View sample mental health research paper on mental health resources and services. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Introduction

Although substantial information is available on the burden that mental and behavioral disorders place on society, until recently, very little was known about the resources available in different countries to alleviate these problems. Most of the available information on mental health resources was related to a few high-income countries. Furthermore, because available studies had used different units of measurement, the information that was accessible was not comparable across different countries or over time. In 2000, the World Health Organization launched Project Atlas to address this gap. The objectives of this project include the collection, compilation, and dissemination of relevant information about mental health resources in different countries.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Burden Of Mental Disorders

According to World Health Report for 2001, approximately 450 million people alive today have mental or neurological disorders or suffer from psychosocial problems, such as those related to alcohol and drug abuse. It is estimated that neuropsychiatric disorders account for 14% of the global burden of disease (WHO, 2004a; Prince et al., 2007). Currently, major depression ranks fourth in the ten leading causes of the global burden of diseases. If projections are correct, within the next 20 years, it will become the second leading cause of global disease burden. While neuropsychiatric disorders account for 27.2% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost in high-income countries (World Bank, 2004) in comparison to 8.6% in low-income countries (WHO, 2004b), in terms of actual caseload, three-fourths of those affected by neuropsychiatric disorders live in developing countries.

It is now obvious that the social and economic burden of mental illness is enormous. In addition, mental illnesses impose the burden of human suffering and stigma, discrimination and humiliation on the affected people and their families.

Public Health Approach To Mental Health

The importance of mental health has been recognized by WHO since its origin and is reflected by the definition of health in the WHO Constitution as ‘‘not merely the absence of disease or infirmity,’’ but rather ‘‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being’’ (United Nations, 2006: 186). Mental health is as important as physical health to the overall well-being of individuals, societies, and countries. Yet only a small minority of people suffering from a mental or behavioral disorder are receiving treatment. The World Mental Health Surveys (Demyttenaere et al., 2004) in 14 countries in the Americas, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia that covered six less developed and eight developed countries showed that even for serious disorders that were associated with substantial role disability, almost two-fifths of cases in developed countries and four-fifths in less developed countries received no treatment in the 12 months before the interview.

Advances in neuroscience and behavioral medicine have shown that, like many physical illnesses, mental and behavioral disorders are the result of a complex interaction between biological, psychological, and social factors. While there is still much to be learned, we already have the knowledge and power to reduce the burden of mental and behavioral disorders worldwide. Effective psychiatric care provision, indeed, is not a matter of sophisticated technologies, but rather a matter of equitable and rational organization of human resources. The World Mental Health Survey (Demyttenaere et al., 2004) showed that due to the high prevalence of mild and subthreshold cases, the number of those who received treatment for mild disorders far exceeded the number of untreated serious cases in every country. It suggested that reallocation of treatment resources could substantially decrease the problem of unmet need for treatment. As the ultimate stewards of any health system, governments must take the responsibility for ensuring that appropriate mental health policies are developed and implemented.

Mental Health At The International Level

Some of the important statements of international bodies like the United Nations including its specialized agency – the World Health Organization, the World Psychiatric Association, and the World Federation for Mental Health are detailed in the following paragraphs.

The United Nations resolution on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health adopted in 2003 states that the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health is a human right, and that such right derives from the inherent dignity of the human person.

The United Nations mental health principles for protection of persons with mental illness and the improvement of mental health care addresses issues such as the right to consent to treatment, protection of minors, standards of care, resources for mental health facilities, etc.

The United Nations standard rules on equalization of opportunities for persons with disability is an ambitious set of practical principles aimed at the equal exercise of rights by individuals with disabilities, of which a portion of individuals with mental disorders constitute a subgroup. It covers preconditions for equal participation (awareness raising, medical care, rehabilitation, and support services), target areas (e.g., accessibility, employment, family life and personal integrity, culture, religion, etc.), and guidelines on how the standard rules can be implemented and monitored. The rules have been strengthened by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN, 2006). The convention does not establish any new rights but rather emphasizes and consolidates the existing rights and freedoms of persons with disabilities and the international commitments of States. It defines disability as an element of human diversity and praises the contributions of persons with disabilities to society. It prohibits obstacles to the participation and promotes the active inclusion of persons with disabilities in society. The long-term goal of this Convention is to change the way the public perceives persons with disabilities, thus ultimately changing society as a whole.

The World Health Organization recognizes that mental health problems are of major importance to all societies and to all age groups and are significant contributors to the burden of disease and loss of quality of life. It is working toward a greater understanding of the mental health issues among policy makers and other partners to facilitate effective development of policies and programs to strengthen and protect mental health (WHO, 2002).

The World Psychiatric Association’s ethical guidelines on psychiatric practice (Hawaii Declaration in 1977, its amendment in Vienna in 1983, and the Madrid Declaration of 1996) prohibit abuse and treatment against a patient’s will unless such treatment is necessary for the welfare and safety of the patient and others. It emphasizes information and advice to the patient or caregiver on details of management, confidentiality, and the ethics of research.

The World Federation for Mental Health Declaration of Human Rights and Mental Health, first adopted in 1989, mentions that the diagnosis of mental illness by a mental health practitioner should be in accordance with accepted medical, psychological, scientific, and ethical standards. It states that the fundamental rights of mentally or emotionally ill or distressed persons shall be the same as those of all other citizens (e.g., right to coercion-free, dignified, humane, and qualified treatment; right to privacy and confidentiality; right to protection from physical or psychological abuse; right to adequate information about clinical status, etc.). The Declaration also mentions that all mentally ill persons have the right to be treated under the same professional and ethical standards as other ill persons.

Current State Of Mental Health Resources In The World

Project Atlas was launched by WHO in 2000 in an attempt to map mental health resources in the world (Saxena et al., 2002). The analyses of the global and regional data collected in 2001 were compiled and presented in the publication Atlas: Mental Health Resources in the World (WHO, 2001b), and individual country profiles and some further analyses were presented in Atlas: Country Profiles of Mental Health Resources in the World, 2001 (WHO, 2001a). Atlas 2005 was a part of the second set of publications from the project and it presented country profiles and detailed analyses of global and regional data (WHO, 2005; Saxena et al., 2006).

Information for this project was obtained from the focal points for mental health in the Ministries of Health in each WHO Member State, Associate Member, and Area through WHO Regional Offices (Saraceno and Saxena, 2002). Also, for Atlas 2005, comprehensive literature searches on epidemiological data pertaining to mental health and mental health services and resources (focusing on low and middle-income countries) were conducted. Information was also obtained from documents received from countries, travel reports submitted by WHO staff, feedback from experts and member associations of the World Psychiatric Association, and data available with WHO regional offices (WHO, 2005; Saxena et al., 2006).

Any comparison of data collected in the years 2001 (Atlas 2001) and 2004 (Atlas 2005) would benefit from the understanding that some of the changes involve relatively few countries reporting changes in status, and that this may reflect reporting error or unreliability rather than genuine trends. It should also be remembered that the denominator for the two data sets (years 2001 and 2004) is often different because many countries responded to questions in 2004 that they had been unable to answer previously.

National Policies And Legislation On Mental Health

Governments, as the ultimate stewards of mental health, have to assume the responsibility for the complex activities required to improve mental health services and care. Mental health policy, programs, and legislation are necessary steps for significant and sustained action.

Mental Health Policy

Mental health policy is a specifically written document of the government or Ministry of Health containing the goals for improving the mental health situation of the country, the priorities among those goals, and the main directions for attaining them. It may include the following components: Advocacy for mental health goals, promotion of mental well-being, prevention of mental disorders, treatment of mental disorders, and rehabilitation to help mentally ill individuals achieve optimum social and psychological functioning.

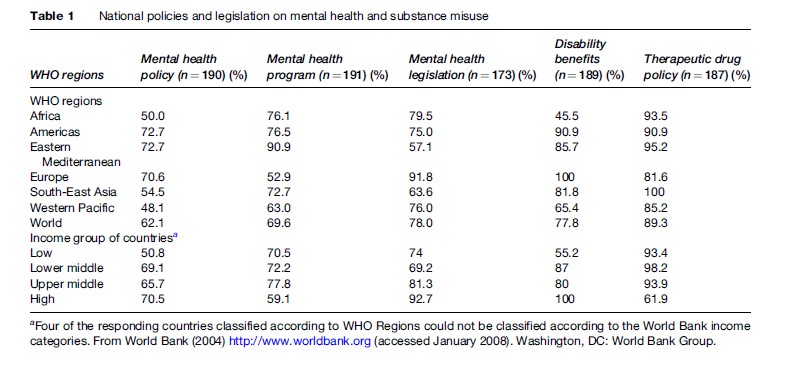

Only 62.1% of countries, accounting for 68.3% of the world population, have a mental health policy. In the African Region, approximately half of the countries do not have a mental health policy. A mental health policy is present in 51%, 70%, 68%, and 70% of countries of the low-income, lower-middle-income, upper-middle-income, and high-income countries, respectively. Mental health policies of most countries that have them cover most of the broad domains such as treatment (98.1%), prevention (95.3%), rehabilitation (93.4%), promotion (91.4%), and advocacy (80.4%). Policies in some countries also addressed other components such as intersect oral collaboration, social assistance, human resource development, and improvement of facilities for the underserved (e.g., Maoris in New Zealand).

Many developed countries such as the Scandinavian countries, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand have comprehensive national mental health policies. Some countries without a national mental health policy may still have good mental health services, e.g., some European countries do not have a stated policy but have well-developed action plans, and others such as the United States have a policy at the state or provincial level rather than the national level. On the other hand, it is possible that a country with a mental health policy may not have implemented its policy completely (Table 1).

National Mental Health Program

A national mental health program is a national plan of action that includes the broad and specific lines of action required to give effect to the policy. It helps to prioritize mental health issues in a country, sets time frames, and provides for budgetary support. Most countries with national mental health programs have emphasized deinstitutionalization, community-based care, and intersectoral collaboration. At times these programs also lend support to other specific populations (e.g., children and adolescents, the elderly, refugees, indigenous people); specific conditions (e.g., depression, suicide, HIV-related mental disorders) or specific issues such as domestic violence.

Seventy percent of countries, accounting for 91% of the world population, have a national mental health program. In the European Region, only 52.9% of countries have a program. In keeping with this, only 59.1% of high-income countries have specified their national mental health programs. On one hand, the low figures can be explained by the fact that many of these countries have laid down plans in various sectors of mental health (rather than a unified plan) or have plans at the state or provincial level (rather than at a national level); on the other hand, they point to the relative neglect of mental health in otherwise well-resourced countries. It is essential to revise programs as needs and management issues change over time. Nearly 11% of the programs date from before 1980 and it is unlikely therefore that deinstitutionalization and use of the newer psychotropic drugs would figure prominently in them.

Countries such as Norway and the Netherlands have well-defined programs. Importantly, some countries with limited resources such as Chile, Egypt, Jordan, India, Mexico, and the Philippines also have established programs. In the African Region, Niger has recently developed a program, Ghana updated its program in 2000, and Zambia is in the process of developing one.

Mental Health Legislation

Mental health legislation provides for the protection of the basic human and civil rights of people with mental disorders and deals with treatment facilities, personnel, professional training, and service structure. Some countries such as Cuba, Hungary, Iceland, and Spain include mental health legislation within their laws on general health.

Seventy-eight percent of countries, accounting for 69.1% of the world population, have specific mental health legislation. In the Eastern Mediterranean Region, only 57.1% of countries have laws in the field of mental health, compared with 97.8% of countries in the European Region. There is a large disparity between countries in different income groups, with 93% of high-income countries having specific mental health legislation, and 69% and 74% of lower-middle-income and low-income countries having such legislation.

Earlier legislation tried to isolate dangerous mentally disordered patients from the community, but more recently the focus has shifted toward ensuring consistency with international human rights obligations. This suggests that legislation needs to be updated and revised on a regular basis to make it comprehensive and in line with international norms. Scotland provides an example of a process where consumers, service providers, and policy makers were actively involved in revising legislation. Many other countries such as Jordan, Niger, Uganda, the UK, Zambia, etc., are also in the process of revising existing legislation. On the other hand, almost one-sixth of countries have mental health legislation that dates from before 1960, when the majority of the current effective methods for treating mental disorders were not available and focus on human rights was deficient.

Policy On Disability Benefits

Disability benefits are benefits that accrue to persons with illnesses that reduce their capacity to function as a legal right (from public funds). While disability benefits for physical illnesses exist in most countries, disability benefits for mental illnesses do not. Even when they do, they are often inadequate, difficult to obtain, and those affected are often unaware that they exist.

Some disability benefit is provided in 77.8% of countries that account for 93% of the world’s population. While provisions for disability benefits exist in only 45.5% and 65.4% of countries in the African and South-East Asian Regions, respectively, such provisions have been made in all countries in the European Region. Categorization of countries by World Bank (2004) income groups revealed that only 55.2% of countries in the low-income group provide disability benefits for mental illness, compared with nearly five-sixths of countries in middle-income groups and all countries in the high-income group.

Countries such as Austria, France, Germany, Spain, the UK, the United States, have well-developed (and rigorously implemented) legislation on disability benefits. In many countries, provision of disability benefit is limited to small one-time monetary help, paid leave for a specified duration, or early retirement with a pension. Also, the disbursement of disability benefits is often restricted to specific groups (e.g., those with severe chronic mental disorders, employed personnel) or by procedural difficulties (lack of uniform assessment procedures).

Policy On Therapeutic Drugs

A therapeutic drug policy is a document endorsed by the Ministry of Health or the government to ensure accessibility and availability of essential therapeutic drugs. The essential list of drugs is usually adapted from the WHO Model List of Essential Drugs. The therapeutic drug policy often specifies the number and types of drugs to be made available to health workers at each level of the health service according to the functions of the workers and the conditions they are required to treat. A country may specify an essential list of drugs even in the absence of a therapeutic drug policy.

Almost 90% of countries report the existence of a therapeutic drug policy or essential list of drugs. More than four-fifths of countries in all WHO regions, including all countries in the South-East Asia Region, have a therapeutic drug policy/essential list of drugs. While, more than 90% of low and middle-income countries have a therapeutic drug policy/essential list of drugs, only 61% of high-income countries have them. This is probably related to the fact that therapeutic medications are governed by independent/other (nonfederal) agencies in these countries; nonetheless, it could lead to inequities in the provision of therapeutic medication to their populations. Two-thirds of the policies or essential lists of drugs were formulated after 1990. Antidepressants such as serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and atypical antipsychotics are also included in the list of essential drugs in some countries.

Overall, there was a slight increase in number of countries with mental health policy, mental health legislation, and therapeutic drug policy/essential drug list between the two rounds of data collection (2001 and 2004). The trend for legislation was more pronounced in the African (8.4%) and American (7.1%) regions. More countries were providing disability benefits; the change in this regard was most marked in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (10.7%) and the lower middle-income (9.5%) countries.

Budgetary Issues

A specified budget for mental health denotes the regular allocation within a country’s budget for actions directed at achievement of mental health objectives, e.g., implementation of mental health policies or programs or the establishment of psychiatric care facilities. Many countries do not make a specific allocation for mental health in their national budgets, but make such allocations at the provincial or state level. In other countries, where mental health is a part of the primary health-care system, it is difficult to ascertain the specific budget for mental health care.

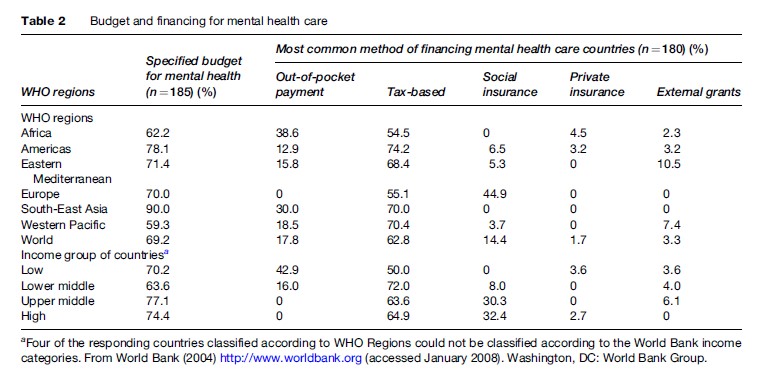

In spite of the importance of a separate mental health budget within the total health budget, 30.8% of countries reported not having a specified budget for mental health care. In the Regions of Africa and the Western Pacific, such a budget is present in 62.2% and 59.3% of countries, respectively. On the other hand, 78.1% of countries in the American Region have a specified budget for mental health care.

One hundred and one countries provided information on the actual budget for mental health. One-fifth of these countries, covering a population of more than 1 billion, spend less than 1% of the total health budget on mental health. In the Regions of Africa and South-East Asia, 70.0% and 50.0% of countries, respectively, spend less than 1% of their health budget on mental health care. In contrast, more than 61.5% of countries in the European Region spend more than 5% of their health budget on mental health care. Categorization of countries according to World Bank (2004) income groups showed that 29.2% of low-income countries versus 0.7% of high-income countries spend less than 1% of their budget on mental health care.

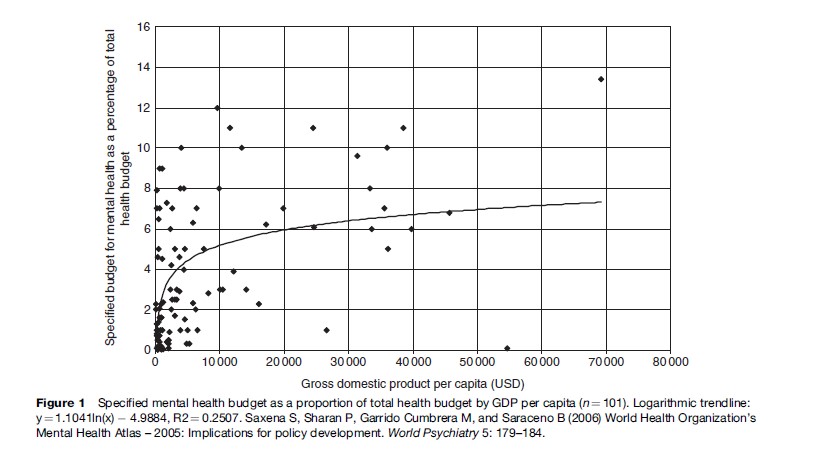

Examination of the percentage of the mental health budget out of the total health budget versus the gross domestic product (GDP) for countries shows that countries that have higher GDP tend to earmark higher percentages of their total health budget for mental health. A logarithmic trend line (Figure 1) confirms this relationship. This illustrates the double disadvantage suffered by mental health in low-income countries; they have, even proportionally, a lower mental health budget. It is obvious that mental health is one of the most neglected areas of health in poor countries. Even considering the limitations of the current data, it is obvious that countries spending less than 1% of their total health budget on mental health care need to substantially increase it (Table 2).

Methods Of Financing

Since mental health financing is a relatively new area of investigation, most countries do not have the information required to provide accurate data on this index. The ratings provided are at best approximations, because this project only sought information ranked by order of importance of each source of financing.

The dominant methods of financing mental health in countries are out-of-pocket payment (17.8%), tax-based funding (62.8%), social insurance (everyone above a certain income level is required to contribute a fixed percentage of their income to a government-administered health insurance fund, which pays for part or all of the consumer’s mental health services; 14.4%), private insurance (1.7%), and external grants to countries by other countries or international organizations (3.3%). Across all WHO Regions, tax-based financing is the dominant method of financing mental health care in one-half to three-quarters of countries. Out-of-pocket payment is the dominant method of financing in 38.6% and 30% of countries in the African and South-East Asia Regions, respectively. In the European Region, social insurance is the primary method of financing in 44.9% of countries.

Figure 1 Specified mental health budget as a proportion of total health budget by GDP per capita (n = 101). Logarithmic trendline: y = 1.1041ln(x) -4.9884, R2 = 0.2507. Saxena S, Sharan P, Garrido Cumbrera M, and Saraceno B (2006) World Health Organization’s Mental Health Atlas – 2005: Implications for policy development. World Psychiatry 5: 179–184.

Categorization of countries according to World Bank (2004) income groups showed that tax-based care is the primary method of financing mental health in countries of all income groups. Out-of-pocket payment is the primary method of financing in 42.9% of low-income countries, while social insurance is the primary method of financing in 32.4% and 30.3% of high-income and upper-middle-income countries, respectively.

Out-of-pocket payment is unsatisfactory because severe mental disorders can lead to heavy financial expenditure. Mental health care should preferably be financed through taxes or social insurance, as private health insurance is also inequitable because it favors the more affluent sections of society and is often more restrictive in the coverage of mental illness than in the coverage of somatic illness.

A comparison of data between 2001 and 2004 showed that 23.3% more countries in South-East Asia Region reported that they had a specific budget for mental health. There was a decrease in emphasis on out-of-pocket payment (5.4% and 10.8%, respectively) and an increase in emphasis on tax-based systems (7.5% and 7.8%, respectively) in the American and Eastern Mediterranean Regions, while in the Western Pacific Region there was an increase in emphasis on out-of-pocket payment (11.2%) and social insurance (5.7%). In terms of income groups of countries, a decrease in emphasis on social insurance (8.9%) and an increase in emphasis on private insurance (8.0%) were observed in lower-middle-income countries; and a decrease in emphasis on social insurance (8.3%) occurred in high-income countries.

Resources For Mental Health Services

Mental Health Beds

The term psychiatric bed denotes a bed maintained for continuous use by patients with mental disorders. These beds are located in public and private psychiatric hospitals, general hospitals, hospitals for special groups of the population such as the elderly and children, military hospitals, long-term rehabilitation centers, etc. Though inpatient facilities are essential for managing patients with acute mental disorders, efforts should be made to reduce beds in stand-alone psychiatric hospitals and increase beds in general hospitals and long-term community rehabilitation centers. Some regions within countries such as Italy have completely eliminated asylum-like psychiatric hospitals.

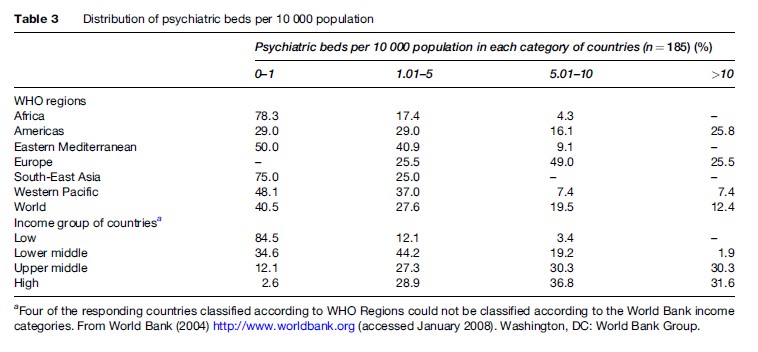

The median number of psychiatric beds in the world per 10 000 population is 1.69 (mean, 4.36; standard deviation, 5.47). The median figure per 10 000 population varies from 0.33 in the South-East Asia Region and 0.34 in African Region to 8.00 in the European Region. The median figure per 10 000 population in low-income countries is 0.68 in comparison to 8.94 in high-income countries.

More than two-thirds of psychiatric beds in the world are located in mental hospitals, while only about one-fifth are found in general hospitals. More than four-fifths of beds in the Eastern Mediterranean, South-East Asia, and American Regions are in mental hospitals. The Western Pacific Region has the highest proportion of psychiatric beds in general hospitals (34.5%). On the other hand, only about 10% of beds in South-East Asia, American, and Eastern Mediterranean regions are in the general hospital setting. More than three-fourths of beds in low and middle-income countries and approximately 55% of beds in high-income countries are located in mental hospitals.

In 40.5% of countries, covering 44.7% of the population, there is less than one psychiatric bed per 10 000 population. In the South-East Asia and African Regions, 94.9% and 82.9% of the population, respectively, has access to less than one bed per 10 000 population. On the other hand, in the European Region only 25.7% of the population has access to less than five psychiatric beds per 10 000 population. Nearly five-sixths of low-income countries, covering 96% of the world population, have less than one psychiatric bed per 10 000 population. In high-income countries, only roughly 10% of the population has access to fewer than five psychiatric beds per 10 000 population.

A comparison of data between 2001 and 2004 showed that there was a decrease in the median number of beds in regions that had high bed-to-population ratios, i.e., American (a decrease of 0.9 per 10 000 population) and European (a decrease of 0.7 per 10 000 population) Regions, and an increase in regions with intermediate bed-to-population ratio, i.e., in the Eastern Mediterranean (an increase of 0.24 per 10 000 population) and Western Pacific (an increase of 0.08 per 10 000 population) Regions. No change was observed in regions with low bed-to-population ratio, i.e., in the African and South-East Asian Regions. A decrease in number of beds was noted in high-income countries (a decrease of 1.20 per 10 000 population), an increase in middle-income countries, particularly upper-middle-income countries (an increase of 2.30 per 10 000 population), and no change was observed for low-income countries. There was a decrease in proportion of mental hospital beds (denominator: all psychiatric beds) in the African (5%), European (7%), and Western Pacific (9.2%) Regions and low-income countries (11.7%). A general trend toward an increase (3.9%) in the proportion of general hospital beds to total beds was observed; this was relatively marked for the African (8.6%), European (11.7%), and Western Pacific (11.8%) Regions (Table 3).

Human Resources

Inputs from mental health professionals are required in patient care, policy advice, administration, and for training other personnel.

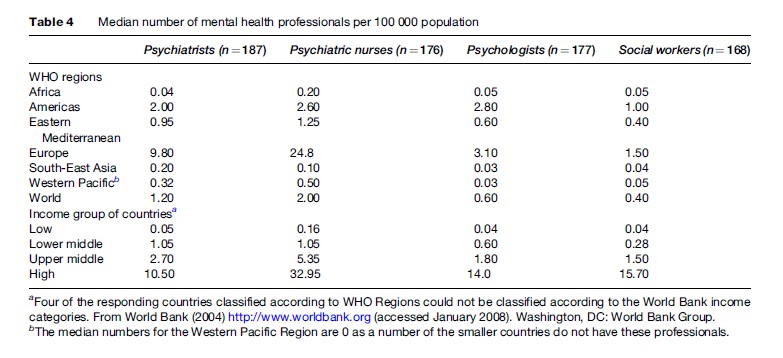

The median number of mental health professionals per 100 000 population in the world is quite low (psychiatrists, 1.2; psychiatric nurses, 2; psychologists working in mental health, 0.6; social workers in mental health, 0.4), even though some countries may have over reported the number of psychiatric nurses, psychologists, and social workers in mental health fields (by mistakenly including general nurses working in the mental health field, and psychologists and social workers employed in general health and related sectors such as education).

Psychiatrists

The term psychiatrist denotes a medical doctor who has had at least 2 years of postgraduate training in psychiatry at a recognized teaching institution. The median number of psychiatrists per 100 000 population varies from 0.04 in the African Region to 9.80 in the European Region. In actual numbers, this amounts to approximately 1800 psychiatrists for 702 million people in the African Region compared to more than 89 000 psychiatrists for 879 million people in the European Region. The median figure for low-income countries is 0.05 per 100 000 population and that for high-income countries is 10.5 per 100 000 population.

In 47.6% of countries, covering 46.5% of the world’s population, there is less than one psychiatrist per 100 000 population. All countries in the South-East Asia Region and 89.1% of countries in the African Region have fewer than one psychiatrist per 100 000 population. Fivesixths (87.9%) of low-income countries have fewer than one psychiatrist per 100 000 population. Even when available, most psychiatrists are based in large cities and large populations living in rural areas have no access to them (Table 4).

Psychiatric Nurses

The term psychiatric nurse denotes a graduate of a recognized, university-level nursing school with a specialization in mental health. Psychiatric nurses are registered with the local nursing board (or equivalent) and work in a mental health-care setting. The median number of psychiatric nurses per 100 000 population varies from 0.1 in the South-East Asia Region to 24.8 in the European Region; and 0.16 in low-income countries to 32.95 in high-income countries. More than three-fourths of countries in the South-East Asia Region and in low-income countries have access to fewer than one psychiatric nurse per 100 000 population. In many developed and in some developing countries such as Botswana, Fiji, Ghana, Jamaica, and Tanzania, community psychiatric nurses contribute significantly to mental health care.

Psychologists Working In Mental Health

The term psychologist working in mental health denotes a graduate from a recognized, university-level school of psychology with a specialization in clinical psychology. These psychologists are registered with the local board of psychologists (or equivalent) and work in a mental health setting.

The median number of psychologists per 100 000 population varies from 0.03 in the South-East Asia and Western Pacific Region to 3.10 in the European Region, and from 0.04 in low-income countries to 14.0 in high-income countries. There is fewer than one psychologist per 100 000 population in 61.6% of countries, accounting for 66.0% of the world’s population. Ninety percent or more of the population in South-East Asian and African Regions and of low-income countries have access to fewer than one psychologist per 100 000 population.

Social Workers Working In Mental Health

The term social worker working in mental health denotes a graduate from a recognized, university-level school of social work, registered with the local board of social workers (or equivalent) and working in a mental health setting.

The median number of social workers working in mental health per 100 000 population varies from 0.04 in the South-East Asian Region to 1.5 in the European Region, and from 0.04 in low-income countries to 15.7 in high-income countries. In 64% of countries, accounting for three-fourths of the world’s population, there is fewer than one social worker per 100 000 population. In the African and Eastern Mediterranean Regions, more than 85% of the countries have access to fewer than one social worker per 100 000 population. Nearly 92.7% of low-income countries are served by fewer than one social worker per 100 000 population, while 38.7% of high-income countries are served by approximately ten social workers per 100 000 population.

A comparison of data between 2001 and 2004 showed that there was an increase in the number of mental health professionals in the world. The greatest increase was noted for psychologists engaged in mental health care (increase in median: 0.2 per 100 000 population, greater improvement occured in American and European Regions and upper middle-income group countries), and social workers engaged in mental health care (increase in median: 0.1 per 100 000 population, greater improvement occured in the European Region). When the median number of psychiatrists per 100 000 population was compared, it was seen that an increase had occurred in the European Regions (0.8) and in high-income countries (1.5). The South-East Asia Region showed a decrease in the number of psychiatrists (by approximately 40%) and psychiatric nurses (by roughly 60%). A decrease (roughly 20%) in the number of psychiatric nurses was reported in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Availability of more accurate figures as well as the flight of professionals to more affluent countries could be reasons for this trend.

There was a decrease (5.1%) in the number of countries with fewer than one psychiatrist per 100 000 population. This trend was more pronounced in the African and American Regions and in middle-income countries. Also, there was a decrease (6.7%) in the number of countries with fewer than one psychologist per 100 000 population. This trend was supported by figures for the American, European, and Eastern Mediterranean Regions and in low-income and upper-middle-income countries. Similarly, fewer (9.7%) countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region reported having fewer than one social worker per 100 000 population.

Primary And Community Care

Primary Care

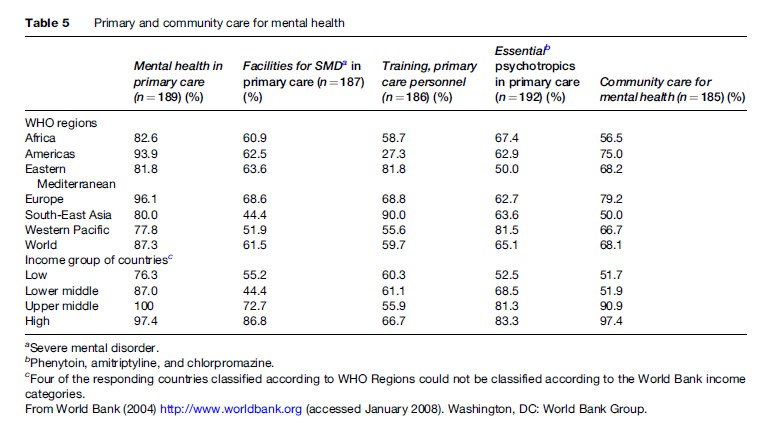

Mental health in primary care can be defined as the provision of basic preventive and curative mental health at the first level of the health-care system. In many countries, a nonspecialist who can refer complex cases to a more specialized mental health professional provides such care. Most mental disorders can be managed effectively at the primary care level if adequate resources are made available. Shifting mental health care to primary level also helps to reduce stigma, improves early detection and treatment, leads to cost efficiency and savings, and partly offsets limitations of mental health resources through the use of community resources (WHO, 2001a).

Mental health facilities at the primary level are reported to be present in 87.3% of countries that cover 96.5% of the world’s population. They are available in more than 77% of countries in the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific Regions and in approximately 95% of countries in the Americas and European Region. Across income groups, they are present in 76.3% of low-income countries and 97.4% of high-income countries. However, in reality, the population coverage is lower, as primary care services are not evenly distributed.

Treatment facilities for severe mental disorders in primary care settings were reported to be available in only 61.5% of countries in the world, covering 52.8% of the population. Such facilities are available in only 44.4% of countries in the South-East Asia Region. Across countries of different income groups, such facilities are available in 55.2% of low-income countries, 44.4% of lower-middle-income countries, and 86.8% of high-income countries. Treatment facilities for severe mental disorders in primary care settings across different countries also vary greatly. Most countries provide only follow-up care to the severely mentally ill in primary health-care facilities.

Mental health-care facilities in primary care are an integral part of the system in countries such as Australia, Austria, Italy, the Netherlands, the UK, and the United States. Integration of mental health into primary care has been found to be useful in countries such as Barbados, Cambodia, China, India, Iran, Jamaica, Nepal, and Zimbabwe (Table 5).

Training Of Primary Care Personnel

Training of primary care personnel involves the provision of essential knowledge and skills in identification, prevention, and care of mental disorders. Approximately 59% of countries have some training facilities for primary care personnel in the field of mental health. Whereas 90% of countries of the South-East Asia Region have such facilities, the same are available in only 41.9% of countries in the American Region. Many high-income countries of the European and American Regions provide regular training programs for doctors, nurses, and social workers working at primary care level. Some other countries such as Cambodia, Pakistan, Botswana, and Lesotho have also developed training facilities for primary care professionals.

Therapeutic Psychotropic Medication

Project Atlas sought information on the availability in primary care, the most common basic strength, and the cost of a specific list of drugs. Among antiepileptics, phenobarbital is available in 93% and phenytoin in 77% of countries. Amitriptyline, an antidepressant, is available in 86.4% of countries. Among antipsychotics, chlorpromazine is available in 91.4% and haloperidol in 91.8% of countries. Lithium, a mood stabilizer, is available in 65.4% of countries. Carbamazepine and sodium valproate, which are antiepileptics with mood-stabilizing properties are available in 91.4% and 67.4% of countries, respectively. Anti-Parkinson drugs are available in fewer countries, with levodopa, carbidopa, and biperiden being available in only 61.9%, 51.1%, and 43.5% of countries, respectively. Almost two-thirds of countries report that they make the three essential drugs: Amitriptyline (an antidepressant), chlorpromazine (an antipsychotic), and phenytoin (an antiepileptic) available in primary care. However, in many countries these drugs are either not available at all primary care centers or are not available at all times.

Community Care

Community mental health care includes provision of crisis support, protected housing, and sheltered employment in addition to management of disorders to address the multiple needs of individuals. Community-based services can lead to early intervention and limit the stigma of treatment. They can improve functional outcomes and quality of life of individuals with chronic mental disorders, and are cost-effective and respectful of human rights.

Community care facilities exist in only 68.1% of countries, covering 83.3% of the world population. In the African, Eastern Mediterranean, and South-East Asian Regions, such facilities are present in roughly half the countries. Across different income groups, community mental health facilities are present in 51.7% of the low-income and in 97.4% of the high-income countries. Countries such as Australia, Canada, Finland, Norway, the UK, and the United States, among others, have well-established community care facilities. Some Latin American countries have undertaken innovative services that provide useful demonstration experiences, for example in Argentina, Brazil, and Nicaragua. Other countries such as Barbados, Ghana, and Qatar have also developed some community care facilities. Services of traditional healers are being used as part of community care in many countries such as Cambodia, Guinea, Niger, Nigeria, and Senegal.

A comparison of 2001 and 2004 data showed that more countries (13.6%) in the Eastern Mediterranean Region had made treatment for severe mental disorders available in primary care. However, a 15.5% reduction was noted in the number of countries that made the three essential psychotropic drugs (amitriptyline, chlorpromazine, and phenytoin) available in primary care. This is mainly reflective of the fact that some countries, particularly in the European Region, added newer psychotropics to their essential list of drugs.

Monitoring Mental Health Systems

Monitoring is necessary to assess the effectiveness of mental health prevention and treatment programs and to identify its deficits. Indicators for monitoring should include data on clients of mental health services, quality of the services rendered, and general measures of the mental health of communities.

Mental Health Reporting Systems

Annual reporting systems cover health and health services functions and utilization of allocated funds. Annual mental health reporting systems exist in 75.7% of countries. They are reported to be present in 100% and 87.5% of countries, respectively, of South-East Asian and European Regions versus only 57.8% of countries in the African Region. Only 62.1% of low-income countries have an annual mental health reporting system compared with 86.1% of high-income countries. A comparison of data between 2001 and 2004 showed that a greater number of countries in the African (5.5%), American (8.1%), and South-East Asian (10%) Regions and the lower-middle-income group (9.3%) reported the presence of mental health reporting systems.

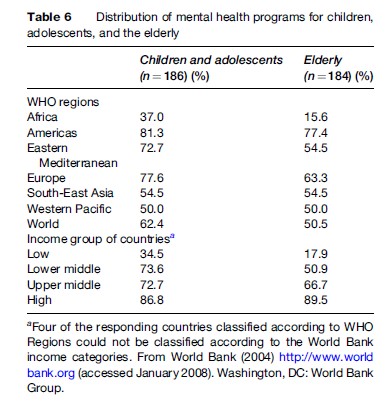

Programs For Special Populations

Programs for special populations are programs that address the mental health concerns (including social integration) of the most vulnerable and disorder-prone groups of the population. Programs for indigenous people are present in 14.8%, for minority groups in 16.5%, for refugees in 26.2%, for disaster-affected populations in 37.7%, for elderly persons in 50.5%, and for children in 62.4% of countries.

With 42.6% of its population made up of children (below 14 years), the African Region has programs for children in only 37% of countries, compared to 77.6% of countries in the European Region, where children account for 19.1% of the total population. Whereas 86.8% of high-income countries have a program for children, only 34.5% of low-income countries have one.

Programs for the elderly exist in 15.6% of countries in the African Region, in comparison to 77.4% of countries in the Region of the Americas. Such programs are present in 89.5% of high-income countries but in only 17.9% of low-income countries.

A comparison of data between 2001 and 2004 showed that there was an increase in services for children and the elderly in countries of the American (9.9% and 9.7%, respectively) and Western Pacific (7.7% and 11.5%, respectively) Regions. Similarly, services for children and the elderly increased in the lower-middle-income (13.3% and 5.6%, respectively) and upper-middle-income (7% and 9.6%, respectively) countries (Table 6).

Current Emphases In Psychiatric Care

Human Rights

The persisting question is how to balance the civil rights of mentally ill individuals against the limitations on their freedom required by society and contemporary healing techniques. Violation of human rights can be perpetrated both by neglecting patients through carelessness and by forcing them into restraining or even violent care systems. To prevent abuses, there is an urgent need to improve the quality of mental health care, to strengthen the management of institutions, and to closely monitor the rights of the mentally ill.

People with mental disorders are entitled to the enjoyment and protection of their fundamental human rights. The fundamental human rights obligations covered in the three instruments that make up what is known as the International Bill of Rights (the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights) include the protection against discrimination; the right to health including the right to access rehabilitation services; the right to dignity; the right to community integration; the right to reasonable accommodation; the right to liberty and security of person; and the need for affirmative action to protect the rights of persons with disabilities, which includes persons with mental disorders; and protection against torture, cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

Deinstitutionalization And Care In The Community

Deinstitutionalization is a complex process in which reduction of beds in stand-alone mental hospitals is associated with implementation of a network of community alternatives that can avoid the institutionalization of individuals with mental illness. Neither closure of mental hospitals without provision of extramural alternatives (which can lead to homelessness and trans institutionalization in prisons, nursing homes, etc.), nor creation of extramural alternatives without restriction on admission to mental hospitals (adding new services eventually recruits new patients but leaves the mental hospital unaffected) is optimal. In many European countries (e.g., Italy, Denmark, Finland, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom) and the United States, a substantial shift from a hospital-based to a community-based system has already taken place.

The deinstitutionalization process has also begun in some Latin American countries, for example Brazil, based on the policy guidelines of the Caracas Declaration. The principles set forth in this declaration refer to the need to develop psychiatric care that is closely linked to primary care and within the framework of the local health system. Deinstitutionalization has also been started in countries such as Burkina Faso, Croatia, Czech Republic, Jamaica, Iran, and Lithuania.

Integration With General And Primary Health Care

Many patients with psychological problems seek treatment from general health services. Studies conducted by WHO in many countries have shown that between 10% and 20% of primary care patients meet diagnostic criteria for psychiatric conditions (Harding et al., 1980). The WHO advocates that mental health care should be decentralized and integrated into primary health care, with the necessary tasks carried out as far as possible by general health workers rather than specialists in mental health. Equipping primary health-care workers to deal with mental health problems avoids wasted effort and cost. Importantly, the responsibility for mental health is not an extra burden for primary health-care services; on the contrary, it increases their effectiveness. Experiences in China, India, and African countries show that adequate training of primary health-care workers to early recognition and management of psychological disorders can reduce institutionalization and improve clients’ mental health.

Consumer And Family Involvement

The involvement of consumers and family is closely related to community-based management. Communities, families, and consumers can be included in the development and decision making of policies, programs, and services. This should lead to services becoming better tailored to people’s needs. Consumer and family associations have emerged as a major force in creating reciprocal social networks between mentally ill persons. Consumer and family movements have a long and important tradition in the United States and Europe, and recently similar movements have emerged in Latin America, Asia, and Western Pacific Regions. As a positive and promising example, in recent years, the Brazilian Ministry of Health gave impressive support to consumers and family organizations, which are now actively influencing the mental health policy, advocating for their rights and taking part in decision making in service organizations.

Conclusions And Future Directions

It is clear that mental disorders cause considerable burden on individuals, families, and societies and are of immense public health importance. Yet, they are underrecognized, undertreated, and underprioritized the world over, even though effective management options are available and psychiatric care provision does not require sophisticated technologies. In addition, the rights of mentally ill people (which includes the right to access to care) are often trampled upon.

Project Atlas, launched by WHO in 2000 in an attempt to map mental health resources in the world, has presented a worrisome picture. Global mental health resources continue to remain low and are grossly inadequate to respond to the high level of need. Regional imbalances and differences across income groups of countries persist. These data emphasize the urgent need to enhance resources devoted to mental health, especially in low and middle-income countries. WHO has argued for a substantial enhancement in resources invested in mental health (WHO, 2003).

The ten recommendations of the World Health Report 2001 (WHO, 2001c) remain as valid today as when they were made:

- Provide treatment in primary care.

- Make psychotropic drugs available.

- Give care in the community.

- Educate the public.

- Involve communities, families, and consumers.

- Establish national policies, programs, and legislation.

- Develop human resources.

- Link with other sectors.

- Monitor community mental health.

- Support more research.

These recommendations can be adapted by every country according to its needs and its resources.

Fortunately, the importance of mental health and rights issues is beginning to be recognized and international and national bodies have started advocating for effective, equitable, and rights-based mental health services. The world is also witnessing a welcome trend toward integration of mental health into primary health care, deinstitutionalization, community care, and involvement of communities, families, and consumers in the development of policies, programs, and services.

Bibliography:

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al. (2004) Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Journal of American Medical Association 291: 2581–2590.

- Harding TW, Arango MV, Baltzar J, et al. (1980) Mental disorders in primary health care: A study of their frequency and diagnosis in four developing countries. Psychological Medicine 10: 231–241.

- Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, et al. (2007) No health without mental health. Lancet 370: 859–877.

- Saraceno B and Saxena S (2002) Mental health resources in the world: Results from Project Atlas of the WHO. World Psychiatry 1: 40–44.

- Saxena S, Maulik PK, O’Connell K, and Saraceno B (2002) Mental health care in primary community settings: Result from WHO’s Project Atlas. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 48: 83–85.

- Saxena S, Sharan P, Garrido Cumbrera M, and Saraceno B (2006) World Health Organization’s Mental Health Atlas – 2005: Implications for policy development. World Psychiatry 5: 179–184.

- United Nations (2006) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/documents/ tccconve.pdf . New York: United Nations.

- World Bank (2004) The World Bank. http://www.worldbank.org. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- World Health Organization (2001a) Atlas: Country Profiles on Mental Health Resources. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2001b) Atlas: Mental Health Resources in the World 2001. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2001c) The World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2002) Strengthening Mental Health, EB109. R8. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2003) Investing in Mental Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2004a) The World Health Report 2004: Changing History. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2004b) Revised Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2002 Estimates. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_regional_2002_revised/en/.

- World Health Organization (2005) Mental Health Atlas 2005. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Department of Health Human Services (1999) Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Pittsburgh, PA: Department of Health and Human Services, United States Public Health Service.

- Ustun TB and Sartorius N (eds.) (1995) Mental Illness in General Health Care. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons.

- World Health Organization (2005) WHO Resource Book on Mental Health, Human Rights and Legislation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlasmnh/en/ – Mental Health Atlas.