over their organization’s survival. Indeed, the challenge of overcoming structural inertia implies that the capacity of individuals to change organizations successfully is of great importance. Inertia also varies with age and size. Because older organizations have more formalized structures, standardized routines, institutionalized power structures, and dependencies, inertia should increase with age. Moreover, as organizations grow, they increasingly emphasize predictability, formalization, and control, becoming more inflexible. Large size, by buffering organizations from environmental demands, may also reduce the impetus for change.

Although not included in structural inertia theory, a complete understanding of change processes requires consideration of organizations’ change histories (Amburgey et al. 1993). The more experienced an organization becomes with a particular change, the more likely it is to repeat it. If the change becomes causally linked with success in decision-makers’ minds—rightly or wrongly—repetition is even more likely. The change process may thus itself become routinized, creating organizational momentum—the tendency to maintain direction and emphasis of prior actions in current behavior. To reconcile momentum with commonly observed periods of organizational inactivity, Amburgey et al. propose that local search processes (Cyert and March 1963) reinforce momentum immediately after a change occurs, but it subsequently declines.

Empirical studies yield mixed support for structural inertia theory; support for momentum appears stronger (Baum 1996). Overall, research indicates that, while inertia and momentum constrain them, organizations often initiate change in response to environmental shifts. Of course, inertia and momentum are not necessarily harmful: in addition to promoting performance reliability and accountability, in an uncertain environment they can keep organizations from responding too quickly and frequently to environmental change. Ultimately, whether inertia and momentum are adaptive depends on the hazardousness of change.

1.2.2 Is Change Beneficial? According to structural inertia theory, core change destroys or renders obsolete established routines, disrupts exchange relations, and undermines organizational legitimacy by impairing performance reliability and accountability. Thus, organizations may often fail precisely as a result of their attempts to survive—even attempts that might, ultimately, have proved beneficial. Because their structures, routines, and relationships are more institutionalized, older organizations are especially likely to experience disruption following core change. In contrast, large organizations can buffer themselves from disruption by, for example, maintaining both old and new routines during transition or overcoming deprivations and competitive challenges accompanying the change. If an organization survives the short-run hazard, its failure rate is predicted to decline as performance reliability, exchange relations, and legitimacy are re-established over time. Only if the rate of decline is faster than before the change, however, will the organization ultimately benefit from taking the short-term risk.

Empirical studies indicate that while core change is not necessarily disruptive in the short run, organizations do not necessarily improve their survival chances in the long run either (Baum 1996). Two research design problems, however, appear likely to produce systematic underestimates of the hazardousness of change. First, the annual data typically used may not detect the deadliest core changes—those proving fatal within a year. Second, because organizations founded before a study period are not observed when they are youngest, smallest, and most likely to be subject to vulnerable change, their inclusion likely biases downward the risk of change.

2. Ecological Processes

2.1 Niche-Width Dynamics

Niche-width theory (Hannan and Freeman 1977) focuses on two aspects of environmental variability to explain the differential survival of specialists, which possess few slack resources and concentrate on a narrow range of customers, and generalists, which attempt to appeal to the mass market and exhibit tolerance for more varied environments. Variability refers to the variance in environmental fluctuations about their mean over time. Grain refers to the patchiness of these variations with fine-grained variations frequent and coarse-grained infrequent. The key prediction is that in fine-grained environments, with large magnitude variations, specialists out-compete generalists regardless of environmental uncertainty. Specialists ride out the fluctuations; generalists are unable to respond quickly enough to operate efficiently. Thus, niche-width theory challenges the classic prediction that uncertain environments always favor generalists that spread their risk.

In contrast to niche-width theory, which implies an optimal strategy for each population, Carroll (1985) proposes that, in environments characterized by economies of scale, competition among generalists to occupy the center of the market frees peripheral resources that are most likely to be used by specialists. He refers to the process generating this outcome as resource partitioning. His model predicts that in concentrated markets specialists can exploit more resources without engaging in direct competition with generalists, and so that while increasing market concentration increases the failure of generalists, it lowers the failure of specialists.

Although the specialist–generalist distinction is now common in ecological research, tests of niche-width and resource-partitioning theories’ predictions are limited, and no studies explicitly contrast niche-width and resource-partitioning predictions. Recent studies frequently examine spatial and temporal environmental variation without reference to niche width, pointing to the need to elaborate niche-width models to encompass spatial as well as temporal environmental variation.

2.2 Population Dynamics And Density Dependence

Research on founding and failure in organizational ecology has paid considerable attention to endogenous population dynamics and density dependence. Prior population dynamics—patterns of founding and failure—shape current founding rates (Delacroix and Carroll 1983). Initially, prior foundings signal opportunity to entrepreneurs, encouraging founding. But as foundings increase, resource competition increases, discouraging founding. Prior failures have analogous effects. At first, failures release resources available to entrepreneurs. But further failures signal a hostile environment, discouraging founding. Resources freed by prior failures may also enhance the viability of established organizations, lowering failures (Carroll and Delacroix 1982). Density-dependent explanations for founding and failure are similar though not identical. Initial increases in the number of organizations can increase the legitimacy of a population, enhancing the capacity of its members to acquire resources. However, as a population continues to grow, competition with others for scarce common resources intensifies. Combined, the mutualistic and competitive effects imply a -shaped relationship between density and founding and a -shaped relationship between density and failure (Hannan and Carroll1992).

Studies of a wide variety of organizational populations provide empirical support for density-dependent founding and failure. By comparison, population dynamics findings are mixed and, when modeled together with population density, population dynamics effects are weaker and less robust. One explanation for the dominance of density dependence over population dynamics is the systematic character of density relative to the changes in density produced by founding and failure. A related explanation is the sensitivity of rate dependence estimates to outliers. These issues need to be examined more thoroughly before population dynamics is abandoned, which has been the trend in recent research.

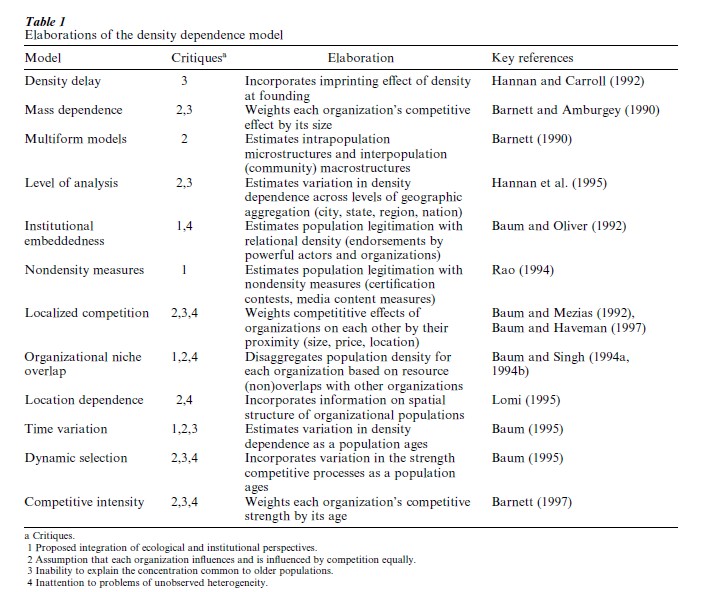

Although support for density dependence is strong, it has received critical attention for its (a) proposed integration of ecological and institutional perspectives, (b) assumption that each organization influences and is influenced by competition equally, (c) inability to explain the concentration common to older populations, and (d) inattention to problems of unobserved heterogeneity. Several innovative elaborations, respecifications, and measures have been advanced recently to address questions raised by the initial formulation (summarized in Table 1). Although Hannan and Carroll (e.g., 1992, 1995) frequently rebuke such efforts, they nevertheless promise to improve substantive interpretation and realism of the original model.

3. Environmental Processes

Environmental processes are central to organizational ecology, shaping appropriate organizational forms and conditioning historical–structural relationships (e.g., the basis of competition).

3.1 Institutional Processes

Organizational environments are more than simply sources for inputs, information, and knowhow for outputs. Institutionalized rules and beliefs about organizations also figure prominently (DiMaggio and Powell 1983, Meyer and Rowan 1977). Institutional theory emphasizes that organizations must conform to these rules and requirements if they are to receive support and be perceived as legitimate. Density dependence theory views the relationship between ecological and institutional theory as complementary and synthesizes them within a single explanatory framework. However, institutional theory is increasingly conceived as contextual to ecological theory—the relationship between them is not only complementary, it is also hierarchical (Baum 1996).

From this point of view, the institutional environment constitutes the broader social context for ecological processes—the institutional environment may prescribe the criteria for judging whether an organization or entire population is worthy of continued survival. Ecological research on institutional processes typically compares rates of founding, failure, change, or growth across organizational populations or time as the institutional arena of a particular population changes in terms of its political turbulence, government regulation, or institutional embeddedness (Baum 1996). Most past research has treated institutional change as exogenous. Studying how ecological dynamics of organizations shape institutional change can, however, enrich our understanding of institutional change and persistence.

3.2 Technological Processes

Technological innovation influences organizational populations profoundly by disrupting markets, changing the relative importance of resources, challenging organizational learning capabilities, and altering the basis of competition. Supporting Schumpeter’s characterization of technological innovation as a process of creative destruction, research supports the idea that technologies evolve over time through cycles of long periods of incremental change, which enhance and institutionalize an existing technology, punctuated by technological discontinuities in which new, radically superior technologies displace old, inferior ones, making possible order-of-magnitude or more improvements in organizational performance (Tushman and Anderson 1986).

The new technology can either be competenceenhancing, building on existing knowhow and reinforcing incumbents’ positions, or competence-destroying, rendering existing knowhow obsolete and making it possible for newcomers to become technologically superior competitors. The technological ferment spawned by the discontinuity ends with the emergence of a dominant design, a single architecture that establishes dominance in a product class (Anderson and Tushman 1990), and technological advance returns to incremental improvements on the dominant technology. Although the universality of this technology cycle is debated, it has proved illuminating in a wide variety of industries.

Technological innovation creates opportunities for entrepreneurs to found new organizations and establish competitive positions as incumbents’ sources of advantage decay. Technological innovation also creates uncertainty and risk for incumbents because its outcomes can be only imperfectly anticipated. An innovation’s impact may not be known until it is too late for incumbents using older knowhow to compete successfully with new competitors; gambling too early on a given innovation may jeopardize an incumbent’s survival if that technology turns out not to become dominant. Thus, underlying technologies and technological innovation may influence organizational populations’ competitive dynamics and evolution profoundly. Ecological research relating technology cycles to population dynamics, although limited in scope, yields compelling support for this assertion (Baum 1996). Although past research typically treats technological change as exogenous, studying how ecological processes shape technological change can deepen our understanding of technology cycles by examining the dynamics of organizational support for new technologies.

Bibliography:

- Amburgey T L, Kelly D, Barnett W P 1993 Resetting the clock: The dynamics of organizational change and failure. Administrative Science Quarterly 38: 51–73

- Anderson P, Tushman M L 1990 Technological discontinuities and dominant designs: A cyclical model of technological change. Administrative Science Quarterly 35: 604–33

- Barnett W P 1990 The organizational ecology of a technological system. Administrative Science Quarterly 35: 31–60

- Barnett W P 1997 The dynamics of competitive intensity. Administrative Science Quarterly 42: 128–60

- Barnett W P, Amburgey T L 1990 Do larger organizations generate stronger competition. In: Singh J V (ed.) Organizational Evolution: New Directions. Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 78–102

- Barron D N, West E, Hannan M T 1994 A time to grow and a time to die: Growth and mortality of credit unions in New York City, 1914–1990. American Journal of Sociology 100: 381–421

- Baum J A C 1995 The changing basis of competition in organizational populations: Evidence from the Manhattan hotel industry, 1898–1990. Social Forces 74: 177–205

- Baum J A C 1996 Organizational ecology. In: Clegg S, Hardy C, Nord W (eds.) Handbook of Organization Studies. Sage, London, pp. 77–114

- Baum J A C, Haveman H A 1997 Love thy neighbor? Differentiation and agglomeration in the Manhattan hotel industry. Administrative Science Quarterly 42: 304–38

- Baum J A C, Mezias S J 1992 Localized competition and/organizational failure in the Manhattan hotel industry, 1898–1990. Administrative Science Quarterly 37: 580–604

- Baum J A C, Oliver C 1992 Institutional embeddedness and the dynamics of organizational populations. American Sociological Review 57: 540–59

- Baum J A C, Singh J V 1994a Organizational niche overlap and the dynamics of organizational mortality. American Journal of Sociology 100: 346–80

- Baum J A C, Singh J V 1994b Organizational niche overlap and the dynamics of organizational founding. Organization Science 5: 483–501

- Carroll G R 1985 Concentration and specialization: Dynamics of niche width in populations of organizations. American Journal of Sociology 90: 1262–83

- Carroll G R, Delacroix J 1982 Organizational mortality in the newspaper industries of Argentina and Ireland: An ecological approach. Administrative Science Quarterly 27: 169–98

- Cyert R M, March J G 1963 A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

- Delacroix J, Carroll G R 1983 Organizational foundings: An ecological study of the newspaper industries of Argentina and Ireland. Administrative Science Quarterly 28: 274–91

- DiMaggio P J, Powell W W 1983 The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review 48: 147–60

- Fichman M, Levinthal D A 1991 Honeymoons and the liability of adolescence: A new perspective on duration dependence in social and/organizational relationships. Academy of Management Review 16: 442–68

- Hannan M T, Carroll G R 1992 Dynamics of Organizational Populations: Density, Competition, and Legitimation. Oxford University Press, New York

- Hannan M T, Carroll G R 1995 Theory building and cheap talk about legitimation: Reply to Baum and Powell. American Sociological Review 60: 539–44

- Hannan M T, Carroll G R, Dundon E A, Torres J C 1995 Organizational evolution in a multinational context: Entries of automobile manufacturers in Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, and Italy. American Sociological Review 60: 509–28

- Hannan M T, Freeman J 1977 The population ecology of organizations. American Journal of Sociology 83: 929–84

- Hannan M T, Freeman J 1984 Structural inertia and/organizational change. American Sociological Review 49: 149–64

- Lomi A 1995 The population ecology of organizational founding: Location dependence and unobserved heterogeneity. Administrative Science Quarterly 40: 111–44

- Meyer J W, Rowan B 1977 Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology 83: 340–63

- Rao H 1994 The social construction of reputation: Certification contests, legitimation and the survival of organizations in the American automobile industry; 1895–1912. Strategic Management Journal 15 (Winter Special Issue): 29–44

- Stinchcombe A L 1965 Social structure and/organizations. In: March J G (ed.) Handbook of Organizations. Rand McNally, Chicago, pp. 153–93

- Tushman M L, Anderson P 1986 Technological discontinuities and/organizational environments. Administrative Science Quarterly 31: 439–65