Sample Dialectical Behavior Therapy Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is a comprehensive cognitive-behavioral treatment program designed for complex difficult-to-treat mental disorders. Originally developed to treat chronically suicidal patients, the treatment evolved into a treatment for suicidal patients who also meet criteria for borderline personality disorder (BPD), and has since been adapted for BPD patients with presenting problems other than suicidal behaviors and for other disorders of emotion regulation. DBT combines the basic strategies of behavior therapy with Eastern mindfulness and teaching practices, residing within an overall frame of a dialectical worldview that emphasizes the synthesis of opposites. The fundamental dialectical tension in DBT is between an overarching emphasis on validation and acceptance of the patient on the one hand, with persistent attention to behavioral change on the other. Change strategies in DBT include analysis of maladaptive behavior chains, problem solving techniques, behavioral skills training, management of contingencies (i.e., reinforcers, punishment), cognitive modification, and exposure-based strategies. DBT acceptance procedures consist of mindfulness (e.g., attention to the present moment, assuming a nonjudgmental stance, and focusing on effectiveness) and a variety of validation and stylistic strategies.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Development Of DBT

DBT, developed by Linehan in the early 1980s, grew out of a series of failed attempts to apply the standard cognitive and behavior therapy protocols of the early 1980s to chronically suicidal patients. Difficulties that emerged included the following. (a) Focusing on client change, either by improving motivation or by enhancing skills, was often experienced as invalidating by individuals meeting criteria for BPD and often precipitated withdrawal from therapy, attacks on the therapist, or vacillation between these behaviors. (b) Teaching and strengthening new skills was extraordinarily difficult, if not impossible, within the context of a therapy oriented to reducing the motivation to die. (c) The rigorous control of the therapy agenda needed for skills training did not allow for sufficient attention to be given to motivational issues. (d) New behavioral coping skills were extraordinarily difficult to remember and apply when the patient was in a state of crisis. (e) Borderline individuals often unwittingly reinforced therapists for iatrogenic treatment (e.g., a client might stop attacking the therapist if the therapist changed the subject away from topics the client was afraid to discuss) and punished them for effective treatment strategies (e.g., a client may respond with a drug overdose when the therapist refuses to recommend hospitalization stays that reinforce suicide threats).

Three modifications to standard behavior therapy were made to take these factors into account. First, strategies that more clearly reflected radical acceptance and validation of clients’ current capacities and behavioral functioning were added to the treatment. The synthesis of acceptance and change within the treatment as a whole and within each treatment interaction led to adding the term ‘dialectical’ to the name of the treatment. This dialectical emphasis brings together in DBT the ‘technologies of change’ based both on principles of learning and crises theory and the ‘technologies of acceptance’ (so to speak) drawn from principles of Eastern Zen and Western contemplative practices. Second, the therapy as a whole was split into several different components, each focusing on a specific aspect of treatment. The components in standard outpatient DBT are highly structured individual or group skills training, individual psychotherapy (addressing motivation and skills strengthening), and telephone contact with the individual therapist (addressing application of coping skills). Third, a consultation team meeting focused specifically on keeping therapists motivated and providing effective treatment was added as a fourth treatment component.

2. Treatment Stages And Goals

DBT is designed to treat patients at all levels of severity and complexity of disorders. In stage 1, DBT focuses on patient behaviors that are out of control. The treatment targets in stage 1 are: (a) reducing high-risk suicidal behaviors (parasuicide acts, including suicide attempts, high-risk suicidal ideation, plans, and threats); (b) reducing client and therapist behaviors that interfere with the therapy (e.g., missing, coming late to sessions, telephoning at unreasonable hours or otherwise pushing a therapist’s limits, not returning phone calls); (c) reducing behavioral patterns serious enough to substantially interfere with any chance of a reasonable quality of life (e.g., depression and other axis I disorders, homelessness, chronically losing relationships or jobs); and (d) acquisition of sufficient life skills to meet client goals (skills in emotion regulation, interpersonal effectiveness, distress tolerance, self-management, as well as mindfulness). Subsequent to achieving behavioral control, it becomes possible to work on other important goals including (e) focusing on the ability to experience emotions without trauma (stage 2); (f ) enhancing self-respect; (g) addressing problematic patterns in living that interfere with goals (stage 3); and (h) resolving feelings of incompleteness and enhancing the capacity for joy (stage 4). In sum, the orientation of the treatment is to first get action under control, then to help the patient to feel better, to resolve problems in living and residual disorder, and to find joy and, for some, a sense of transcendence.

With respect to each goal in treatment, the task of the therapist is first (and many times thereafter) to elicit the client’s collaboration in working on the relevant behavior, then to apply the appropriate treatment strategies described below. Treatment in DBT is oriented to current in-session behaviors or problems that have surfaced since the last session, with suicide attempts and other intentional self-injurious acts and life-threatening suicidal ideation, planning, and urges taking precedence over all other topics. Because therapeutic change is usually not linear, progress through the hierarchy of goals is an iterative process.

3. Treatment Strategies

DBT addresses all problematic client behaviors and therapy situations in a systematic, problem solving manner. The context of these analyses and of this solution-oriented approach is that of validation of the client’s experiences, especially as they relate to the individual’s vulnerabilities and sense of desperation. In contrast to many behavioral approaches, at least as described in print, DBT places great emphasis on the therapeutic relationship. In times of crisis, when all else fails, DBT uses the relationship itself to keep the client alive.

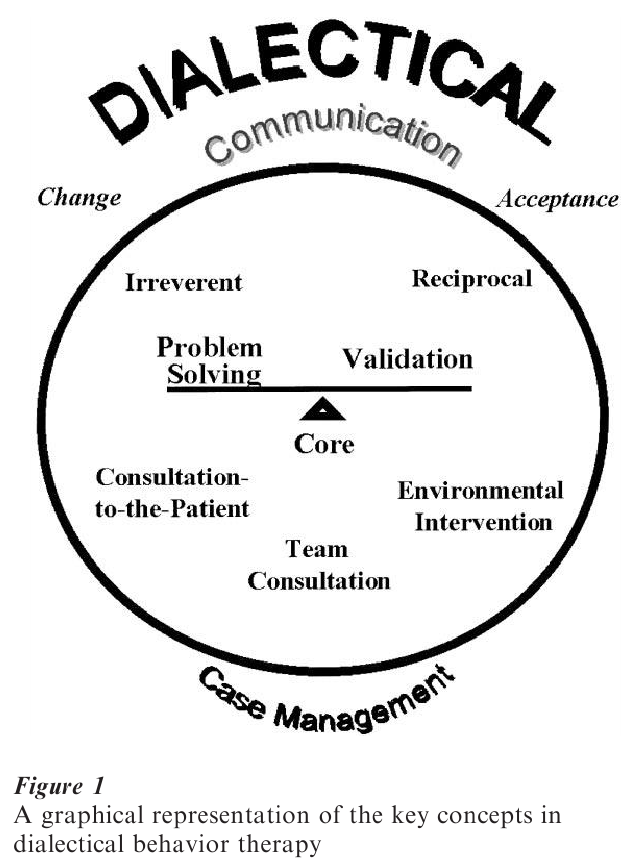

Treatment strategies in DBT are divided into four sets: (a) dialectical strategies, (b) core strategies (validation and problem solving), (c) communication strategies (irreverent and reciprocal communication), and (d) case management strategies (consultation to the patient, environmental intervention, supervision consultation with therapists). There are, as well, a number of specific behavioral treatment protocols covering suicidal behavior, crisis management, therapy-interfering behavior and compliance issues, relationship problem solving, and ancillary treatment issues, including psychotropic medication management. These are more fully described in the treatment manuals (Linehan 1993a, 1993b). Their relationships to each other, and to acceptance and change, are represented in Fig. 1.

Dialectical strategies are woven throughout all treatment interactions. The primary dialectical strategy is the balanced therapeutic stance, the constant attention to combining acceptance with change. The goal is to bring out the opposites, both in therapy and the client’s life, and to provide conditions for synthesis. Strategies include extensive use of stories, metaphor, and paradox; the therapeutic use of ambiguity; viewing therapy, and indeed all of reality, as constant change; cognitive challenging and restructuring techniques; and reinforcement for use of intuitive, nonrational knowledge bases.

Core strategies consist of the balanced application of problem solving and validation strategies. Problem solving is a two-stage process involving, first, an analysis and acceptance of the problem at hand, and second, an attempt to generate, evaluate, and implement alternative solutions which might have been made or could be made in the future in similar problematic situations. Analysis of the client’s problem behaviors, including dysfunctional actions, emotions, physiological responses, and thought processes, requires detailed analyses of the chains of events (both responses of the individual and events in the environment) leading up to the problematic responses. This analysis is repeated for every instance of targeted problem behaviors until both therapist and client achieve an understanding of the response patterns involved. The second stage, which is actually interwoven with the first, requires the generation of new, more skillful responses, as well as an analysis of the individual’s capabilities and motivation to actually engage in the new behaviors. This process leads into application of change procedures drawn primarily from innovations in behavior therapy and from the cognitive modification techniques of rational-emotive therapy. Management of contingencies in the therapeutic relationship, training in behavioral skills, exposure techniques with response prevention, and cognitive restructuring anchor the behavioral change end of the primary dialectic in DBT.

Validation, which balances and keeps problem solving moving forward, requires the therapist to search for, recognize, and reflect the validity, or sensibility, of the individual’s current patterns of behavior. Validation is required in every interaction and is used at any one of six levels: Level 1, listening to the client with interest; Level 2, reflection, paraphrasing, summarizing; Level 3, articulating or ‘mindreading’ that which is unstated, such as fears of admitting emotions or thoughts, but without pushing the interpretation on the client; Level 4, validating the client’s experience in terms of past experiences or in terms of a disease or brain disorder model; Level 5, validating the client in terms of present and normal functioning (e.g., high emotional arousal disorganizes cognitive functioning in all people); and Level 6, radical genuineness with clients—treating the client–therapist relationship as an authentic and ‘real’ relationship. In line with this latter prescription of the treatment, the therapist does not treat clients as fragile or unable to solve problems.

In DBT, the therapist balances two communication strategies which represent rather different interpersonal styles. The modal style is the reciprocal strategy, which includes responsiveness to the client’s agenda and wishes, warmth, and self-disclosure of both personal information that might be useful to the client as well as immediate reactions to the client’s behavior. Reciprocity is balanced by an irreverent communication style: a matter-of-fact or at times slightly outrageous or humorous attitude where the therapist takes the client’s underlying assumptions or unnoticed implications of the client’s behavior and maximizes or minimizes them, in either an unemotional or overemotional manner to make a point the client might not have considered before. Irreverence ‘jumps track,’ so to speak, from the client’s current pattern of response, thought, or emotion.

There are three strategies designed to guide each therapist during interactions with individuals outside the therapy dyad (case management strategies). The consultation supervision strategy requires that each DBT therapist meet regularly with a supervisor or consultation team. The idea here is that severely suicidal individuals should not be treated alone. The consultant-to-the-client strategy is the application of the principle that the DBT therapist teaches the client how to interact effectively with the client’s environment, rather than teaching the environment how to interact with the client. When absolutely necessary, however, the therapist actively intervenes in the environment to protect the client or to modify situations that the client does not have the power to influence.

4. Research

Data suggest that with severely disordered patients meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder, DBT is more effective than treatments applied as usual in the community in reducing targeted problem behaviors (suicide attempts, substance abuse, treatment dropout, use of psychiatric in-patient hospitalization) and improving both general and social functioning (Linehan et al. 1991, 1994). With a less severe population of BPD patients, DBT appears to produce specific improvements in suicidal ideation, depression, and hopelessness, even when compared to a treatment-as-usual condition that also produces clinically significant changes in depression (Koons et al. 2001). Where follow-up data are available, it appears that these results may hold up to one year post-treatment (Linehan et al. 1993). These findings are generally replicated by both randomized clinical trials with better experimental control as well as quasiexperimental effectiveness studies. From available evidence, it appears that DBT is a step toward more effective treatment for multidisordered patients, particularly those with suicidal behavior.

Bibliography:

- Bohus M, Haaf B, Stiglmayr C, Pohl U, Bohme R, Linehan M in press Evaluation of inpatient dialectical-behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder—a prospective study. Behaviour Research and Therapy

- Koerner K, Linehan M M in press Research on dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America

- Koons C R, Robins C J, Bishop G K, Morse J Q, Tweed J L, Lynch T R, Gonzalez A M, Butterfield M I, Bastian L A 2000 Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy 32: 371–90

- Linehan M M 1993a Cognitive Behavioral Therapy of Borderline Personality Disorder. Guilford Press, New York

- Linehan M M 1993b Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder. Guilford Press, New York

- Linehan M M 1997 Behavioral treatments of suicidal behaviors: Definitional obfuscation and treatment outcomes. In: Stoff D M, Mann J J (eds.) Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences: Vol. 836. The Neurobiology of Suicide: From the Bench to the Clinic. New York Academy of Sciences, New York, pp. 302–28

- Linehan M M 1998 An illustration of dialectical behavior therapy. In Session: Psychotherapy in Practice 4: 21–44

- Linehan M M, Armstrong H E, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard H L 1991 Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 48: 1060–4

- Linehan M M, Heard H L, Armstrong H E 1993 Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 50: 971–4

- Linehan M M, Tutek D A, Heard H L, Armstrong H E 1994 Interpersonal outcome of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically suicidal borderline patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 151: 1771–6

- Miller A, Rathus J H, Linehan M M, Wetzler S, Leigh E 1997 Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health 3: 78–86