Sample Environmental Change And State Response Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, chech our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Environmental change is one of a myriad of pressures or demands made upon state resources and attention. Many of the responses to environmental stress that occur involve uncoordinated human responses greatly affected by markets. Accordingly, producers and consumers respond to changes in prices, relative incomes, and external constraints. But frequently market ‘signals’ do not reflect social values, as in the case of intergenerational equity, for example, or the deleterious effects of environmental degradation are not internalized in market prices and remain as ‘externalities.’ As a result, states often choose to intervene with collective actions aimed at managing environmental change and reducing the associated adverse social and economic effects.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Accompanying environmental changes will be events and consequences that are potential ‘signals’ of threat to society. Such signals occur with or without societal recognition. If no recognition occurs, there is no (or limited) social learning or stimulation of action by the state, and the lack of response may accelerate the human driving forces of change as a means of positive feedback. If the degradation is recognized, whether by individual farmers, the media, or governmental officials, and elicits recognition and concern, then the response mechanisms of the state are set into action. Once the state receives and recognizes that an environmental change poses a threat, it typically moves to interpret the threat, to assess its social meaning and significance, and to locate it on the policy agenda. Responses occur at many different levels, so scale may become an important factor in state response, particularly ‘scaling-up’ and ‘scaling-down’ problems. These refer to the extent to which patterns and causes of relationships, such as how institutions affect human behavior, observed at one scale can be expected to operate at higher or lower scales (Ostrom 1990, Young 1999). Such issues are only now beginning to receive concerted attention in the social sciences.

All societies, including states, engage in processes by which those at risk, the mass media, societal groups, institutions, and the state itself, assess whether a particular change involves a risk worthy of attention and how serious the risk is. This ‘social processing of risk’ includes information flow; the communication channels and social networks through which individuals, groups, and institutions interact; the formation of public perceptions and concerns; and the degree to which social capital and trust exist. Modern environmental groups play an important role in state response to environmental risk by targeting particular environmental threats for action, in calling such concerns to media attention, and by shaping public values and attitudes. Meanwhile, a global shift in public values has led some analysts (e.g., Inglehart 1990) to highlight the emergence of ‘green ideologies’ related to the growth of ‘postmodern’ values and lifestyle changes with economic development, and the effects of such shifts on heightened public concerns over environmental issues.

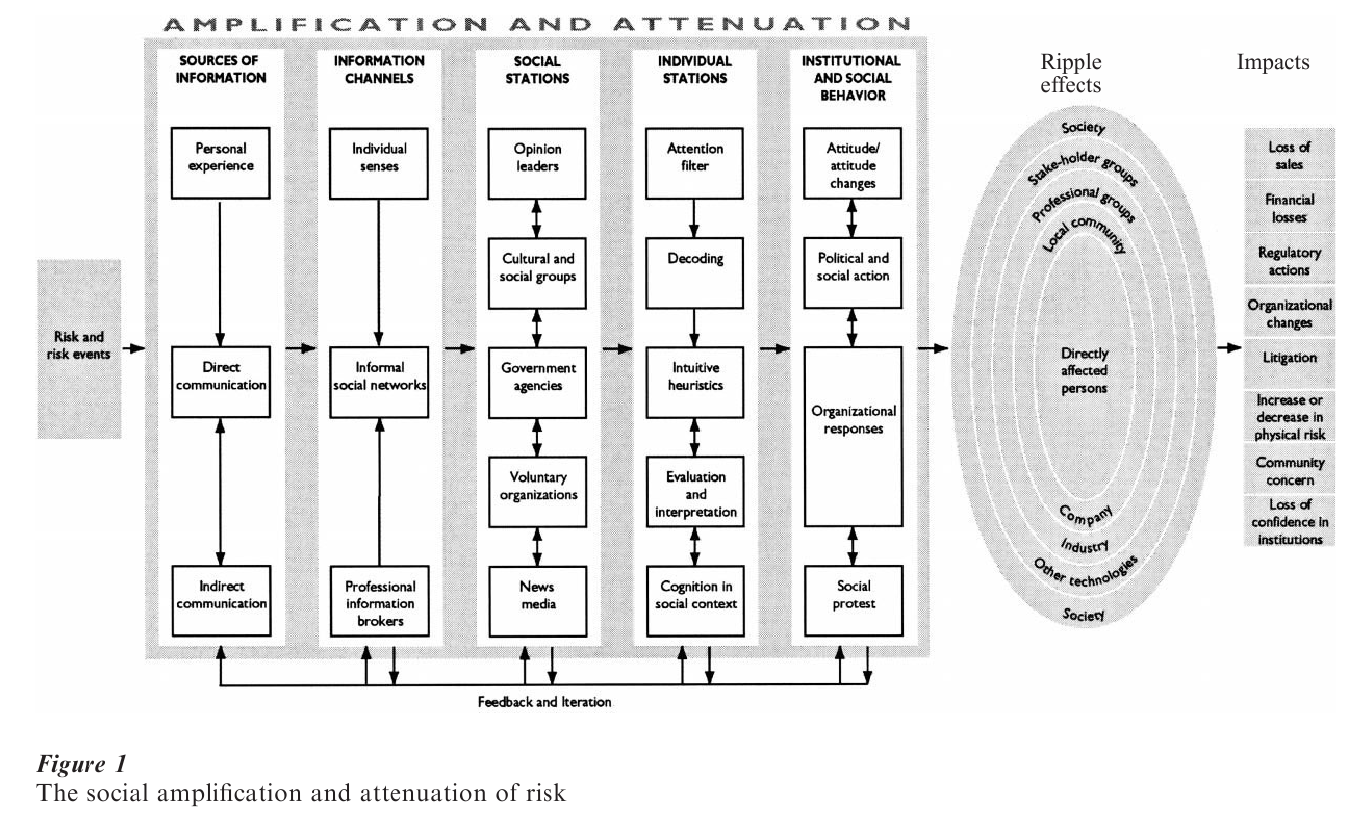

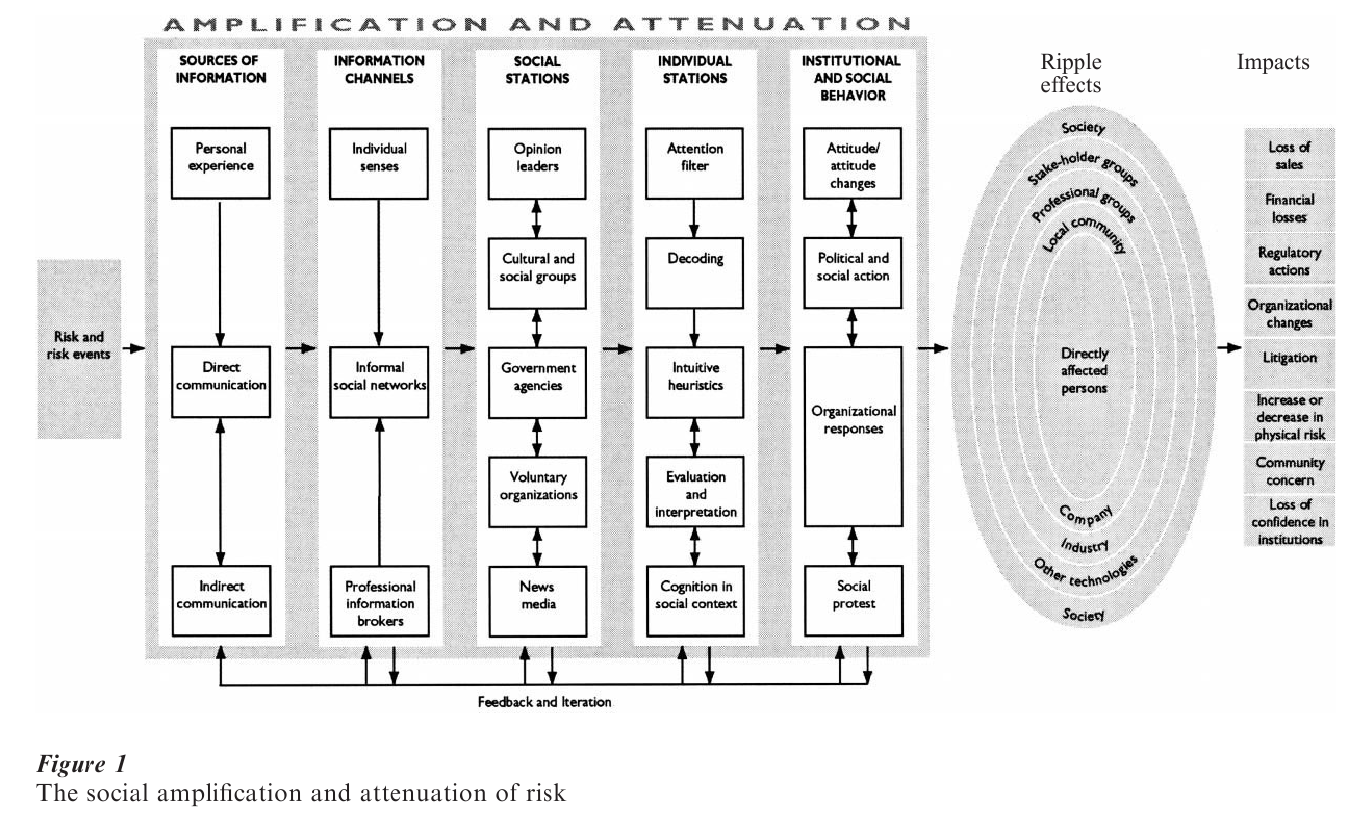

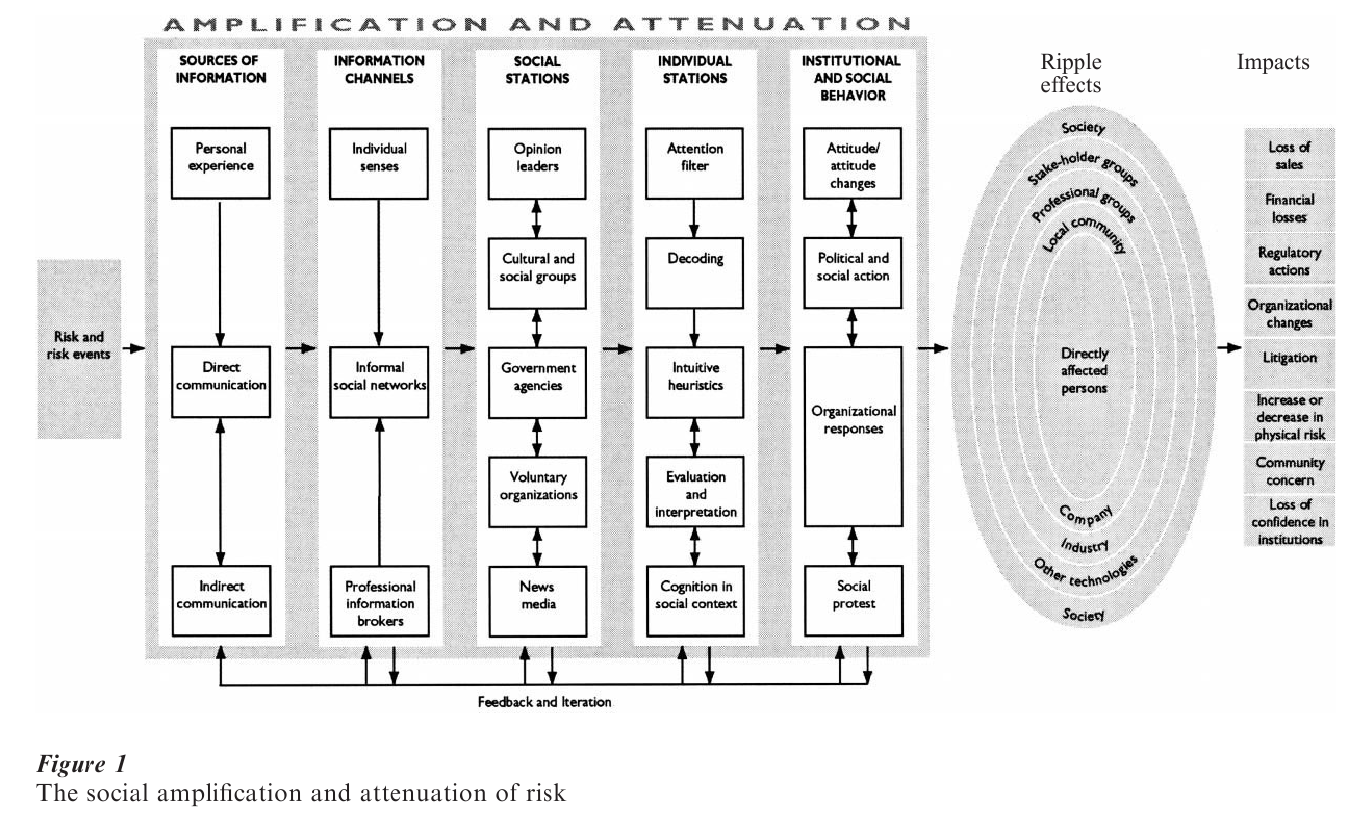

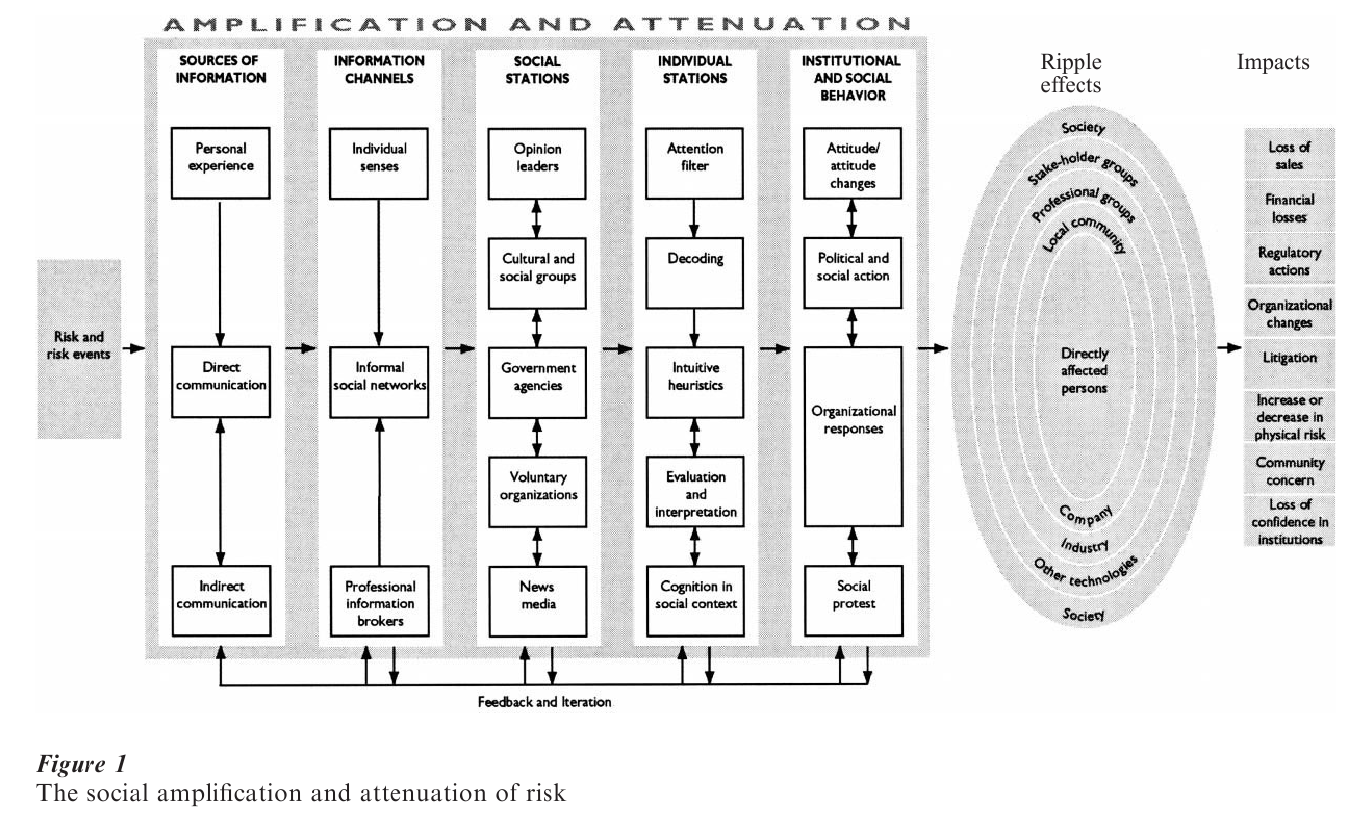

This societal processing function has been described in a ‘social amplification of risk’ framework (Fig. 1), in which social structures and processes ‘amplify’ or ‘attenuate’ signals to society concerning the seriousness and the manageability of the environmental risks (Kasperson et al. 1988). Since most of society learns about the flow of environmental change and risk events through information systems rather than through direct personal experience, risk communicators, and especially the mass media, are major agents (or what are termed ‘social stations’) of risk amplification and attenuation. Particularly important in shaping group and individual views of risk are the extent and content of media coverage, and particularly the way the environmental problem is framed. Information about environmental change flows through multiple communication networks—the mass media represented by television and newsprint, the more specialized media of particular professions and interests (including, increasingly, the Internet or the information superhighway), and, finally, the more informal personal networks of friends and neighbors. The mass media cover risks selectively, emphasizing those that are rare and dramatic while downplaying, or attenuating, more commonplace but often more serious risks, such as soil erosion or climate change. Environmental risks and risk events, thus, compete for scarce space in the media’s coverage, and the outcome of this competition is a major determinant of whether a risk will be socially amplified or attenuated.

In postindustrial states, large organizations— multinational corporations, business associations, and government agencies—mostly set the contexts and terms of society’s debate about environmental problems. The President’s Commission on the Accident at Three Mile Island (1979) in the USA for example, concluded that the ‘mind set’ that permeated the institutions charged with managing nuclear safety represented the primary problem in ensuring the safety of the nuclear technology used to produce electricity. Breakdowns in internal organizational communications can also contribute to attenuation of risk, as occurred in the space shuttle Challenger accident, when the risk concerns of technical experts failed to reach top decision makers within the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Large corporations develop markedly different kinds of organizational cultures that influence their ability to assess the environmental effects of their activities and products. The behavior and interactions of institutions and/or ganizations are major sites of risk amplification and attenuation and require detailed attention in gauging how different countries respond to similar environmental challenges.

Apart from the array of societal processes involved in the social amplification of risk, states also use a variety of means to inform themselves of potential or emerging environmental hazards. Monitoring implies an active and often systematic search by institutions or individuals for information or signals of environmental threats. Alerting refers to the warning function associated with the identification and assessment of risk. Both functions play key roles in identifying social problems and initiating societal responses. The perception of an environmental hazard begins with the first sense of danger but changes as increased information develops. The identification of risks is tied closely to social perceptions and occurs in a variety of arenas within the state—scientific research, the mass media, environmental groups, and the dissemination of industrial products. Global environmental risks, it should be noted, pose new challenges to traditional monitoring and alerting systems. High scientific uncertainty and political stakes are often present in such issues, and past experience is often unreliable as a guide to future risks at the global scale. And so societal alerting and assessment systems assume a larger role and burden in threat anticipation.

State alerting systems for environmental threats range over a wide diversity of institutions, roles, and contexts. Knowledge of environmental change does not always arise from purposeful monitoring of the environment but often occurs by serendipity or by chance. In many cases, the motivation for monitoring is aimed at the realization of some other societal goal, such as health promotion, economic growth and development, or policy effects. Additionally, particular institutions or social groups may experience a change that suggests a departure or discontinuity not previously experienced. Mountain dwellers of Nepal, for example, learn of environmental change through a wide array of experience—increased mudslides, declining crop yields, and growing scarcity of fuelwood, whereas the Nepali government learns about it through accounts of local crises trickling up from remote areas or through reports of failures of development or aid programs (Jodha 1995).

With the initial assessment that an environmental problem exists, it may become a policy issue. How the issue is conceived and socially constructed is critical; political ideology and cultural values are major factors influencing this social construction. The power structure of society directly influences this process, of course, and particular values or ideologies may be dominant in the ‘framing’ of the issue. Authorities of the state, for example, have constructed deforestation in Borneo as a problem of ‘shifting cultivation,’ whereas deforestation and associated fires in Amazonia have been seen as the inevitable price of either frontier development or hamburgers for US markets (Kasperson et al. 1995). If the environmental problem is constructed as a concern only to those most directly involved with the natural resource utilization process (the manager closest to the environmental source), adjustments may be largely cosmetic or of the ‘hidden hand’ variety. If, however, a problem achieves sufficient salience as to require concerted collective action, and comes together with other political confluences needed for policy action, interventions to ameliorate the risk may be undertaken. Whether policy actions or interventions occur will depend upon whether ‘policy windows’ exist, that is, where opportunities for pushing pet proposals or a favored conception of the problem are available (Kingdon 1995). These interventions may be particularly likely at ‘critical junctures’ where three different streams—problems, policies, and politics—which are ordinarily largely independent of one another come together.

Various management strategies are available to state responses, including such options as bearing the risk, preventing or reducing the risk, initiating precautionary actions, spreading or reallocating the risk, fostering greater adaptiveness and resilience, or ameliorating the consequences after they have registered their initial impacts. Among these risk-response strategies, avoidance refers to action to evade the problem or exposure to it (as in relocation from threatened areas); consequence mitigation refers to ameliorating the impacts (as through disaster aid or food relief ); bearing the risk means deciding to absorb the stress and impacts caused by the environmental degradation; risk spreading refers to strategies, such as insurance, that reallocate the risk over larger populations without reducing the risk itself; and adaptation involves strategies by which society changes itself in order to reduce further or future impacts of the risk. Each of these approaches typically makes use of mechanisms appropriate to particular political cultures, such as taxes, regulations, marketable allowances, liability or legal resources, technology-based approaches, social and economic incentives, and dissemination of information (Rayner and Malone 1998). Structural changes—those responses that seek to address directly the basic nature of the driving forces—may also occur but such intervention is more fundamental and politically costly. Technology development, redistribution of land, wealth, and power, and fundamental reorientation of social and economic priorities are examples of such state responses. Still other far-reaching relevant state responses include enhanced status for women, family planning, debt cancellation, land reform, increased support for the traditional rural sector, and inclusion of environmental costs in national accounting systems.

Substantial differences exist among countries in the nature of responses to environmental change. Vogel (1990) argues that environmental concerns in Japan have focused on public health, attention in Germany has centered more on the protection of nature, and the USA and Britain have occupied intermediate positions between Japan and Germany. Variations in national political cultures, the role of nongovernmental organizations, and the power of business in the policy process all contribute to these differences. Different countries also reveal substantial variations in regulatory styles, with the USA displaying an adversarial regulatory style, with demanding and specific quantitative standards, whereas Britain and many other European countries employ more flexible standards and greater discretion in enforcement (Stern et al. 1992).

Global environmental risks may pose distinctive challenges for the state management systems, institutions, and approaches that deal with them. The effectiveness of institutions, it has been argued (Young 1999), depends upon the match between the characteristics of the institutions and the nature of the environmental systems with which they interact. Institutional failures may arise because of mismatches between environmental processes and institutional designs and capabilities. Environmental management often strives for creating relatively high scientific certainty and anticipation, effective ‘rational’ choice among options, and a ‘command-and-control approach to management. Increased attention is being given to ‘adaptive management’ approaches that may be more robust, resilient, and effective over time with many types of transboundary and global risks (Lee 1993). Such a management style proceeds from the recognition that environmental risks often cannot be comprehensively assessed, that large uncertainties typically characterize major elements of the risk problem, and that surprises are certain to occur. Another recent response that has gained favor, particularly in Europe, has been the growing invocation of the precautionary principle as an approach to managing uncertain environmental risks.

Bibliography:

- Inglehart R 1990 Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Jodha N S 1995 The Nepal middle mountains. In: Kasperson J X, Kasperson R E, Turner B L II (eds.) Regions at Risk: Comparisons of Threatened Environments. United Nations University Press, Tokyo, pp. 140–85

- Kasperson J X, Kasperson R E, Turner B L II (eds.) 1995 Regions at Risk: Comparisons of Threatened Environments. United Nations University Press, Tokyo

- Kasperson R E, Renn O, Slovic P, Brown H, Emel J, Goble R L, Kasperson J X, Ratick S J 1988 The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Analysis 8: 177–87

- Kingdon J W 1995 Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, 2nd edn. HarperCollins, New York

- Lee K 1993 Campass and Gyroscope: Integrating Science and Politics for the Environment. Island Press, Washington, DC

- Ostrom E 1990 Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- President’s Commission on the Accident at Three Mile Island 1979 The Need for Change: The Legacy of TMI. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

- Rayner S, Malone E (eds.) 1998 Human Choice and Climate Change, Vol. 4: What Ha e We Learned? Battelle Press, Columbus, OH

- Stern P C, Young O R, Druckman D (eds.) 1992 Global Environmental Change: Understanding the Human Dimensions. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

- Vogel D 1990 National Styles of Regulation: Environmental Policy in Great Britain and the United States. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY

- Young O R 1999 Institutional Dimensions of Global Environmental Change: IDGEC Science Plan. IHDP Report No. 9. International Human Dimensions Programme on Global Environmental Change (IHDP), Bonn, Germany