Sample Environmental Psychology Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, chech our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Environmental psychology is the study of the impact of the physical environment on people and the impact of people on the physical environment. This broad definition will be qualified in several respects to distinguish environmental psychology from psychology in general and from other subfields with similar aims, in disciplines such as human geography, physiology, and sociology. Environmental psychology is also known as an area of applied psychology, although as in many other such areas a substantial proportion of the research is devoted to theoretical and methodological development. Today environmental psychology provides a theoretical and methodological foundation for environmental planning, design, and management.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The first section will briefly outline how environmental psychology developed historically. A problem conceptualization follows which is used to define focuses of the environmental psychology research. Finally, some of the major research focuses are described.

1. Historical Development

Transformation of the earth’s surfaces by human beings has a long history. A primary aim is to create protection against threats to survival. In the 1960s the scientific study of the psychological effects of the humanmade environment began, largely motivated by a concern for the deterioration of human environments (e.g., Proshansky et al. 1970). A sensible early approach was to compare psychological effects of the humanmade environment with those of the natural environment in which the human species evolved.

Research strategies in environmental psychology were first outlined by Craik (1968), based on the dominant strategy in personality assessment. Measurement issues were naturally at the forefront in the early research in environmental psychology. In particular, it was necessary for progress that methods were developed to assess physical settings outside the psychological laboratory as well as to assess how people react to such settings.

Important substantive research problems were originally defined by design professionals whose training made them sensitive to many subtle effects of the designed environment on human behavior. They used this knowledge in designing environments. However, in the face of criticism they became concerned about the scientific basis of their work. Social scientists observed a decline in the quality of urban life. To physiological psychologists this opened new meaningful research problems of how health and well-being are related to the physical environment. Cognitive psychologists concerned about the ecological validity of their research discovered in environmental psychology the possibility for investigating the acquisition, representation, and use of everyday knowledge (of the physical environment). Social psychologists saw in environmental psychology a way out of the laboratory to do meaningful research in the real world. Since the new focus on the physical environment did not stop them from analyzing the social environment, they offered influential conceptualizations in which the physical environment is presupposed to interact with the social environment in shaping human behavior.

The history of environmental psychology as well as its current status is documented in a series of comprehensive reviews published in Annual Review of Psychology, see, for example, Sundstrom et al. (1996). In 1987 the Handbook of Environmental Psychology was published under the editorship of Daniel Stokols and Irwin Altman. Following this benchmark publication several edited series of books have appeared with reviews of research in different subfields (e.g., Zube et al. 1987–97). Current research is primarily disseminated in three journals with slightly different emphases: Journal of Environmental Psychology, edited by David Canter, represents the psychological perspective; Environment and Behavior, edited by Robert Bechtel, covers the broader interdisciplinary field of environment–behavior research; and Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, edited by Andrew Seidel, is primarily an outlet for architectural and environmental design research. Several textbooks have also been written. The most comprehensive of these (Gifford 1997) cites approximately 5,000 studies.

2. Problem Conceptualization

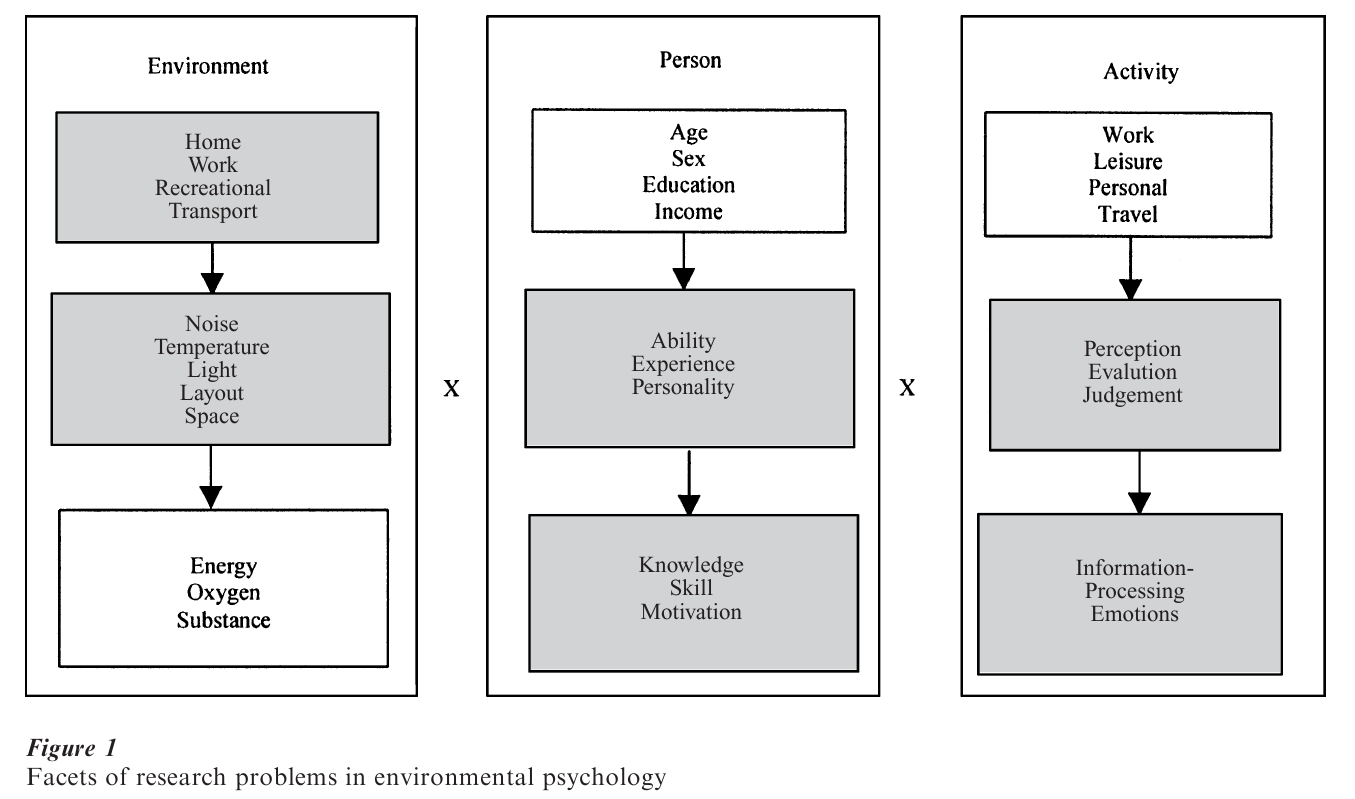

A research problem in environmental psychology has three facets: the environment, the person or group, and the activity the person or group is engaged in. Any of these facets may be analyzed at different depths, ranging from what may be termed a molar to a molecular level.

So, for instance, the environment may be conceived of as consisting of different molar types (e.g., home, workplace). They are partly defined by their spatial extension, partly by their function. Any such type of environment may furthermore be analyzed at the level of stimuli (e.g., noise, temperature) impinging on people. These two levels are the primary concern to environmental psychology. At a still lower level the physical characteristics of stimuli may be analyzed. This level is sometimes the focus when changes of the other levels are the goal, for instance, in constructing new environments.

Sociodemographic characteristics of people occupying environments are seldom a primary concern to environmental psychology whereas psychological characteristics are. Such characteristics include more stable ones referred to as abilities, attitudes, and personality traits. More transient characteristics such as knowledge, skill, and motivation are also of interest to environmental psychology.

Activities are clearly important as people’s means for achieving goals. They are sometimes analyzed at the level of general function (e.g., work, leisure). However valuable this is, the main focus of environmental psychology is psychologically deeper. Here invariant components of all activities (e.g., perception, evaluation) are emphasized. Sometimes the focus is even on subcomponents of these component processes such as information processing stages or component emotional reactions.

At the psychologically most shallow level a study might focus, for example, on how sociodemographic factors are related to choice of leisure activities in the home. An in-depth study might instead focus on how noise levels affect information processing and mood in the workplace. Environmental psychology differs from psychology in general by its primary focus on molar environments (the filled boxes in Fig. 1), frequently also allowing longer exposures to the environment than is usual in most psychological research. Its focus on intraperson psychological processes distinguishes environmental psychology from other subfields in the disciplines of human geography, physiology, and sociology which study the effects of molar environments. It also differs from these subfields in going beyond sociodemographic factors with the aim of disentangling the ways ability, attitude, personality, knowledge, skill, and motivation modify how individuals react to the molar environment and how differences in intraperson psychological processes mediate such moderator effects.

3. Research Focuses

In this section three general areas of past and current environmental psychology research are described, highlighting in each a few major research focuses.

3.1 Choice Of The Environment

Individuals either choose or are forced to choose where to be. This choice of environment may have profound future consequences for themselves and others. One research focus in environmental psychology is the choice itself. What characteristics of an environment make a person with certain characteristics choose this environment? What characterizes the choice process? Is it deliberate, habitual, or forced?

Research on environmental choice emphasizes different time scales. Some environmental psychology research targets residential choice and migration with possibly lifelong consequences (Aragones et al. 2001). This is also a traditional area of research in social sciences such as economics, human geography, and sociology. A more frequent research focus with a shorter time scale is the study of people’s daily choices of activity areas in the environment where they live, such as shopping locations, recreational facilities, and others. The demand for travel that such choices generate is being studied. In addition, field and laboratory studies investigate acquisition, representation, and use of both spatial and nonspatial knowledge of environments. This research on cognitive maps has expanded in different directions. As evidenced by a recent major publication (Golledge 1999), it now attracts research interests also from cognitive and computer scientists, human geographers, neuroscientists, and zoologists. Another marker is the interdisciplinary journal Spatial Cognition and Computation under the editorship of Patrick Olivier and Stephen Hirtle. Primarily from the perspective that people are cost minimizers, Garling and Golledge (2000) review and analyze research on how location choices depend on the degree and quality of spatial and nonspatial knowledge of the environment. A general conclusion is that this knowledge is always incomplete, is hierarchically organized, and therefore differentially accessible in the choice process. A complementary conceptualization of how knowledge and preferences may be integrated in environmental choices is offered by Canter (1991) who sees action goals as primarily driving preferences.

3.2 Impacts Of The Environment

A large number of psychological and other effects of physical environments on human beings are assumed or expected and have been empirically demonstrated. Some of these effects are relatively direct, whereas others are modified by person characteristics and mediated by intraperson psychological processes. The social environment is another mediator of effects of the physical environment.

In large part because of its potential health outcomes, a dominating research focus in environmental psychology concerns the detrimental effects of environmental stressors such as noise, crowding, and extreme temperatures (Evans 1982) as well as threats of natural disasters, technological catastrophes, or accidents (Baum et al. 1983). Such effects are extensively documented in self-report, physiological, and performance measures. A complementary research focus which more recently has attracted attention is the study of beneficial effects of environments, for instance, the restorative (Kaplan and Kaplan 1989) and stress-reducing potentials of the natural environment (Ulrich 1983). The recurrent finding that sensory deprivation may have positive effects (Suedfeld 1980) bears theoretically on this current research with important practical implications.

Another research focus is the study of groups of people acting and interacting in physical settings. The impact of the physical environment is sometimes mediated by the social environment (e.g., Wicker 1979), for instance, when scarcity of space leads to excessive social interaction with adverse consequences. In other cases the physical environment facilitates social contact with positive effects on, for instance, residential satisfaction.

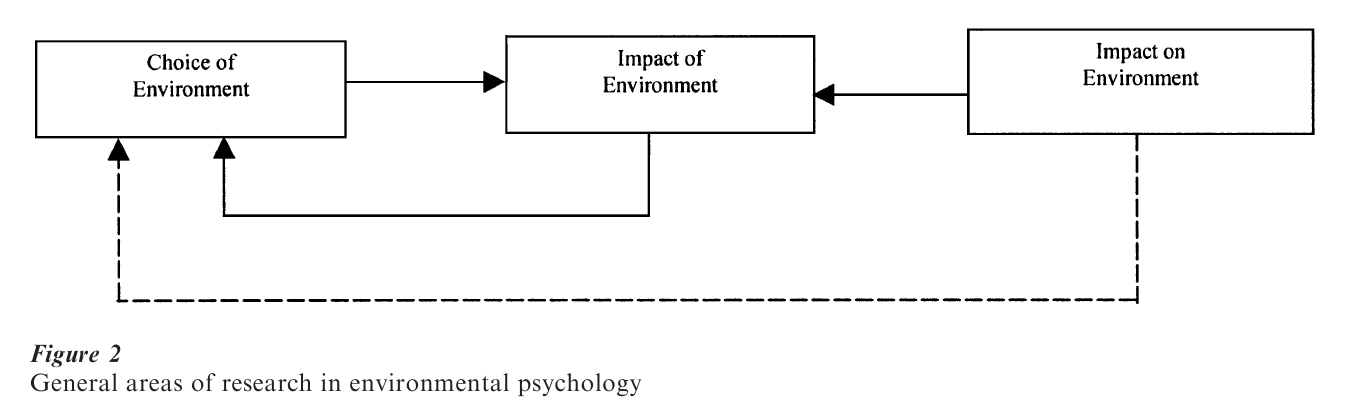

3.3 Impacts On The Environment

Since the early 1990s the scope of environmental psychology has broadened to include the study of methods to promote proenvironmental behaviors so that the detrimental impacts of people on the physical environment may be significantly reduced (Stern 1992). Extending a conceptual framework proposed by Russell and Ward (1982), a possible integration of this new research focus in environmental psychology with the traditional ones may be achieved as shown in Fig. 2. Forced or unforced choice of the environment has psychological consequences for the person. At the same time these choices have impacts on the environment, frequently negative when they are aggregated across many people. Sometimes there are regulatory feedback loops, such as when, for instance, crowding in an environment reaches intolerable levels. In other cases, however, the harmful effects only materialize in the future. Feed-forward loops (the broken arrow) should be provided so that people take these future consequences into account when making their choices. Yet, changing behavioral antecedents and consequences has not in general been a successful method. Current research therefore focuses on different sets of determinants of proenvironmental behaviors such as habits, attitudes, moral concerns, and value orientations. This is likely to lead eventually to both a deeper understanding of behavioral change mechanisms and more effective methods of changing behavior.

4. Forecasting The Future

There are few reasons to believe that the current environmental problems of pollution and resource overuse will soon be solved. It is more likely that demand will increase on environmental psychology to contribute to solutions. Acceptance of new sustainable technologies such as zero-emission vehicles is one salient research focus in the future. One may also see more collaboration with economists, political scientists, and sociologists in developing effective methods for promoting proenvironmental behaviors (e.g., Foddy et al. 1999).

The development of telecommunication technology may have profound influences on how the physical environment will be organized in the future. Transformations of homes into workplaces are already taking place. Electronic shopping is increasing in frequency. To forecast the effects on people is a challenging future task.

The design of intelligent buildings with many automatically performed functions poses new research tasks in the immediate future. Although these new features are basically of benefit to users, people may still react negatively because of loss of perceived control. Also, automatic control may not always work—so users must know how to take over.

Bibliography:

- Aragones J I, Francescato G, Garling T (eds.) 2001 Residential Environments: Choice, Satisfaction, and Behavior. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT

- Baum A, Fleming R, Davidson L M 1983 Natural disaster and technological catastrophe. Environment and Behavior 15: 333–54

- Canter D 1991 Understanding, assessing, and acting in places: Is an integrative framework possible? In: Garling T, Evans G W (eds.) Environment, Cognition, and Action. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 191–209

- Craik K H 1968 The comprehension of the physical environment. American Institute of Planners 34: 29–37

- Evans G W (ed.) 1982 Environmental Stress. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Foddy M, Smithson M, Hogg M, Schneider S (eds.) 1999 Resolving Social Dilemmas. Psychology Press, Philadelphia, PA

- Garling T, Golledge R G 2000 Cognitive mapping in spatial decision making. In: Kichin R, Freundschuh S (eds.) Cognitive Mapping. Routledge, London, pp. 44–65

- Gifford R 1997 Environmental Psychology, 2nd edn. Allyn and Bacon, Boston

- Golledge R G (ed.) 1999 Wayfinding Behavior. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD

- Kaplan R, Kaplan S 1989 The Experience of Nature. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Proshansky H M, Ittelson W H, Rivlin L G (eds.) 1970 Environmental Psychology. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, New York

- Russell J A, Ward L M 1982 Environmental psychology. Annual Review of Psychology 33: 651–88

- Stern P C 1992 Psychological dimensions of global environmental change. Annual Review of Psychology 43: 269–302

- Stokols D, Altman I (eds.) 1987 Handbook of Environmental Psychology. Wiley, New York, Vols. 1–2

- Suedfeld P 1980 Restricted Environmental Stimulation. Wiley, New York

- Sundstrom E, Bell P A, Busby P L, Asmus C 1996 Environmental psychology 1989–1994. Annual Review of Psychology 47: 485–512

- Ulrich R S 1983 Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In: Altman I, Wohlwill J F (eds.) Human Behavior and Environment. Plenum, New York, Vol. 6, pp. 85–125

- Wicker A W 1979 An Introduction to Ecological Psychology. Brooks Cole, Monterey, CA

- Zube E H, Moore G T, Marans R W 1987–97 Advances in Environment, Behavior, and Design. Plenum, New York, Vols. 1–4