Sample Human Ecology and Demographics Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

1. Introduction

Human ecology is the ‘the study of the form and the development of the community in human populations’ (Hawley 1950, p. 68, Hawley 1971) for which the unit of analysis ‘is not the individual but the aggregate which is either organized or in the process of being organized’ (Hawley 1950, p. 67) and where the concept of ‘community’ is defined as a ‘territorially based system of functional interdependencies that results from the collective adaptation of a population to its environment’ (Berry and Kasarda 1977, p. 12). Human ecology proposes that populations adapt to social, economic, political, and biophysical environments through organizational innovations, and that systems grow ‘to the maximum size and complexity afforded by the technology for transportation and communication’ in reducing the time cost of maintaining the accessibility and exchange required by interdependent populations (Hawley 1986, p. 7). It is important to recognize that it is this theoretical framework, not the mere fact that aggregate data are used, that places research in the human ecological tradition.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

2. Contemporary Human Ecology

The intellectual lineage of human ecology traces from the emergence of plant and animal ecology in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and its application to human populations in the work of Park and Burgess (1921), McKenzie (1933), and other scholars at the University of Chicago. The approach of these scholars, while innovative, was ultimately limited in scope. Perhaps most limiting was the initial insistence that cultural variables be excluded from the purview of human ecology in favor of a focus on spatial patterns resulting from a process of unplanned competition. By contrast, the insights into demographic phenomena described herein depend almost entirely on contemporary human ecology (hereafter, human ecology) which denotes the body of theory and research that began with the publication in 1950 of Amos H. Hawley’s Human Ecology, a landmark volume which led to a major reorientation of the field. Hawley’s work dramatically shifted the focus from the description of physical features of the city and mapping of social phenomena to ‘the ways in which human populations organize in order to maintain themselves in given environments, thus relegating spatial analysis to a minor though still useful position in the discipline’ (Hawley 1986, p. 3). It is not spatial arrangements themselves, but rather the social relations often reflected in spatial patterns and processes, that are of interest to human ecologists (Frisbie and Kasarda 1988 for further discussion).

Albeit something of an oversimplification, the human ecological paradigm can be thought of as encompassing four broad categories of variables: population, organization, environment, and technology— codified by Duncan (1959, 1964) as the ecological complex bearing the acronym POET. It is crucial to recognize that, in human ecology, population is defined generically to mean ‘a number of units sharing one or more given characteristics … (which acquires) operational significance only when clothed with a set of institutions and located in a space-time context’ (Hawley 1998, pp. 11–12). At least since Hawley’s redirection of the field (1950), the primary unit of analysis for human ecology has been the organized population, not the individual units comprising populations. In addition, human ecology places a much heavier emphasis on analysis of the social and economic environment, as compared to the biophysical environment (Hawley 1998). This distinguishes (but does not isolate) human ecological concerns from those which characterize bioecology and the environmental movement.

The term ‘demographic behavior’ is used broadly here to refer, not only to the basic processes of fertility, mortality, and migration, but also to social demographic phenomena, with social demography defined as ‘the analysis of how general social and cultural factors are related to population structure and process’ (Ford and De Jong 1970, p. 4). In this context, an impressive range of human ecological insights into a large number of demographic issues might be identified. This research paper primarily emphasizes contributions to the study of the systemic attributes and processes involved in population growth and societal development, the distribution and redistribution of population, and intra-and interurban morphology. While this selectivity is logical in light of human ecology’s emphasis on systems, it warrants mention that the well-known contributions of human ecology to research on social networks and residential segregation are given little attention. Further, while much of the present discussion concentrates on research conducted in the US, human ecology has been drawn upon rather extensively in cross-national research (Frisbie and Al-Khalifah 1998).

3. Human Ecology’s General Theoretical Contribution To Macrolevel Demography

It is clear that human ecology has contributed substantially to the preservation and advance of macrolevel theory in the social and behavioral sciences, generally, and in demography, in particular (Poston and Frisbie 1998). However, in the mid-twentieth century, two events combined to diminish the interest of demographers and other social scientists in macrolevel analysis. The first was the publication of work dealing with what came to be known (erroneously) as the ‘ecological fallacy.’ Robinson (1950) argued that results of research in which aggregates are the units of analysis cannot be used to infer relationships among individuals and that a large proportion of research that employs aggregate data does so only because information on individuals is not available. The second was actually a sequence of events involving the emergence of modern techniques of sampling and survey analysis which greatly enhanced the opportunity for rigorous microlevel studies (Linz 1969). For a time, demography listed far toward reliance on individual-level research, even in the face of warnings by renowned scholars that the discipline was ill-served by a fixation at the microlevel (e.g., Ryder 1980).

A more balanced view prevails, partially due to the efforts of ‘ecological demographers’ both early on (Schnore 1961) and later (Namboodiri 1988). As it turned out, Robinson’s thesis was only partially correct. The problem identified by Robinson is not ‘ecological’ in nature, but rather an issue that arises whenever cross-level generalizations of any kind are contemplated. Moreover, many of the central tenets of human ecology are inherently macrolevel constructs devoid of any counterpart at the individual level. For example, the concept of the division of labor makes sense only when applied to groups. Analogous reasoning applies to many demographic variables. Individuals are born, they die, and in between they may migrate, but only groups, not individuals, have birth, mortality or migration rates.

A signal contribution of human ecology has thus been the development of a theoretical framework for a wide range of demographic studies of organized aggregates. Examples include investigations of the relationship between commodity exchange and position of cities in the US metropolitan hierarchy (Eberstein and Frisbie 1982), as well as in the worldwide system of cities (Meyer 1986), the effects on the volume and rate of migration, of functional niche and extent of the division of labor (Murdock et al. 1992, Poston and Mao 1996), changes in the social stratification of suburbs (Guest 1978, Krivo and Frisbie 1982), segregation of racial and ethnic populations (Massey and Denton 1989), and the ‘birth’ and ‘death’ rates of formal organizations (Carroll 1984, Hannan and Freeman 1977). Such work, in turn, offers a substantive grounding for mutlilevel analyses, in which, e.g., the behavior of individuals is partially explained in terms of the social or ecological context in which they exist.

4. Specific Insights On Demographic Phenomena

4.1 Population Growth

Perhaps no demographic issue has seized and held the attention of scholars, policy makers, the media, and the general public as that of rapid population growth. Interest in the ‘population explosion’ intensified circa 1970 in the wake of publications which predicted exhaustion of resources and irremediable environmental pollution if population and economic growth continued unchecked (Erlich 1968, Meadows et al. 1974). A wide range of less apocalyptic, but still highly disturbing, publications focused attention on less developed countries (LDCs) and the actual or anticipated deleterious consequences of rapid population growth for development and increases in the standard of living in these nations—effects epitomized by the piling up of excess rural populations in peripheral slums of huge cities (Davis 1975).

Early on, some scholars challenged the view that continued rapid population growth spelled worldwide collapse (see Davis 1990 for a summary of the position of ‘alarmists’ and ‘skeptics’). Regardless of whether one tends toward pessimism or optimism, it is evident that demography has to come to grips with the Malthusian contention that population growth will inevitably be limited by exhaustion of natural and/or nonrenewable resources. Before one can meaningfully discuss its utility for better understanding population growth, it is necessary to recognize that, in human ecological theory, population is regarded as a necessary, but not sufficient, condition. An important analytical implication is that population

cannot operate independent of organizational circumstances. In and of itself it cannot cause war, resource exhaustion, or environmental pollution, as Malthusians have argued. Such outcomes are explained as due to maladaptations or malfunctioning of organization (Hawley 1986, p. 26).

Human ecologists have also called attention to certain errant assumptions that are perhaps more apt to be found in popular or ‘vulgar’ interpretations than in Malthus’ work itself (Keyfitz 1982). Among the most troublesome of these is the naıve perspective that the concept of manageable population size can be operationalized as a ‘simple ratio of organisms to units of a resource or resources’—naıve because it fails to take into account ‘the manner in which the population is organized to use the resources’ (Hawley 1950, p. 151). This flaw apparently underlies the conclusion that concepts such as ‘carrying capacity’ and ‘limits to growth,’ have failed to provide either ‘analytic power, or foresight, instead of hindsight’ (Davis 1990, p. 13).

Constructive insights are found in the human ecological model of system change, growth, and equilibrium. In system terms, growth refers to ‘maturation… through the maximization of the potential for complexity and integration implicit in the technology for movement and communication possessed at a given point time’ (Hawley 1986, p. 52). This perspective has direct roots in Boulding’s (1953) theory of nonproportional change which suggests that a limit to growth occurs, not when some ratio of organisms to resources is reached, but when the communications and transportation costs involved in maintaining the coherence of a system become prohibitively high. Growth of systems can be expected to take the form of a logistic curve which describes a period of rapid growth which gives way to slow or no growth. Equilibrium is this view is a temporary state, and population increase will resume in combination with system expansion as additional organizational and technological inputs allow breaking through the upper asymptote imposed by the costs of movement and coordination of activities (Hawley 1986, 1998).

Applied specifically to demography, this insight might be translated as follows:

As to demographic growth, its initial acceleration is a natural byproduct of … economic transformation since, predictably, the fruits of economic improvement are in part used for obtaining better health and lowered mortality. Malthusian outcomes, however, need not be the inevitable result of rapid population growth. Such growth is transitory: given economic success, the spontaneous onset of ‘‘demographic transition’’ can be confidently expected. Pressure built into the reward mechanisms of modern industrial society induce behavioral changes that eventually lead to low fertility, hence to low or no population growth (Demeny 1990, p. 417).

Recent worldwide fertility declines are consistent with this perspective. A 1999 United Nations publication shows that the world total fertility rate (TFR= the number of children a female surviving to the end of her reproductive life would bear given prevailing age-specific fertility rates (Keyfitz and Flieger 1990, p. 16)), after hovering around 5.0 during the period 1950–70 had fallen precipitously to 2.93 in 1990–95, with an expected TFR =2.71 for 1995–2000 (UN 1999). By 1975–80, fertility in developed nations was already below replacement level (TFR =1.91; for replacement, TFR is approximately 2.1, allowing for mortality of children). In LDCs, the rate for 1990–95 was 3.27, but this represented a rather astonishing decline from TFR = 6.00 in 1965–70. Based on its medium variant, the UN (1999, pp. 520–1) projects that average fertility among today’s LDCs will fall to bare replacement level within the first four to five decades of the twenty-first century.

Of course, even with this major slowdown in population growth, 50 years into the twenty-first century, the world will still have a population much larger than today’s roughly six billion (UN 1999, US Agency for International Development 1999). Some scholars (e.g., Bongaarts and Feeney 1998) have argued that current low fertility rates are, at least in some contexts, temporarily, rather than permanently, depressed to below replacement, while others believe the contemporary trend is likely to be permanent or at least rather persistent (Lesthaeghe and Willens 1999).

5. Urbanization

The concentration, deconcentration, and organization of urban populations have been central to ecological theory and research. As noted, Hawley defined human ecology as the study of the form and development of the community, of which urban places are a prime example. Although neither the highly stylized spatial models of urban form and growth developed by Burgess and Park, nor those of other scholars, have remained central to urban studies, these heuristic representations had a basis in analytical constructs that are important building blocks for ecological theories of the distribution and interaction of populations in both intraurban and interurban systems.

5.1 Intraurban Systems: Land Use And Population Distribution

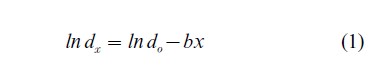

Among the most directly relevant of human ecological insights for understanding intrametropolitan systems are those having to do with land use and population concentration deconcentration. Of special interest is Burgess’ notion of geographical gradient as a basis for the hypothesis predicting an inverse relationship between intensity of land use by a population and distance from center to the periphery of cities (cf. Hawley 1971). This relationship, formalized by Colin Clark (1951), can be expressed in the form of natural logarithms as

where dx is the density of population at distance x from the center, do is the central density, and b is an empirically derived density gradient. Reflected in this equation is a theory of land use which begins with the premise that functional differentiation and interdependence of populations and organizations in a city require mutual accessibility. Since, ceteris paribus, the center of a city is the point most accessible to all other parts of the city, there will be competition for core location, thereby driving up the cost of land at or near the center which, in turn, requires that more intensive use must be made of space. As ease of access declines with distance from the core, so too does the cost of land and the intensity of its use (Berry and Kasarda 1977, Hawley 1971, Turner 1994). The magnitude of the insight afforded by the human ecological theory of urban land use for demographers and others interested in the distribution and redistribution of population is seen in the fact that the validity of this model has been demonstrated by research using data covering a period of over a century and a half and for more than 100 cities (Frisbie and Kasarda 1988, p. 634).

Ecological theory also predicts that reduction in the friction of movement of population, materials, and ideas over time and space will cause the slope of the gradient to become less and less steep. As modern means of transportation developed and dramatic advances were achieved in accumulating, processing, and disseminating information, simple models based on a core-to-periphery gradient in a monocentered city have become progressively less relevant as metropolitan areas have increasingly become multinodal. But, because it is the systemic relationships reflecting the need for mutual accessibility of functionally interdependent populations, not spatial patterns, per se, that are central to the theory, the relevance of the ecological perspective remains in the face of rapidly changing urban systems. To illustrate, in the 1970s, as documented by numerous scholars and summarized by Edmonston and Guterbock (1984), several factors seemed inimical to the continuation of the rapid pace of suburbanization. Transportation costs had risen dramatically due to the reduction of petroleum supplies by major producing nations, while income growth in constant dollars slowed notably and housing prices soared—all of which raised the cost of moving to, and commuting from, the urban periphery. In addition, demographic composition had shifted such that the types of families that had traditionally fueled movement to suburbs, i.e., larger households headed by couples of prime child-bearing age, became proportionately fewer. Taking the coefficients of Clark’s equation as dependent variables for more than 200 metropolitan areas, Edmonston and Guterbock demonstrated that mean central densities of cities continued to decline over a 25-year time span and that ‘the density gradient dropped consistently’ (1984, p. 918). That is, the initial concentration at the core of cities occurred due to the need for accessibility. The large negative sign of the density gradient reflected the less developed transportation and communications technology available during the early stage of city building, but the slope flattened as technological innovations emerged. When the cost of movement over time and space rose sharply in the 1970s, the deconcentration of population nevertheless continued because, by that time, jobs and market outlets (industrial parks and shopping malls), recreational facilities, and utilities had also expanded well into the urban periphery (Berry and Kasarda 1977, Edmonston and Guterbock 1984). Thus, in the face of altered social and economic conditions, the human ecological paradigm continues to be a reliable guide for research on population distribution and redistribution. The reason, in part, is due to the conceptualization of space as a time-cost variable. What organized populations seek to minimize is not distance between interdependent enitities, but the cost in time, effort, and other resources required for regular interaction (Stephan and McMullin 1981).

Another crucial aspect of intraurban population distribution in the US is residential segregation by race and ethnicity. However, a brief discussion is in order here because it is demographic analysis that has most fully documented segregation, and a substantial portion of the explanation for these findings has been provided by human ecological theory. A prime example is seen in the work of Massey and colleagues who, over many years, have traced the sharp separation of African Americans from whites (and the lower levels of separation of Latinos and Asians from whites), taking into account variation in socioeconomic status, nativity, and other factors (Massey 1979, Massey and Denton 1989, 1993, Farley and Frey 1994). Based on an examination of segregation in the US and five other nations, Massey concluded that ‘the operation of common processes of ethnic concentration and dispersal are well-summarized by the ecological model’ (Massey 1985, p. 315; emphasis added), especially as the model pertains to chain migration, invasion, and succession of populations, the urban economy, and the housing market. Although human ecological theory is much less helpful in accounting for black–white segregation, Massey and Eggers (1990) have usefully addressed this phenomenon in research on ‘the ecology of inequality.’

5.2 Interurban Systems: National And World Patterns

A useful point of departure for many demographers interested in intermetropolitan organization has been the classification of cities according to horizontal and vertical dimensions. The horizontal dimension refers to functional specialization of cities in various goods and services at various stages of production for the market, as operationalized in terms of types of industrial activities (Duncan et al. 1960, Frisbie and Kasarda 1988). The vertical dimension refers to the level of dominance exercised by cities in a metropolitan hierarchy as measured by performance of coordinative functions, including financial services and organization of the market (Duncan et al. 1960, Eberstein and Frisbie 1982, Wanner 1977) on a scale that may be regional, national, or international in scope (Frisbie and Kasarda 1988, Wilson 1984).

Moving down the ladder of abstraction leads to a crucial hypothesis, viz., that a positive association will exist between the performance of higher-order functions and extensiveness of involvement in the urban web of interdependence. An empirical test (Eberstein and Frisbie 1982), using data on 171 US urban centers, with metropolitan function defined as performance of financial, commercial, administrative, and distributive activities and extensiveness of interdependence measured in terms of volume and variety of trade flows and number of exchange linkages among urban centers, provided considerable support for this hypothesis. In a study of the world system of cities, Meyer concluded that ‘(t)he hypotheses of ecological dominance were confirmed’ (1986, p. 553). Specifically, Meyer found that, with a focus on the key functions of banking and finance, world core cities (e.g., New York, London, Tokyo) ‘dominate the peripheral metropolises of South America, and within the core the upper level metropolises exert even greater dominance than the lower level metropolises’ (1986, p. 553). In addition to the general support provided for ecological theory, such findings reinforce the social demographic point that ‘while all metropolises are large cities, not all large cities are metropolises. Population size is a concomitant; function is the keynote’ (Vance and Sutker 1954, p. 115).

6. Migration

‘Change without movement is impossible’ (Hawley 1950, p. 324). Based on this tenet, human ecology views migration (whether within or across national boundaries) as a means through which something approaching a balance between population size and life chances may be temporarily achieved. Many of the most fundamental concepts employed in migration research are rooted in human ecological theory, including the recognition that, because migration involves a destination as well as a place of origin, it is necessary to consider both ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors. Recently, human ecological models, which also include population size and distances between origin and destination as predictors, have been able to account for well over half the variation in migration streams of interstate migration in the US (Poston and Mao 1996) and interprovincial migration in China (Poston and Mao 1998). The ecological view of the push of ‘overpopulation’ as an impetus to migration refers not only to an excess of population to land, food, or some other natural resource, but more generally to availability of ecological niches in the form of job opportunities, especially as these are generated by the movement of capital (Hawley 1950).

Another contribution is seen in the notion of ‘chain migration,’ a phenomenon to which classical ecologists called attention. Chain migration means that ‘migrants do not select destinations randomly, but follow social networks … to specific jobs in particular neighborhoods of selected cities’ (Massey 1985, p. 318). The concept has enhanced our understanding of how residential segregation occurs and of how migrants adapt at destination through drawing on ‘social capital’ provided by co-ethnics (Massey 1985, 1991).

Clearly, the human ecological perspective must be supplemented by other theories of migration (Portes and Fernandez-Kelly 1989). One problem with the ‘push—pull’ model is that it cannot explain, ‘(g)iven the same set of expelling forces and factors of attraction, why is it that some individuals leave while others stay’ (Portes 1991, p. 76). This weakness is inherent in the macrolevel approach of human ecology. Microlevel studies essentially seek an answer to the question ‘Who moves and why?’ By contrast, for human ecological studies of migration, the central question is ‘Where do people go and why?’

While ecological theories of migration involve much more than a simple ‘push–pull’ hypothesis, there is, nevertheless, a certain tendency to neglect population movements that are forced or ‘impelled’ by political agents at origin (Petersen 1958). An analogous gap is evident at destination due to the lack of attention paid by ecologists to the impact of immigration policies instituted by receiving countries seeking to restrict, and/or influence the composition of, immigration flows (Freeman and Bean 1997). Further, despite the importance attributed by Hawley to capital flows as a determinant of immigration (1950, p. 330), research in human ecology seems to have failed to appreciate fully the importance of the penetration of capital for the creation of economic imbalances that stimulate immigration (Portes and Fernandez-Kelly 1989).

The theoretical contributions of human ecology to this line of research did not cease with the appearance of Human Ecology. Hawley has extended his own ideas concerning the spatial movement and redistribution of population, particularly with respect to urban-oriented migration (1971, 1986). More recently, as part of a comprehensive theory of ‘assembling of human populations’ that involves geopolitical as well as ecological processes, Turner has set forth a set of propositions that envisions the rate of net immigration as ‘a positive and additive function of: (a) the level of transportation and communication technologies, (b) the rate and extent of contact with external populations, (c) the differentiation as well as volume and velocity of markets, (d) the diversity of the population, and (e) the size of population settlements’ (Turner 1994, p. 88). Coupled with the notions of chain migration and population flows preceded by capital flows, Turner’s formulation seems highly pertinent to many of the international population flows that have characterized the twentieth century.

7. Summary

Contemporary human ecology has sustained and helped extend the theoretical foundation of macrolevel demography. It has also contributed in numerous ways to the understanding of specific demographic phenomena, as illustrated by reference to research on population growth, urban form and process, and migration, with brief attention given to residential segregation by race and ethnicity. While other examples could have been employed, it is palpable that human ecology provides a paradigm that, in spite of certain weaknesses and oversights, greatly facilitates comprehension of how populations grow and distribute themselves within, and adapt to, the natural and social environments.

Bibliography:

- Berry B J L, Kasarda J D 1977 Contemporary Urban Ecology. Macmillan, New York

- Bongaarts J, Feeney G 1998 On the quantum and tempo of fertility. Population and Development Review 24: 271–91

- Boulding K E 1953 Toward a general theory of growth. Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science 19: 326–40

- Carroll G R 1984 Organizational ecology. Annual Review of Sociology 10: 71–93

- Clark C 1951 Urban population densities. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A 114: 490–6

- Davis K 1975 Asia’s cities: problems and options. Population and Development Review 1: 71–86

- Davis K 1990 Population and resources: fact and interpretation. Population and Development Review 16(suppl.): 1–21

- Demeny P 1990 Tradeoffs between human numbers and material standards of living. Population and Development Review 16(suppl.): 408–21

- Duncan O D 1959 Human ecology and population studies. In: Hauser P M, Duncan O D (eds.) The Study of Population. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Duncan O D 1964 Social organization and the ecosystem. In: Faris R E L (ed.) Handbook of Modern Sociology. Rand-McNally, Chicago

- Duncan O D, Scott W R, Lieberson S, Duncan B 1960 Metropolis and Region. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD

- Eberstein I W, Frisbie W P 1982 Metropolitan function and interdependence in the US urban system. Social Forces 60: 676–700

- Edmonston B, Guterbock T M 1984 Is suburbanization slowing down?: Recent trends in population deconcentration in US metropolitan areas. Social Forces 62: 905–25

- Erlich P 1968 The Population Bomb. Ballentine, New York

- Farley R, Frey W H 1994 Changes in segregation of Whites from Blacks during the 1980s: Small steps towards a more integrated society. American Sociological Review 59: 23–45

- Ford T F, De Jong G F 1970 Social Demography. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

- Freeman G P, Bean F D 1997 Mexico and US worldwide immigration policy. In: Bean F D, de la Garza R O, Roberts B R, Weintraub S (eds.) At the Crossroads: Mexico and US Immigration Policy. Lanham, Boulder, CO

- Frisbie W P, Al-Khalifah H M 1998 Ecology’s contribution to cross-national theory and research. In: Micklin M, Poston Jr D L (eds.) Continuities in Sociological Human Ecology. Plenum, New York

- Frisbie W P, Kasarda J D 1988 Spatial processes. In: Smelser N J (ed.) Handbook of Sociology. Sage, Newbury Park, CA

- Guest A M 1978 Suburban social status: Persistence or evolution. American Sociological Review 43: 251–64

- Hannan M T, Freeman J 1977 The population ecology of organizations. American Journal of Sociology 82: 929–64

- Hawley A H 1950 Human Ecology: A Theory of Community Structure. Ronald, New York

- Hawley A H 1971 Urban Society: An Ecological Approach. Ronald, New York

- Hawley A H 1986 Human Ecology: A Theoretical Essay. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Hawley A H 1998 Human ecology, population and development. In: Micklin M, Poston Jr D L (eds.) Continuities in Sociological Human Ecology. Plenum, New York

- Keyfitz N 1982 The evolution of Malthus’s thought. In: Keyfitz N (ed.) Population Change and Social Policy. Abt Books, Cambridge, MA

- Keyfitz N, Flieger W 1990 World Population Growth and Aging. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Krivo L J, Frisbie W P 1982 Measuring change: the case of suburban status. Urban Affairs Quarterly 17: 419–44

- Lesthaeghe R, Willens P 1999 Is low fertility only a temporary phenomenon in the European Union. Population and Development Review 25: 211–28

- Linz J J 1969 Ecological analysis and survey research. In: Dogan M, Rokkan S (eds.) Quantitative Ecological Analysis in the Social Sciences. MIT Press, Cambridge MA

- Massey D S 1979 Residential segregation of Spanish Americans in United States urbanized areas. Demography 16: 553–63

- Massey D S 1985 Ethnic residential segregation: A theoretical synthesis and empirical review. Sociology and Social Research 69: 315–50

- Massey D S 1991 Economic development and international migration in comparative perspective. In: Diaz-Briquets S, Weintraub S (eds.) Determinants of Emigration From Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean. Westview Press, Boulder, CO

- Massey D S, Denton N A 1989 Hypersegregation in US metropolitan areas: Black and Hispanic segregation along five dimensions. Demography 26: 373–91

- Massey D S, Denton N A 1993 American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Massey D S, Eggers M L 1990 The ecology of inequality: Minorities and the concentration of poverty, 1970–1980. American Journal of Sociology 95: 1153–88

- McKenzie R D 1933 The Metropolitan Community. McGrawHill, New York

- Meadows D H, Meadows D L, Randers J, Behrens III W W 1974 Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome Project on the Predicament of Mankind, 2nd edn. Universe Books, New York

- Meyer D R 1986 The world system of cities: Relations between international financial metropolises and South American cities. Social Forces 64: 553–81

- Murdock S H, Backman K, Hwang S, Hamm R R 1992 Sustenance specialization and dominance in international and national ecosystems: Implications for post-1980 migration in counties in the United States. In: Jobes P C, Stinner W F, Wardwell J M (eds.) Community, Society and Migration: Noneconomic Migration in America. University Press of America, Lanham, MD

- Namboodiri K 1988 Ecological demography: Its place in sociology. American Sociological Review 53: 619–33

- Park R E, Burgess E W 1921 Introduction to the Science of Sociology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Petersen W 1958 A general typology of migration. American Sociological Review 23: 256–66

- Portes A 1991 Unauthorized immigration and immigration reform: Present trends and prospects. In: Diaz-Briquets S, Weintraub S (eds.) Determinants of Emigration from Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. Westview Press, Boulder, CO

- Portes A, Fernandez-Kelly M P 1989 Images of movement in a changing world: A review of current theories of international migration. International Review of Comparative Public Policy 1: 15–33

- Poston Jr D L, Frisbie W P 1998 Human ecology, sociology, and demography. In: Micklin M, Poston Jr D L (eds.) Continuities in Sociological Human Ecology. Plenum, New York

- Poston Jr D L, Mao M X 1996 An ecological investigation of interstate migration in the United States. Advances in Human Ecology 5: 303–42

- Poston Jr D L, Mao M X 1998 Interprovincial migration in China, 1985–1990. Research in Rural Sociology and Development 7: 227–50

- Robinson W S 1950 Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. American Sociological Review 15: 351–7

- Ryder N B 1980 Where do babies come from? In: Blalock Jr H M (ed.) Sociological Theory and Research: A Critical Appraisal. Free Press, New York

- Schnore L F 1961 The myth of human ecology. Sociological Inquiry 31: 128–39

- Stephan G E, McMullin D R 1981 The historical distribution of county seats in the United States: A review, critique, and test of time-minimization theory. American Sociological Review 46: 907–17

- Turner J H 1994 The assembling of human populations: Toward a synthesis of ecological and geopolitical theories. Advances in Human Ecology 3: 65–91

- United Nations 1999 World Population Prospects. United Nations, New York, Vol. 1

- United States Agency for International Development 1999 Popbriefs. USAID, Washington, DC

- Vance R B, Sutker S S 1954 Metropolitan dominance and integration in the urban South. In: Vance R B, Demerath N J (eds.) The Urban South. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC

- Wanner R A 1977 The dimensionality of the urban functional system. Demography 14: 519–37

- Wilson F D 1984 Urban ecology: Urbanization and systems of cities. Annual Review of Sociology 10: 283–307