Sample Cultural Ecology Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of environmental research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

The central interest of cultural ecology is the mutual relations of people and the environment (of places and resources) they occupy and use. Julian Steward coined the term in 1937, to distinguish it from biological, human, and social concepts of ecology. Steward defined it as:

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

the study of the processes by which a society adapts to its environment. Its principal problem is to determine whether these adaptations institute internal social transformations or evolutionary change. It analyzes these adaptations, however, in conjunction with other processes of change. Its method requires examination of the interaction of societies with one another and with the natural environment (Steward 1968).

Cultural ecology, an inquiry dominated by geographers and anthropologists, has sought to make a place for environment in understanding and explaining the human condition (i.e., culture alone cannot explain culture or cultural change). It studies the significance of environment and the interactions humans have with it, with influences going in both directions: humankind’s role in modifying the earth, and the environment’s influences on human nature and culture. There is the undoubted fact that humans use the world around them and solve questions about how to make the material world meet human needs and wants. Adaptation of and to the material world is a great intellectual accomplishment of humankind.

Steward wrote the essay on cultural ecology for the 1968 edition of the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. This research paper, after summarizing the main purposes and methods of cultural ecology in the early 1960s, traces the development of the field through the subsequent four decades. The purpose of this research paper is to illustrate the kinds of questions asked in cultural ecology and the way they are answered. Examples have been chosen for their illustrative power.

1. Major Themes In Cultural Ecology

The most important preoccupation in cultural ecologic research, particularly when done by anthropologists, has been with cultural adaptation. According to Steward, one studied (a) the connections between an environment and the technology people use to exploit it, (b) the patterns of behavior that result when particular technologies are used, and (c) the effects, if any, these have on other cultural patterns (Steward 1955). The resulting changes set in motion by cultural adjustments to environmental conditions constituted, in Steward’s phrase, a process of multilinear cultural evolution (the idea being that there are significant, but not universal, regularities in cultural evolution, that lead to parallel form, function, and sequence in quite disparate, unrelated cultures). Although complex, this approach is essentially a functionalist one, which argues that there are predictable relations between a given set of environment technology relations and the evolution of other aspects of culture–social institutions and individual personality and behavior.

This theme of adaptive dynamics has been further developed by Gregory Knapp in Andean Ecology (1991). An associated theme, studied by Fredric Barth (1956), was economic specialization by different groups, with mutually beneficial reciprocal relationships. The resulting regions of specialization he termed econiches.

Works cited in this research paper which do not, because of space limitations, appear in the Bibliography:, can be found in one, or more, of the following four review essays in cultural ecology: Bassett and Zimmerer 2001, Butzer 1989, Grossman 1977, and Porter 1978. For reviews of cultural ecology by anthropologists, see Hardesty 1979, Moran 1990, Netting 1977, and Vayda and McCay 1975.

The second most important theme in cultural ecology can be called agricultural stability and change, an intersecting set of topics including population pressure and agricultural intensification (Boserup 1965, Netting 1968); carrying capacity (Allan 1949, Carniero 1956, Sahlins 1958); agricultural involution (Geertz 1963); environmental cognition and systems of indigenous knowledge (Porter 1965); systems analysis (Von Bertalanffy 1959); and energetics (Rappaport 1968). Two perspectives, synchronic, which focuses on contemporary conditions, and diachronic, which has a deep cultural historical, even archeological, basis, have been evident in much cultural ecological study (Butzer 1964, 1989, Denevan 1966). Agroecology, the study of field systems, crop management through habitat modification, and fertility management, has been a major interest of cultural ecologists, a good part of which has been archeological in nature—relict fields, terraces, irrigation systems, etc. (Denevan 1972, Doolittle 1988, Turner 1983, Dunning and Beach 1994).

Other themes and concepts that figured in cultural ecology by the mid-1960s include environmental risks and hazards (White 1961, Kates 1962); the behavioral environment (Kirk 1963) and environmental perception (Saarinen 1966); and medical ecology (May 1958, Hunter 1974, and reviewed by Pyle 1976, and Earickson et al. 1989).

2. Methods

The methods of the cultural ecologist are essentially those of the ethnographer—careful observation and recording of the ideas and material practices of the people whose culture is being studied, as well as participant observation and recording of life histories. The difference lies, perhaps, in the emphasis placed on the biophysical world the people use. Whereas the ethnographer pays great attention to kinship, law, language, origin myths, and religious beliefs and practices, the cultural ecologist devotes comparable attention to knowledge and beliefs regarding plants, soils, seasons, terrain, agriculture, livestock, and other aspects of the environment the people use. Another difference may lie in the degree to which cultural ecologists collect and carefully measure highly detailed data relating to resource use and the environment, and seek to understand the meaning of complex interrelationships among the data. An example is Eric Waddell’s work in The Mound Builders (1972), in which relationships of sweet potato varieties, mound size, cold air drainage, size of soil aggregates after tillage, elevation of gardens, and frost hazards are considered.

Among cultural ecology’s methods is an anthropological ethnographic use of an approach associated with the linguist Pike (1966); namely, a focus on the internal, emic world of contextualized meanings of terms, in contrast to any universal, etic, or standardized manner of uttering a term (derived from phonemic vs. phonetic). The cultural ecologist also uses western science to the extent possible and when appropriate to the task at hand, whether it be carbon- 14 dating methods, measurement of energy-water budget variables, or analysis of satellite imagery. The use of western science methods was strongly endorsed in the 1970s by such cultural ecologists as Karl Butzer (1982) and Harold Brookfield (1968). One further precept is that the cultural ecologist should be historical to the extent possible. A sensitivity to historical aspects and change through time helps ensure that analysis avoids freezing cultural groups into an ahistorical ethnographic present, an approach that permits them ethnography but denies them history.

Cultural ecology’s use of the emic approach as a method and research framework frequently emerges through a common sense evaluation of how to do field work, and has been independently invented by field researchers any number of times. For example, the soils of the Pokot of western Kenya can be described using Western science—the US Soil Conservation Service’s Comprehensive Classification System, but it would have no meaning for Pokot farmers, who have their own well-developed system of soil names with associated characteristics, typical locations, and uses. Since Pokot behavior is informed by their names for and understanding of soils, one learns much by using their classification (Porter and Sheppard 1998).

3. Scale And Location

The scale of cultural ecological studies reflects the intense nature of the research that produces it. Most cultural ecological study concerns small areas and small groups of people—a village, a community, a valley. By judicious use of synedoche and caveat, the cultural ecologist may claim that the findings for the smaller group represent the larger culture. Indeed, following Brookfield’s early lead (1962), cultural ecologists commonly work at multiple scales: the individual, the household, the community, the culture (and its territory) overall, as well as the culture in larger settings—national, international, and with reference to global political economy.

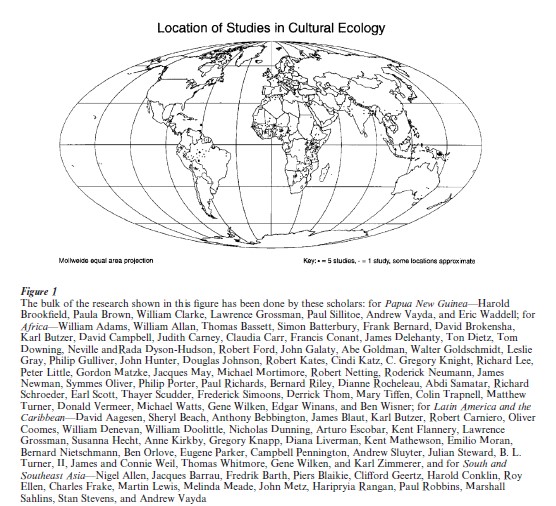

The ‘third world’ location of most cultural ecological research is illustrated in Fig. 1. It is based on a large Bibliography: on cultural ecology, collected over the years, plus searches, by title and subject, of several library databases (anthropology and geobase) using the linked key words cultural ecology. The search generated over 700 books and articles, either with the term cultural ecology in the title, or classified under the subject heading cultural ecology. The geographic locations of as many of these works as could be determined (over 550) were plotted on the map. The resulting pattern (an approximation) emphasizes the tropical and subtropical, colonial location of the bulk of the research. An exception is the work that has been done among native American Indian groups in the US and Canada. There are significant clusters in Papua New Guinea (where much early work originated), Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America (especially Mayan, Andean, and Amazonian), and Himalayan south Asia.

The cultures that have been studied by cultural ecologists have tended to be preliterate, agrarian, and part of the former colonized world. The goal of the cultural ecologist has been to understand and convey the life-world and life-ways of indigenous cultures. It has sought to give a voice to the knowledges, beliefs, and values of indigenous peoples. Cultural ecology, therefore, constitutes, in the language of contemporary social sciences, a discourse. Its effects have been muted, since other discourses in the social sciences and in policy arenas are dominant. This may be changing, however, as witness the World Bank’s recent focus on social capital and forms of reciprocity and community that tap local knowledge.

4. Cultural Ecology 1960–2000

Much happened in cultural ecological research in the final four decades of the twentieth century. The remaining discussion is divided into three sections: the evolution of cultural systems, the study of livelihood and environment, and recent critiques of cultural ecology.

4.1 The Evolution Of Cultural Systems

People appraise the potentialities and constraints of their surroundings in different ways: (a) in the way they organize space (settlement patterns, field dispersal, use of different ecological zones), (b) in their use of local resources (irrigation, crop varieties, medicinal plants), (c) in the organization of internal relations (family, clan, age-set, bridewealth, neighbors, ritual and ceremony), and (d) in the way they connect with larger social and economic forces—local and national governments and the global economy (labor migrancy, remittances, production and sale of cash crops, contract farming, adoption of new technologies). Changes in circumstances in any of these domains can affect any of the other domains and occasion cultural change.

As an illustration of efforts to demonstrate how cultures evolve in response to changes in environmental technological circumstances, consider the work of Walter Goldschmidt and co-workers in the Culture and Ecology in East Africa Project (1965). The central hypothesis of this project was that a major change in livelihood (say from livestock keeping to farming) would require changes in the nature and inter-relationships of social institutions and people, and at a deeper level, changes in the attitudes and personality characteristics of individuals. With a change in livelihood, social institutions and the repertoire of techniques must be refashioned or abandoned and replaced by new ones to meet changed circumstances.

The project centered on pastoralism, with farming used as its foil. Four cultural groups in east Africa (Sebei, Pokot, Wakamba, and Wahehe) were chosen because in each there was a group whose members were predominantly pastoralists and another whose members were predominantly farmers. It was hypothesized that the Sebei, for example, were ‘originally’ pastoralists, but over a period of generations, after some of their members took up farming on the higher potential parts of Mount Elgon in Uganda, growing bananas, maize, and coffee as a cash crop, their social institutions adapted to the requisites of horticulture. In the process they transformed a lightly peopled montane forest environment into one of dense human settlement.

First, the reader should envisage the dramatic contrast in settlement pattern between the farming and pastoral communities Goldschmidt studied. In the farming area the population density was 343 people sq. km (888 people/sq. mile), a landscape of nearly continuous banana groves, which shaded coffee trees. Among the pastoralists, who grew some maize and finger millet, the population density was seven people sq. km (19 people/sq. mile), with large open tracts of unpeopled grazing land, a sparse Acacia savanna.

Goldschmidt, in Culture and Behavior of the Sebei (1976), documented numerous ways in which institutions that were important for pastoralists, changed under a regime of cultivation. For example: the pororyet, a military organization based on age grades and designed for offensive action and rapid movement in open country, became among the farmers a resident militia of a fixed territory and made up of men of all ages; the misisi, a ‘first fruits’ thanksgiving harvest ritual, based on a carefully defined list of kin, was transformed into the mukutanek (sharing), a ritual beer party to which one invited neighbors, not kin. Its purpose came to be maintenance of good relations with neighbors. The chomi ntarastit, an oathing ceremony originally used to settle interclan disputes among the pastoralists, became a ceremony in which adult male residents of the farming community swore to abide by laws intended to preserve peace and public order; the chichomnko lekok, a ceremony among pastoralists performed between half-brothers, when they were toddlers, to ensure that there would be peace between them, was used by adults among the farmers to resolve tension and disputes over land and inheritance; age grades and male and female circumcision ceremonies became less formal and in certain instances were abandoned altogether in the shift from pastoral to farming livelihoods; the tokapsoi and the toka che kichenkochi korket, terms that refer, respectively, to a man’s cattle and those that have been anointed and smeared for a wife, and over which she has control (but which pass to her sons upon her death), were applied to farmed fields.

Edgerton, in The Individual in Cultural Adaptation (1971), explored the inner worlds of beliefs, attitudes, and personality of the Sebei and members of the other three cultures. His purpose was to see how pastoralists and farmers differed. He interviewed samples of about 30 adult men and 30 adult women in the pastoral and farming communities of the four cultures, administering a rich variety of test instruments. Although there were greater within-culture similarities than between cultures (i.e., ‘culture’ explained more than ‘ecology’), there were 31 categories of difference between the people of the eight Culture and Ecology communities that were statistically significant. Some of these differences were attributable clearly to farming or herding. He discussed the various attributes along a continuum with herding at one pole and farming at the other. Five attributes were found close to the pastoral pole: affection, direct aggression, divination, independence, and self-control. Nearly as central in importance were adultery, sexuality, guilt-shame, depression, and respect for authority. In contrast, the attitude closest to the farming pole was disrespect for authority, but the following attributes were also characteristic of farmers: anxiety, conflict avoidance, emotional constraint, hatred, impulsive aggression, and indirect action. As one considers the requirements of a settled, sedentary life, and life in a community where one cannot easily escape the proximity of neighbors, in contrast to the demands of a life managing livestock, where one must be flexible in meeting the daily, unremitting needs of animals for water, graze, browse, salt, and safety, one can see ways in which the attributes emphasized in each lifeway make sense. In the broadest terms: ‘Farmers must create institutions for the preservation of peaceable relationships, … [P]astoralists must create ideals that bind together persons who need to preserve a sense of community in the face of the fact that they are forced by economic circumstances to operate as individualists’ (Edgerton 1971).

The foregoing illustration of Steward’s project to ‘study the processes by which society adapts [or maladapts] to its environment,’ could be expanded by the citation of many other scholars.

4.2 The Study Of Livelihood And Environment

The core of this theme is the nexus of population and resources, from which many subsidiary questions flow—limits to growth, the carrying capacity of the earth, agricultural intensification, soil erosion and environmental degradation, destruction of forest lands, with associated species extinctions and loss of biodiversity, problems of the global commons (oceans, atmosphere, lakes, forest habitat, and coastlines). Key events in the study of livelihood systems were: (a) Harold Brookfield’s 1964 article in Economic Geography, which argued the urgent need to include the interior dynamics of culture—that which lay in the beliefs, values, and attitudes of people, as well as their social institutions; (b) the appearance in 1965 of Ester Boserup’s The Conditions of Agricultural Growth (to which we return); (c) Roy Rappaport’s influential (1968) Pigs for the Ancestors, which illustrated systems theory, energetics, and homeostasis and feedback in ecological systems; (d) Robert Netting’s (1968) classic work on the Kofyar, as well as his influential monograph, Cultural Ecology (1977); (e) two studies of disruptions in subsistence systems brought about by commercial activities: Bernard Nietschmann (1973), on the Miskito Indians of Nicaragua, and Lawrence Grossman (1984), on the highlands of Papua New Guinea; and (f ) the publication of Piers Blaikie and Harold Brookfield’s Land Degradation and Society (1987). Blaikie and Brookfield emphasized the importance of using a nested set of scales for research, in order to show how decisions and policies at national and international levels affecting land ownership, commodity pricing, development assistance, etc., had impacts on people at local levels. They showed how poor farmers were marginalized, both literally and figuratively, and were unable in their struggle to eke out a living (and despite their better instincts) to avoid degrading the environments they were forced to use.

Boserup’s book challenged the classic argument of Thomas Malthus (that population can increase geometrically while agricultural productivity could only increase arithmetically). Her argument was that through slow sustained pressure of population on resources, people improved agricultural output. She focused on the means by which this was done: (a) the mobilization of labor, and (b) the tools appropriate to the vegetation managed by cultivators at the end of each fallow. She placed land on a continuum of use (forest fallow, bush fallow, short fallow, continuous cultivation) and examined a suite of expectations about the tools, the role of livestock, land ownership, and social and infractructural institutions and attitudes associated with different stages in land use intensification. Her work, supported by that of William Allan, whose The African Husbandman appeared the same year, transformed thinking in cultural ecology in many fruitful ways. Despite cogent critiques of her work, for neglecting capitalism, market relations, and the state, evidence of the impact and acceptance of her ideas is the now widespread use of the adjective Boserupian.

Environmental change induced by human action has also been an important theme in cultural ecology (Turner 1990). Some of it has speculated on population dynamics of past civilizations—Mayan, Incan, Egyptian (Denevan 1976, Butzer 1976). In contemporary terms it involves the inventorying of land use and land quality and subsequent tracking of changes in the geosphere and biosphere. These questions require a ‘big-science’ approach and involve the cooperation of different disciplines and international organizations. Among themes in this topic are land use change, climate change, pollution, and loss of plant diversity, farmland, and wilderness. Cultural ecologists contribute to some aspects of this inquiry.

4.3 Recent Critiques Of Cultural Ecology

Cultural ecology as practiced in an earlier period ran four interrelated risks: (a) that of assuming equilibrium and balance in the society studied, (b) ethnographic presentism, i.e., failing to give adequate attention to history and change in the society, (c) use of an agreeable, internal, circular functionalism in explanation, and (d) failure to incorporate influences external to the group being studied. Given these potential flaws, scholars sometimes found cultural ecology inadequate and incomplete as a research paradigm and modified or added to the approach (Porter 1978). Although one might argue for an earlier beginning of the radical critique of cultural ecology (Brookfield and Kirkby 1974), one seminal event was the publication of Michael Watts’ Silent Violence: Food, Famine and Peasantry in Northern Nigeria (1983). This book brought political economy, Marxian analysis of global capitalism, and the state more fully into the work of cultural ecologists. Watts in his writing and teaching has influenced a succeeding generation of cultural ecologists, many of whom prefer the term political ecology to describe their work. Political ecology has been a growth center of cultural ecology ever since, indeed, with efforts to go beyond political ecology to new, more effective approaches. An example is Liberation Ecologies edited by Peet and Watts (1996). The book argues for a single, all encompassing, poststructuralist, social science based on the discursive perspective and methods of critical theory as used in analysis in literature, the arts, and humanities. Both political ecology and cultural ecology are, they argue, inadequately theorized, and not sufficiently political. The various authors of Liberation Ecologies call for a reconceptualization of virtually everything: nature, environment, the state, class, gender, ethnicity, community, region, and identity. The central concern is with power relations and the contestations they generate at all scales, from the household (between wife and husband) to the state and the global economy. Liberation Ecologies, though full of stimulating ideas, does not, however, provide a unified alternative to political ecology, since its authors disagree on many questions.

Another critique of cultural ecology has been made by Karl Zimmerer (1994) in an article titled ‘Human geography and the ‘‘new ecology’’: the prospect and promise of integration,’ which proposes adoption of uncertainty principles and chaos theory in cultural ecological analysis, abandoning the underlying assumptions of homeostasis and ecological balance that characterized earlier work.

Among significant themes that have been developed are feminist political ecology (Carney 1993, Rocheleau et al. 1996, Schroeder 1999); the political ecology of protected areas (Neumann 1998, Stevens 1999, Nietschmann 1997); the political ecology of social movements (Bebbington 1996, Rangan 1996); and the theme of sustainability and global change (Chambers 1997, Turner 1990).

Although it has been critical of cultural ecology, political ecology should not be seen as an offshoot of cultural ecology. It is, rather, an enlarging of cultural ecology’s domain of inquiry and the conscious in-corporation of effects originating outside the ecological setting. Much early cultural ecological work was microscale and tended to study ensembles of things occurring at a place (site characteristics) as well as situational characteristics within the study area. Political ecology extended the scale of inquiry to include the global economy, intrusions of the state, markets, and other external influences.

Not all cultural ecologists accept the reconfiguration of cultural ecology as political ecology, and feel that with the addition of Marxian analysis and postmodern concerns over relations of power, knowledge, and resources, there has been a corresponding narrowing of inquiry and loss of the healthy eclecticism that has characterized cultural ecology, as well as moving it away from cooperation with the more positivist environmental sciences—ecology, paleoecology, and global change science (Turner 1997).

Cultural ecology remains a lively field of inquiry, asking questions that will not go away, and that can never be answered in fully satisfactory ways. Current approaches in cultural ecology, and its vigorous descendant, political ecology, reflect transformations in the social sciences themselves. At the same time there appears to be a diminution of the importance attached to the biophysical world and a western science under- standing of it. In these postmodern times, when ‘everything is socially constructed,’ cultural ecology can be expected to continue to reflect changing modes of thought in the wider society.

Bibliography:

- Bassett T J, Zimmerer K S 2001 Cultural ecology. In: Gaile G L, Willmott C J (eds.) Geography in America at the Dawn of the 21st Century. Oxford University Press, New York

- Blaikie P M, Brookfield H C 1987 Land Degradation and Society. Methuen, London

- Brookfield H C, Kirkby A 1974 On Man Environment and Change. International Geographical Union, Working Group on Man-Environment Theory. Work Notes No.1

- Butzer K W 1989 Cultural ecology. In: Gaile G L, Willmott C J (eds.) Geography in America. Merrill, Columbus, OH

- Chambers R 1997 Whose Reality Counts? Putting the First Last. Intermediate Technology Publications, London

- Edgerton R B 1971 The Individual in Cultural Adaptation. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Goldschmidt W R 1976 Culture and Behavior of the Sebei. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Grossman L S 1977 Man-environment relationships in anthropology and geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 67: 126–44

- Hardesty D L 1979 Ecological Anthropology. Wiley, New York

- Moran E J (ed.) 1990 The Ecosystem Approach in Anthropology. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI

- Netting R McC 1977 Cultural Ecology. Cummings Publishing Company, Menlo Park, CA

- Peet R, Watts M (eds.) 1996 Liberation Ecologies: Environment, Development, Social Movements. Routledge, London

- Pike K L 1966 Etic and emic standpoints for the description of behavior. In: Smith A G (ed.) Communication and Culture. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York

- Porter P W 1978 Geography as human ecology: A decade of progress in a quarter century. American Behavioral Science 22: 15–39

- Porter P W, Sheppard E S 1998 A World of Difference: Society, Nature, Development. Guilford Press, New York

- Steward J H 1955 Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, IL

- Steward J H 1968 Cultural ecology. In: Sills D L (ed.) International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Macmillan, New York, Vol. 4. pp. 337–44

- Vayda A P, McCay B J 1975 New directions in ecology and ecological anthropology. Annual Review of Anthropology 4: 293–306