View sample mental health research paper on women’s mental health. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Introduction

It is now widely understood that women’s well-being is multifactorial and is not only determined by biological factors and reproduction, but also by the effects of poverty, nutrition, stress, war, migration, and illness. Approaching mental health problems from a female perspective and mainstreaming it requires a broad framework of health for women that addresses mental health throughout the life cycle and in domains of both physical and mental health. First, we present evidence demonstrating that women disproportionately suffer from certain mental disorders and are more frequently subject to social issues that lead to mental illness and psychosocial distress. Subsequently, the article will deal with the nature and types of mental disorders in women; factors contributing to vulnerability; and specific issues such as poverty, migration, HIV, war, natural disasters, and pregnancy-related psychiatric problems. It will also describe landmark studies that have been conducted in the area and report interventions that have been attempted with a public health perspective.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Sex Differences And Mental Disorders

Which Mental Disorders Are More Common In Women?

Mental disorders affect women and men differently: some disorders are more common in women and some express themselves with different symptoms. Researchers are only now beginning to tease apart the contribution of various biological and psychosocial factors to mental health and mental disorders in both women and men.

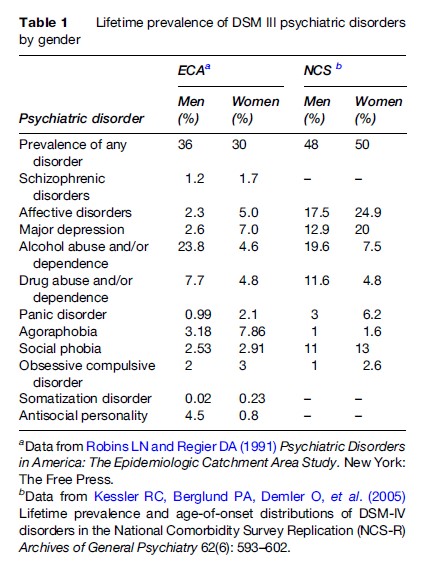

The disability-adjusted life year data recently tabulated by the World Bank reflect these differences. Depressive disorders account for close to 30% of the disability from neuropsychiatric disorders among women, but only 12.6% of that among men. Conversely, alcohol and drug dependence accounts for 31% of neuropsychiatric disability among men, but accounts for only 7% of the disability among women. These patterns for depression and general psychological distress and substance-abuse disorders are consistently documented in many quantitative studies carried out in societies throughout the world (Murray and Lopez, 1996). Table 1 describes the sex differences in prevalence of various psychiatric disorders.

Clinical Profile Of Various Mental Disorders In Women

Depression

Epidemiological and clinical studies have consistently documented that depression across different cultures is about twice as common in women as in men. Research shows that before adolescence and late in life, females and males experience depression at about the same frequency. Because the gender difference in depression is not seen until after puberty and decreases after menopause, scientists hypothesize that hormonal factors are involved in women’s greater vulnerability. In addition, the changing psychological status and role of women in society following puberty may place them in a vulnerable position in times of stress.

The manifestation of depression also tends to be different in women. They very often present with medically unexplained symptoms including vague aches and pains. Though severity has been reported to be similar in both genders, depression in women has been found to be associated with increased functional impairment and rates of suicide attempts are higher than in men. Women also tend to have onset of depression at an earlier age and often become symptomatic in mid-adolescence, while depression in men usually begins in their twenties. Longitudinal studies have shown that women develop more recurrent depression and the individual episodes last longer. Comorbid medical disorders such as thyroid problems, migraine, and rheumatologic disorders are particularly common. In addition, depression in women frequently coexists with other psychiatric disorders, particularly panic disorder and simple phobia. Other psychiatric conditions such as eating disorders and personality disorders are often associated with depression in women and add to functional impairment and diagnostic problems.

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, phobias, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with women outnumbering men for each of these illness categories. Women not only have a higher risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorders, but they are also more likely to develop long-term PTSD than males, with higher rates of co-occurring medical and psychiatric problems.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is the most chronic and disabling of the mental disorders, affecting about 1% of women and men worldwide. The illness typically appears earlier in men, usually in their late teens or early twenties, while women are generally affected in their twenties or early thirties. Thus, schizophrenia starts later in women compared to men, with a second peak in the menopausal period. The later age of onset confers some protection to women as they are usually better socialized and have a better clinical outcome.

Though the disease is reportedly less severe in women, they may have more depressive symptoms, paranoia, and auditory hallucinations than men and tend to respond better to typical antipsychotic medications. A significant proportion of women experience increased symptoms during the postpartum period and may also have significant problems in bonding with the child. Despite the better clinical outcome, women with schizophrenia often have to face higher stigma and face major problems in assimilating with the mainstream. In addition, they are prone to abuse – both physical and sexual – which puts them at further risk for physical and mental health problems. Additional problems that women with serious mental illness face include problems related to parenting, sexuality, and being more prone to drug side effects such as extrapyramidal symptoms, endocrine side effects, and osteoporosis.

Dementias: Alzheimer’s Disease

The main risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is increased age. Studies have shown that while the number of new cases of AD is similar in older adult women and men, the total number of existing cases is somewhat higher in women. Possible explanations include that AD may progress more slowly in women than in men, that women with AD may survive longer than men with AD, and that men, in general, do not live as long as women and die of other causes before AD has a chance to develop.

Caregivers of a person with AD are usually family members – often wives and daughters. The chronic stress often associated with the care-giving role can contribute to mental health problems; indeed, caregivers are much more likely to suffer from depression than the average person. Since women in general are at greater risk for depression than men, female caregivers of people with AD may be particularly vulnerable to depression.

Suicide

Although men are four times more likely than women to die by suicide, women report attempting suicide about two to three times as often as men. Self-inflicted injury, including suicide, ranks ninth out of the ten leading causes of disease burden for females worldwide. A recent study on causes of maternal mortality in the first year after childbirth in the UK reported suicide as being the most common reason for death among women within 1 year of childbirth.

Substance Use

Several studies have reported a marked difference in rates of all substance use, with men outnumbering women. However, complications related to substance use such as alcoholic liver disease, neurological problems including cognitive deficits, and sexual and reproductive consequences of substance use in women lead to substantial disability.

What Are The Factors That Contribute To Increased Vulnerability In Women To Mental Health Problems?

Life Stress And Mental Health Problems In Women

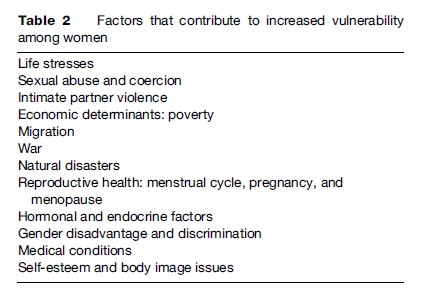

Serious adverse life events are clearly implicated in the onset of depression (Table 2). Most work investigating the relationship of stressful life events and major depression has largely or exclusively employed samples of women and few studies have examined sex differences with regard to stress and depression. However, initial research in this area has demonstrated that women are three times more likely than men to experience depression in response to stressful events. Brown and Harris were among the first to systematically describe the relationship of life stress to depression and subsequent research has confirmed the role of stress in women’s mental health.

One of the first research studies to look at the role of social factors in depression in women was published by George Brown and Tirril Harris in 1978 (Brown and Harris, 1978). This study, conducted in inner city London, delineated three important sets of factors in the causation and manifestation of depression among women. The factors included vulnerability factors (lack of a confiding and intimate relationship, three children under the age of 14 at home, and loss of the mother before the age of 11), provoking factors (stressful life events), and symptom formation factors (past history of depression, severe life event after the onset of depression, and any past loss). The study was among the first that described a conceptual and interactive model for the social and personal causes of depression in women.

Sexual Abuse And Sexual Coercion

Trauma experienced by women such as childhood sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, and intimate partner violence also have been consistently linked to higher rates of depression in women, as well as to other psychiatric conditions (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder, eating disorders) and physical illnesses. Features of abuse that determine the nature and severity of mental health problems include the duration of exposure to abuse, use of force, and relationship to the perpetrator. In addition, cognitive styles such as low self-esteem and even related appraisals also have an important impact on how women cope with abusive and traumatic life situations. In the context of sexual assault, characteristics such as degree and nature of physical force and perceived fear of death or injury significantly affect psychological outcome.

Intimate Partner Violence

Depression is also highly prevalent among women who experience male partner violence, which is often repetitive and concealed. Depression and posttraumatic stress disorder, which have substantial comorbidity, are the most prevalent mental health sequelae of intimate partner violence. Depression in women experiencing intimate partner violence has also been associated with other life stressors that often accompany domestic violence, such as younger age at marriage, childhood abuse, daily stressors, many children, coercive sex with an intimate partner, and negative life events. While some women might have chronic depression that is exacerbated by the stress of a violent relationship, there is also evidence that first episodes of depression can be triggered by such violence. Though most research focuses on physical and sexual abuse, the impact of psychological abuse on mental health is also evident. Most of the data point to the association of substance use (particularly alcohol use) in women experiencing intimate partner violence. Substance use has also been found to be a sequel to the experience of violence among women. A postulated explanation of substance use as an outcome of intimate partner violence is through posttraumatic stress disorder. Women with posttraumatic stress disorder might use drugs or alcohol to calm or cope with the specific groups of symptoms associated with posttraumatic stress disorder: Intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal. Women can also begin to abuse substances through their relationships with men or from wanting to escape the reality of intimate partner violence. It is important to address and understand these complex relations between intimate partner violence, mental health, and behavior to make an accurate diagnosis and intervene in substance abuse problems. In addition to mental health problems, women who experience violence use medical and emergency services more often and are known to present to primary care with unexplained somatic symptoms.

Poverty

Poverty among women has been steadily increasing and it has been linked to mental health problems among women. This association was observed more than two decades ago by Brown and Harris (1978), and this link has been established in recent studies. Affective disorders are common among both men and women living in poverty and it has been observed that more women live in poverty than men. Poverty among women increases their risk for exposure to traumatic life experiences such as physical and sexual victimization. These experiences at times serve as barriers to accessing mental health services. In addition, women in poverty find it difficult to access health care because of lack of insurance and transportation and inflexible jobs. Mental health problems, when untreated, can lead to severe disabilities for women in poverty. In addition, mental health problems, specifically depression, have been reported to contribute to significant economic burden in women living in poverty (Patel et al., 2007).

Migration

Migration involves uprooting oneself fully or partially from the familiar, traditional community and relocating in a foreign land. Immigration can be planned and voluntary for better prospects in life or it can be unplanned, unanticipated, and forced, as in the case of civic unrest, armed conflict, and violation of human rights. Migration always calls for making adaptations, as people traverse several interpersonal, cultural, language, ecological, and geographic boundaries. The sociocultural differences and scarcity of resources could lead to feelings of fear, isolation, alienation, and helplessness in migrants. Migration as such may not affect the mental health of the immigrants, but the process of migration and adaptation can cause increased stress and vulnerability to mental health problems. For instance, evidence from South Asian immigrant women in Canada suggests that these women are specifically at risk for mental health problems because of the rigid gender roles in the South Asian community that make smooth integration into the adopted country a challenge. Likewise, South Asian women residing in the UK were more likely to report anxiety and depressive symptoms compared to their male counterparts. Loss of social support, low social status, constraints in finances, and accessing health services were major stressors for immigrant women in Canada (Ahmad et al., 2004). Research studies conducted on divergent ethnic and racial immigrant groups residing in Europe found that complicated grief and posttraumatic stress disorder were noted to be common psychiatric problems among refugees and asylum seekers.

War

Wars are known to cause immense human suffering in several ways. War results in a shortage of food, water, fuel, and electricity that are basic requirements of every human being. During war, many civilians are exposed to traumatic experiences such as shooting and shelling and also seeing dead and wounded people, witnessing and experiencing violence, and injuries to self and others. Experiences of separation and displacement from relatives and forced migrations are very common. In addition to loss of valuable human resources, war results in damage of infrastructure and depletion of natural resources. There is substantial evidence on the mental health consequences of war for individuals. High rates of posttraumatic stress disorder as well as depressive and anxiety disorders were documented even among civilians. Studies documented inconsistent but high prevalence rates of PTSD among women affected by war. In addition, the aftermath or the postwar sociopolitical conditions are likely to contribute to mental health problems in women. For instance, life in Afghanistan has been disrupted for the past 20 years because of social and political disturbances. The war had extraordinary health outcomes for Afghan women, and women in Afghanistan have been found to have significantly poorer mental health compared to men (Cardozo, 2005).

Natural Disasters

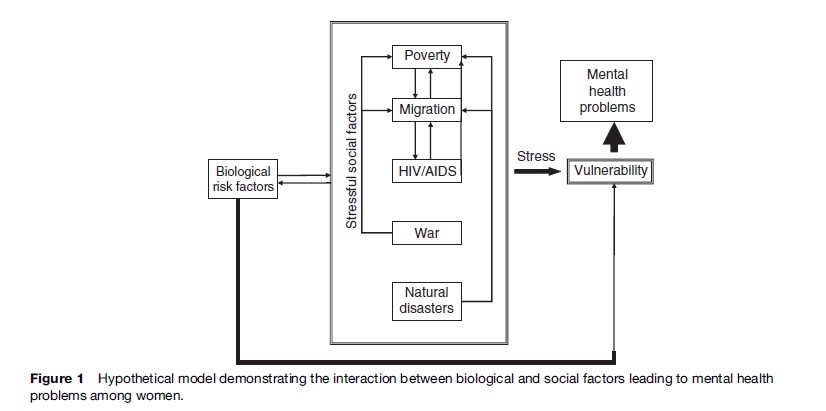

Natural disasters are out of human control but the consequences of natural disasters overlap with the consequences of war or combat. In both contexts, there is human suffering caused by damage to life, personal property, and infrastructure. Families are displaced and victims lose shelter. This is complicated further by immense shortages of food and drinking water. Several medical and psychological problems among the victims are major offshoots of natural disasters. A summary of research studies conducted between 1981 and 2004 in both developing and developed nations yielded consistent results with regard to the psychological consequences of disasters on women. PTSD and major depressive and anxiety disorders were the common mental health consequences. The gender of the victims predicted several post-disaster outcomes in many of these studies; consistently, women were more likely to be affected than men. For PTSD alone, the rates for women exceeded those for men by a ratio of 2:1. In a few studies, being married was found to be a risk factor because the severity of husbands’ symptoms predicted the severity of wives’ symptoms more than vice versa (Figure 1).

Clinical Interface Of Women’s Mental Health With Reproductive Health And Medical Disorders

Psychiatric Disorders In Relation To Pregnancy And The Postpartum Period

Studies on psychiatric disorders among pregnant women in community-derived samples have shown lifetime depression risk estimates between 10% and 25%, while studies that screened obstetric patients at random for depressive symptoms found that up to 20% of patients met criteria for a diagnosis of a depressive episode. Risk factors for depression during pregnancy include young age, low education, a large number of children, a history of child abuse, a personal or family history of mood disorder, and stressors such as marital dysfunction.

Marcus et al. (2003) found that one in five pregnant women experience depression, but few seek treatment. The stigma of having depression during pregnancy may prevent women from seeking active treatment because they may feel guilty for suffering during what is supposed to be a happy period. The impact of untreated depression during pregnancy is known to have negative effects on both mother and child.

Major Consequences Of Untreated Maternal Depression

In The Mother

Mothers with depression may suffer from impaired social function, emotional withdrawal, and excessive concern regarding their future ability to parent. They are less likely to regularly attend obstetrical visits or have regular ultrasounds and show lack of initiative and motivation to seek help, and experience a negative perception regarding any potential benefit of obstetric services. Mothers suffering from depression are also more likely to smoke or use alcohol and have lower-than-normal weight gain throughout pregnancy because of diminished appetite. Severe depression also carries the risk of self-injurious, psychotic, impulsive, and harmful behaviors. Untreated depression may have associated obstetric complications such as spontaneous abortion, bleeding during gestation, and spontaneous early labor.

In The Child

Untreated maternal depression has also been associated with low birth weight in babies, babies small for their gestational age, preterm deliveries, perinatal and birth complications, admission to a neonatal care unit, and neonatal growth retardation. Neurobehavioral effects include reduced attachment, reduced mother–child bonding, and delays in offspring’s’ cognitive and emotional development. Lower language achievements and long-term behavioral problems may also be seen in some children whose mothers suffered from depression.

Postpartum Psychiatric Disorders

Postpartum psychiatric disorders are unarguably one of the most complex groups of disorders that encompass human experience. The joy of having a baby coupled with distress caused by impaired mental health can render the experience particularly traumatic to the mother, infant, and family. History taking in overburdened emergency maternity wards usually does not allow for details about the mother’s psychiatric history, let alone her current emotional status. In addition, short hospital stays and lack of follow-up make early recognition of emotional disorders difficult. The consequences of undiagnosed and hence untreated puerperal disorders can have negative consequences both on the mother and the developing infant. Psychiatric disorders in the postpartum period include depression, anxiety-related disorders such as panic disorder and obsessive compulsive disorders, mother–infant bonding disorders and the relatively less common group of severe mental illness. In addition, women with preexisting psychiatric problems may also have worsening of symptoms in the postpartum period.

Epidemiology

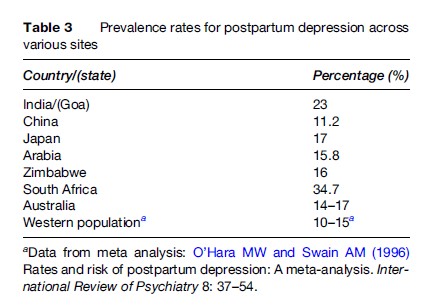

Epidemiological surveys by Kendell et al. (1987) and Terp et al. (1999) have established the incidence of postpartum psychosis as somewhat less than 1/1000 deliveries. Postpartum depression affects approximately 10–15% of all mothers in the developed world, while slightly higher rates have been reported from India (Patel, 2002) and South Africa. Table 3 gives the prevalence rates based on studies done in several countries around the world.

The presence of depression in the last trimester of pregnancy is a strong predictor of postpartum depression. The preference for male children, deeply rooted in some societies, coupled with the limited control a woman has over her reproductive health may make pregnancy a stressful experience for some women. Local cultural factors are also pertinent in shaping maternal socioaffective well-being. For example, in rural China, mother-in-law conflict was reported in nearly one-third of young women who attempted suicide, as reported by Pearson (2002). Similar data on the role of mothers-in-law in domestic violence in pregnancy are available from different cultures such as Hong Kong, India, Korea, and Japan.

Severe Mental Illness In The Postpartum Period

Psychoses in the postpartum period have been classified as organic psychosis, schizophrenia, mania, or acute psychosis. Several studies report a relationship between puerperal psychosis and bipolar disorders. Some of the common clinical features of psychosis in the postpartum include a polymorphic presentation, perplexity, confusion, emotional lability, and psychotic ideas related to the infant. In addition, preexisting severe mental illness can also worsen in the postpartum period. Severe mental illness after childbirth may raise several psychosocial issues, particularly related to safety of the mother and the infant. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths 1997–1999, carried out in the UK, reported that psychiatric disorder, and suicide in particular, was the leading cause of maternal death in the first year after childbirth. The study has highlighted the need for routine assessment of preexisting and recent-onset psychiatric disorder in obstetric settings. It also emphasized the need for specialized clinical services for mothers with severe mental illness.

Depression

The presentation of this group of disorders can be heterogeneous. Mothers with chronic dysthymia, prepartum depression continuing into the puerperium, depression associated with recent adversity, and bipolar depression all fall into this common heading. Postnatal depression can have untoward effects on infant development, and depression may lead to reduced interaction and irritability misdirected at the child.

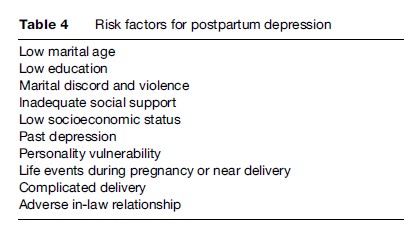

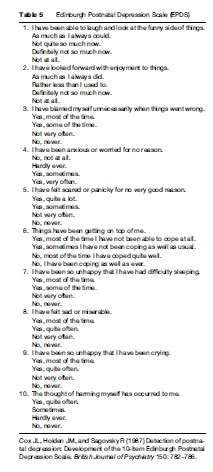

One of the most popular and widely used screening tools used for detection of postpartum depression is the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Table 5) originally designed by Cox et al. (1987). This scale is available in several languages around the world. A high score on this ten-item self-rating questionnaire needs to be followed by an interview clarifying the symptoms of depression and comorbid psychiatric disorders. In addition to detecting depression, it is also important to explore the wider context, including the mother’s life history, personality, and circumstances; the course of the pregnancy, including parturition and the puerperium; and relationships with the spouse, other children, family of origin and, especially, the infant. In addition to diagnosing depression and other disorders, one must identify vulnerability factors and the availability of support (Table 4).

Treatment And Prevention Of Maternal Mental Disorders

Several studies have assessed the efficacy of different forms of treatment and prevention of postpartum depression. These include interpersonal psychotherapy, home visits by nurses, prenatal and postnatal classes, debriefing visits, and continuity of care models. A recent metaanalysis on the efficacy of psychosocial interventions in preventing postpartum depression has reported that interventions that target at-risk women, are individually based, and are done in the postpartum period rather than during pregnancy appear to show more benefit. Interpersonal psychotherapy has also been used in the treatment of postpartum depression with some efficacy.

Acute treatment of bipolar illness and psychosis is usually with psychotropic drugs including mood stabilizers. However, knowledge regarding the safety of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers in pregnancy and lactation is needed and second-generation antipsychotics may be safer. Lithium and other mood stabilizers are useful in treatment of bipolar disorders provided they are used with monitoring and also following discussions with the mother and the family. Antidepressants are indicated for moderate to severe depression, especially when biological functions are impaired or there is prominent suicidal ideation. Inpatient care may be indicated in more severe cases and requires specialized nursing and psychiatric care.

Postpartum psychosis has a recurrence rate of at least one in five pregnancies and mothers with a past history of puerperal or nonpuerperal psychosis have an enhanced risk. There is some evidence that prophylaxis, given immediately after delivery, reduces this risk.

Mother–infant bonding disorders that can occur as a consequence of psychiatric problems or infant-related issues are treated depending on the cause. Play therapy and baby massage under supervision or done in a graduated manner are often quite effective.

Menstrual Cycle And Menopause

Mild mood changes in relation to the premenstrual phase have been reported commonly; however, significant mental health problems have been reported in 3–5% of women. This usually occurs in the form of late luteal phase dysphoric disorders, which are mainly characterized by mood changes that significantly impair social, personal, and occupational functioning.

Mental health problems in menopause may be attributable to a combination of factors including hormonal, cognitive, and life-stage-related causes. Psychosocial factors including exit events such as illness or death of spouse, retirement, and loneliness may contribute significantly to mental health in the postmenopausal stage.

While the emphasis of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) was more on the role of estrogen and progesterone on osteoporosis, breast cancer, and cardiovascular disease, the study also generated a large amount of data relevant to mental health. The WHIMS (Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study) found a lack of evidence for the role of hormone therapy (estrogen alone or estrogen and progesterone) in protection against dementia among older women. The study also has important findings in the area of quality of life and lifestyle issues related to physical health, alcohol use, trauma, and panic disorders in older women. The study included Caucasian, African-American, and Asian women, was conducted in the U.S., and has important implications in the care of women over 65 years of age.

Reproductive Health Problems And Women’s Mental Health

Infertility, female sterilization, and reproductive tract complaints have all been related to poor mental health in women. Infertility and the newer reproductive technologies are often fraught with uncertainties, leading to depression. Infertility in cultures where fertility and having children often determine the status of women has important implications for mental health. Vaginal discharge – both pathological (resulting from infections) and nonpathological – is often associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety. Women with somatic complaints and depression are known to present to clinics with a presenting complaint of vaginal discharge and need to be screened for mental health problems.

A recent study from West Africa (Coleman et al., 2006), explored associations between depression and reproductive health conditions in 565 rural African women of reproductive age. The weighted prevalence of depression in the community was 10%, but more importantly, being depressed was significantly associated with widowhood or divorce, infertility, and severe menstrual pain.

Malignancies And Impact On Mental Health

Cancer of the cervix and breast cancer are the commonest cancers among women (the former in the developing world) and have several mental health implications. Mental health influences help seeking, early detection, and participation in cancer screening programs. Subsequent to diagnosis, depressive disorders are common and may influence coping methods used in handling the illness. Studies done on women with breast cancer have emphasized the role of coping not only in the context of mental health but also in the progression of the disease.

HIV/AIDS

The efficacy of antiretroviral drugs has resulted in the decline in the incidence of AIDS cases in developed parts of the world but the proportion of women living with AIDS in resource-poor countries has been increasing steadily. Feelings of shame, guilt, fears related to stigma, death, and dying, concerns associated with childbearing and transmission of HIV to children are common sources of stress among women with HIV/AIDS. HIV-infected women face higher stigma and lesser social support than men. A high incidence of depressive symptoms and anxiety disorders among women with HIV has been found in recent studies. HIV-infected women were found to be four times more likely to report current major depressive disorder and report anxiety symptoms compared to HIV-seronegative women. In the current context of antiretroviral treatment being available to a growing number of HIV-infected women even in the developing world, the recent literature has reported that depressive symptoms among women with HIV could lead to poor antiretroviral treatment utilization and adherence (Cook et al., 2002). Early detection and treatment of mental health problems in HIV-infected women therefore may have an impact on help-seeking behaviors and medication compliance. In addition, psychosocial factors such as poor socioeconomic conditions, race, and ethnicity are also likely to be associated with mental health problems among women infected with HIV. For instance, HIV infected women in the United States are disproportionately African-American or Latina and often live in poverty, and are as a result vulnerable to several social disadvantages. Understanding the psychological response to AIDS among women and the psychosocial context in which AIDS occurs is vital to prevent mental health problems and improve adherence to treatment.

Medical Disorders And Impact On Mental Health

Several medical conditions, especially endocrinological diseases (such as thyroid and parathyroid disorders) and collagen vascular disorders occur more commonly in women. These can cause mental health problems in two ways, one resulting from direct neuropsychiatric effects and the other a consequence of the disability caused by these conditions. Pain and somatic symptoms in medical disorders can be worsened because of coexisting mood disorders, which are commoner among women.

Interventions

Primary Prevention

Health policies that incorporate mental health into public health and address women’s needs and concerns in different life stages can be developed in numerous ways. Health promotion through public health initiatives related to education, men’s attitudes toward women, gender discrimination, violence, safety, substance abuse, prenatal care, and regular health assessments of older women will help in preventing several mental health problems. Health policies must also face the challenge of formulating ethical but culturally sensitive responses to practices that are damaging to the emotional and physical health of women and girls (such as female circumcision, female infanticide, gender-specific abortion, and feeding practices that discriminate against girl children).

Secondary Prevention

Integrated health programs that address and handle the stigma of major mental illness, consequences of sexual or domestic violence, the consequences of gender discrimination, and the stress of poverty are an important part of public health. One of the more troubling mental health consequences of the general health status of communities is the effect on mothers of high infant and child mortality rates and high HIV infection rates affecting multiple family members across generations. Communication between health workers, physicians, and women patients (and often men as well) needs to be emphasized to facilitate disclosure of mental health issues by women to facilitate early detection. Training of nonmental health professionals in the use of simple screening tools to detect mental health problems such as the use of the General Health questionnaire or the EPDS (see the section titled ‘Depression’) will strengthen early detection efforts in primary care. Training and enhancing the competence of primary care physicians, mental health professionals, and health workers to detect and treat the consequences of domestic violence, sexual abuse, and psychological distress can also play an important role. Helplines for women in distress and suicide helplines have been shown to be effective for women in early and accessible help seeking in the community. Women in most communities will need services near their homes and without causing inconvenience to child care and family.

Tertiary Prevention

Skilled clinicians as well as broader multidisciplinary programs in the community with links to hospitals are necessary to address the more distressing and difficult needs of women with serious psychiatric problems. These services should also be available in other medical centers such as those dealing with oncology or HIV infection and in obstetric and gynecology clinics.

Although the social roots of many of these problems mean that they cannot be managed only with medical interventions, there is a need to strengthen the potential role of the health-care system. In addition, there should be increased consumer participation by women in formulating health-care policies and programs.

Conclusion

Women’s mental health needs to be considered in the context of the interaction of physical, reproductive, and biological factors with social, political, and economic issues at stake. The multiple roles played by women such as childbearing and child rearing, running the family, caring for sick relatives, and, in an increasing proportion of families, earning income are likely to lead to considerable stress. The reproductive roles of women, such as their expected role of bearing children, the consequences of infertility, and the failure to produce a male child in some cultures are examples of mechanisms that make women vulnerable to suffering from mental disorders. In addition, biological factors may play a major role, particularly in reproductive life events such as pregnancy, the postpartum period, and menopause as well as in the clinical manifestations of various mental health problems.

Public health and social policies aimed at improving the social status of women are needed along with those targeting the entire spectrum of women’s health needs. Efforts to improve and enhance social and mental health services and programs aimed at increasing the competence of professionals are also required.

Bibliography:

- Ahmad F, Shik A, Vanza R, et al. (2004) Voices of South Asian women. Immigration and Mental Health 40: 113–129.

- Brown GW and Harris T (1978) Social Origins of Depression. A Study of Psychiatric Disorder in Women. London: Tavistock.

- Cardozo BL (2005) Mental health of women in postwar Afghanistan. Journal of Women’s Health 14: 285–293.

- Coleman R, Morison L, Paine K, Powell RA, and Walraven G (2006) Women’s reproductive health and depression: A community survey in the Gambia West Africa. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41(9): 720–727.

- Cook JA, Cohen MH, Burke J, et al. (2002) Effects of depressive symptoms and mental health quality of life on use of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-seropositive women. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 30: 401–409.

- Cox JL, Holden JM, and Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry 150: 782–786.

- Kendell RE, Chalmers JC, and Platz C (1987) Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. British Journal of Psychiatry 150: 662–673.

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Demler O, et al. (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Archives of General Psychiatry 62(6): 593–602.

- Marcus SM, Flynn HA, Blow FC, et al. (2003) Depressive symptoms among pregnant women screened in obstetrics settings. Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmont) 12: 373–380.

- Murray CJL and Lopez AD (eds.) (1996) The Global Burden of Disease and Injury Series, vol. 1: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Cambridge MA: Harvard School of Public Health.

- O’Hara MW and Swain AM (1996) Rates and risk of postpartum depression: A meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry 8: 37–54.

- Patel V, Rodrigues M, and DeSouza N (2002) Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: A study of mothers in Goa India. American Journal of Psychiatry 159: 43–47.

- Patel V, Chisholm D, Kirkwood BR, and Mabey D (2007) Prioritizing health problems in women in developing countries: Comparing the financial burden of reproductive tract infections, anaemia and depressive disorders in a community survey in India. Tropical Medicine and International Health 12(1): 130–139.

- Pearson V (2002) Attempted suicide among young rural women in the People’s Republic of China: Possibilities for prevention. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 32: 359–369.

- Robins LN and Regier DA (1991) Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. New York: The Free Press.

- Terp IM and Mortensen PB (1999) Post-partum psychoses: Clinical diagnoses and relative risk of admission after parturition. British Journal of Psychiatry 172: 521–526.

- Benjamin L, Hankin L, and Abramson Y (2001) Development of gender differences in depression: an elaborated cognitive vulnerabilitytransactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin 127: 773–796.

- Carta MG, Bernal M, Hardoy MC, et al. (2005) Migration and mental health in Europe (The State of the Mental Health in Europe Working Group: Appendix I): Review. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health 1: 13.

- Fischback RL and Herbert B (1997) Domestic violence and mental health: Correlates and conundrums within and across cultures. Social Science and Medicine 45: 1161–1170.

- Judith L, Lindsey W, Rhonda S, et al. (2006) PRISM (Program of Resources Information and Support for Mothers): A community-randomized trial to reduce depression and improve women’s physical health six months after birth. BioMed Central Public Health 6: 37.

- Kornstein SG and Clayton AH (eds.) (2003) Women’s Mental Health: A Comprehensive Textbook. New York: Guilford Press.

- Mazure CM, Keita GP, and Blehar MG (2002) Summit on Women and Depression: Proceedings and Recommendations. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Miranda J and Green B (1999) The need for mental health services research focusing on poor young women. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 2: 73–80.

- Oates M (2003) Perinatal psychiatric disorders – A leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. British Medical Bulletin 67: 219–229.

- Patel V, Araya R, de Lima A, et al. (1999) Women, poverty and common mental disorders in four restructuring societies. Social Science and Medicine 49: 1461–1471.

- Rehaman A, Iqbal Z, Bum J, et al. (2004) Impact of maternal depression on infant nutritional status and illness: A cohort study. Archives of General Psychiatry 61(9): 946.

- Watson M, Homewood J, Havilland J, et al. (2005) Influence of psychological response on breast cancer survival: 10-year follow-up of a population-based cohort. European Journal of Cancer 41(12): 1710–1714.

- http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/ – Center for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV/AIDS.

- http://www.who.int/mental_health/resources/gender/en/ – Gender and Women’s Mental Health, World Health Organization.

- http://www.womensmentalhealth.org/ – Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health.

- http://www.ncptsd.va.gov/ncmain/index.jsp – National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, United States Department of Veterans Affairs.

- http://www.whi.org/ – Women’s Health Initiative.

- http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/67.pdf – Women’s Mental Health: An evidence-based review, World Health Organization.