Sample Second Demographic Transition Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

The term Second Demographic Transition was introduced into demographic literature in the mid-1980s (Lesthaeghe and van de Kaa 1986b; van de Kaa 1987). By then it had become clear that the demographic developments observed in the countries of Northern and Western Europe during the two preceding decades followed a trajectory which would not lead to a new equilibrium between the components of growth as the classical transition theory predicted. It seemed, in-stead, that dramatic changes in family formation and unprecedented low levels of fertility would engender population decline.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. The Components Of Growth

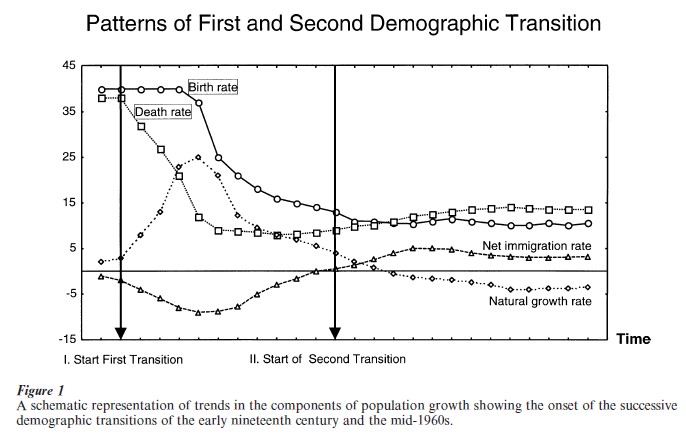

The decline of fertility to below replacement level is an integral part of the Second Demographic Transition, but the second transition does not consist of this fertility decline alone. [JMH: No need to be defensive.] It is constituted by a series of interlinked demographic changes resulting from a quite purposeful shift in behavior by men, women, and couples, a shift that occurred with striking simultaneity in many countries. As was the case during the first transition the demo-graphic changes were the combined effect of structural, cultural, and technological factors. In both transitions changes in value systems played a crucial role (Lesthaeghe and Meekers 1986a). The essential change took place in people’s mind. What one sees is a ‘translation of cultural representations.’ Again, in both transitions the three determinants of population growth moved in conjunction with each other (Cole-man 1996), as follows:

(a) Europe became a region of immigration; the early recruitment of guestworkers may be regarded as the initial manifestation of that new international constellation. It was followed by family reunification, by the inflow of refugees and asylum seekers, and by immigrants seeking to enter illegally.

(b) The decline in mortality, especially at higher ages, and the quite surprising increase in life expectancy during the mid-1970s that resulted, may be interpreted as the lagged response to the behavioral choices men and women made at least a decade earlier. Eating healthier food, giving up smoking, and taking more exercise obviously affect mortality only after a certain delay. National and regional population projections now customarily assume that women will soon experience a life expectancy at birth of 85 years or more.

(c) In the area of nuptiality and fertility, the availability of new, highly effective contraception, commonly followed by increased access to abortion and sterilization, played a catalytic role. Even in the official perception of things, having sexual relations no longer presupposed being married. Male dominated contraception was replaced by means dominated by the female partner. Preventive contraception was replaced by self-fulfilling conception. The changes in fertility and family formation appear to have followed a distinct sequence, partly, no doubt, because of their logical ordering; but also because of the systematic way in which choices were made from available options (van de Kaa 1997).

In the typical pattern, a decline in fertility at the higher ages of childbearing was followed immediately by the avoidance of premarital pregnancies and of ‘forced’ marriages. Initially, the age at first marriage may have continued to decline, but it rose once the postponement of childbearing within marriage became more common. The, lower-order birth rates declined, and cohabitation gained ground. And, while cohabitation may have begun as a statement of defiance by a few trendsetters, and may have remained deviant for a while after that, it increasingly came to be looked upon as an alternative to marriage. Nonmarital fertility rose, voluntary childlessness became increasingly significant, and union disruption became dominated by informal unions rather than marriages.

A common feature was that the postponement of childbirth away from younger ages drove total fertility down to well below replacement level. And, while a compensatory effect may occur through increased childbearing at higher ages, the upper part of the reproductive life span appears insufficient to bring cohort fertility up to replacement level in most countries. [JMH: The Nordic countries appear to be an exception, cf. recent findings by Calot and Tomas Frejka, now in the process of being published.] Ultimately the crude death rate is expected to exceed the crude birth rate. In the absence of international migration, population decline would then become inevitable.

Figure 1 illustrates how the shift from first to second transition appears to have evolved. The sinuous lines of the classical transition pattern are followed by the flat lines of the second. During the second transition the migration process is not expected to develop freely until saturation occurs. Immigration is assumed to remain controlled, but it will compensate only part of the shortfall between births and deaths.

2. Interpretation

This sketch fits the patterns observed in northwestern Europe quite well. An important and interesting question obviously is whether the Second Demo-graphic Transition will prove to be as universal and ubiquitous as the first. Demographers disagree on this point. Some even doubt that the concept of a second transition is appropriate and prefer to see the developments since the mid-1960s as a temporary disturbance in the demographic transition process which began in the nineteenth century (Cliquet 1991, Vishnevsky 1991, Roussel and Chasteland 1997).

Much depends on the interpretation given to the events observed (Lesthaeghe 1995). For a while it seemed as if the second transition could be compared to a cyclone irresistibly sweeping south from Scandinavia and gradually engulfing the South of Europe before turning East and, most probably, to other parts of the developed world. It is now less evident that such a metaphor is appropriate. Three observations should be made to clarify that point. It is, first, obvious that at any point in time each region or country has its own demographic heritage and cultural endowment. The reaction to the diffusion of innovative forms of behavior will depend partly on how well new ideas can be incorporated into existing patterns and traditions.

Since the European countries represent a harlequin’s mantle of experience and conditions, some specificity in reaction is to be expected. Second, It would appear that the Second Demographic Transition has a strong ideational dimension. In the ‘translation’ of cultural preferences and representations into behavior, deeply rooted cultural differences between large regions will make their presence felt. That, so far, southern Europe has not embraced cohabitation as an alternative to marriage and does not show wide acceptance of nonmarital fertility may well reflect a fundamental difference between the ‘protestant’ North and the ‘catholic’ South. It should, third and finally, be recognized that if socioeconomic and political conditions are unfavorable to these novel patterns of behavior, a diffusion process may be much delayed.

This probably partly explains the difference in demographic patterns (trends?) between the previously socialist countries of Eastern and Central Europe and the rest of the developed world. Conceivably, such differences and lags may disappear very rapidly once crisis conditions abate, the economic situation im-proves, and generations exposed to mass culture from the West during their adolescence reach the age at which union formation begins. The Czech Republic has shown extremely rapid shifts in the handful of years between 1992 and 1996, and this may signal developments elsewhere in years to come.

Whether all countries of the world will, ultimately, undergo a Second Demographic Transition is much too early to tell. If Inglehart (1997) is correct in his conclusion that at a certain stage of their social and economic development countries reach an inflection point, and then leave the trajectory of modernization to start moving on the trajectory of postmodernization, a universal second transition is not at all unlikely. He sees postmodernization as a ‘… pervasive change in worldviews.’ ‘It reflects a shift in what people want out of life. It is transforming basic norms governing politics, work, religion, family, and sexual behavior’ (Inglehart 1987, p. 8). Measuring post-modernization (in demographic behavior?) is not particularly easy (van de Kaa 1998).

It essentially implies that at an advanced stage of social and economic development people begin to question the meta-narratives which underpinned the process of modernization for several centuries (e.g., the belief in progress, in the value of working hard, in religion, in obedience to—secular—authority). This means that, just as has been well documented for countries of the European Union after the mid-1960s, concerns about law and order, physical security, and the standard of living give way to higher order needs. The quality of life becomes of prime importance and is placed above material assets in people’s perceptions. People seek personal freedom and gender equality, and emphasize the right to self-realization and self-expression. They express support for emancipatory movements and express concern about the maintenance of human rights, biodiversity, and the ability to sustain modernization style developments (more than even before?).

The probable association of the Second Demographic Transition with long term processes of development in Europe’s societies and/or civilization needs to be researched very rigorously before firm evidence can replace plausible conjectures.

Bibliography:

- Cliquet R L 1991 The Second Demographic Transition: Fact or Fiction? Council of Europe Population Studies No. 23, Strasbourg

- Coleman D (ed.) 1996 Europe’s Population in the 1990s. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Inglehart R 1997 Modernization and Postmodernization. Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Leridon H 1999 Les nouveaux modes de planification de la famille en Europe [The new manner of family planning in Europe]. In: Van de Kaa D J et al. (eds.) European Populations. Unity in Diversity. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht Boston London, pp. 51–77

- Lesthaeghe R 1995 The second demographic transition: An interpretation. In: Mason K O, Jensen A-M (eds.) Gender and Family Change in Industrialized Countries. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 17–62

- Lesthaeghe R, Meekers D 1986a Value changes and the dimensions of familism in the European Community. Euro-pean Journal of Population 2(3–4): 225–68

- Lesthaeghe R, Van de Kaa D J 1986b Twee demografische transities? [Two demographic transitions?]. In: Van de Kaa D J, Lesthaeghe R L (eds.) Bevolking: Krimp en Groei. Van Loghum Slaterus, Deventer, pp. 9–25

- Roussel L, Chasteland J-C 1997 Un demisiecle de demographie dans les pays industriels. Quelques reflections survun bilan [Half a century of demography in industrialized countries. Some reflections on a balance sheet]. In: Chasteland J-C, Roussel L (eds.) Les Contours de la Demographie au Seuil de XXX Siecle. Actes du Colloque International un Demie Siecle de Demographie. Bilan et Perspecti es, 1945–1995. Ined-PUF, Paris, pp. 9–29

- Rychtarikova J 1999 Is Eastern Europe experiencing a second demographic transition? Acta Uni ersitas Carolinae, Geo-graphica 1: 19–44

- Van de Kaa D J 1987 Europe’s Second Demographic Transition. Population Bulletin, 42: 1–57

- Van de Kaa D J 1997 Options and sequences: Europe’s demographic patterns. Journal of the Australian Population Association 14(1): 1–30

- Van de Kaa D J 1998 Postmodern Fertility PBibliography: From Changing Value Orientation to New Behaviour. The Australian National University, Canberra

- Vishnevsky A 1991 Demographic revolution and the future of fertility; a systems approach. In: Lutz W (ed.) Future Demo-graphic Trends in Europe and North America. Academic Press, London, pp. 257–80