Sample Environment And Common Property Institutions Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, chech our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The twentieth century witnessed many efforts to increase the sustainability of natural resource systems through reforms of property-rights systems. Many of these reforms have not achieved their intended outcomes. Instead, some have generated counterproductive results. Since many reforms of property-rights systems are based on a conventional theory of how property-rights systems affect the incentives of those using natural resource systems, the multiple failures need to be viewed as evidence for an insufficient theoretical understanding of the relationship between diverse forms of property and the incentives and behavior of resource users. The currently accepted theory is based on idealized models of private property and government property. Researchers frequently equate common property with the absence of any property rights.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Conceptual Confusion

The debate about the relative merits of government, private, and common property has been clouded by three confusions. Different meanings are assigned to terms without clarifying how multiple aspects relate to one another. The sources of confusion relate to the differences between (a) common-property and open access regimes, (b) common-pool resources and common-property regimes, and (c) a resource system and the flow of resource units.

1.1 The Confusion Between Common-Property And Open-Access Regimes

Open-access regimes (res nullius)—including the classic cases of the open seas and the atmosphere— have long been considered in legal doctrine as involving no limits on who is authorized to use a resource. If anyone can use a resource, no one has an incentive to conserve their use or to invest in improvements. If such a resource generates highly valued products, then one can expect that the lack of rules regarding authorized use will lead to misuse and overconsumption. Some local grazing areas, inshore fisheries, and forests are effectively open-access resources, but there are many fewer than presumed in contemporary policy literature.

Some open-access regimes lack effective rules defining property rights by default because the resource is not contained within a nation-state or no entity has laid claim successfully to legitimate ownership. Other open-access regimes are the consequence of conscious public policies to guarantee the access of all citizens to the use of a resource within a political jurisdiction. The concept of jus publicum applies to their formal status but effectively these resources are open access. A third type of open-access regime results from the ineffective exclusion of nonowners by the entity assigned formal rights of ownership. In many developing countries, the earlier confusion between open-access and commonproperty regimes has paradoxically led to an increase in the number and extent of local resources that are effectively open access. Common-property regimes controlling access and harvesting from local streams, forests, grazing areas, and inshore fisheries have evolved over long periods of time in all parts of the world, but have rarely been given formal status in the legal codes of newly independent countries.

As concern for the protection of natural resources mounted during the 1960s, many developing countries nationalized all land and water resources that had not yet been recorded as private property. The evolved institutional arrangements that local users had devised to limit entry and use lost their legal standing as a result of the national government claiming ownership. The national governments, however, lacked monetary resources and personnel to monitor the use of these resources effectively. Thus, resources that had been under a de facto common-property regime enforced by local users were converted to a de jure government property regime, but reverted to a de facto open-access regime. When resources that were previously controlled by local participants have been nationalized, state control has frequently proved to be less effective and efficient than control by those directly affected, if not disastrous in its consequences.

1.2 The Confusion Between A Resource System And A Property Regime

To add to the confusion, the term ‘common-property resource’ frequently is used to describe a type of economic good that is better referred to as a ‘commonpool resource.’ Traditional examples of common-pool resources include fisheries, water systems, and grazing lands. The Internet is an example of a common-pool resource enabled by modern technology. All commonpool resources share two attributes of importance for economic activities: (a) it is costly to exclude individuals from using the good either through physical barriers or legal instruments and (b) the benefits consumed by one individual subtract from the benefits available to others (Ostrom et al. 1994). Recognizing a class of goods that shares these two attributes enables scholars to identify the core theoretical problems facing all individuals or groups who wish to utilize such resources for an extended period of time. Using ‘property’ in a term that refers to a type of good reinforces the impression that goods sharing these attributes tend everywhere to share the same property regime, a notion that is empirically incorrect.

Common-pool resources share with public goods the difficulty of developing physical or institutional means of excluding beneficiaries. Unless means are devised to keep nonauthorized appropriators (those who harvest from the resource) from benefiting, the strong temptation to free ride on the efforts of others will lead to a suboptimal investment in improving the resource, monitoring use, and sanctioning rule-breaking behavior. Second, the products or resource units from common-pool resources share with private goods the attribute that one person’s consumption subtracts from the quantity available to others. Thus, commonpool resources are subject to problems of congestion, overuse, and potential destruction unless harvesting or use limits are devised and enforced. In addition to sharing these two attributes, particular common-pool resources differ on many other attributes that affect their economic usefulness including their size, shape, and productivity and the value, timing, and regularity of the resource units produced.

Common-pool resources may be owned by national, regional, or local governments, by communal groups, or by private individuals or corporations, or they may be used as open-access resources by whomever can gain access. Each of the broad types of property regimes has different sets of advantages and disadvantages, but at times may rely upon similar operational rules regarding access and use of a resource. Examples exist of both successful and unsuccessful efforts to govern and manage common-pool resources by governments, communal groups, cooperatives, voluntary associations, and private individuals or firms (Bromley et al. 1992). No automatic association of commonpool resources exists with common-property regimes or with any other particular type of property regime.

1.3 The Confusion Between The Resource And The Flow Of Resource Units

Common-pool resources are composed of resource systems and a flow of resource units or benefits from these systems. The resource system (or alternatively, the stock or the facility) is what generates a flow of resource units or benefits over time. As mentioned above, examples of typical common-pool resource systems include lakes, rivers, irrigation systems, groundwater basins, forests, fishery stocks, and grazing areas. Common-pool resource systems may also be facilities that are constructed for joint use, such as mainframe computers and the Internet. The resource units or benefits from a common-pool resource include water, timber, medicinal plants, fish, fodder, central processing units, and connection time. Devising property regimes that effectively allow sustainable use of a common-pool resource requires some rules that limit access to the system and other rules that limit the amount, timing, and technology used to withdraw diverse resource units from the resource system. Both types of rules are essential if a resource and its flow are to be managed sustainably.

1.4 Property As Bundles Of Rights

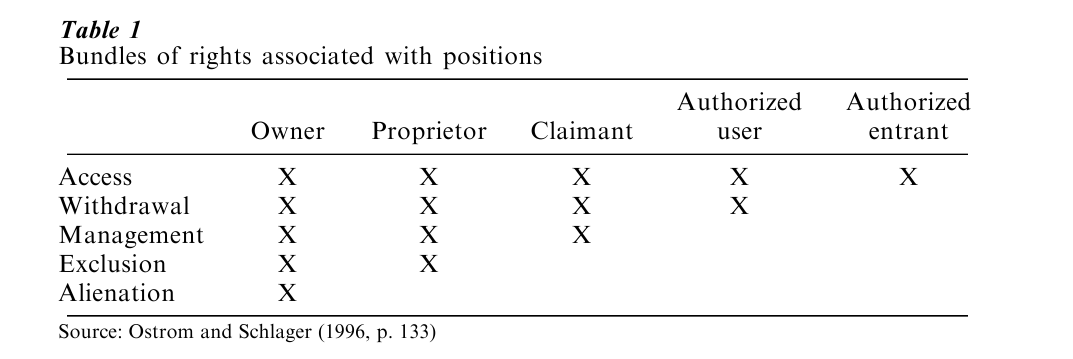

A property right is an enforceable authority to undertake particular actions in a specific domain (Commons 1957). Property rights define actions that individuals can take in relation to other individuals regarding some ‘thing’. If one individual has a right, someone else has a commensurate duty to observe that right. Schlager and Ostrom (1992) identify five property rights that are most relevant for the use of common-pool resources, including access, withdrawal, management, exclusion, and alienation. These are defined as:

(a) Access: the right to enter a defined physical area and enjoy nonsubtractive benefits (e.g., hike, canoe, sit in the sun);

(b) Withdrawal: the right to obtain resource units or products of a resource system (e.g., catch fish, divert water);

(c) Management: the right to regulate internal use patterns and transform the resource by making improvements;

(d) Exclusion: the right to determine who will have an access right, and how that right may be transferred; and

(e) Alienation: the right to sell or lease management and exclusion rights (Schlager and Ostrom 1992).

Private property is frequently defined as being the equivalent of alienation. Property-rights systems that do not contain the right of alienation are considered by many policy analysts to be ill-defined. Further, they are presumed to lead to inefficiency since propertyrights holders cannot trade their interest in an improved resource system for other resources, nor can someone who has a more efficient use of a resource system purchase that system in whole or in part (Demsetz 1967). Consequently, it is assumed that property-rights systems that include the right to alienation will be transferred to their highest valued use.

Instead of focusing on one right, it is more useful to define five classes of property-rights holders as shown in Table 1. In this view, individuals or collectivities may hold well-defined property rights that include or do not include all five of the rights defined above. This approach separates the question of whether a particular right is well defined from the question of the effect of having a particular set of rights. ‘Authorized entrants’ include most recreational users of national parks who purchase an operational right to enter and enjoy the natural beauty of the park, but do not have a right to harvest forest products. Those who have both entry and withdrawal use-right units are ‘authorized users.’ The presence or absence of constraints upon the timing, technology used, purpose of use, and quantity of resource units harvested are determined by operational rules devised by those holding the collective-choice rights (or authority) of management and exclusion. The operational rights of entry and use may be finely divided into quite specific ‘tenure niches’ (Bruce 1999) that vary by season, by use, by technology, and by space. Tenure niches may overlap when one set of users owns the right to harvest fruits from trees, another set of users owns the right to the timber in these trees, and the trees may be located on land owned by still others. Operational rules may allow authorized users to transfer access and withdrawal rights either temporarily through a rental agreement, or permanently when these rights are assigned or sold to others. ‘Claimants’ possess the operational rights of access and withdrawal plus a collective-choice right of managing a resource that includes decisions concerning the construction and maintenance of facilities and the authority to devise limits on withdrawal rights.

2. Can Proprietors As Well As Owners Manage Common-Pool Resources?

‘Proprietors’ hold the same rights as claimants with the addition of the right to determine who may access and harvest from a resource. Most of the property systems that are called ‘common-property’ regimes involve participants who are proprietors and have four of the above rights, but do not possess the right to sell their management and exclusion rights even though they most frequently have the right to bequeath it to members of their family (see Berkes 1989, Bromley et al. 1992, McCay and Acheson 1987).

Empirical studies have found that some proprietors have sufficient rights to make decisions that promote long-term investment and harvesting from a resource. Place and Hazell (1993) conducted surveys in Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda to ascertain if indigenous landright systems were a constraint on agricultural productivity. They found that land users having the rights of a proprietor as contrasted to an owner in these settings made as efficient investment decisions and were as productive. Other studies conducted in Africa (Migot-Adholla et al. 1991, Bruce and Migot-Adholla

1994) also found little difference in productivity, investment levels, or access to credit as well as in land tenure regimes and intensity of cultivation (Turner et al. 1993). In densely settled regions, however, proprietorship over agricultural land may not be sufficient (Feder et al. 1988, Feder and Feeny 1991). In a series of studies of inshore fisheries, self-organized irrigation systems, forest user groups, and groundwater institutions, proprietors tended to develop strict boundary rules to exclude noncontributors; established authority rules to allocate withdrawal rights; devised methods for monitoring conformance; and used graduated sanctions against those who did not conform to these rules (Agrawal 1994, Blomquist 1992, Schlager 1994, Lam 1998). ‘Owners’ possess the right of alienation—the right to transfer a good in any way the owner wishes that does not harm the physical attributes or uses of other owners—in addition to the bundle of rights held by a proprietor. An individual, a private corporation, a government, or a communal group may possess full ownership rights to any kind of good including a common-pool resource. The rights of owners, however, are never absolute. Even private owners have responsibilities not to generate particular kinds of harms for others. In conventional theory it is always presumed that owners will manage the resources they own efficiently. This does not mean, however, that owners are more likely than proprietors to manage resources in a sustainable manner. Sustainability requires restricting the use of the flow to the ‘sustainable yield,’ which may or may not be the efficient level (Clark 1980). Thus, the private owner of a common-pool resource may efficiently ‘use up’ a resource when the value of the flow is high and the future is discounted at conventional levels.

The world of property rights is, thus, far more complex than simply government, private, and common property. These terms better reflect the status and/or ganization of the holder of a particular right than the bundle of property rights held. All of the above rights can be held by single individuals or by collectivities. Some communal fishing systems grant their members all five of the above rights, including the right of alienation (Miller 1989). Members in these communal fishing systems have full ownership rights. Similarly, farmer-managed irrigation systems in Nepal, the Phillippines, and Spain have established transferable shares to the systems. Access, withdrawal, voting, and maintenance responsibilities are allocated by the amount of shares owned (Martin and Yoder 1983, Siy 1982, Maass and Anderson 1986). On the other hand, some proposals to ‘privatize’ inshore fisheries through the devise of an Individual Transferable Quota (ITQ) allocate transferable use rights to authorized fishers but do not allocate rights related to the management of the fisheries, the determination of who is a participant, nor the transfer of management and exclusion rights. Thus, proposals to establish ITQ systems, which frequently are referred to as forms of ‘privatization’, do not involve full ownership.

Further, all three types of owners may fail to manage common-pool resources in a sustainable manner. The possibility that individuals who jointly own a resource system and govern and manage that resource in a sustainable manner has only been seriously recognized the 1980s. Prior to that there were many individual studies that documented individual ‘success’ cases, but these were treated as relatively unique cases and not representing any more general phenomena. While the number of successful instances of self-organized resource systems now appears to be very large, it is also the case that some communities do not organize themselves to develop indigenous property rights systems. When the resources they jointly use are valuable, the lack of self-organization can, indeed, lead to tragic overuse, if not the destruction of the resource system. Thus, the question of why some groups organize and others do not organize is key to an understanding of common-property institutions and the environment.

3. On The Origin Of Self-Governed Common-Pool Resources

Recent research, thus, challenges the generalizability of the conventional theory that predicts that no one will organize to ensure the long-term sustainability of a jointly used natural resource system. While the conventional theory is generally successful in predicting outcomes in settings where appropriators are alienated from one another or cannot communicate effectively, it does not provide an explanation for settings where appropriators are able to create and sustain agreements to avoid serious problems of over appropriation. Nor does it predict well when government ownership will perform appropriately or how privatization will improve outcomes. A fully articulated, reformulated theory encompassing the conventional theory as a special case does not yet exist. On the other hand, scholars familiar with the results of field research substantially agree on a set of variables that enhance the likelihood of appropriators organizing themselves to avoid the social losses associated with open-access, common-pool resources (McKean 2000, Wade 1994, Ostrom 1990, Baland and Platteau 1996). Considerable consensus exists that the following attributes of resources and of appropriators are conducive to an increased likelihood that self-governing associations will form.

3.1 Attributes Of The Resource

3.1.1 Feasible Improvement. Resource conditions are not at a point of deterioration such that it is useless to organize or so underutilized that little advantage results from organizing.

3.1.2 Indicators. Reliable and valid indicators of the condition of the resource system are frequently available at a relatively low cost.

3.1.3 Predictability. The flow of resource units is relatively predictable.

3.1.4 Spatial Extent. The resource system is sufficiently small, given the transportation and communication technology in use, that appropriators can develop accurate knowledge of external boundaries and internal microenvironments.

3.2 Attributes Of The Appropriators

3.2.1 Salience. Appropriators are dependent on the resource system for a major portion of their livelihood or other important activity.

3.2.2 Common Understanding. Appropriators have a shared image of how the resource system operates and how their actions affect each other and the resource system.

3.2.3 Low Discount Rate. Appropriators use a sufficiently low discount rate in relation to future benefits to be achieved from the resource.

3.2.4 Trust And Reciprocity. Appropriators trust one another to keep promises and relate to one another with reciprocity.

3.2.5 Autonomy. Appropriators are able to determine access and harvesting rules without external authorities countermanding them.

3.2.6 Prior Organizational Experience And Local Leadership. Appropriators have learned at least minimal skills of organization and leadership through participation in other local associations or learning about ways that neighboring groups have organized.

4. The Importance Of Larger Political Regimes

It is important to stress that many of these variables are affected strongly by the type of larger political regime in which appropriators are embedded. Larger regimes can facilitate local self-organization by providing accurate information about natural resource systems, providing arenas in which participants can engage in discovery and conflict-resolution processes, and providing mechanisms to back up local monitoring and sanctioning efforts. Perceived benefits of organizing are greater when users have accurate information about the threats facing a resource. The costs of monitoring and sanctioning those who do not conform to rules devised by users are very high, when the authority to make and enforce these rules is not recognized. Thus, the probability of participants adopting more effective rules in macro regimes that facilitate their efforts over time is higher than in regimes that ignore resource problems entirely or, at the other extreme, presume that all decisions about governance and management need to be made by central authorities. If local authorities are not formally recognized by larger regimes, it is difficult for users to establish an enforceable set of rules. On the other hand, if rules are imposed by outsiders without consulting local participants in their design, local users may engage in a game of ‘cops and robbers’ with outside authorities.

5. Conclusion

The conventional theory of common-pool resources, which presumed that external authorities were needed to impose new rules on those appropriators trapped into producing excessive externalities on themselves and others, is now considered a special case of a more general theoretical structure. For appropriators to reformulate the institutions they face, they have to expect that the benefits they receive from an institutional change will exceed the immediate and long-term expected costs. When appropriators cannot communicate and have no way of gaining trust through their own efforts or with the help of the macro institutional system within which they are embedded, the prediction of the earlier theory is likely to be empirically supported. Ocean fisheries, the stratosphere, and other global commons come closest to the appropriate empirical referents (Ostrom et al. 1999). If appropriators can engage in face-to-face bargaining and have autonomy to change their rules, they may well attempt to organize themselves. Whether they organize depends on attributes of the resource system and the appropriators themselves that affect the benefits to be achieved and the costs of achieving them. Whether their self-governed enterprise succeeds over the long-term depends on whether the institutions they design are consistent with design principles underlying robust, long-living, self-governed systems. The theory of common-pool resources has progressed substantially during the second half of the twentieth century. There are, however, many challenging puzzles still to be solved.

Bibliography:

- Agrawal A 1994 Rules, rulemaking, and rule breaking: examining the fit between rule systems and resource use. In: Ostrom E, Gardner R, Walker J M (eds.) Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI

- Baland J M, Platteau J P 1996 Halting Degradation of Natural Resources. Is There a Role for Rural Communities? Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Berkes F (ed.) 1989 Common Property Resources; Ecology and Community-based Sustainable Development. Belhaven Press, London

- Blomquist W 1992 Dividing the Waters: Governing Groundwater in Southern California. ICS Press, San Francisco

- Bromley D W, Feeny D, McKean M, Peters P, Gilles J, Oakerson R, Runge C F, Thomson J (eds.) 1992 Making the Commons Work: Theory, Practice, and Policy. ICS Press, San Francisco

- Bruce J 1999 Legal Bases for the Management of Forest Resources as Common Property. Community Forestry Note 14. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

- Bruce J W, Migot-Adholla S E (eds.) 1994 Searching for Land Tenure Security in Africa. Kendall Hunt, Dubuque, IA

- Clark C W 1980 Restricted access to common-property fishery resources: A game theoretic analysis. In: Lin P T (ed.) Dynamic Optimization and Mathematical Economics. Plenum Press, New York

- Commons J R 1957 Legal Foundations of Capitalism. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI

- Demsetz H 1967 Toward a theory of property rights. American Economic Review 57: 347–59

- Feder G, Feeny D 1991 Land tenure and property rights: Theory and implications for development policy. World Bank Economic Review 5(1): 135–53

- Feder G, Onchan T, Chalamwong Y, Hangladoran C 1988 Land Policies and Farm Productivity in Thailand. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD

- Lam W F 1998 Governing Irrigation Systems in Nepal: Institutions, Infrastructure, and Collective Action. ICS Press, Oakland, CA

- Maass A, Anderson R L 1986 … and the Desert Shall Rejoice: Conflict, Growth, and Justice in Arid Environments. Krieger, Malabar, FL

- Martin E, Yoder R 1983 Review of farmer-managed irrigation in Nepal. In: Martin G, Yoder R (eds.) Water Management in Nepal: Proceedings of the Seminar on Water Management Issues, July 31–August 2. Ministry of Agriculture, Agricultural Projects Services Centre, and the Agricultural Development Council, Kathmandu, Nepal

- McCay B J, Acheson J M (eds.) 1987 The Question of the Commons: The Culture and Ecology of Communal Resources. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, AZ

- McKean M A 2000 Common property: what is it, what is it good for, and what makes it work? In: Gibson C C, McKean M P, Ostrom E (eds.) People and Forests: Communities, Institutions, and Governance. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Migot-Adholla S, Hazell P, Blarel B, Place F 1991 Indigenous land rights systems in sub-Saharan Africa: A constraint on productivity? World Bank Economic Review 5(1): 155–75

- Miller D 1989 The evolution of Mexico’s spiny lobster fishery. In: Berkes F (ed.) Common Property Resources: Ecology and Community-Based Sustainable Development. Belhaven, London

- Ostrom E 1990 Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Ostrom E, Burger J, Field C B, Norgaard R B, Policansky D 1999 Sustainability – Revisiting the commons: local lessons, global challenges. Science 284(5412) (April 9): 278–82

- Ostrom E, Gardner R, Walker J M 1994 Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI

- Ostrom E, Schlager E 1996 The formation of property rights. In: Hanna S, Folke C, Maler K-G (eds.) Rights to Nature. Island Press, Washington, DC

- Place F, Hazell P 1993 Productivity effects of indigenous land tenure systems in sub-Saharan Africa. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 75: 10–19

- Schlager E 1994 Fishers’ institutional responses to commonpool resource dilemmas. In: Ostrom E, Gardner R, Walker J M (eds.) Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI

- Schlager E, Ostrom E 1992 Property rights regimes and natural resources: A conceptual Analysis. Land Economics 68(3): 249–62

- Siy R Jr. Y 1982 Community Resource Management: Lessons from the Zanjera. University of the Philippines Press, Quezon City, Philippines

- Turner II B L, Hyden G, Kates R (eds.) 1993 Population Growth and Agricultural Change in Africa. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL

- Wade R 1994 Village Republics: Economic Conditions for Collective Action in South India. ICS Press, San Francisco