View sample mental health research paper on mental health and substance abuse. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Introduction

An Increasing Burden Of Disease Requiring An Effective Service Response

Around the world, it is estimated that at least 450 million people experience mental, neurological, or substance use disorders, including about 76 million experiencing alcohol use disorders and approximately 15 million, drug use disorders. One person in every four has been affected by a mental disorder at some stage during their life.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The disease burden of these disorders is enormous (Figure 1 and Table 1), thus creating a devastating social and economic impact for individuals, families, and governments. In the year 2002 mental and substance use disorders accounted for 13% of the global burden of disease (WHO, 2004).

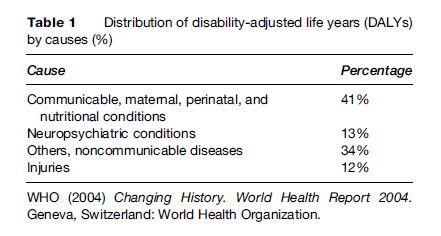

Although the burden is high, only a small proportion of people receive effective treatment and care (Table 2). A recent WHO study in 14 countries (Kohn et al., 2004) has shown just how extensive is the treatment gap for mental health and substance abuse disorders. In high-income countries 35.5% to 50.3% of people suffering from serious mental health and substance use disorders did not receive treatment within the prior year. The corresponding range for low-income countries was even higher with 76% to 85% not receiving treatment. To reduce this treatment gap and the overall health burden, it is essential that services for mental, neurological and substance abuse disorders are put in place.

Relationship Between Mental And Physical Disorders

Mental health is as important as physical health to the overall well-being of individuals. The data to substantiate this important relationship are becoming increasingly evident from studies examining comorbidity between mental and physical health problems.

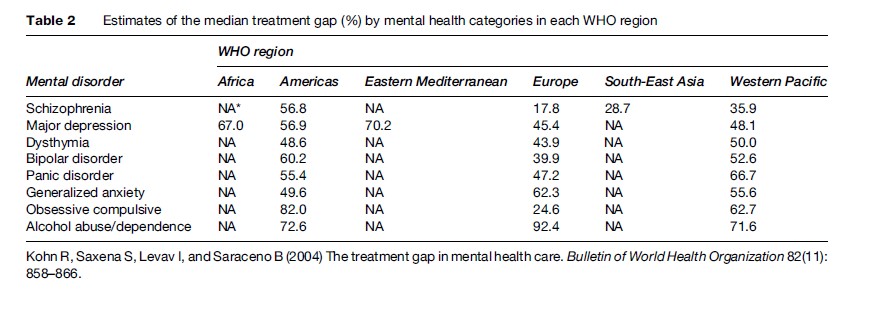

Mental health and substance use disorders are often comorbid with many physical health problems such as cancer, HIV/AIDS, diabetes, tuberculosis, hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and heart disease among others. For example, a review of studies (Figure 2) reports that the 1-year prevalence of depression in people living with HIV/ AIDS can be as high as 44%; and as high as 33% in those people who have cancer. This is compared with the estimated 10% prevalence rates in the general population (Saraceno et al., 2003). In addition, injecting drug use is one of the leading modes of HIV in the world (UNAIDS, 2006). In the United States in 1999 injecting drug users accounted for 18% of the reported HIV cases classified by a specific risk and at least 36% of all reported AIDS cases (CDC, 2001). The disability of individual sufferers and the burden on families increase with the number of comorbid conditions experienced. In addition, the presence of comorbidity has implications for the identification, treatment, and rehabilitation of affected individuals. For example, knowing that someone has diabetes or another relevant condition should lead the health provider to conduct a mental health assessment to identify and treat any (previously unidentified) mental disorder. Finally, because mental disorders such as depression significantly reduce treatment compliance, treatment for the mental disorder can lead to greatly improved outcomes for the ‘physical’ health problem.

For overall health outcomes to be improved on the population level, interventions for mental health and substance use disorders must be accessible to those in need and have to be provided through services in general health care. Providers of these services should be able to identify mental and substance use disorders, understand the links between mental and physical disorders, and have the skills to address both dimensions for any one health problem.

Link Between Poverty And Mental Health

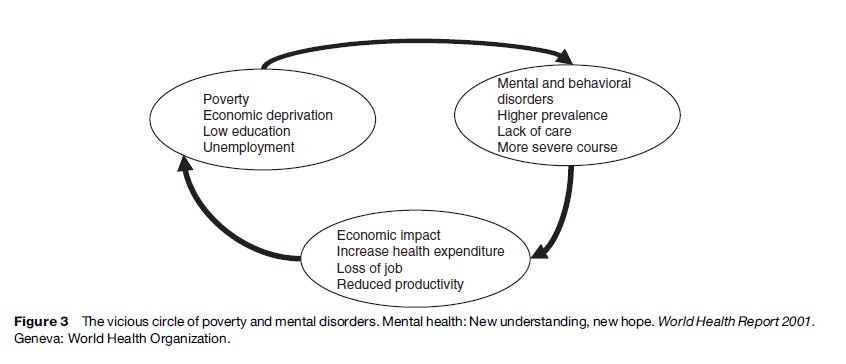

Studies over the last 20 years indicate a close reciprocal association between poverty and mental ill-health (Patel, 2001). Not only can poverty increase the risk of developing a mental disorder but having a mental disorder can be an important factor leading people into poverty (Figure 3). Common mental disorders are about twice as frequent among the poor as among the rich (Patel et al., 1999). In relation to severe mental disorders, and schizophrenia specifically, data from developed countries show that people with the lowest socioeconomic status (SES) have 8 times more relative risk for schizophrenia than those of the highest SES (Saraceno and Barbui, 1997).

It is therefore crucial that services are widely accessible to people with mental disorders including those living in poverty. The provision of effective treatment and care can help people to recover and ‘exit’ the poverty in which they are living; however, this can only be achieved if services are accessible in terms of both physical reach and affordability. Providing ineffective treatment and care or services that go beyond the means of the individual concerned can act to drive them further into poverty. It is crucial that services are comprehensive and meet the variety of psychosocial needs of people with mental illness which are also required to bring them out of poverty (employment, education, social services).

Stigma And Human Rights Violations

People with mental and substance use disorders are stigmatized, excluded from society, and subject to human rights abuses. The stigma and misconceptions associated with mental disorders mean that people are marginalized and ostracized from society. People with mental disorders are often assumed to be lazy, weak, unintelligent, and incapable of making decisions, and these are common reasons why they are denied employment and education opportunities. In many countries people do not have access to the basic mental health care and treatment they require. Often the only care available is in psychiatric institutions which are themselves associated with gross human rights violations. People in these institutions are often exposed to inhuman and degrading living conditions, with little or no access to proper clothes, clean water, and food. They are also exposed to harmful practices such as the abusive use of seclusion and restraint.

Even when the physical environment of a mental health facility is adequate and clean with basic needs being provided for, neglect remains a key feature of institutional care. Many people receive no form of stimulation for months and even years. This aimlessness, inactivity, and social isolation is inhuman and degrading.

Services for mental health and substance abuse need to be respectful of human rights and the dignity of people with mental disorders and conducive to recovery. The treatment, care, and support provided must be comprehensive enough to meet the variety of psychosocial needs of those with mental illness that are required for re-integration into the community.

Mental Health Service Organization

In many communities in countries all over the world, people are not able to access services and many of the available services are of poor quality. In low-income countries, the typical pattern of services is to have one or more psychiatric institutions based in urban areas and some informal community services provided by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), traditional healers, spiritual healers, or religious groups. In middle and high-income countries, it is not uncommon to find a predominance of institutional care services, although these countries have to varying degrees implemented a formal system of care involving community services, hospitals, and primary care.

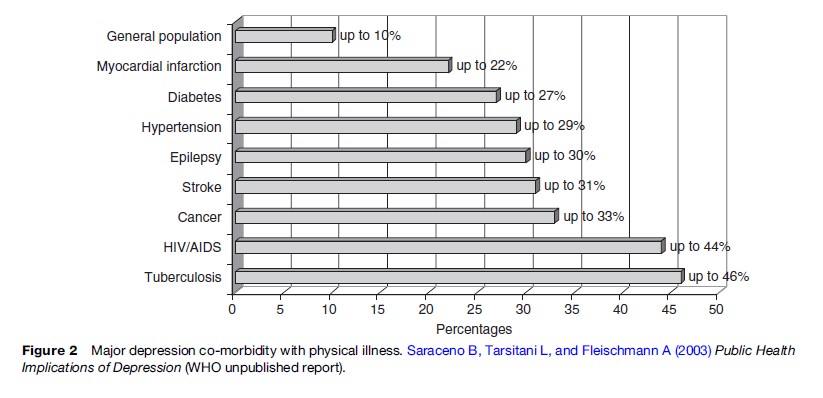

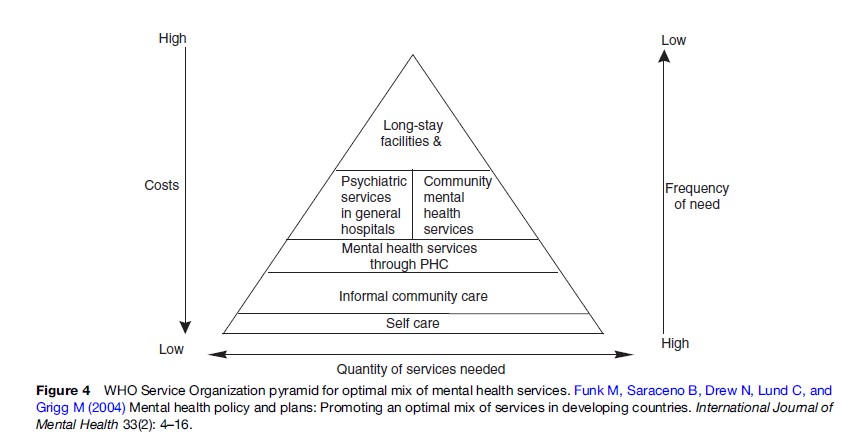

WHO has developed a pyramid framework (Figure 4) which conceptualizes an optimal mix of services for mental health. It reinforces the idea that no single service will meet all needs, and that what is needed is an optimal mix of a range of services (Funk et al., 2004).

According to this framework, and starting at the top of the pyramid, the least numerous services ought to be mental hospitals and specialist services, for example, psychiatric institutions and long-term residential treatment for alcohol and drug dependence. The second layer includes formal community mental health services (day care centers, outreach services, crisis services, and methadone clinics for opioid dependence patients) and general hospital-based services (psychiatric and substance abuse units in general hospitals). The third represents mental health services provided through primary health care. The fourth layer represents informal community mental health services, for example, traditional healers, village leaders, schoolteachers, and informal groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous. The fifth and final layer involves self-care management, that is, helping people to learn how to take care of themselves. Each of these levels is described in more detail in later sections of this research paper, including the strengths of and considerations for delivering care at that level.

Long-Stay Facilities

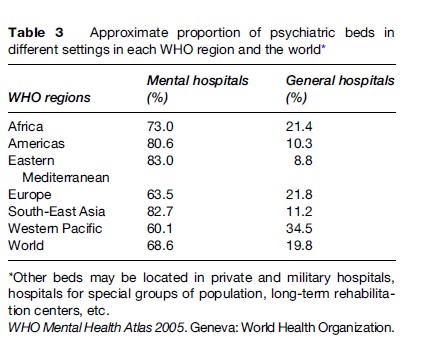

Psychiatric institutions and specialist services present the highest cost, yet are the least frequently needed service. Psychiatric institutions in both the developing and the developed world have a history of serious human rights violations. Clinical outcomes tend to be poor as a result of poor treatment and care practices and lack of rehabilitative activities in these hospitals. Where they exist, they consume most of the available specialist mental health resources and budget of the country, and this acts as a serious barrier to developing alternative or additional services.

Because of the high costs, often poor clinical outcomes, and human rights violations, mental hospitals represent the least desirable use of scarce financial resources available for mental health services (Table 3). Specialist residential services for alcohol and drug dependence may be needed for particular groups of clients and for most severe forms of substance use disorders, but their potential impact on population health is limited.

A very important recommendation of WHO is to replace psychiatric institutions by a network of services in the community. Essentially this means embarking on a process of deinstitutionalization – a planned and gradual transition from a predominantly institutionally based service model to a model that provides treatment and care through community services, general hospitals, and primary health care.

The failure of many countries to make sure that these services are in place when psychiatric institutions close has led to problems of marginalization and homelessness.

Formal Community Mental Health Services

Within this category formal community mental health services refer to day centers, rehabilitation services, hospital diversion programs, mobile crisis teams, therapeutic and residential supervised services, and home help and support services that are based in the community.

Strengths

Providing community services has been shown to result in better physical health and mental health outcomes and better quality of life than treatment provided in institutions. In addition, shifting patients from mental hospitals to care in the community has been shown to be cost effective and ensures a better promotion and protection of the rights of people with mental and substance use disorders.

Considerations

First, the development of community services can require a vast and highly skilled group of professionals, thereby limiting the capacity of many countries to immediately put in place an extensive network of services. As a result, planners need to prioritize the development of some services, while developing others in a phased manner over time.

A second consideration in prioritizing the development of some community services over others is to identify the existing resources in the country. For example, in some countries fewer services such as halfway houses or group homes may be needed because of the availability of good family support. In situations like these planners need to acknowledge and actively support the efforts of families in caring for persons with mental disorders, rather than working to build new group homes. Finally, community mental health services work best when they have strong links with general hospitals, primary health-care services, and informal community services.

Mental Health Services In General Hospitals

Another important WHO recommendation is to develop mental health services in general hospital settings. A common example of a service is a health unit within the general hospital itself, but this category also refers to other services such as consultation liaison services provided in the hospital. Specialist mental health professionals or general health workers with specialist training in psychiatry generally deliver these types of services.

Strengths

One of the most important advantages of this type of service is that it provides a setting to manage acute episodes of mental disorders. Second, there is the opportunity to simultaneously obtain medical treatment for comorbid physical illnesses, and it also allows access to specialist investigations and treatment. Third, the hospital can become a base for undergraduate and postgraduate teaching and training for many different types of health professionals, from physicians and nurses to psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers.

Considerations

It is important to keep in mind some of the limitations of these services. Although general hospital services (short-stay wards and consultation-liaison services to other medical departments) can manage acute episodes of mental disorders quite well, they do not provide a solution for people with chronic disorders who end up in the admission–discharge–admission cycle (revolving door syndrome) unless backed up by comprehensive primary health-care services or community services. Second, their location generally, in district headquarters and big cities, can create access problems especially in developing countries which lack good, reliable, and cheap public transportation services.

Mental Health Services In Primary Health Care

Integration of mental health care into primary health care has been a fundamental WHO policy since the Alma Ata Declaration in 1978 and continues to be so. Services referred to in this category refer to mental health care and promotional and preventive activities conducted by health workers at the first level of formal health care; for example, general practitioners, nurses, and other staff providing assessment, treatment, and referral services for mental and substance use disorders. Early identification and management of hazardous and harmful drinking is a good example of an activity at the level of primary health care that, if widely implemented, can have a significant effect on population levels of alcohol-related problems (Whitlock et al., 2004).

Strengths

As discussed in relation to general hospital care, providing treatment for mental and substance use disorders in primary health care improves access to mental health services and specialist services for substance use disorders as well as to treatment of comorbid physical conditions. Additionally, stigma is reduced – and acceptability for users improved – when seeking mental health care from a primary health-care provider. In terms of clinical outcomes it has been found that, for most common mental disorders, primary health care can deliver good care and certainly better care than that provided in psychiatric hospitals. From a management perspective, integrating health services for mental and substance use disorders into primary health care can be an important solution to addressing human resource shortages in the delivery of mental health interventions.

Considerations

Integration requires a lot of careful planning and there are likely to be several issues and challenges that will need to be addressed. For example, integration into primary health care requires investment in the training of staff to detect and treat mental and substance use disorders. Ongoing supervision is also of utmost importance, and mental health professionals should be available to primary care staff, as required, to give advice as well as guidance on management and treatment of people with mental and substance use disorders.

The issue of availability of time needs to be addressed. In many countries primary health-care staff are overburdened with work as they are expected to deliver multiple health-care programs. Governments cannot ignore the need to increase the numbers of primary health-care staff who are either partially or entirely devoted to mental health care.

Informal Community Mental Health Services

These refer to services provided in the community but that do not form part of the formal health and welfare system. These may include, but are not limited to, services delivered by traditional healers and professionals in other sectors (social and village/community workers, teachers, police) as well as services delivered by nonprofessional organizations or lay persons (such as consumer and family associations, advocacy groups, and NGOs).

Strengths

In many countries, informal community services are the first point of contact for a majority of persons with mental and substance use disorders and sometimes they represent the only service available to them. These services can play an important supportive role in improving outcomes for persons with mental disorders. They can help maintain community integration and provide a supportive network which reduces the risk of relapse. These services enjoy high acceptability and there are few barriers to access as they are nearly always based in the community. The high degree of community acceptability also reduces the likelihood of stigma associated with using these services.

Considerations

Informal community mental health services should not form the core of mental health service provision and countries would be ill-advised to depend solely on these services. Rather they form a useful complement to formal mental health services and can form useful alliances with such services.

There is also the issue of the quality of these services given that many currently fall out of the ambit of regulation in many countries. Indeed, it is not uncommon to find services providing either ineffective or inappropriate and harmful care. In many instances, human rights violations are committed.

Self-Care

The level of self-care refers to individuals’ knowledge and skills to manage their mental health disorders on their own or with the help of family and friends.

Strengths

The service level of self-care acknowledges the role and autonomy of individuals (and families) to deal with their own psychological or mental health problems given access to the right information and guidance. Low-cost resources – for example, written materials or radio programs – can be used to promote self-care in the community.

Considerations

Problems related to mental health and substance use vary widely in complexity and severity, and medical and other professional expertise are essential for some of the more severe and complex cases. However, for all cases, the provision of information and support goes a long way in helping people take control of their illness and reduce their dependence on the health system.

Key Principles For Organizing Services

Even if the ‘ideal’ service organization model, as depicted in Figure 4, is adopted, it would not result in optimal treatment and care for persons with mental and substance use disorders unless a number of key ‘principles’ for organizing services are respected. These include the need to have services and care that promote accessibility, comprehensiveness, effectiveness, continuity and coordination, needs-led care, equity, and respect for human rights.

To deliver a high standard of mental health treatment and care, it is necessary to adopt an integrated system of service delivery that comprehensively addresses the full range of psychosocial needs of people with mental and substance use disorders (WHO, 2003).

Accessibility

Essential mental health care, including both outpatient and inpatient care, should be available locally so that people do not have to travel long distances. Accessibility also implies that services should be affordable and acceptable. Barriers to access include stigma and discrimination; low awareness of available services; a lack of well-organized primary mental health care; inadequate links between services; inadequate mental health training of primary health-care staff; and poor identification of cases in the community. Sometimes legislative barriers prevent development of effective services, such as substitution therapy programs for people with opioid dependence.

Comprehensiveness

Persons with mental and substance use disorders need and can benefit from a range of different coordinated services incorporating the use of case management, multidisciplinary teams, crisis intervention, assertive outreach, patient advocacy, and practical support as well as a range of treatment options. In addition to dealing with acute/chronic ‘health’ needs of persons, services need to address longer-term community integration needs, such as social services, housing, education, and employment. Collaboration with other sectors is essential in this regard.

Continuity And Coordination Of Care

Health systems in most countries, and especially those in developing countries, are designed to provide health care on the basis of the throughput model. This emphasizes the importance of vigorous treatment of acute episodes in the expectation that most patients will make a reasonably complete recovery without a need for ongoing care until the next acute episode. Many mental and substance use disorders, especially those with a chronic course or with a relapsing–remitting pattern, are better managed by services that adopt a continuing care model. This emphasizes the long-term nature of the disorders and the need for a continuing therapeutic input.

A continuing care approach also emphasizes the need to address the totality of patients’ needs, including their social, occupational, and psychological needs. Such approaches therefore require the coordination of patients’ medical and social care needs in the community and collaboration between different care agencies.

Needs-Led Care

To be effective, it is essential that mental health services be designed on a needs-led basis rather than on a service-led basis. This means adapting services to users’ needs, and not the other way round. Too often, services are developed and run primarily from a managerial perspective and users have to adjust to the peculiar structures of the services they need to access.

Effectiveness

Service development should be guided by evidence of the effectiveness of particular interventions and models of service provision. For example, there is a growing evidence base of effective interventions for many mental disorders, among them depression, schizophrenia, and alcohol and opioid dependence. In addition, there is growing evidence of the effectiveness of treatment and care based on the community and the general hospital.

Equity

People’s access to services of good quality should be based on need. Equity means that all segments of the population are able to access services and that possible inequities are taken into account. For most policy makers, the improvement of equity involves working toward greater equality in outcomes or status among individuals, regardless of the income group to which they belong or the region in which they reside.

Respect For Human Rights

International human rights norms and standards should be respected when providing services for people with mental disorders. People with mental and substance use disorders have the same civil, economic, political, social, and cultural rights as everyone else in the community and these rights should be upheld.

Variables Influencing Service Organization And Provision

The exact form of service organization ultimately depends on a number of wider contextual variables related to the country’s social, cultural, political, and economic contexts.

In this section we define a ‘model’ in which different, but sometimes interrelated, wider societal variables interplay to influence service organization for mental health. The model has a number of implications, one of which is that changing the mental health system toward that described in the WHO service organization pyramid will require a number of paradigm shifts. These paradigm shifts and interventions to support them are discussed in the next section.

Essentially the model defines four important groupings of variables. The first grouping refers to the level of resources of a country at large and the resources specifically devoted to the mental health system. In this context it is important to note that resources and economic development can differ considerably throughout the country, leading to vast differences in service systems, for example, between different states and between urban and rural areas.

We know that a minimal level of resources is required to provide an effective mental health system. Low-income countries, sometimes, just do not have the required resources to build effective and responsive mental health systems. Having said that, a country can be a middle or even a high-income country but still have a poorly functioning mental health system because mental health is not considered a priority for investment. Furthermore, although low economic development is a barrier to a well-functioning mental health system, some poor countries or poor areas within countries have been able to develop some innovative services. Often these make use of ‘freely’ available resources in the community as opposed to ‘more costly’ services available in the formal health system.

What is also interesting is that the more resources a country has to invest in their mental health system the more influential other variables, such as the prevailing paradigm for mental health, become in shaping that system.

Essentially, the prevailing paradigm for mental health, the second grouping of variables in this model, will greatly influence the formation of mental health service providers and clinical practice in countries. To date, there have been two distinct approaches: the biomedical approach and the psychosocial approach. The biomedical approach has been the most predominant, and continues to influence service delivery structures in most parts of the world. Its limitations are that it focuses exclusively on the physical aspects of mental disorders and not enough on psychosocial dimensions. Its influences are seen in the mental health system in terms of an over-reliance on hospital care at secondary and tertiary levels.

The psychosocial approach, in contrast, recognizes that successful treatment requires attention to biologically based treatments within the context of a broader approach to ensure that people with mental disorders are integrated into the community and leading as normal lives as possible. Where a psychosocial orientation or model operates in countries, the mental health system tends to be better geared toward the lower end of the WHO pyramid, that is, community mental health services, primary health care, and informal community services.

The third grouping refers to the value system of countries, for example, the relative importance given to individual rights and collective norms and the degree to which value systems are directed toward human rights, equality, equity, and so on.

Countries in which social control is an important feature and in which individual needs are seen as insignificant in comparison are more likely to provide a mental health system reliant purely on institutional care. In these scenarios, services as well as clinical practice are based more on ideology than evidence. Here the problem is not necessarily that there is an absence of care – in fact, in some of these countries mental health-care facilities and providers can be numerous – but that the care provided is limited to institutions emphasizing control and containment rather than rehabilitation. This is the type of care that WHO actively discourages.

Countries in which value systems emphasize human rights as well as equality and equity tend to provide mental health systems that are more (1) protective of individuals and their rights, (2) responsive to individual needs, and (3) likely to have structures in place to offer some degree of protection against violations and discrimination.

The fourth grouping of variables refers to the environment, for example, the degree to which both the political and economic environments provide long-term stability or instability . Countries undergoing rapid change, economic and political crisis, and civil war are likely to experience ongoing disruptions to any existing mental health system, and in serious conflict situations a total destruction of the existing system of care, at the very time when mental health needs are likely to be greatest. The end result of these influences is chaos, lack of coordination, and unregulated care, paralleled by greater emphasis on informal community services, a greater reliance on the private sector, NGOs, and aid programs. On a more positive note, in the rebuilding of systems following crises, the classic inhibiting factors for change, such as historical patterns of funding, no longer prevail, and so open up new opportunities to leave behind the negative and inefficient aspects of old systems in order to move toward more efficient mental health system models.

Changing The Paradigm – Important Roles Of Training, Policy, And Legislation

The knowledge base for putting in place a comprehensive mental health system is now available. Systems limited to a few large mental asylums in the main urban areas, disconnecting hospitalized people with mental disorders from their family and community, and run by a small number of overburdened health workers, are no longer acceptable. However, whereas mental health care has undergone major changes toward community-based care in some countries during the past 50 years, the majority have not been able to achieve this.

Worldwide, there remains a widespread need in many countries to radically shift models of mental health care, not only in terms of the practical organization of services but in terms of the mental health-care paradigm itself. Radically reforming or introducing new models of training and policy and legislation can help promote the required paradigm shift.

Shift From A Biomedical To A Biopsychosocial Approach

An important shift is required to move from a biomedical model to a biopsychosocial model. The evidence indicates that mental and substance use disorders result from a complex interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors and that treatment options based solely on a biomedical approach are failing because they have not addressed the psychological and social dimensions. Health-care providers need to adopt treatment approaches that (1) actively involve the patient in his or her treatment and care plan, (2) educate the main care provider or family on how to support the patient, and (3) provide for rehabilitation support, vocational support, social support, and any other intervention that may be required to help persons reintegrate into their community.

Shift To Multidisciplinary Teams

In order to take into account the many dimensions of mental health, treatment and care should no longer be delivered by any one mental health professional alone but by a multidisciplinary team, which, depending on the country, might include psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, general practitioners, occupational therapists, and community/social workers sharing their expertise and working in collaboration, each with their own roles and responsibilities. There also needs to be collaboration between mental health teams and other non-health providers in health, welfare, employment, criminal justice, and education sectors in order to meet the range of needs that people with mental disorders might have.

Reforming Education And Training Models

Radically reforming or introducing new models of training can help promote the required paradigm shift. In many developed and developing countries, the education curriculum for health and allied health professionals contains limited content in mental health. Much of what is provided is focused on institutional models of care, the diagnosis of disorders, and administration of medication, while essentially ignoring other important mental health issues and aspects of treatment. Outdated curricula act to reinforce existing and outdated mental health paradigms.

Essential to building a qualified workforce for mental health is the incorporation of mental health into the education of a wide spectrum of health workers and professionals, with mental health concepts introduced early, reinforced and expanded throughout the curricula, and developed through experiential learning opportunities. Education and training should be informed by evidence for the mental health and service requirements of the country. In most countries this requires the reorientation of the treatment framework from custodial institutional models of mental health care to community-based treatment, emphasizing the integration of mental health into general health care and the development of community care alternatives. In addition to building knowledge and skills, for example, communication and interpersonal skills training also needs to promote fundamental changes in the attitudes and beliefs of those being trained and the promotion of a human rights approach to treatment and care.

Changes To Policy And Legislative Framework

The necessary reform of services and the required paradigm shift in the attitudes, beliefs, and values of policy makers and planners can be promoted by the introduction of modern national policies and legislation in line with best practice and international human rights standards. The mental health policy of a government is the official guideline for a number of interrelated strategic directions for improving the mental health of a population, including an important focus on service delivery. A policy provides the overall direction for mental health in a country by defining the vision for the future, and the values and principles on which the vision is based, and by establishing objectives and a model for action (WHO, 2005a). A mental health plan is the operational arm of the policy and details the strategies and activities that will be implemented to achieve the objectives of the policy.

Both strategies and activities are complementary and useful tools to (1) promote development of mental health services or their reform, such as the integration of mental health into primary health care, development of community mental health services, and deinstitutionalization; (2) promote access to services in urban, rural, and poor areas and to underserved populations in a way that is affordable; and (3) improve the overall functioning of services – by, for example, committing to put in place a well-equipped workforce, good-quality treatment practices, and mental health and substance abuse information systems.

Mental health policies and plans should promote effective preventive and treatment interventions for substance use disorders within the health system; however, in addition, public health policies aimed at controlling alcohol and other substances are also required.

Mental health legislation is also a very powerful tool in that it can be used to legally reinforce these policy objectives. In addition, because it is legally enforceable and penalties can be applied it can be an effective mechanism to reduce human rights violations and discrimination, promote human rights in services and the community, and encourage autonomy and liberty of people with mental disorders (WHO, 2005b).

Despite the important role that policy and plans can have, we know that 38% of countries do not have a mental health policy, and even more countries have policies that are not implemented or that do not reflect best practice. In addition, 22% of countries do not have any mental health legislation, 57% have legislation that is more than 10 years old, and 15% have legislation dating to the pre- 1960s, before most of the currently used treatment methods became available (WHO, 2005c).

The combined effects of outdated policy and legislation are to preserve outdated thinking about people with mental disorders as incapable and ‘crazy,’ unable to make decisions for themselves, or as ‘criminals’ when related to people with drug dependence. It reinforces the use of outmoded treatment methods and institutional services and actively denies people their human rights. Modernizing policy and legislation is therefore of utmost importance to establish and enforce the basic requirements for service development, quality of care, and respect of human rights, and can as a consequence lead to changes in fundamental attitudes and beliefs and the required paradigm shift.

Bibliography:

- CDC (2001) HIV Prevention Strategic Plan Through 2005. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- Funk M, Saraceno B, Drew N, Lund C, and Grigg M (2004) Mental health policy and plans: Promoting an optimal mix of services in developing countries. International Journal of Mental Health 33(2): 4–16.

- Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, and Saraceno B (2004) The treatment gap in mental health care. Bulletin of World Health Organization 82(11): 858–866.

- Patel V (2001) Poverty, inequality and mental health in developing countries. In: Leon D and Walt G (eds.) Poverty, Inequality and Health, pp. 247–262. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Patel V, Araya R, De Lima M, Ludermir A, and Todd C (1999) Women, poverty and common mental disorders in four restructuring societies. Social Science and Medicine 49(11): 1461–1471.

- Saraceno B and Barbui C (1997) Poverty and mental illness. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42(3): 285–290.

- Saraceno B, Tarsitani L, and Fleischmann A (2003) Public health implications of depression. (WHO unpublished report).

- UNAIDS (2006) Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. A UNAIDS 10th anniversary special edition. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

- Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Grenn CA, Orleans T, and Klein J (2004) Behavioural counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: A summary of the evidence for the U.S. preventive services task force. Annals of Internal Medicine 140: 557–568.

- WHO (2001) Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. World Health Report 2001. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- WHO (2003) Organization of Services for Mental Health. Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- WHO (2004) Changing History. World Health Report 2004. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- WHO (2005a) Mental Health Policy, Plans and Programmes (updated version). Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- WHO (2005b) Stop Exclusion, Dare to Care: WHO Resource Book on Mental Health, Human Rights and Legislation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- WHO (2005c) WHO Mental Health Atlas 2005. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Cohen A (2001) The Effectiveness of Mental Health Services in Primary Care: The View from the Developing World. World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: Nations for Mental Health.

- WHO (1990) The Introduction of a Mental Health Component into Primary Health Care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- WHO (2002) Mental Health Global Action Programme (mhGAP): Close the Gap, Dare to Care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- WHO (2003) Investing in Mental Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- WHO (2003) Planning and Budgeting to Deliver Services for Mental Health. Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- WHO (2004) Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- WHO (2005) Human Resources and Training in Mental Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package.

- WHO (2007) Research and Evaluation. Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.