View sample mental health research paper on mental health promotion. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Introduction

Mental health promotion is an area of study and practice integral to the new public health and health promotion. The recognition of mental health within public health is nonetheless a recent development in many parts of the world. Mental health theory and practice have a long history of separation from physical health theory and practice. The change to a more integrated approach relates to greater public awareness of mental health and evidence of its importance to overall health and social and economic development.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Like health promotion, mental health promotion involves actions that (1) support people to adopt and maintain healthy ways of life and (2) create living conditions and environments that allow or foster health. Actions such as advocacy, policy and project development, legislative and regulatory reform, communications, and research and evaluation are relevant in countries at all stages of economic development. Mental health promotion relates to the whole population of a locality or country, often through vulnerable subgroups and particular settings. It focuses on maintenance and growth of positive mental health. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion provides a foundation for health promotion strategies that can be applied usefully to the promotion of mental health (see Lahtinen et al., 2005). It considers the individual, social, and environmental factors that influence health. It places emphasis on the control of health by people in their everyday settings in the context of healthy policy and supportive environments. The Charter’s five strategies are building healthy public policies, creating supportive environments, strengthening community action, developing personal skills, and reorienting health services.

Mental health promotion refers to improving the mental health of everybody in the community, including those with no experience of mental illness as well as those who live with illness and disability. Activities designed to promote other aspects of health, to reduce risk behaviors such as tobacco, alcohol, and drug misuse and unsafe sex, or to alleviate social and economic problems such as crime and intimate partner violence, will often promote mental health. Suicide prevention programs in countries or districts will also typically include interventions that promote mental health. Conversely, the promotion of mental health will usually have additional effects on health, productivity, and on social and economic conditions. The evaluation of outcomes can be designed to take these wider changes into account, although such an integrated view has been rare in the past.

Awareness of the importance of mental health has grown through advocacy for prevention and treatment of mental illnesses. Reports on the global burden of disease, the release of the World Health Organization’s World Health Report in 2001, ‘Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope,’ and the release of national reports on mental health since 1990 have resulted in a significant increase in awareness and action to improve the outcomes for people affected by mental illnesses or at risk of becoming ill. Even so, this attention in itself results in a restricted view of the public health approach to improving mental health. As with all other components of health, illness claims the attention of the community and policy makers. Indeed the term mental health is commonly understood as referring to mental illnesses and their prevention and treatment. The stigma attached to people living with mental illness encourages this vague use of terms and concepts in a way that is similar to but generally more pronounced than for illnesses of other types. As noted by Norman Sartorius in 1998 and in several of his other publications, this creates confusion about the meaning and value of mental health, and lowers the chance of its promotion becoming a high priority for public policy or action. Mental health is a positive set of attributes, in a person or community, which can be enhanced or compromised by environmental and social conditions.

Mental Health Promotion Across Cultures

Mental health has been described in an extensive literature in terms of a positive emotion (affect) such as feelings of happiness, a personality trait that includes the psychological resources of self-esteem and mastery, and as resilience, or the capacity to cope with adversity. Each of these models contributes to understanding what is meant by mental health. Research has aided the understanding, although much of the accessible evidence is recorded in the English language and generated in high-income countries. Progress in generating the evidence for mental health promotion depends on defining, measuring, and recording mental health in all parts of the world (see Kovess-Masfety et al., in Herrman et al., 2005).

Mental health is defined by WHO as ‘‘a state of wellbeing in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to contribute to his or her community’’ (as quoted in Herrman et al., 2005: 2). The term positive mental health is sometimes used to emphasize the value of mental health as a personal and community resource. This core concept of mental health is consistent with its wide and varied interpretation across cultures.

Positive mental health contributes to personal well-being, quality of life and effective functioning, and also contributes to society’s effective functioning and the economy. It describes a personal characteristic as well as a community characteristic. Geoffrey Rose (1992) used the mental health attributes of populations to exemplify his restatement of the ancient view that healthiness is a characteristic of a whole population and not simply of its individual members. He went on to note that just as the mildest subclinical degree of depression is associated with impaired functioning of individuals, so surely the average mood of a population must influence its collective or societal functioning. Yet the measurement of population mental health and the study of its determinants are still relatively neglected.

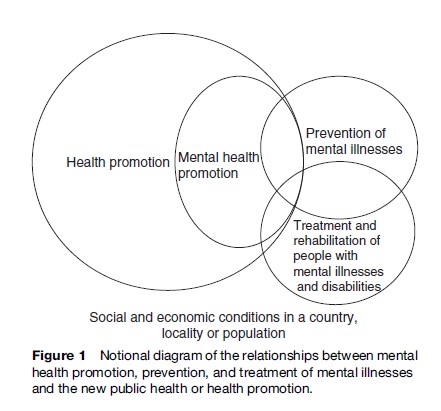

Concepts fundamental to public health, as distilled by key thinkers such as Marmot, Wilkinson, Syme, and Rose, are also fundamental to the improvement of mental health. For example, health and illness are determined by multiple factors, health and illness exist on a continuum, and personal and environmental influences on health and disease may be studied and changed and the effects evaluated. Yet these ideas are foreign to mental health for many professionals and nonprofessionals whose views are shaped by the image of asylum care for people living with apparently incurable mental illnesses. Furthermore, the promotion of mental health is sometimes seen as far removed from the problems of the real world and even as diverting resources from the treatment and rehabilitation of people affected by mental illness. As a result, the opportunities for improving mental health in a community are not fully realized. Activities that can improve mental health include the promotion of health, the prevention of illness and disability, and the treatment and rehabilitation of those affected. As in public health overall, these are different from one another, even though the actions and outcomes overlap. They are all required and are complementary to one another (Sartorius, 1998) (Figure 1).

Although the attributes defining mental health may be universal, their expression differs individually, culturally, and in relation to different contexts. An understanding of a particular community’s concepts of mental health is a prerequisite to engaging in mental health promotion (see Sturgeon and Orley, in Herrman et al., 2005). Sensitivity to the factors valued by different cultures will increase the relevance and success of potential interventions. Understanding the effects of discrimination on the lives of women in patriarchal societies or people living with HIV/ AIDS, for instance, will make a major contribution to developing relevant intervention programs. It is equally important to be aware that a culture-specific approach to understanding and improving mental health may be unhelpful if it ignores the variations within most cultures today and fails to consider individual differences. The beliefs and actions of people and groups need to be understood in their political, economic, and social contexts.

Determinants Of Mental Health

Mental health and mental illnesses are determined by interacting social, psychological, and biological factors. This is similar to the mechanism of multiple interactions understood to determine health and illness in general. Ideas about the social determinants of mental health and mental illness have evolved to reach the current understanding that gene expression can be influenced by external agents and may be shaped by social experience (see Anthony, in Herrman et al., 2005). Studies with animal models are demonstrating the mechanisms by which social experience influences the developing brain. For instance, the closeness of maternal care in laboratory mice has molecular consequences that modify the brain. Other studies are illustrating, conversely, how the brain can process social information, for example how unique molecules influence memory of social events (see Insel, in Herrman et al., 2005). A life-course approach helps in understanding social variations in health and mental health.

Research designs need to take into account these systemic interactions rather than rely only on risk factor epidemiology, by which is meant a selectively narrow focus on individual-level characteristics and behaviors. Eminent critics such as Claus Bahne Bahnson in the 1970s had earlier advocated for more research using designs that avoid old controversies about the relative significance of biological or sociological or other factors, but instead consider a larger matrix integrating the several levels or types of determinants (see Anthony, in Herrman et al., 2005).

Social Disadvantage: Poverty, Gender Disadvantage, And Indigenous Populations

In the developed and developing world, poor mental health and common mental disorders are associated with indicators of poverty, including low levels of education. The association may be explained by such factors as the experience of insecurity and hopelessness, rapid social change, and the risks of violence and physical ill health (Patel and Kleinman, 2003). Most evidence of this association relates to the prevalence of mental disorders. When mental health is understood in positive terms, the need becomes apparent for studies using positive as well as negative indicators of mental health, as well as documenting the process of health-promoting interventions.

Mental, social, and behavioral health problems can interact to intensify each other’s effects on behavior and health. The authors of the influential volume World Mental Health (Desjarlais et al., 1995) define this idea clearly. They marshal the evidence to state that substance abuse, violence, and abuses of women and children on the one hand, and health problems such as heart disease, depression, and anxiety on the other, are more prevalent and more difficult to cope with in conditions of high unemployment, low income, limited education, stressful work conditions, gender discrimination, unhealthy lifestyle, and human rights violations.

Human Rights

Respect for and protection of civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights is fundamental to mental health promotion in a community. Good mental health does not coexist with abuse of fundamental human rights. The Bill of Rights and other United Nations (UN) human rights instruments reflect a set of universally accepted values and principles of equality and freedom from discrimination, and the right of all people to participate in decision-making processes. The related legal obligations on governments can assist vulnerable and marginalized groups to gain influence over matters that affect their health. These UN instruments also serve to guide countries in the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of mental health policies, laws, and programs. They provide additional protection to vulnerable groups, including women and children in many settings, who are marginalized and discriminated against and at high risk for poor mental health and mental disorders. As human rights have civil, cultural, economic, political, and social dimensions, they provide a mechanism to consider mental health across the wide range of mental health determinants. They also underscore the need for action and involvement of a wide range of sectors in mental health promotion (see Drew et al., in Herrman et al., 2005).

Case Study: Mental Health And Psychosocial Support In Emergency Settings: The Inter-Agency Standing Committee Guidelines

The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) is formed by the heads of a broad range of UN and non-UN humanitarian agencies. It is the primary mechanism for interagency decisions in response to complex emergencies and natural disasters. In 2005 in the aftermath of the Asian tsunami, an IASC Task Force on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) in Emergency Settings was established to develop intersectoral guidelines. The guidelines are a foundational reference and guide for policy leaders, agencies, and practitioners worldwide. The Guidelines emphasize the need for protection and human rights standards, including the application of a human rights framework through MHPSS, and the need to identify, monitor, prevent, and respond to protection threats through social and legal protection.

Human rights violations are pervasive in most emergencies. Many of the defining features of emergencies – displacement, breakdown in family and social structures, lack of humanitarian access, erosion of traditional value systems, a culture of violence, weak governance, absence of accountability and a lack of access to health services – entail violations of human rights. In emergency situations, an intimate relationship exists between the promotion of mental health and psychosocial well-being and the protection and promotion of human rights:

- Advocating for the use of human rights standards such as the rights to health, education or freedom from discrimination contributes to the creation of a protective environment and supports social protection and legal protection. Using international human rights standards promotes accountability and the introduction of measures to end discrimination, ill treatment, or violence. Taking steps to promote and protect human rights will reduce the risks to those affected by the emergency.

- At the same time, humanitarian assistance helps people to realize numerous rights and can reduce human rights violations. Enabling at-risk groups, for example, to access housing or water and sanitation increases their chances of being included in food distributions, improves their health, and reduces their risks of discrimination and abuse. Providing psychosocial support, including life skills and livelihoods support, to women and girls may reduce their risk of having to adopt survival strategies such as prostitution that expose them to additional risks of human rights violations.

The IASC guidelines are designed for use by all humanitarian actors, including community-based organizations, government authorities, UN organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and donors operating in emergency settings at local, national, and international levels. Implementation requires extensive collaboration. The active participation at every stage of communities and local authorities is essential for successful, coordinated action, the enhancement of local capacities, and sustainability. Action sheets in the guidelines outline social supports relevant to the core humanitarian domains, such as disaster management, human rights, protection, general health, education, water and sanitation, food security and nutrition, shelter, camp management, community development and mass communication. Mental health professionals seldom work in these domains, but are encouraged to use this document to advocate with communities and colleagues from other disciplines to ensure that appropriate action is taken to address the social risk factors that affect mental health and psychosocial well-being.

Social Capital

Lomas (1998) notes that the way we organize society, the extent to which we encourage social interaction, and the degree to which we trust and associate with each other are probably the most important determinants of health. Putnam used the term social capital in 1995 to refer to features of social organization such as those that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit (Putnam, 1995). While Putnam and other scholars note the potential ill effects as well as benefits of social cohesion, research in recent years has demonstrated links between social capital and economic and community development. Higher social capital may protect individuals from social isolation, lower crime levels, improve schooling and education, enhance community life, and improve work outcomes. The relationships between social capital, health, and mental health, and the potential of mental health promotion to enhance social capital are now subject to active investigation (Sartorius, 2003), although related themes have a long history of study. In 1897, Durkheim proposed that weak social controls and the disruption of local community organization were factors producing increased rates of suicide (Durkheim, 1897). In 1942, Shaw and McKay linked crime to similar factors (Shaw and McKay, 1942). The study of the links between levels of social cohesion and antisocial and suicidal behavior continues, as reported by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2001 (OECD, 2001). Much work remains to be done in accounting for the mechanisms underlying the health–community link and the interrelations between social capital and mental health.

Social capital is a population attribute, not an individual status or perception, and the concept has helped to redirect research on the social determinants of health and mental health. Population health measures are usually considered as the aggregate of the individual characteristics in the population. Anthony (in Herrman et al., 2005) illuminates how the perspective of networks of individuals interacting with environments, as offered by the concept of social capital, has the potential to explain a series of collective outcomes additional to those explained by research based on individual health outcomes.

Physical Health

Physical health and mental health are closely associated through various mechanisms (see Jane-Llopis and Mittelmark, 2005). Physical ill health has adverse effects on mental health, just as poor mental health contributes to poor physical health. For example, malnourishment in infants can increase the risks of cognitive and motor deficits, and heart disease and cancer can increase the risk of depression. Depression is an acknowledged risk factor for heart disease, and the mechanisms are now being studied. Poor social support, or a perception of this, and certain types of adverse working conditions are detrimental to both physical health (e.g., cardiovascular morbidity) and mental health (e.g., depression). People living with HIV/AIDS and their families frequently experience stigma and discrimination as well as depression and other mental illnesses. Persistent pain is linked with depression, anxiety, and disability.

Mental and physical health and functioning influence each other over time by various pathways (see WHO, 2001), interacting with the social and environmental influences on health. The first pathway is directly through physiological systems, such as neuroendocrine and immune functioning. The second pathway is through health behavior. The term health behavior covers a range of activities, such as eating sensibly, getting regular exercise and adequate sleep, avoiding smoking, engaging in safe sexual practices, wearing safety belts in vehicles, and adhering to medical therapies. The physiological and behavioral pathways interact with one another and with the social environment: Health behavior can affect physiology (for example, smoking and sedentary lifestyle lower immune functioning) and physiological functioning can influence health behavior (for example, tiredness contributes to accidents). In an integrated and evidence-based model of health, mental health (including emotions and thought patterns) emerges as an important determinant of overall health (WHO, 2001).

Mental Health Promotion And The Prevention And Treatment Of Illnesses

Promotion and prevention are necessarily related and overlapping activities. Promotion is concerned with the determinants of health and prevention focuses on the causes of disease. Although the starting points are different, and the range of actions and those primarily responsible for them are also different, the activities and outcomes overlap with each other. The evidence for prevention of mental disorders (see WHO, 2004; Hosman and Jane-Llopis in IUHPE, 2000 noted below) contributes to the evidence base for promoting mental health. Beyond that, evidence for the effectiveness of mental health promotion is gained through evaluation of public health actions and social policies in various sectors and in different countries and settings (Herrman et al., 2005). The actions that promote mental health will often have as an important outcome the prevention of mental disorders. The evidence is that mental health promotion is also effective in the prevention of a whole range of behavior-related diseases and risks, as described above. It can help, for instance, in the prevention of smoking or of unprotected sex and hence of AIDS or teenage pregnancy (Orley and Weisen, 1998).

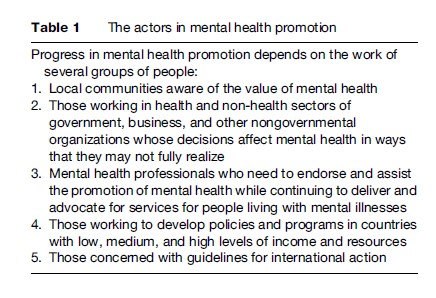

Mental health promotion actions are often social and political: Implementing interventions in schools, influencing housing and working conditions, working to reduce stigma and discrimination of various types, and developing policy initiatives to reduce violence are examples. The changes occur through decisions taken by politicians, educators, and members of nongovernmental organizations. Health practitioners are important as advocates and as aids to introducing policies that promote mental health (Table 1).

Evidence For Mental Health Promotion

Several authoritative sources summarize the evidence available for mental health promotion interventions. The landmark review from Mrazek and Haggerty in 1994 (Mrazek and Haggerty, 1994) describes a consensus on clusters of known risk and protective factors for mental health, as well as evidence that interventions can reduce identified risk factors and enhance known protective factors. The International Union for Health Promotion and Education (IUHPE) endorses the idea that mental health promotion programs work and that there are a number of evidence-based programs to inform mental health promotion practice (IUHPE, 2000; McQueen and Jones, 2007). Accumulating evidence demonstrates the feasibility of implementing effective mental health promotion programs across a range of population groups and settings (see Hosman and Jane-Llopis, 2005; Jane-Llopis et al., 2005). A major task is to promote the application of existing evidence into good practice on the ground.

The published evidence comes mainly from high-income countries. Evidence is least available from places that have the greatest need, including low-income countries and populations affected by conflicts. A challenge now is to evaluate programs and practices in these settings and populations. This may include evaluation of programs and practices based on existing evidence, or initiating research and evaluation of practices and programs established in low-resource settings. Large-scale intervention trials are needed in a range of settings. Another challenge is to monitor the mental health effects of interventions in fields other than mental health. Patel and colleagues in South Asia (Patel et al., 2004) demonstrate, for example, that maternal mental health is a critical and previously ignored factor in the association between social adversity and childhood failure to thrive in poor countries, an enormous problem in these countries. Interventions for preventing and treating postnatal depression as well as nutrition and social programs may be required, designed by members of the community according to the circumstances. Evaluation will require a variety of approaches and study designs, using qualitative and quantitative methods and indicators of process and outcome (Barry and McQueen, in Herrman et al., 2005). Violence prevention is now seen as a major element of HIV prevention and as these programs expand it will be sensible to measure their mental health outcomes.

Empowerment is the process by which groups in a community who have been traditionally disadvantaged in ways that compromise their health can overcome these barriers and can exercise all the rights that are due to them with a view to leading a full and equal life in the best of health.

Progress in mental health promotion depends on the work of several groups of people:

- Local communities aware of the value of mental health

- Those working in health and non-health sectors of government, business, and other nongovernmental organizations whose decisions affect mental health in ways that they may not fully realize

- Mental health professionals who need to endorse and assist the promotion of mental health while continuing to deliver and advocate for services for people living with mental illnesses

- Those working to develop policies and programs in countries with low, medium, and high levels of income and resources

- Those concerned with guidelines for international action

The empowerment of women, violence prevention in the community, and microcredit schemes for the alleviation of debt are examples of empowerment programs that have had a mental health impact (see Patel et al., in Herrman et al., 2005). The evidence for the effects of these programs on mental health is so far little documented. Doing so will strengthen the evidence base in order to inform practice and policy globally.

The evidence base is important to several groups for different reasons, as described by Nutbeam in relation to health promotion more broadly (see IUHPE, 2000). Researchers will have a primary concern with the quality of the evidence, its methodological rigor, and its contribution to knowledge. Policy makers are likely to be concerned with the need to justify the allocation of resources and demonstrate added value. Practitioners need to have confidence in the likely success of implementing interventions, and the people who are to benefit need to see that both the program and the process of its introduction are participatory and relevant to them. Mental health promotion considers mental health in positive rather than in negative terms. This shift requires further work in establishing positive indicators of mental health outcomes (Zubrick and Kovess-Masfety, in Herrman et al., 2005). It also requires a focus on research methods that will document the process as well as the outcomes of promoting positive mental health and identify the necessary conditions for successful implementation.

The systematic study of program implementation has been relatively neglected. A continuum of approaches is needed ranging from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to qualitative process-oriented methods such as narrative analyses, interviews, surveys, and ethnographic studies. Collections of this kind of data will advance knowledge on best practice in real settings. The development of user-friendly and accessible information systems and databases is required for both practitioners and policy makers.

These systems would respond to the urgent need to identify effective programs that are transferable and sustainable in settings such as schools and communities. Examples are the application of programs based on community development and empowerment methods, such as mutual support for mothers and for widows and school based programs for young people (Barry and McQueen, 2005). These have been shown to be highly effective, low-cost, replicable programs successfully implemented and sustained by nonprofessional community members in disadvantaged community settings. The principle of prudence recognizes that we can never know enough to act with certainty (see Mittelmark et al., in Herrman et al., 2005). Despite uncertainties and gaps in the evidence, we know enough about the links between mental health behavior and social experience to apply and evaluate locally appropriate policy and practice interventions to promote mental health (Herrman et al., 2005: XIX).

Effective programs for universal, selective, and indicated prevention of conduct disorders, depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, substance use-related disorders, and psychotic disorders are summarized in a WHO publication on prevention of mental disorders (WHO, 2004). Reducing the risk of aggressive behavior and conduct disorders, for instance, focuses on improving the social competence and pro-social behavior of children, parents, teachers, and peers. Malleable risk factors include mothers’ smoking during pregnancy, substance abuse among parents, child abuse, early substance use, deviant peer relationships, and poor and socially disorganized neighborhoods with high levels of crime. The onset of depression and its recurrence is influenced by a wide range of malleable risk and protective factors at different stages of life from infancy, including depression-specific factors such as parental depression, and generic risk factors such as child abuse and neglect, stressful life events, and bullying at school, and protective factors such as a sense of mastery, self-esteem, and social support. Effective prevention of depression therefore needs multiple actions at several levels. Prevention is possible for several forms of developmental and intellectual disabilities (for example, cretinism due to iodine deficiency) and disorders due to brain injury, although neglected in much of the world (Sartorius and Henderson, 1992). Suicide prevention programs rely on a range of social and health service interventions in any country or district, including interventions that improve treatment of depression, provide continuing care for people living with psychotic disorders, reduce harmful use of substances or control access to the means of suicide, and that promote mental health in the population in other ways. The proof that an intervention or a program is effective in preventing suicide is difficult and complicated, as suicide is a rare event (even though a leading cause of death in young people in several parts of the world) with determinants at several levels.

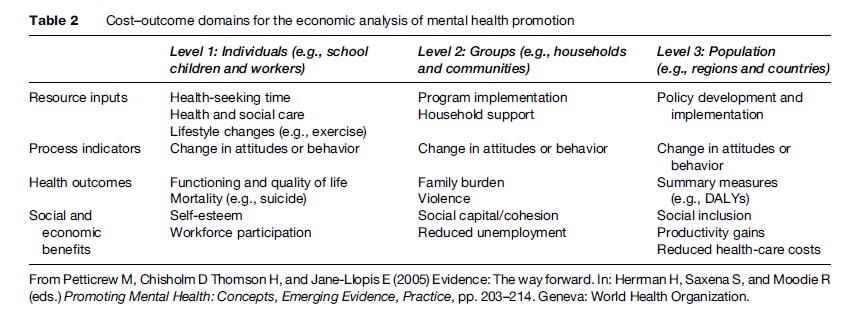

The effectiveness of exemplary mental health promotion programs and policies is summarized in recent publications (Hosman and Jane-Llopis, in Herrman et al., 2005; Jane-Llopis et al., 2005). In addition, research demonstrates that mental health can be affected by nonhealth policies and practices, for example in housing, education, and child care (see Petticrew et al., in Herrman et al., 2005) (Table 2). This work emphasizes the need to assess the effectiveness of policy and practice interventions in diverse health and non-health areas. It also demonstrates the effectiveness of a wide range of programs and interventions for enhancing the mental health of populations. These include:

- early childhood interventions;

- economic and social empowerment of women;

- social support to old-age populations;

- programs targeted at vulnerable groups such as minorities, indigenous people, migrants, and people affected by conflicts and disasters;

- mental health promotion activities in schools;

- mental health interventions at work;

- housing policies;

- violence prevention programs;

- community development programs (Herrman et al., 2005).

Improving the mental health of individuals and communities is a primary goal for some of these interventions, for example policies and programs that improve parenting skills and those that encourage schools to prevent bullying. Mental health is enhanced as a side benefit in other interventions that are mainly intended to achieve something else, for example policies and resources that ensure girls in a developing country attend school and programs to improve public housing. This distinction helps in recognizing the shared and primary responsibilities in countries and communities. Monitoring the effect on mental health of public policies relating to such things as housing and education is becoming feasible (Petticrew et al., in Herrman et al., 2005). Mental health programs in a country or locality can advocate for this, and help to ensure that findings are translated into action. Other groups will need to do the work, however, and ensure that policies and practices are shaped by the findings.

A Public Health Framework For Mental Health Promotion

Mental health promotion is expected to improve overall health, quality of life, and social functioning. Interventions designed to promote mental health, with a focus on the major determinants in vulnerable population groups, and through complex interactions including intermediate outcomes at individual, organizational, and societal levels, can result in a number of long-term benefits. In addition to improved mental health, the benefits can include lower rates of some mental illnesses, improved physical health, better educational performance, greater productivity of workers, improved relationships within families, and safer communities. The actions likely to be feasible and effective can be planned and monitored within a public health framework.

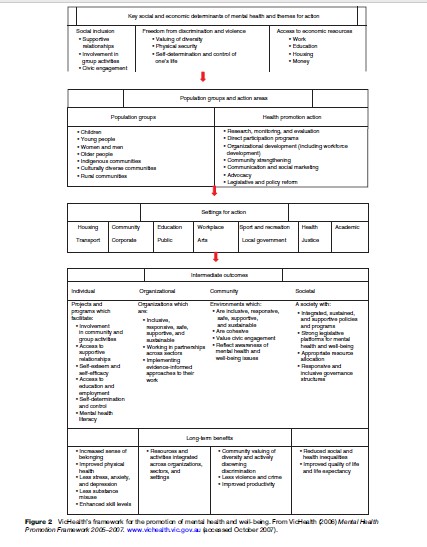

The first step in planning the activities of mental health promotion in any community or country is gathering local evidence and opinion about the main problems and potential gains, and the social and personal influences on mental health. A public health framework can help the process of assessing needs, developing partnerships, and planning actions and their evaluation. A framework includes the locally identified determinants of mental health, the population groups and areas and settings that have high priority for action, and a description of the anticipated benefits. In the case of the framework shown as an example in Figure 2 (VicHealth, 2005), the three identified determinants of mental health are social inclusion, freedom from discrimination and violence, and economic participation.

Success in promoting mental health relies on the development of partnerships between a range of agencies in the public, private, and nongovernmental sectors. Common interests need to be identified. The focus on health rather than illness can help in doing this, as well as avoid the perception of competing for resources with the health services sector, already poorly resourced in most of the world.

Research, government policy making, and practice tend to take place in systems or organizations that have little involvement with each other. Effective mental health promotion interventions in a population require integrated activity across these so-called silos: Long-term planning, investment, and evaluation are required. Long-term gains are generally not attractive to governments with immediate concerns in other areas. Effective advocacy and communication with decision makers must be developed. International collaborations can assist advocacy for mental health promotion activity in low-income as well as high-income countries and the sharing of information and expertise (Walker et al., in Herrman et al., 2005).

Policy And Practice

Mental health promotion strategies need support from the community and the government. As collective action, the success of the strategies depends on shared values as much as on the quality of scientific evidence. In some communities, the practices and ways of life maintain mental health even though mental health may not be identified as such. In other communities, people need to be convinced – as by the results of large-scale intervention trials – that making an effort to improve mental health is realistic and worthwhile (Sartorius, 1998; Herrman et al., 2005: XIX). A government’s work to develop mental health promotion strategies involves its social development policies as well as its health and mental health policies. It can use the public health framework at this level, with three main ingredients: A concept of mental health, strategies to guide mental health promotion, and a model for planning and evaluation.

Community Development And Mental Health Promotion

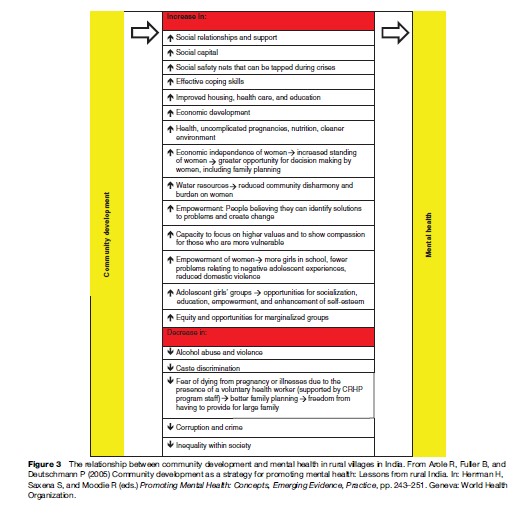

Community development aims to develop the social, economic, environmental, and cultural well-being of communities with a focus on marginalized people. Solutions to community problems are developed by local people, based on local knowledge and priorities. Work done in rural areas of India exemplifies some aspects of the relationship between community development and promotion of mental health, even where the objectives of the program may not include a specific focus on mental health. For example, a large primary health-care program in rural Indian villages directly targeting poverty, inequality, and gender discrimination has led indirectly to significant gains in mental health and well-being (Arole et al., in Herrman et al., 2005). As the interventions succeeded, the people realized the advantages of working together and they became open to approaching other issues affecting the village such as health needs and caste discrimination. An approach that is aware of the needs, interests, and responsibilities of men and women and that focuses on reducing the vulnerability and increasing the participation of women is the likely basis of the success of community development in these villages and the associated improvement in mental health (Figure 3).

Intersectoral Linkage And Community Change In Mental Health Promotion

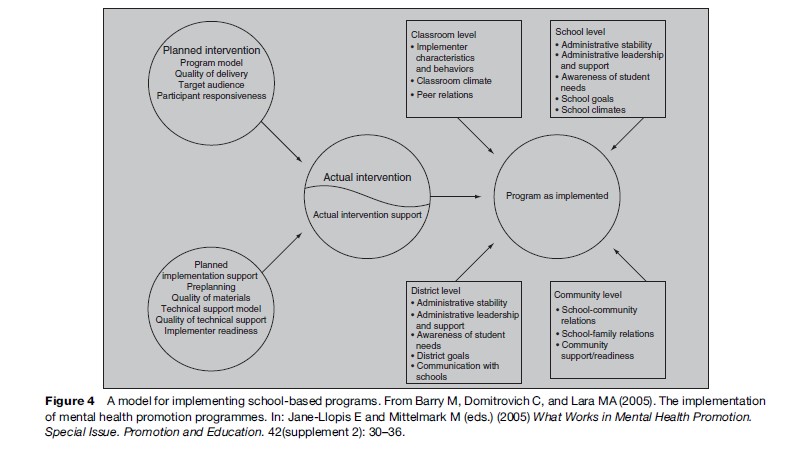

Mental health can be improved through the collective action of society. Improving mental health requires policies and programs in government and business sectors including education, labor, justice, transport, environment, housing, and welfare, as well as specific activities in the health field relating to the prevention and treatment of ill health. Policy makers are now recognizing that emphasis is best placed on adding programs that sharpen the capacity of systems, such as primary health-care systems and school systems, to be more health-enhancing. Investigating the sustainability of mental health promotion actions is therefore less about the technological aspects of programs and more about programs as change processes within organizations or communities. Programs are opportunities to recalibrate systems to higher or better levels of functioning. Evaluation also includes a more systematic analysis of the context within which programs are provided and factors within that context (such as preexisting attitudes and relationships) that could predict why some programs fade over time while others succeed and grow (see Hawe et al., in Herrman et al., 2005; Rowling and Taylor, in Herrman et al., 2005) (Figure 4).

Conclusions

Mental health is everybody’s business. Those who can do something to promote mental health and who have something to gain include individuals, families, communities, health professionals, commercial and not-for-profit organizations, and decision makers in governments at all levels. International organizations can ensure that countries at all stages of economic development are aware of the importance of mental health for human, community, and economic development and of the possibilities and evidence for intervening to improve and monitor the mental health of the population. A wide range of health and non-health decisions made by organizations and governments at local and national levels affect mental health. Mental health promotion ultimately depends on activities at the local level supported by local people and partnerships.

Bibliography:

- Anthony J (2005) Social determinants of mental health and mental disorders. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 120–131. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Arole R, Fuller B, and Duetschmann P (2005) Community development as a strategy for promoting mental health: Lessons from rural India. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 243–251. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Barry MM and McQueen DV (2005) The nature of evidence and its use in mental health promotion. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 108–120. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Barry M, Domitrovich C, and Lara MA (2005) The implementation of mental. health promotion programmes. In: Jane-Llopis E and Mittelmark M (eds.) What Works in Mental Health Promotion. Special Issue. Promotion and Education 42(supplement 2): 30–36.

- Drew N, Funk M, Pathare S, and Swartz L (2005) Mental health and human rights. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 89–108. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Durkheim E (1897, 1951) Suicide: A Study in Sociology. Spaulding JA and Simpson G (trans.). New York: The Free Press.

- Hawe P, Ghali L, and Riley T (2005) Developing sustainable programs: Theory and practice. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 252–263. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Hosman CMH and Jane-Llopis E (2005) The evidence of effective interventions for mental health promotion. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 169–189. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Insel T (2005) Promoting mental health: Lessons from brain research. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 2–13. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Jane-Llopis E, Barry M, Hosman C, and Patel V (2005) Mental health promotion works: A review. In: Jane-Llopis E and Mittelmark M (eds.) What Works in Mental Health Promotion. Special Issue. Promotion and Education 42(supplement 2): 9–25.

- Kovess-Masfety V, Murray M, and Gureje O (2005) Evolution of our understanding of positive mental health. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 35–46. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- Lahtinen E, Joubert N, Raeburn J, and Jenkins R (2005) In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 226–242. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Lomas J (1998) Social capital and health – Implications for public health and epidemiology. Social Science and Medicine 47(9): 1181–1188.

- McQueen D and Jones C (eds.) (2007) Global Perspectives on Health Promotion Effectiveness. New York: Springer.

- Mrazek P and Haggerty RJ (eds.) (1994) Reducing Risks of Mental Disorder: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- OECD (2001) The Well-Being of Nations. The Role of Human and Social Capital. Education and Skills. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Centre for Educational Research and Innovation.

- Orley J and Weisen RB (1998) Mental health promotion. The International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 1: 1–4.

- Patel V and Kleinman A (2003) Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81: 609–615.

- Patel V, Rahman A, Jacob KS, and Hughes M (2004) Effect of maternal mental health on infant growth in low income countries: New evidence from South Asia. British Medical Journal 328(7443): 820–823.

- Patel V, Swartz L, and Cohen A (2005) The evidence for mental health promotion in developing countries. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 189–202. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Petticrew M, Chisholm D, Thomson H, and Jane-Llopis E (2005) Evidence: The way forward. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 203–214. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Putnam R (1995) Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy 6(1): 65–78.

- Rowling L and Taylor A (2005) Intersectoral approaches to promoting mental health. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 264–283. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Sartorius N (2003) Social capital and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 16(supplement 2): S101–S105.

- Sartorius N and Henderson S (1992) The neglect of prevention in psychiatry. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 26: 550–553.

- Shaw C and McKay H (1942) Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Sturgeon S and Orley J (2005) Concepts of mental health across the world. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 59–70. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Walker L, Verins I, Moodie R, and Webster K (2005) Responding to the social and economic determinants of mental health: a conceptual framework for action. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 89–108. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Zubrick SR and Kovess-Masfety V (2005) Indicators of mental health. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice, pp. 148–169. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Albee GW and Gullotta TP (1997) Primary Prevention Works. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Desjarlais R, Eisenberg L, Good B, and Kleinman A (1995) World Mental Health: Problems and Priorities in Low-Income Countries. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Herrman H, Saxena S, and Moodie R (eds.) (2005) Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice. A Report from the World Health Organization Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in Collaboration with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) and The University of Melbourne. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Hosman C (2001) Evidence of effectiveness in mental health promotion. In: Lavikainen J, Lahtinen E, and Lehtinen V (eds.) Proceedings of the European Conference on Promotion of Mental Health and Social Inclusion. Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (Report 3). Helsinki, Finland: Edita.

- Institute of Medicine (2001) Health and Behavior: The Interplay of Biological, Behavioral, and Societal Influences. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- IUHPE (2000) The Evidence of Health Promotion Effectiveness: Shaping Public Health in a New Europe, 2nd edn. Brussels, Belgium: International Union for Health Promotion and Education.

- Jane-Llopis E and Mittelmark M (eds.) (2005) What Works in Mental Health Promotion. Special Issue. Promotion and Education. 42(supplement 2): 9–45.

- Jenkins R and Ustun TB (eds.) (1998) Preventing Mental Illness: Mental Health Promotion in Primary Care, pp. 141–153. Chichester, UK: John Wiley.

- Keys CL and Haidt J (eds.) (2003) Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Lahtinen E, Lehtinen V, Riikonen E, and Ahonen J (eds.) (1999) Framework for Promoting Mental Health in Europe. Helsinki, Finland: National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health (STAKES).

- Rose G (1992) The Strategy of Preventive Medicine. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Sartorius N (1998) Universal strategies for the prevention of mental illness and the promotion of mental health. In: Jenkins R and Ustun TB (eds.) Preventing Mental Illness: Mental Health Promotion in Primary Care, pp. 61–67. Chichester, UK: John Wiley.

- Tudor K (1996) Mental Health Promotion: Paradigms and Practice. London: Routledge.

- VicHealth (2006) Mental Health Promotion Framework 2005–2007. www.vichealth.vic.gov.au (accessed October 2007).

- World Health Organization (2001) Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. The World Health Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2004) Evidence for Prevention of Mental Disorders: Effective Interventionsand Policy Options. Summary Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.