Sample Global Population Trends Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

During their evolution of tens of thousands of years, humans have progressively, although not without setbacks, learned how to better feed themselves, make clothing, provide shelter, cure and prevent diseases, improve their health, and modify their fertility. People have learned how to interact in societies which were at first based on gathering, hunting, and fishing. Many societies then experienced the agricultural revolution combined with the domestication of animals. The evolving increases in labor productivity and scientific advancements generated the industrial revolution and urbanization, the foundations of contemporary societies. In the process, populations have grown from very small numbers to the six billion global population reached in 1999. Demographically speaking, for many centuries and millennia changes were erratic and slow until several centuries ago mortality started to decline, life expectancy increased, somewhat later fertility commenced its decline, and populations around the globe began to grow at increasing rates. The more pronounced and rapid changes have occurred in the most recent 100–200 years, although the roots of change reach much further into the past.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. The World’s Population

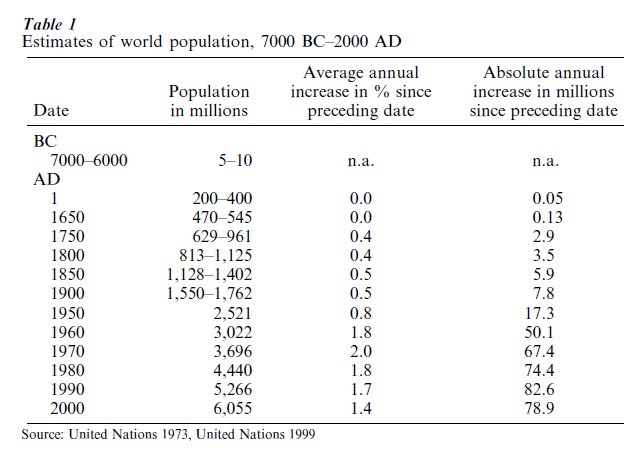

In 1695 Gregory King (1973) was among the first scholars who attempted to estimate the size of the world population. His estimates were within a range of 495–700 million—preferring 630 million as the base for his projections—in line with what scholars engaged in similar exercises since then consider as realistic (Table 1). In 1999, the size of the world population was estimated to have reached six billion inhabitants. ‘Estimated’ because even at the end of the twentieth century uncertainties about the exact size of the world population persist, as there are numerous countries which lack a recent reliable census, and which have inadequate population registration systems or none at all.

Through most of human history the increase in the world population was slow and punctuated by periods of decline. The technologies of food production, as well as the ways and means of health protection, were relatively primitive and humans were thus quite significantly exposed to the vagaries of nature. A notorious case was the epidemic of the plague or Black Death which in the fourteenth century spread from Asia to Europe and Africa and is believed to have decimated Europe’s population by one-third.

The growth of the world population gained momentum in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. However, the critical acceleration occurred after World War II. During the second half of the twentieth century the global growth rate has been close to 2 percent per year. Improved personal health behavior and public health measures as well as the application of curative and preventive medicine which had been attained and practiced in the industrial countries earlier were rapidly spreading in the developing world. It was during this period that the peak and the turning point in global population growth was reached. Since its climax in the1960s with an annual rate of 2.0 percent, this rate has declined to 1.4 percent in the 1990s. In many parts of the world, in developed and developing countries, fertility has been declining rapidly. It is worth noting that the absolute annual additions continued to increase through the end of the twentieth century. They had also reached their peak and were commencing their decline. Around the year 1900 the annual absolute global population increase was about eight million. In the year 2000 it was around 80 million.

Through the end of the twentieth century the number of years required to add an additional one billion population has been decreasing. The first billion was reached around 1804, the second in 1927 (123 years later), the third in 1960 (33 years), the fourth in 1974 (14 years), the fifth in 1987 (13 years), and the sixth in 1999 (12 years). Indications are that this number of years will start to increase in the twenty-first century.

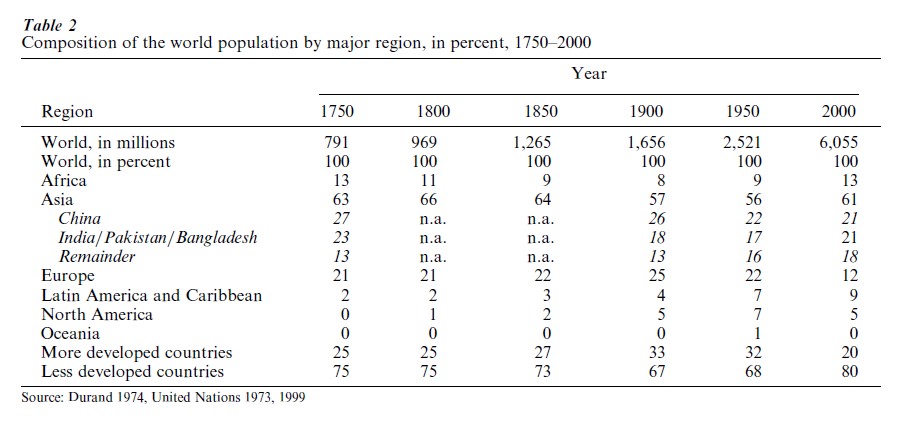

The distribution of the world’s population has been changing over time. For several centuries large populations have been living in China and the Indian subcontinent. In the year 2000 each had about 1.3 billion inhabitants constituting 21 percent of the world population (Table 2).

In the course of the nineteenth century it was the population of the industrial countries in Europe and North America which grew more rapidly than in other regions. Its proportion increased from a quarter of the world’s population to one-third between the beginning and the end of the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, population growth in the developed countries slowed down. Subsequently, during the second half of the century, rapidly declining mortality in Third World countries combined with a fertility decline led to rapid population growth so that their proportion of the world’s population increased from two-thirds around 1950 to 80 percent around the year 2000.

2. Mortality

As best as can be estimated, the average human lifespan in prehistoric and during most of historic times was rather short. The scarce archeological evidence available suggests that most adult deaths occurred between the ages of 20 and 30. In the Iron Age in France average life expectancy was presumably 10–12 years. A life table for ancient Greece, prepared from burial inscriptions, indicates an average life expectancy of 30 years around 400 BC. Life expectancy in Geneva was estimated at about 21 years in the period 1561–1600 and about 26 years in 1601–1700. The latter and other estimates based on fragmentary data in various European countries from the thirteenth to the eighteenth centuries indicate that mortality was very unstable and variable with life expectancy between 20 and 40 years (United Nations 1973). A relatively comprehensive estimate covering Northern and Western Europe, Northern America, and Oceania (The ‘West’) for the middle of the nineteenth century still resulted in an average life expectancy of 40 years. From thereon health conditions improved and life expectancies grew quite steadily in these countries. Elsewhere in Europe and the former Russian empire mortality started to decline later. In Southern Europe, in Italy, for instance, in 1871–80 life expectancy at birth did not exceed 35 years and a steady fall of mortality started after 1875. Japan was another country where mortality was low quite early. Its crude death rate at the end of the nineteenth century was comparable with many European countries.

Malnutrition, poor hygiene, parasitic infections, and disease were, and in many parts of the world still are, the principal causes for high mortality. It took many centuries of gradual progress to have a visible effect on survival. Changes in diet, personal and public hygiene, reinforced by advances in science and medicine, generated dramatic increases in life expectancy. During the past 100–150 years, life expectancy has essentially doubled from 30–40 years to 70–80 years in those societies where most people at the beginning of the twenty-first century enjoy a decent standard of living.

In the Middle Ages most people lived in primitive living quarters with their domesticated animals and their excrements, with an open fire fueled by wood and manure in the middle of the floor and a hole in the roof to let out smoke and cinders, without any toilets and bathrooms, without soap, windows, furniture, dishes, and cutlery. Individual societies around the world were better equipped in some respects, for instance, the Chinese employed coal as a fuel, and soap was commonly used in the Islamic world. Frequent failures of harvests and major epidemics were commonplace everywhere. It took many centuries for standards of living and hygiene to improve and thus provide favorable conditions for better health. Residential chimneys in Europe became common around 1200 and it was Marco Polo who discovered in 1306 that the Chinese used coal to heat their homes. Soap was manufactured for the first time in London presumably in 1259. Frequent bathing, however, was considered unhealthy and as late as in the sixteenth century Queen Elizabeth I was considered eccentric for her frequent bathing—once a month. It was not until the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that the way people lived changed considerably and irrevocably. Significant increases in productivity, including agriculture, provided for the possibility of improved nutrition, shelter, and living conditions in general. In combination with the gradually increasing application of personal hygiene, the installation of indoor plumbing and introduction of sewage systems, the accumulation of scientific and medical knowledge as well as the spread of health services networks, this all led to the gradual improvements in health and the decline of mortality.

The profound long-term changes in patterns of death, disease, and disability have been labeled the epidemiological transition (see Omran 1971). It has three courses of change: a shift from infectious and parasitic to chronic and degenerative diseases, a shift in the burden of death and disease from the younger to the older population, and a shift from a health picture dominated by mortality to one dominated by morbidity. In general, these directions of change occurred in the developed countries before the middle of the twentieth century. In developing countries, during the latter part of the twentieth century, often the increase in chronic and degenerative diseases coexisted with relatively high levels of infectious diseases (Bobadilla et al. 1993). Most of the morbidity of contemporary advanced societies is preventable because in large part it is due to ills and imperfections of social and individual behavior. It is due to undesirable side effects of industrialization, urbanization, and mass consumption such as atmospheric pollution, environmental degradation, accidents, mental tension and distress, consumption of tobacco, alcohol and drugs, unhealthy diets and obesity (Jozan 1998). Efforts to control and reduce this morbidity are underway, but results are mixed. The complexities are numerous. Consequently, there are large differences regarding success and failure in lowering mortality and morbidity between countries, within countries among regions and social strata.

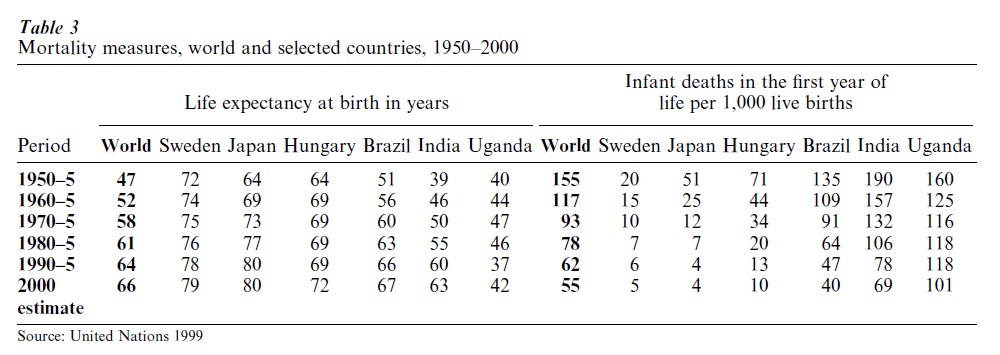

The progress and problems of mortality and morbidity change in the past 50 years are illustrated by data in Table 3. In most countries around the world major improvements were achieved during the second half of the twentieth century. Nonetheless, there were two types of exceptions. Hungary exemplifies the stagnation in mortality decline of the formerly socialist countries of central and eastern Europe and Uganda represents the countries of sub-Saharan Africa where mortality declines were reversed mainly as a result of the HIV AIDS epidemic. At the same time, significant improvements in the health conditions of infants have been achieved around the globe, but major differentials persisted through the end of the twentieth century (United Nations 1999).

3. Fertility

In the long run, additions of births have to at least match attrition by death if a society is to survive and perpetuate. That is what has been happening throughout humanity’s history and before. Fertility could not decline from traditional levels prior to any significant decline of mortality without causing the extinction of human populations.

As long as mortality was high and a large proportion of infants, children, and adolescents died before entering their reproductive ages, women would bear on average 5–8 children. Such high fertility is persisting at present in a number of countries with high mortality, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. There are, however, only few such countries remaining. For the most part, fertility has either already declined to very low levels or countries are on their way between high and low fertility.

The biological maximum a woman can bear during her childbearing period is between 13 and 17 children. As a rule, this does not happen as there are numerous deliberate/conscious as well as unintended/unconscious mechanisms limiting births. Until the nineteenth century in the advanced countries, and until only several decades ago elsewhere, breast-feeding— occasionally combined with taboos in intercourse during lactation—was the decisive factor bringing down the number of children born to between 5 and 8. In premodern times almost exclusive breast-feeding tended to be the rule for infants and for many children at times until they reached their second or even third birthday. For most women this practice prevented a further pregnancy. An extreme example are the San of the Kalahari Desert who were not subject to any taboo and yet they achieved four-year birth intervals through the contraceptive effect of frequent (four times an hour) breast-feeds. The physiological process taking place is such that when the baby suckles on the nipple, nervous impulses pass from the breast to the brain to inhibit the release of hormones responsible for ovulation from the pituitary gland (see Potts and Short 1999).

Women breastfeed as it is the most natural and convenient way to feed infants, at the same time the conception preventing effect was apparently known for millennia and in some societies widely realized. Aristotle stated in the Generation of Animals that ‘while women are suckling children, menstruation does not occur according to nature, nor do they conceive.’ In 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft wrote in the Vindication of the Rights of Women: ‘Nature has so wisely ordered things that did women suckle their children, they would preserve their own health, and there would be such an interval between the birth of each child, that we should seldom see a houseful of babies.’ Lactation has other critical salutary effects. Maternal milk is the most beneficial source of nutrition finely adjusted to the needs of the offspring. It is also a living secretion, rich in antibodies that protect against disease. Therefore, particularly in developing countries, breastfed babies tend to be healthier than their bottle-fed peers.

Other critical factors reducing fertility are delayed cohabitation of partners marriage, the use of contraceptives, and the prevalence of induced abortions. Prior to the latter part of the nineteenth century, these were known, however, they were not widely practiced and therefore they were not decisive in modifying fertility. Western European marriage patterns were the exception. Hajnal (1965) observed that since the eighteenth century fertility had been relatively low and at times declining in countries west of a line between St. Petersburg and Trieste precisely because the age of marriage was high. Later, the considerable fertility decline in western countries in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was apparently brought about by the application of relatively unsafe induced abortions as well as the use of traditional methods of contraception, such as coitus interruptus (Santow 1995). There is, however, scarce statistical hard evidence to support this statement.

During the second half of the twentieth century safe induced abortions became increasingly available for a large proportion of the world population and unsafe abortions were widely practiced in Latin America and Africa. A ‘contraceptive revolution’ was underway throughout the developed countries and increasingly in the developing ones as well. In most countries the use of contraceptives increased, modern contraceptives such as the IUDs and oral contraceptives found extensive application, and female as well as male contraceptive sterilization was widely adopted, although differences between countries were considerable. The prevalence of contraceptive use rose to between 70 and 80 percent of married women in the developed countries, and in countries such as Taiwan and South Korea, the use of contraceptives increased from 20 to 80 percent within a period of about three decades (see Frejka and Ross 2001).

Relatively late marriage, the use of contraception, and induced abortion are the means of modifying fertility. The motivations and decisions to regulate fertility, subconscious or conscious, have numerous economic, social, cultural, and political roots. The following developments are critical. With economic progress children have evolved from being an asset to their parents to become a costly investment. Growing proportions of young women and men remained in school or found employment outside the household and therefore entered marital or consensual unions later than their parents. The family, particularly the younger generation, used to take care of older members of the household; increasingly older people have to take care of themselves possibly assisted by the state. As recently as in the nineteenth century women everywhere were oppressed and disadvantaged, nowhere did they have the right to vote, for instance. In various parts of the world many women are still battered, sequestered, mutilated, or exploited, but a basic trend supporting their empowerment is in progress. Thus, increases in women’s education and employment, their earning potential in the marketplace, and growing equality vis-a-vis laws have enabled women to partake in decisions regarding fertility behavior.

Population policies—deliberate interventions to influence a population development—have frequently been formulated and employed by governments or international institutions. With respect to fertility, governments perceiving it to be too low may devise policies which they believe will raise fertility; those regarding high fertility as a burden implement measures to diminish it. Berelson (1977), for instance, demonstrated that there are numerous policies which may conceivably reduce fertility. He clarified how policy makers taking local circumstances into account should and usually do consider whether the policies they wish to employ are acceptable to the political elite and to the public, whether they are feasible with given resources and administrative infrastructures, and how effective they will be.

Particular social, economic, political, cultural, and religious circumstances sometimes in combination with population policies shape people’s fertility desires, motivations, and behavior which is expressed in their marriage patterns, breast-feeding practices, contraceptive use, and prevalence of induced abortion and thus result in a certain level and trends of fertility.

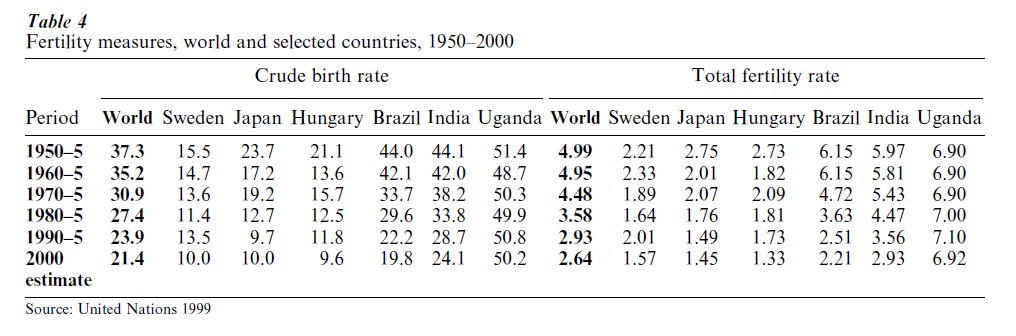

The unprecedented changes in fertility which occurred during the second half of the twentieth century are illustrated in Table 4. The total fertility rate, a measure which can be interpreted as the average number of children borne by a woman, on a worldwide scale declined from about five children in the early 1950s to just over two-and-a-half in the year 2000. In the developed countries, represented by Sweden, Japan, and Hungary, fertility declined from an already low level in the early 1950s to significantly below the replacement level of about 2.1 children per woman. The decline was not linear, some fluctuations did occur, however, at the end of the twentieth century not much less than half the world’s population lives in countries with below replacement fertility (see Frejka and Ross 2001). In developing countries around 1950, fertility was high, between six and seven children per woman. In a significant number of countries it declined close to the replacement level, such as in Brazil. In others like in India fertility was considerably reduced. In some countries, however, no discernible change took place. Uganda is typical of sub-Saharan countries with stable high fertility, although there are some where a decline has commenced.

Even though there has been a considerable fertility decline in most developing countries in the past several decades, continued population growth can be expected and will be forthcoming during the first half of the twenty-first century. Past high fertility has produced large cohorts of young people who are presently in the childbearing stage of their life cycle or who will enter their childbearing years. Even if these generations will have low fertility, the total numbers added to the populations of the developing countries are almost sure to be much larger than the number of people dying.

4. Concerns

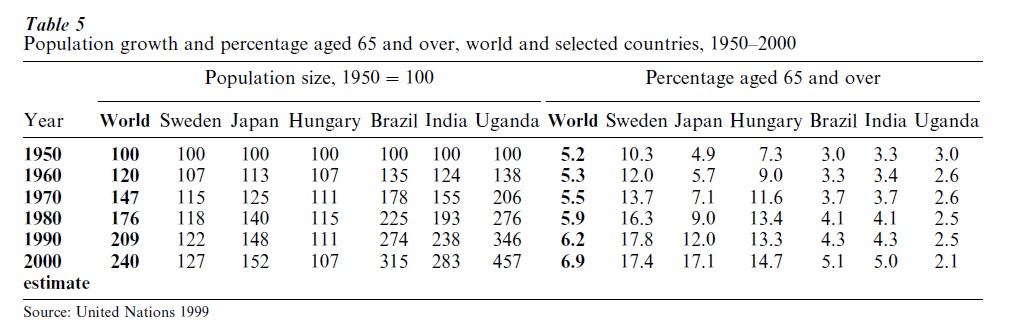

Table 5 illustrates basic demographic developments which are frequently causes for concern among policy makers, scientists, and the general public. The world population has grown more rapidly during the second half of the twentieth century than ever before. Rapid population growth, even though at a moderating pace, will continue for some decades. Extraordinarily fast population growth has occurred in developing countries. Brazil’s and India’s populations, for instance, have grown threefold, Uganda’s 4.5 times. Such growth creates obvious dilemmas and pressures for governments, the private sector, and international organizations striving to raise educational levels, improve health conditions, broaden employment opportunities, and elevate living standards in general. Population growth coupled with increasing consumption in developed and developing countries increases dangers of specific resource depletions, environmental degradation, selective plant and animal extinction, which ultimately could pose problems for and harm the human species. Concern is also voiced that rapid population growth can be a factor exacerbating poverty and political instability.

Hungarian population change exemplifies a shrinking population. There were more than 10 such nations in Europe in the late 1990s and thus concerns for a diminishing labor force, declining international stature, the potential of dying out as a nation, and others have surfaced.

Rapidly declining and low fertility gives rise to changes in the age structure and together with increasing longevity are the root causes of population aging. In the late 1990s in many developed countries 15 percent or more of populations were of age 65 and over. The numbers and proportions of the elderly have been increasing and there is no doubt that they are going to continue to do so. This is one of the major concerns of governments in the developed countries because considerable state expenditures go toward social security benefits of the elderly as well as their health care. As fertility is declining rapidly in many developing countries, population aging is becoming an important social and political issue.

Bibliography:

- Berelson B 1977 Paths to fertility reduction: The ‘policy cube.’ Family Planning Perspectives 9(5): 214–19

- Bobadilla J L, Frenk J, Lozano R, Frejka T, Stern C 1993 The epidemiologic transition and health priorities. In: Jamison D T, Mosley W H, Measham A R, Bobadilla J L (eds.) Disease Control Priorities in De eloping Countries. Oxford Medical Publications, Oxford, UK

- Chesnais J-C 1992 The Demographic Transition: Stages, Patterns, and Economic Implications. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Coale A J 1974 The history of human population. Scientific American 231(3): 40–51

- Cohen J E 1995 How Many People Can the Earth Support? W W Norton, New York

- Durand J D 1974 Historical Estimates of World Population: An Evaluation. Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania, PA

- Frejka T J, Ross A 2001 Paths to subreplacement fertility: The empirical evidence. In: Bulatao RA, Casterline JB (eds.) The Global Fertility Transition, Supplement to Population and Development Review 27

- Jozan P 1998 Some features of mortality in the Member States of the ECE. In: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, Background Papers of the Regional Population Meeting, December 1998 (unpublished)

- King G 1973 17th century manuscript book of Gregory King. In: Laslett P (ed.) The Earliest Classics: Graunt and King. Gregg, Farnborough, UK

- Omran A 1971 The epidemiologic transition: A theory of the epidemiology of population change. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 49: 509–38

- Potts M, Short R 1999 Ever Since Adam and Eve: The Evolution of Human Sexuality. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Santow G 1995 Coitus interruptus and the control of natural fertility. Population Studies 49(1): 19–43

- United Nations 1973 The Determinants and Consequences of Population Trends. United Nations, New York, Vol. 1

- United Nations 1999 World Population Prospects: The 1998 Revision. United Nations, New York

- Wollstonecraft M 1985 [1792] Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Penguin, London