Sample Developmental Dyslexia Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Developmental dyslexia can be characterized as a specific problem with reading and spelling that cannot be accounted for by low intelligence, poor educational opportunities, or obvious sensory or neurological damage. Children with developmental dyslexia often appear to have good spoken language skills and extensive vocabularies. Accordingly, the first theories of developmental dyslexia postulated underlying deficits in visual processing (‘word blindness’). Recent evidence from developmental psychology, genetics, and brain imaging increasingly suggests, however, that the central deficit in developmental dyslexia is a linguistic one. In particular, dyslexic children appear to have difficulties in the accurate specification of phonology when storing lexical representations of speech.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. The Normal Development Of Lexical Representations

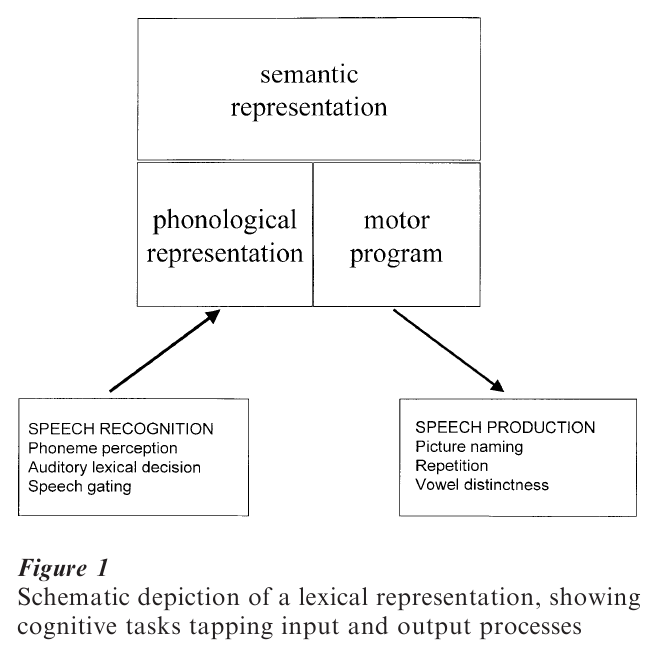

A schematic view of a lexical representation is shown in Fig. 1. Researchers in child phonology have shown that, in the normal course of development, the phonological aspects of children’s lexical representations become increasingly segmental and distinctly specified in terms of phonetic features. When vocabulary size is small, there is no need to represent words in a systematic or detailed manner, and so early word representations are thought to encode fairly global phonological characteristics (e.g., Jusczyk 1993). As vocabulary grows, these holistic representations are gradually restructured, so that smaller segments of sound are represented (Metsala and Walley 1998). Developmentally, children appear to first represent syllables (a word like wigwam has two syllables), then onsets and rimes (the onset in a syllable corresponds to the sound/s before the vowel, the rime corresponds to the vowel and any subsequent sounds, e.g., p – it; scr – ew), and ultimately, phonemes (phonemes are the smallest units of sound that change word meaning, e.g., pit differs from sit, pot, and pin by the initial, medial, and final phonemes, respectively). According to this ‘emergent’ view of segmental representation (Metsala and Walley 1998), the phoneme is not an integral aspect of speech representation and processing from infancy onwards (as was once thought), but rather emerges as a representational unit via spoken language experience. The degree to which segmental representation has taken place is in turn thought to determine how easily the child will become phonologically ‘aware’ and will learn to read and write.

Dyslexic children appear to have specific difficulties in the representation of segmental phonology. Most of the evidence for this ‘phonological deficit’ has come from ‘phonological awareness’ tasks, in which children are asked to make judgements about shared phonology or to manipulate phonology (e.g., the rhyme oddity task, in which the child is asked to distinguish the odd word out from a triple like man, pat, fan, and the phoneme substitution task, in which the child is asked to substitute the initial phonemes in words, so that Bob Dylan becomes Dob Bylan). A large number of studies carried out in many languages has shown that dyslexic children perform poorly in such phonological awareness tasks (see Goswami in press, for review). Importantly, such deficits are found even when dyslexic children’s performance is compared to that of younger children who are reading and spelling at the same level as them (the methodologically important reading le el match research design, which holds reading level constant rather than chronological age and thus gives a mental age advantage to the dyslexic children). A phonological deficit seems to characterize dyslexia across languages. Whether the child is learning to read a nontransparent orthography like English, or a transparent orthography like German, phonological awareness deficits are consistently found. This suggests that an important causal factor in dyslexia is an underlying difficulty in developing segmentally well-specified lexical representations of speech.

2. The Abnormal Development Of Phonological Representations In Dyslexia

The cognitive profiles of developmental dyslexics show fairly specific linguistic deficits that are related to phonology rather than semantics. For example, developmental dyslexics have poor phonological memory skills. They find it difficult to remember verbal sequences, and they show poor performance on standardized tests of phonological memory (such as repeating nonsense words like ballop and thickery). Repeating nonsense (novel) word forms requires the child to set up new phonological representations. Developmental dyslexics are also slower to recognize familiar words on the basis of acoustic input. For example, they require more acoustic-phonetic information than age-matched controls to recognize familiar words in speech gating tasks, in which incremental segments of speech from word-onset are presented through headphones. On the output side, developmental dyslexics show deficits in fine-grained measures of speech production such as the distinctness of vowel articulation. They also show problems in confrontation naming tasks (in which simple pictures must be named on demand), even though they are very familiar with the items in the pictures. Their problems are particularly marked when the familiar names are long and of low frequency, and thus correspond to phonological forms that have been encountered less frequently and that also require the accurate specification of more phonological segments. Developmental dyslexics find rapid ‘automatized’ speeded naming tasks difficult. These tasks require the child to name familiar items presented in lists (such as digits) as quickly as possible, thereby accessing and outputting what should be well-practiced and so well-specified phonological forms (‘nine, two, five,…’).

3. Auditory Processing Problems

Studies that have attempted to uncover basic auditory processing deficits to explain this apparently selective difficulty in representing phonological forms in memory have so far produced mixed results. Typically, a basic processing task will show dramatic impairments for some dyslexic children, and no apparent impairment for others, despite extremely careful subject selection. Thus, some dyslexic children have great difficulty with ‘minimal pairs’ tasks that require the discrimination of similar-sounding words (e.g., smack–snack), yet others do not (Adlard and Hazan 1998). Some dyslexic children find phoneme categorization and repetition tasks very difficult (e.g., discriminating between or repeating b and d ), and others do not (e.g., Manis et al. 1997). Some dyslexic children find temporal order judgements very difficult. Typically, such tasks require them to decide whether a high tone preceded a low tone or vice versa. Accordingly, it has been proposed that dyslexia is caused by temporal processing deficits (e.g., Tallal 1980), but this view is quite controversial. For example, Mody et al. (1997) have shown that dyslexic children who find it difficult to discriminate phonemes like ba/da show no deficit with a nonspeech analogue task that makes the same temporal processing demands (sine wave speech). Thus far, most auditory processing deficits that have been found appear to be specific to linguistic stimuli. However, the lack of uniformity across subjects is puzzling. One possibility is that the primary basic processing difficulty has not yet been discovered. A second is that the difficulty lies not in perception per se, but in representing the segments that can be detected in the input, as discussed above. A third is that sensory deficits in basic auditory processing and phonological deficits are not causally related, but arise from the dysfunction of a neural system common to both (Eden and Zeffiro 1998). Finally, it is logically possible that there may be a variety of causes of dyslexia, with some children’s primary problems lying outside the auditory realm.

4. Phonological Processing Deficits In Dyslexia: Brain Imaging Studies

Nevertheless, evidence from brain imaging work is consistent with the view that the key difficulty in dyslexia is a weakness in the representation of phonological information. The phonological processing system spans a number of cortical and subcortical regions in the brain, including frontal, temporal, and parietal cortex. Studies of aphasia long ago revealed the importance of Broca’s area (frontal cortex) and Wernicke’s area (posterior superior temporal gyrus) for the motor production and receptive aspects of speech, respectively, and the lateralization of language-related processes to the left hemisphere is equally well documented.

Interpretation of functional neuroimaging studies of dyslexia is complicated by the fact that only adult developmental dyslexics can be scanned, which means that the brain’s compensatory responses to any initial disorder may account for some of the patterns of task related activity that are found. Nevertheless, despite seemingly inconsistent results in early studies, localization of phonological mechanisms in the temporoparietal junction and abnormalities in activation surrounding this junction in adult developmental dyslexics during phonological processing tasks have been documented by a number of research groups (see Eden and Zeffiro 1998 for review). When performing tasks like rhyme judgement, rhyme detection, and word and nonsense word reading, dyslexic subjects show reduced activation in temporal and parietal regions, particularly within the left hemisphere.

5. Genetics Of Developmental Dyslexia

The heritability of dyslexia has been demonstrated by a number of family and twin studies (e.g., Gayan and Olson 1997). More recently, linkage studies have been used to try to determine where in the human genome the critical genes for dyslexia are located. The most promising findings so far concern the short arm of chromosome 6, and sites on chromosome 15 (e.g., Grigorenko et al. 1997). These studies depend on definitions of the dyslexic phenotype that are based on deficits in phonological awareness tasks and single or nonsense word reading. Thus there is evidence that individual differences in phonological processing are to some extent heritable. Of course, there cannot be a ‘gene’ for dyslexia in the sense that there is a gene for eye color, as reading is a culturally determined activity. Individuals at genetic risk for dyslexia who develop in a favorable early environment as far as reading is concerned (for example, children who have carers who stimulate their linguistic awareness via language games, nursery rhymes, and so on, and who read books to them and model and encourage literacy activities by reading and writing extensively themselves) may be able to compensate to some extent for their genetic predisposition to dyslexia. Other individuals with a lower degree of risk but relatively adverse early environments may be more handicapped.

6. Developmental Dyslexia Across Languages

As noted earlier, the degree to which the segmental representation of phonology has taken place is thought to determine how easily the child will become phonologically ‘aware’ and will learn to read and write. Phonological awareness is usually defined as the ability to recognize and manipulate subsyllabic units in spoken words. It has been shown to be an important predictor of reading and spelling progress in a vast number of studies of normally developing children in many languages, and follows the developmental sequence syllable–onset rime–phoneme across all the alphabetic languages so far studied (Goswami in press). Nevertheless, it is also the case that learning to read itself affects the representation of segmental phonology. In particular, attainment of the final developmental stage of full phonemic representation is highly dependent on being taught to read and write an alphabetic language (see Goswami and Bryant 1990 for a review).

For example, adults who are illiterate show the same difficulties with phonological awareness tasks at the phoneme level as prereading children, and Japanese children (who learn to read a syllabary) show relatively poor phoneme level performance in comparison to American children.

Given the close relationship between the development of phonemic awareness and learning to read and write, the difficulties faced by developmental dyslexics would be expected to vary to some degree with linguistic transparency, even if the underlying problem in all languages concerns phonological representation. This is in fact the case. Dyslexic children who are learning to read and spell transparent orthographies like German show the confrontation naming deficit characteristic of English dyslexic children, suggesting that their phonological representations of speech are compromised. However, they do not show accuracy deficits in nonsense word reading tasks, although they do show marked speed deficits (e.g., Wimmer 1993). When nonsense words are carefully matched across languages, German dyslexic children are much better at reading nonsense words than English children (Landerl et al. 1997). This presumably reflects the consistency of grapheme–phoneme relations in German compared to English. The German child, even the child with a linguistic difficulty, is learning a less variable orthographic code.

7. Subtypes Of Developmental Dyslexia?

Some researchers have argued strongly for two subtypes of developmental dyslexia: ‘surface’ dyslexia and ‘phonological’ dyslexia (but see Oliver et al. in press). Phonological dyslexics are thought to have problems in assembling sublexical phonology (reading using abstract spelling-to-sound ‘rules’). Surface dyslexics are thought to have problems in using stored lexical knowledge to pronounce words (they seem to have difficulty in directly addressing orthographic representations). This ‘double dissociation’ model of developmental dyslexia has been drawn from patterns of adult pathology (the ‘acquired’ dyslexias).

The subtyping argument has depended critically on the use of regression procedures, in which performance relationships between the use of lexical and sublexical phonology characteristic of normal children are used to derive confidence limits for assessing the same performance relationships in dyslexic populations. These regression procedures typically depend on the use of chronological age-matched normal readers. As processing tradeoffs between the reliance on lexical and sublexical phonology may depend on the overall level of word recognition that the child has attained, reading le el matched controls are more appropriate. Stanovich et al. (1997) demonstrate clearly that when reading level matched controls are used to define processing tradeoffs, then almost no ‘surface dyslexic’ children are found, even in the original samples used to support the notion of subtypes of developmental dyslexia. They conclude that the ‘surface’ dyslexic profile arises from a milder form of phonological deficit accompanied by exceptionally inadequate reading experience.

8. Towards A Phenotype Of Dyslexia

Neurodevelopmental disorders are not discrete syndromes, but most typically have a graded character. They are also seldom highly specific, and rarely involve a single deficit. Although a difficulty in representing segmental phonology appears to be the core symptom of developmental dyslexia, many researchers have noted a number of associated deficits that more or less frequently accompany the phonological deficit. For example, dyslexic children can be clumsy, they can have attentional problems, they may display mild cerebellar signs such as slow motor tapping, and they may have subtle abnormalities in visual processing such as poor motion processing when visual stimuli are of low contrast and low luminance. At present, the most widely accepted phenotype of developmental dyslexia depends on deficits in performance on a battery of cognitive tasks that tap the integrity of the child’s phonological representations of speech. This battery most typically includes phonological awareness tasks, single word and nonsense word reading tasks, and rapid ‘automatized’ naming tasks. Developmental dyslexia is thus currently best conceived as a subtle linguistic deficit that involves an impairment in the representation of the phonological segments of speech in the brain.

Bibliography:

- Adlard A, Hazan V 1998 Speech perception in children with specific reading difficulties (dyslexia). Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 51A: 153–77

- Eden G F, Zeffiro T A 1998 Neural systems affected in developmental dyslexia revealed by functional neuroimaging. Neuron 21: 279–82

- Gayan J, Olson R K 1997 Common and specific genetic effects on reading measures. Behavioral Genetics 27: 589

- Goswami U in press Phonological representations, reading development and dyslexia: Towards a cross-linguistic theoretical framework. Dyslexia

- Goswami U, Bryant P E 1990 Phonological Skills and Learning to Read. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

- Grigorenko E L, Wood F B, Meyer M S, Hart L A, Speed W C, Shuster A, Pauls D L 1997 Susceptibility loci for distinct components of developmental dyslexia on chromosomes 6 and 15. American Journal of Human Genetics 60: 27–39

- Jusczyk P W 1993 From general to language-specific capacities: The WRAPSA model of how speech perception develops. Journal of Phonetics 21: 3–28

- Landerl K, Wimmer H, Frith U 1997 The impact of orthographic consistency on dyslexia: A German–English comparison. Cognition 63: 315–34

- Manis F R, McBride-Chang C, Seidenberg M S, Keating P, Doi L M, Munsun B, Petersen A 1997 Are speech perception deficits associated with developmental dyslexia? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 66: 211–35

- Metsala J L, Walley A C 1998 Spoken vocabulary growth and the segmental restructuring of lexical representations: Precursors to phonemic awareness and early reading ability. In: Metsala J L, Ehri L C (eds.) Word Recognition in Beginning Literacy. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 89–120

- Mody M, Studdert-Kennedy M, Brady S 1997 Speech perception deficits in poor readers: Auditory processing or phonological coding? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 64: 199–231

- Oliver A, Johnson M H, Karmiloff-Smith A, Pennington B in press Deviations in the emergence of representations: A neuroconstructivist framework for analysing developmental disorders. Developmental Science

- Stanovich K E, Siegal L S, Gottardo A 1997 Converging evidence for phonological and surface subtypes of reading disability. Journal of Educational Psychology 89: 114–27

- Tallal P 1980 Auditory temporal perception, phonics and reading disabilities in children. Brain and Language 9: 182–98

- Wimmer H 1993 Characteristics of developmental dyslexia in a regular writing system. Applied Psycholinguistics 14: 1–33