Sample Environmental Vulnerability Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, chech our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Global changes are accelerating at an ever increasing pace with varying impacts. While some societies are becoming more globalized and equipped with modern technology, others live in poverty, they struggle to survive amidst the challenges of fluctuating daily provisions, inadequate shelter, and poor provision of essential services including health and water. Both societal groups may confront environmentally vulnerable situations. People living in industrialized cities may, for example, have to encounter technological hazards (e.g., toxic chemical accidents) and those living in less-developed locations may be at risk of poorly constructed homes and inadequate basic services provision such as water (White 1974, Kates et al. 1985).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

A host of practitioners (nongovernment organizations, relief workers, disaster managers), scientists, academics, and policy makers are endeavoring to understand the processes that shape the welfare and daily conditions of people and how their lives are influenced by environmental change. One way of trying to understand what enables some to better manage changing events is through a careful probing and examination of ‘environmental vulnerability.’ In this research paper environmental vulnerability will be examined particularly from the perspective of human vulnerability. Environmental vulnerability will be defined followed by examples of how the concept has changed and been used over time.

1. Defining Environmental Vulnerability

There have been several attempts to define and capture what is meant by environmental vulnerability ranging from geophysical, engineering, and technological aspects of environmental vulnerability through to the social, political, economic, and political dimensions. In the 1970s and 1980s, the importance of integrating these dimensions as a means to understand how such factors shape people’s lives and their exposure and vulnerability to changing environments was recognized. This thinking influenced the generation of theories and concepts that were subsequently adopted in the lexicons of development, disaster management, and in global change science. One key concept which reflects this holistic view is environmental vulnerability.

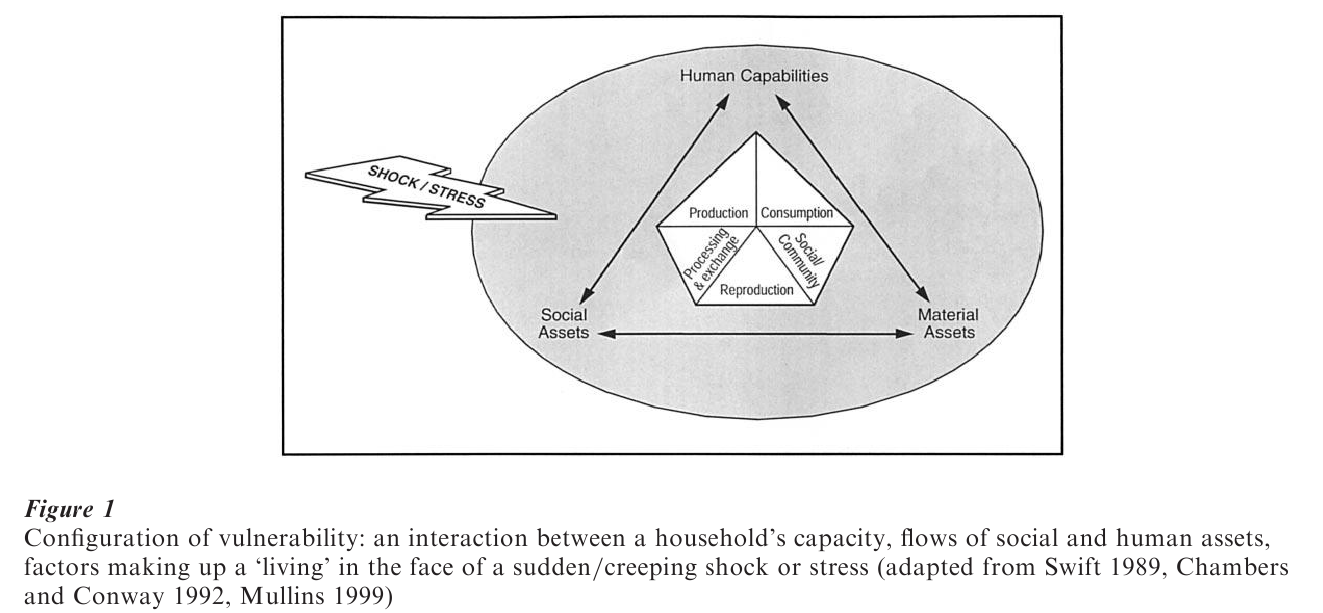

Environmental vulnerability is the product of a combination of circumstances related to a host of issues which include living with risks and hazards (sudden events such as floods, earthquakes, and slow-onset events such as droughts). Other factors such as health, poverty, and gender also exacerbate existing risks/hazards, thereby heightening vulnerability and weakening positive responses to such phenomena. Environmental vulnerability is thus described with reference to the physical and social environment or the milieu in which a group may find themselves (Fig. 1).

Having briefly described what is meant by environmental vulnerability, the focus now shifts to examine how it is used in a variety of contexts. In some fields, environmental vulnerability is associated with geophysical aspects of risk and ‘hazard science.’ In many cases, however, particularly those characterized by poverty, certain risks, hazards, and potential disasters are not only linked to natural events but also related to slow, continuous processes that are advanced by environmental and socioeconomic vulnerability. In these regions, ‘traditional’ hazard risk analyses are often compounded by other mitigating factors such as lack of access to resources, lack of accessible information, reduced response to shocks because of poverty or other factors. Recognizing this complexity, a strong emphasis on the human dimensions of vulnerability has emerged which describes both internal dimensions (inability or ability to cope and respond) and external dimensions (such as exposure to risk, shocks, and stress) (e.g., Chambers 1989, Swift 1989, Liverman 1990, Chambers and Conway 1992, Blaikie et al. 1994, Cutter 1996, Downing et al. 1996, Hewitt 1997). From this perspective, ‘vulnerability’ is not an absolute term but is a relational or social term. Vulnerable groups or regions are therefore those most exposed to a disturbance but who also possess a limited array of ‘response mechanisms’ or coping capabilities to respond to the event, crisis, or disturbance. Vulnerability also includes a ‘sense of powerlessness’ and has been described as a ‘measure’ of defenselessness and insecurity in the face of a crisis. Poor refugees, for example, dislocated from their families and family networks, lacking adequate shelter and forced to inhabit environmentally risky areas, would be most vulnerable to a sudden shock event such as an outbreak of cholera, a flood, or an earthquake.

These examples illustrate the complex nature of vulnerability and they also show how difficult it is to untangle the causes of vulnerability from a complex set of social and physical factors. They also illustrate the importance of rigorous analysis in unbundling the complex interplay between those components which shape and contribute to vulnerability (e.g., economic restructuring measures, violence and intimidation, health issues, loss of livelihoods, environmental degradation, and rapid technological development). For instance, several vulnerability assessments in poor regions examine a household’s assets, ‘bundles of goods,’ capacities and abilities to respond to events, plus how these change or evolve over time.

Assessments of environmental vulnerability have also expanded to include the investigation of elements of both time and space. A group may, for example, become increasingly more vulnerable to an event as their coping responses become eroded over time. In several countries, HIV AIDS, conflict, and violence are insidious, everyday factors that heighten vulnerability during times of shock or stress such as drought. Inter and intraregional variations in environmental vulnerability also exist (see Kasperson et al. 1995). Some have therefore called for a multilayered approach when examining environmental vulnerability which involves various measurements to produce assessments of environmental vulnerability.

2. Measuring Vulnerability In An Environmental Context

Different organizations, scientists, and others have experimented and used an array of approaches and techniques to try and measure or target ‘vulnerable groups.’ Some of these include identifying indicators of vulnerability including vegetation change, flood and drought risk, food access and availability, and/or malnutrition. Methods and frameworks from which one can identify vulnerability have often been the product of a borrowing and a ‘stitching’ together of related approaches attempting to identify ‘vulnerable environments’ or ‘regions of risk.’ By using a variety of methods, maps of vulnerability highlighting those areas and groups that may be at social, physical, and/or economic risk have been compiled (see Davies 1996, Kasperson et al. 1995). The dynamic nature of vulnerability, however, dictates that measurements of vulnerability have to be flexible and often include qualitative as well as quantitative techniques. The sustainable livelihoods approach has been used extensively in several parts of the world as a means to identify areas and groups that are vulnerable. In this approach the environment is seen to include both physical and social dimensions.

2.1 Sustainable Livelihoods Approach—Accessing A Measure Of Vulnerability

A complex array of capabilities, resilience, and vulnerabilities are viewed collectively in the concept of sustainable livelihoods (see Chambers and Conway 1992, Carney 1998). This approach has become a very popular way of trying to gain a sense of the vulnerability and resilience of a community and its environment, particularly among those working in third world rural and urban contexts. The focus in such an approach is to try and determine how people live and make a living and from there try and capture those factors that may be undermining peoples’ ability to produce a livelihood. In this approach people and their livelihoods are viewed together with their stores and resources (tangible assets e.g., land, water, trees and livestock, farm equipment, tools, etc.) and their claims and resources (intangible assets e.g., local networks such as relatives) within a specified environment.

In such ways livelihood analysis examines the resilience of an array of household strategies in the face of environmental change. This approach has been used in several country and household studies by, for example, organizations such as Care International, USAID, Oxfam, Save the Children Fund (UK), and others. A central element of such investigations has been to examine the interplay between the environment (e.g., such factors as land use management) and households at risk and explores how environmental factors complement or detract from flows of goods, services, and assets into a household, making such households more vulnerable or resilient to change. Environmental degradation, associated with deforestation, desertification, poor water, and land use management may, for example, prevent a household from being able to farm and/or derive some benefit from the environment. A degraded environment may also heighten the risk of landslides, flooding, and other disasters.

3. Themes In Environmental Vulnerability

The last few paragraphs have been used to illustrate what is meant by the concept environmental vulnerability and how it can be used. This discussion is now extended to illustrate how environmental vulnerability has been used in various fields. Assessments of environmental vulnerability have collectively framed wider dialogue and discussion and provided a focal point in the fields of food security, climate and global change, environmental resource management, and disaster management. The focus over time for those using environmental vulnerability to inform food security has evolved to include a more holistic understanding of vulnerability. In this field, the locus of attention has moved beyond the examination of the numbers of people affected, their daily food caloric requirements, and tons of food available. Today, such efforts converge on the ‘real people’ including attempts to capture the daily suite of activities that people use to live and often to survive together with those factors that may undermine or encroach on these capacities. Vulnerability and chronic food insecurity, therefore, could potentially be driven by policy failures (e.g., war, economic strategies); resource poverty bad luck, disaster (e.g., environmental hazards, asset distribution); as well as ‘population transition’ (e.g., demographic growth) (see Watts and Bohle 1993, Ribot et al. 1996).

As groups are compelled to exert greater pressures on resources in order to adjust, manage and, in some cases, survive, they may negatively shape and impact on their physical environment. Recognizing this relationship, development practitioners, scientists, and others have begun to adapt the concept to improve our understanding of these interactions. Sustainable resource utilization is being understood through the lens of environmental vulnerability. Some are using various interpretations of vulnerability to understand and unravel how institutions and issues of access and entitlement to resources shape and configure various environments (e.g., Leach et al. 1997). Access to natural resources such as trees, plants, grasses, which are exchanged for currencies and enable people to make a living, may be controlled by institutions at various levels (e.g., governments, state policies, relations within households). The strength of this institutional control may preclude individuals or groups gaining access to the resources they use and which in turn may heighten their vulnerability during times of need, shock, stress, or in changing environmental conditions.

Other practitioners including nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), governments, humanitarian, and relief agencies have also begun articulating their understanding of vulnerability as an integral component of disaster risk. Here vulnerability is used to inform mitigatory and risk-reduction measures to offset disasters. Organizations including The International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Catholic Relief Services, Save the Children Fund, and several disaster management and risk reduction networks, including those established in South America (e.g., LA RED), in southern Africa (PeriPeri), and in South Asia (e.g., Duryog Nivaran), are asking ‘Why are some people and groups more vulnerable to disasters than others?’ (e.g., Ariyabandu 1999, Holloway 1999). This focus on vulnerability and risk reduction to disasters has been underscored at the international level as one of the tenets underpinning the United Nations General Assembly Resolution (44/236) adopted in 1989 when the decade 1990–2000 was declared the International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction (IDNDR).

The growing interest in vulnerability in recent years can be largely attributable to the variety of entry points that ‘environmental vulnerability’ gives those in fields influenced by the social and biophysical context of environmental change. When a sensitive understanding of vulnerability has been obtained then, it is argued, this knowledge can be used to inform a variety of interventions including development policy which incorporates disaster-related strategies. Several notions of vulnerability are therefore being crafted together into discourses on poverty (in both rural and urban settings), food security, disasters, rural and urban livelihoods, and assessments of local and global environments that are at risk. Despite this broad range of interest, environmental vulnerability remains a complex issue, demanding complicated methods to identify environmentally vulnerable groups or regions.

4. Current And Future Potential Usage Of Environmental Vulnerability

Several examples of how environmental vulnerability can be used to inform planning, science, and development work can be found in a number of countries including those in Africa, South America, and South Asia. For example, in Mozambique, government, NGOs, and various other organizations (e.g., United Nations World Food Program) have used a vulnerability analysis and mapping (VAM) approach to demarcate and identify those areas and groups that are vulnerable. By using geographical information systems and other mapping techniques, areas that are prone to flood risk, rainfall shortage, suffer from poor vegetation and where food availability and food access are problems have been identified. This information is not only useful to define vulnerable areas but can also be used to inform and help target efforts by policy makers and other organizations that may be involved in development work.

In South Asia, disaster and risk-reduction networks such as Duryog Nivaran have been using environmental vulnerability as a concept and the basis for their disaster mitigation work in the region (Ariyabandu 1999). This network has illustrated that environmental vulnerability and mitigation is linked not only to understanding technological factors but also to increased sensitivity of how grass-root communities have used their experience to increase their resilience to risky environmental situations. Close examination of how gender plays a role in either heightening or reducing vulnerability has, for example, highlighted the role that women play in preparing and mitigating disasters such as droughts and cyclones. Through the sharing of their knowledge and experience women have enabled each other to face the challenges of both daily living as well as being strengthened for times of shock associated with extreme weather events.

5. Environmental Vulnerability And The Future

Much has been done, and still remains to be done, to advance and adapt the use of environmental vulnerability assessments to other contexts. Identification of critical thresholds of environmental vulnerability; improved indicators of environmental vulnerability in developed, technological, and developing worlds; and the identification of ways to capture issues of scale and space are current and future areas of interest. How these feed into and are in turn impacted by global change are central priority research areas of several local and international initiatives.

Vulnerability reduction, some have argued, has not been a priority in development and environmental policy and has often been a response to discrete events, linked only to disaster management. A critical area, therefore, is to better integrate environmental vulnerability and vulnerability assessments into development and environmental planning. These efforts will also hopefully assist in mitigating the consequences associated with possible changes in global environment which may accompany a warmer, more crowded, poorer, disaster-prone world.

Notwithstanding the difficulties of trying to understand, profile, and articulate notions of environmental vulnerability, it remains useful for a range of users including hazard/risk scientists, policymakers, donors, relief agents, and development practitioners. The complexity embedded in environmental vulnerability is perhaps its greatest strength because it opens ways for greater interaction, discussion, and discourse in an age of greater globalization and information exchange and one which may bring with it a variety of ‘millennium bugs,’ ‘surprises,’ and ‘new vulnerabilities.’

Bibliography:

- Ariyabandu M M 1999 Defeating Disasters: Ideas for Action. A Duryog Nivaran publication funded by the Conflict and Humanitarian Affairs Department of the Department for International Development, UK (CHAD-DFID)

- Blaikie P, Cannon T, Davis I, Wisner B 1994 At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters. Routledge, London

- Carney D (ed.) 1998 Sustainable Livelihoods: What Contribution Can We Make? Department for International Development, London

- Chambers, R 1989 Editorial introduction: Vulnerability, coping and policy. IDS Bulletin 20(2): 1–7

- Chambers R, Conway G R 1992 Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century. Institute of Development Studies, Discussion Paper, 296, Institute of Development Studies IDS, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK

- Cutter S L 1996 Vulnerability to environmental hazards. Progress in Human Geography 20(4): 529–39

- Davies S 1996 Adaptable Livelihoods: Coping with Food Insecurity in the Malian Sahel. Macmillan

- Downing T, Watts M, Bohle H 1996 Climate change and food insecurity: Toward a sociology and geography of vulnerability. In: Downing T E (ed.) Climate Change and World Food Security. NATO ASI Series, Global Environmental Change, pp. 183–206

- Hewitt K 1997 Regions of Risk a Geographical Introduction to Disasters. Longman

- Holloway A (ed.) 1999 Risk, Sustainable Development and Disasters: Southern Perspectives. University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa (a PeriPeri publication)

- Kasperson J, Kasperson R, Turner B 1995 Regions at Risk. Comparisons of Threatened Environments. The United Nations University Press, Tokyo

- Kates R W, Hohenemser C, Kasperson J X (eds.) 1985 Perilous Progress: Managing the Hazards of Technology. Westview Press, Boulder, CO

- LA RED 1993 The Network for Social Studies on Disaster Prevention: Research Agenda and Constitution. ITDG, Lima, Peru

- Leach M, Mearns R, Scoones I 1997 Environmental Entitlements: A Framework for Understanding the Institutional Dynamics of Environmental Change. Discussion Paper 359, Institute of Development Studies IDS, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK

- Liverman D M 1990 Vulnerability to global environmental change. In: Kasperson R, Dow K, Golding D, Kasperson J (eds.) Understanding Global Environmental Change: The Contributions of Risk Analysis and Management. Clark University, Worcester, MA, pp. 27–44

- Mullins D 1999 Livelihoods and vulnerability analysis: From basic concepts to fieldwork. Paper presented at a conference on Risk, Sustainable Development and Disasters: Perspectives from the South, a PeriPeri Institute initiative, Harare, Zimbabwe, 22 February

- Ribot J C, Magalhaes A R, Panagides S S 1996 Climate Variability, Climate Change and Social Vulnerability in the Semi-arid Tropics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Swift J 1989 Why are rural people vulnerable to famine. IDS Bulletin 20(2): 8–15

- Watts M J, Bohle H G 1993 The space of vulnerability: The causal structure of hunger and famine. Progress in Human Geography 17(1): 43–67

- White G 1974 Natural Hazards: Local, National and Global. Oxford University Press, New York