Sample Population Aging Consequences Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

The notion of aging is quite natural for human beings: from the age of reason, we understand that with the passage of time, every living thing ages and finally dies. Young children experience this with their goldfish or dog, adults with their parents and old people with their friends. By analogy, we apply the notion of aging even to nonliving things: for example, as a car deteriorates, we say that it is getting old and eventually we relegate it to the scrap lot. Although a good wine may improve with age, in the end it becomes undrinkable.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

From the individual, the notion of aging is extended to the group formed by the individuals: thus we speak of an aging fleet of cars or an aging population, meaning that the average length of life of the entire group of these individual units changes with the passage of time. However, unlike the case for the individuals making up the group, the group itself is able not to age, or even to get younger. This is the case for human populations. For them the aging process is strictly structural, not biological. The decay generally associated with the aging of individuals should not be assumed to apply to aging populations.

1. Population Aging: A Modern Demographic Phenomenon

A population changes through the interaction of the fertility, mortality, and migration of its members. In recent centuries, we have witnessed remarkable changes in human fertility and mortality, which, uncontrolled since time immemorial, had always been high. In the past, there was a ‘natural’ fertility and mortality, and population numbers throughout the world were relatively low. Eventually, people found ways to reduce first mortality and then fertility after a certain time lag. In theoretical terms, this historical process is known as the demographic transition (Chesnais 1986). During this process, the population grows at a higher or lower rate, depending on the extent of this time lag. At the end of the process, according to the theory, both fertility and mortality are low and the population stops growing. But an inescapable law of demography says that a population either grows or it ages (Coale 1987). As all populations around the world have reduced or stopped their growth, they are all bound to age. In some countries the fertility level is well below the replacement level, and thus their populations will decrease unless they experience in-migration, a possibility not foreseen by classical transition theory.

There are several ways of measuring the aging of a population. Instinctively, one could say that a population is aging if the average—or median—age of its members as a group increases over time. Alternatively, one could look for an increase in the proportion of old people in the population. But at what age does a person become old? We do not want to enter into a debate over the exact threshold of old age or retirement, but for purposes of illustration we will use the percentage aged 65 and over in the population . To avoid delving too far into the past or future, we will restrict our discussion of demographic aging to the period from 1950 to 2050.

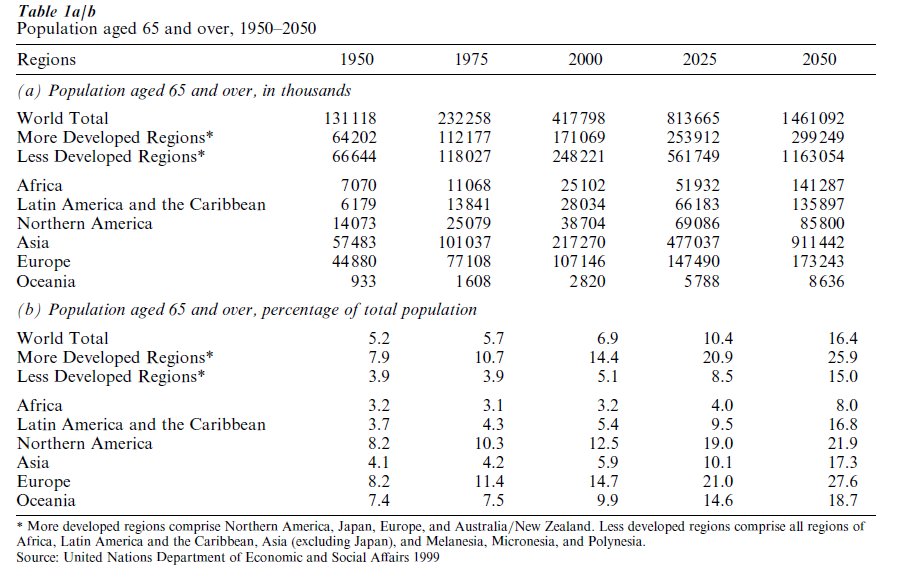

During the twentieth century, the growth in the number of people aged 65 and over was relatively small and there were roughly as many people old (according to this definition) in industrialized countries as in less developed countries. However, from now until 2050, this number will grow spectacularly, mainly because of the increase in less developed countries (Table 1a). But if we look at the proportion of people aged 65 and over in the population, as a measure of demographic aging between 1950 and 2050 (Table 1b), we see that the situation differs greatly from one continent to another. Africa will remain young while the more developed countries as a whole will have more than one-quarter of their populations in the ‘old’ category. Asia will age at an increasing rate: in 2050, it will have more than 900 million people aged 65 and over. This is two-thirds of the world’s elderly population.

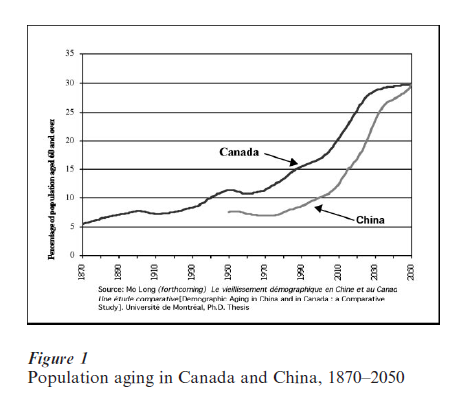

In the industrialized countries, the process of population aging is relatively slow, but in developing countries it will be more intense and rapid. This can be clearly shown by a comparison of Canada and China (Fig. 1). In 2050, China will be a world leader in demographic aging with almost 450 million people aged 60 and over. This is close to 30 percent of its total population.

In the face of globalization, the changes occurring over this century will give rise to a number of socioeconomic issues that would not have made themselves felt if population aging affected only the currently industrialized countries. There will be both demographic and economic and social consequences for our societies.

2. Demographic Consequences

As is easily demonstrated, in the early stages of the demographic transition aging is much more the result of a decline in fertility than in mortality. When mortality declines from a high level, it is primarily early deaths that are eliminated, in particular deaths of children and young adults. The result is a younger (not older) population, as was seen in Africa in the 1950s and 1960s (Table 1b).

But when life expectancy is already very high, as is the case now in industrialized countries, mortality becomes an important factor in demographic aging. If mortality is low and decreasing, we get a double effect. First, increasing numbers of people reach the old age threshold—because of lowered mortality before that age. Second, people live for increasing lengths of time beyond this threshold—owing to a continued decline of mortality at old age (Bourbeau et al. 1997). The main consequence of this development is that old people no longer form a homogenous group: we now have the young old, who generally are in quite good health, and the oldest old, who generally are more dependent for income security and health. Thus we have moved from having three main lifecycle stages to four. There is a new third age that extends from retirement to the oldest-old stage. This is an entity that never existed before in human history (Laslett 1989). Another important feature in mortality changes in many societies has been an increased mortality gap between men and women. Very frequently old people in these societies are and will continue to be primarily old women.

Like any other population, the elderly population is subject to a process of incessant inward and outward movement of cohorts. In most industrialized countries the incoming generations will be clearly differentiated with respect to their numbers and their characteristics. The generations now approaching retirement are the Baby Boomers born after World War II. They will be followed by the Baby Busters, who are far less numerous. These generations, particularly the women, will have characteristics very different from those of today’s old people (Marcil-Gratton and Legare 1987), especially in terms of education.

The changes in the age structure of our societies will cause major realignments that affect not only the elderly but the entire population. In terms of health and financial security, will old people be more independent or more dependent than before? The increasing presence of very old people tends to suggest dependence, while the characteristics of the future younger elderly appear to suggest greater autonomy. Will the younger adults, who are far less numerous than the Baby Boomers, be willing to pay for a golden twilight for tomorrow’s seniors? We now turn to these questions in the following sections.

3. Economic Consequences

3.1 The Aging Process And The Working-Age Population

At the beginning of the population aging process, a standard age pyramid shows the population cohorts by age increasingly reduced by mortality. As the process gradually proceeds, positive impacts on the working-age population appear. The decline in mortality eliminates early deaths and increases population numbers. Then, as the effects of fertility decline come to the fore, cohort size is increasingly reduced. When mortality improvements lead to significant reductions in old-age deaths, the members of the retired cohorts become as numerous as, and sometimes more numerous than, those of working-age cohorts. The pyramid changes into a top and finally into a cylinder. This means that at the end of the aging process, all generations are of approximately the same size except for the very old. This process is reflected in the variations of what are commonly called the dependency ratios, one of which is the ratio of people aged 65 and over to those aged 19–64. Unfortunately, the use of the adjective ‘dependency’ may unduly give an impression of economic dependence. These indicators are merely indices of the age structure and it would be more appropriate to speak of demographic dependency ratios.

In studies of aging we frequently find the members of the working-age population equated to actual workers. While in the past this was true for men when their labor force participation rate was close to 100 percent, it is now less so, in particular for women. To assess the economic impacts of aging and our ways of dealing with them, we needed to take into account not only population numbers, but perhaps more importantly labor force participation rates and worker productivity (Fellegi 1988). If the shift from agricultural to industrial societies had great impacts on the world of work, the shift to aging post-industrial societies will have an equally great impact. This is particularly true for the change in the rate of labor force participation by women and by older workers.

The radical decline in fertility and otherwise changing family arrangements has freed women from a myriad of family duties and made them available for increased participation in the paid labor market. The women’s liberation movement also contributed to changes in attitudes and women are becoming increasingly independent, not only at working age, but also, and perhaps especially, during retirement.

One of the corollaries—and achievements—of the development of industrial societies has been the right to retirement and associated pensions. In this century we have witnessed a decline in the labor force participation rate of older workers, along with a systematic decline in the age of leaving the labor market. This ever-earlier retirement from the labor market is now increasingly being questioned. As life expectancy increases, especially at old age, and as the time spent taking education is extended, the life segment in retirement is growing longer and the segment in which one works is getting shorter. When a large and growing share of the costs of social security, including pensions and health insurance, is borne by those who work, some adjustments must be considered. It is not possible to maintain contribution and benefit levels and, simultaneously, to bring down, or even maintain, the age of access to benefits.

There is a need for greater flexibility, both in wages and responsibilities for the population approaching retirement. For older workers, one should consider a gradual progression from wages to pension income, perhaps following a normal rather than S-shaped curve. This may call for a change in attitudes, not only among the workers themselves but also among employers and trade unions.

Solidarity among generations presupposes a minimum of equity between groups. When social security programs in the industrialized countries were reorganized after World War II, both the population and the economy were growing: the populations were young. Pay-as-you-go financing did not create any visible problems and it eliminated some perverse effects of funded programs, many of which had collapsed in Europe during the Depression and the war. In aging societies—particularly those which have experienced a large baby boom followed by a baby bust—a hybrid system combining pay-as-you-go and funded elements is likely to be more equitable across generations.

At present, the labor market is undergoing major changes. Workers will no longer hold full-time jobs for life the way they did previously in industrial societies. New workers will enter the labor market later in life. They will hold part-time jobs with varying employers, more often and possibly for a significant part of their working life, or be self-employed. From time to time they will have periods of unemployment or of retraining. Moreover, such patterns, which formerly applied mainly to women, will now apply to men as well. Consequently, retirement systems based on previous labor market participation and involving individual employers will be subject to in-depth revision. In addition, one should take the value of unpaid work into account. In particular, work performed to raise children or to care for aging parents needs to be recognized.

3.2 An Aging Society: A Burden?

Because population aging is equated to individual aging all too often, one tends to highlight problems for aging societies, in particular problems related to the costs of health and pension programs for the elderly. On this subject some issues need to be clarified and some myths should be dispelled.

First, the situation of old people in most countries has improved greatly largely as a result of post-war social programs. There have even been hard economic times when their situation has deteriorated less than that of younger people.

Second, health and pension costs will certainly continue to increase in aging societies, but at what rate will this happen? With regard to health Zweifel et al. (1999) have shown that increases in medical costs are more closely linked to the number of old-age deaths than to the size of the elderly population, and the number of old-age deaths is increasing much less rapidly than the size of the elderly population. The same is not true for pensions, whose costs are linked directly to the number of old people. However, one should not forget that retired people also pay taxes, both on their income and on consumption. As people age, their material needs (other than those related to health) decrease, however, and this might be reflected in their pension requirements.

Third, although incomes are on average lower at old age than at other ages, the elderly often hold a large share of the collective wealth through their assets, in particular by owning of their dwellings.

In brief, far from being an impediment to economic development, elderly people in aging societies can sometimes serve as an important actor if not the engine of such development.

4. Social Consequences

Increasingly, the group of old people is not homogeneous with regard to health status and wealth, and this has numerous consequences for their life-style. First, let us recall that to a large extent the world of the elderly is a world of old widows. This feature has become increasingly prominent over the twentieth century, as excess male mortality has grown while the difference in age at marriage has remained stable. In addition, this century has been characterized by the quest for greater independence at all ages. Old people in industrialized countries prefer to live alone if they do not live with their spouse, particularly when they are in good health. But this choice does not necessarily imply isolation. Alternatively, living together with people other than one’s late spouse may become a strategy for dealing with financial or health problems, perhaps as a stage that precedes institutionalization.

Multigenerational households are much more common in less industrialized countries, mainly for cultural and economic reasons. We can only wonder what will happen in the future in these societies. In a context of rapid urbanization and scarcity of dwellings, there will be an acceleration in aging following the sharp decline in fertility. With its one-child policy, China is a particularly poignant case. Demographic constraints may become apparent as daughters and daughters-in-law become increasingly less numerous and less often available to take care of old parents.

In societies with low mortality (or equivalently, long life expectancy), early deaths are reduced to a minimum and are usually related to life-style rather than caused by exogenous diseases. This produces a great deal of interest in the population’s health status, and public health policy objectives may concentrate on insuring quality of life for the aging population more than on preventing early adult deaths. The focus moves from mortality to morbidity, from life expectancy to healthy-life expectancy (Robine and Romieu 1998). By means such as surveys on seniors’ functional capacities, it is possible to identify impediments to independent existence and to develop policies that will minimize the adverse effects of biological and social aging.

Such policies are centered on support networks. Assistance provided to old people may come from professionals hired by the state, the community, or private enterprise. Alternatively, they may be offered by the family, friends, or neighbors. The expanding need for services provided through such formal and informal networks is an increasing source of concern. For the informal networks, the many changes that have occurred in family structures leave future prospects unclear; for the formal networks, it is mainly the cost that worries public policy makers. In this picture one should not forget that seniors are not only receivers of assistance, but very often also providers.

5. Conclusion

Some believe that the twenty-first century will see the emergence of intergenerational conflicts similar to the gender conflicts of the twentieth century. Major transformations of the population age structure have altered the ratio between the retired and the working population and will continue to do so. In addition to solidarity among generations, any reforms to social security programs taking account of the new demographic reality need to aim to promote intergenerational equity. For this purpose, we have seen the development of new measurement techniques, known as demographic accounting (Auerbach et al. 1999). By making use of individual-level data and by making adequate long-term projections we will be able to benefit from these new methodologies.

In conclusion, we observe that for centuries, life in all its forms was regulated by nature. Gradually, human societies became able to control their destiny by largely controlling their mortality and fertility. This resulted in great changes for the societies, and in particular it accelerated their aging. The fact that most now live to old age and that our populations progressively age can only be regarded as great cultural progress (Loriaux et al. 1990). However, like all progress, individual and societal aging must be managed skillfully. Moreover, we are in the midst of a process of shifting control from society to the citizen (Legare and Marcil-Gratton 1990). Decisions concerning demographic behavior, like whether or not to get married, whether to have children, how many and when, whether to leave an existing marriage and contract another one, and so on, are now made on the individual level more than ever before. In a world where centenarians will become rather common, people will doubtless also want to have a say on the timing of their departure from life.

Bibliography:

- Auerbach A J, Kotlikoff L J, Leibfritz W (eds.) 1999 Generational Accounting around the World. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Bourbeau R, Legare J, Emond V 1997 New Birth Cohort Life Tables for Canada and Quebec, 1801–1991. Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Canada

- Chesnais J C 1986 La transition demographique: etapes, formes, implications economiques: etude de series temporelles (1720–1984) relatives a 67 pays. Presses universitaires de France, Paris [1992 The Demographic Transition: Stages, Patterns, and Economic Implications. Oxford University Press, New York]

- Cliquet R, Nizamuddin M (eds.) 1999 Population Ageing. Challenges for Policies and Programmes in De eloped and De eloping Countries. United Nations Population Fund, New York

- Coale A 1987 How a population ages or grows younger. In: Menard S W, Moen E W (eds.) Perspectives on Population: An Introduction to Concepts and Issues. Oxford University Press, New York

- Fellegi I P 1988 Can we afford an aging society? Canadian Economic Observer 1,10: 4.1–4.34

- Laslett P 1989 A Fresh Map of Life. The Emergence of the Third Age. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London

- Legare J, Marcil-Gratton N 1990 Individual programming of life events: A challenge for demographers in the 21st century. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 610: 98–105

- Loriaux M, Remy D, Vilquin E (eds.) 1990 Populations agees et revolution grise: les hommes et les societes face a leurs veillissements [Aged Populations and Grey Revolution: Humans and Societies Facing their own Ageing]. CIACO, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium

- Marcil-Gratton N, Legare J 1987 Being old today and tomorrow: A different proposition. Canadian Studies in Population 14,2: 237–41

- Martin L G, Preston S H (eds.) 1994 Demography of Ageing. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

- Mo Long (forthcoming) Le vieillissement demographique en Chine et au Canada: une etude comparative [Demographic Aging in China and in Canada: a Comparative Study]. Ph.D. thesis, Universite de Montreal

- Murray C J L, Lopez A D (eds.) 1996 The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020 (on behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank). Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 1988 Ageing Populations. The Social Policy Implications. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Paris

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 1998 Maintaining Prosperity in an Ageing Society. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Paris

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 2000 Reforms for an Ageing Society. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Paris

- Robine J M, Romieu I 1998 Healthy Active Ageing: Health Expectancies at Age 65 in the Different Parts of the World. REVES INSERM, Montpellier, France

- Stolnitz G J (ed.) 1992 Demographic Causes and Economic Consequences of Population Ageing: Europe and North America. UN Economic Commission for Europe (ECE), Geneva, Switzerland

- Stolnitz G J (ed.) 1994 Social Aspects and Country Reviews of Population Ageing. UN Economic Commission for Europe (ECE), Geneva, Switzerland

- Suzman R, Willis D P, Manton K G 1992 The Oldest Old. Oxford University Press, New York

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs 1956 The Ageing of Populations and Its Economic and Social Implications. United Nations, New York

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs 1988 Economic and Social Implications of Population Ageing. United Nations, New York

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs 1999 World Population Prospects: The 1998 Revision. United Nations, New York

- World Bank 1994 Averting the Old Age Crisis: Policies to Protect the Old and Promote Growth. Oxford University Press, New York

- Zweifel P, Felder S, Meiers M 1999 Ageing of population and health care expenditure: A red herring? Health Economics 8,6: 485–98