Sample Eating Disorders Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Two major eating disorders have been defined and operationalized: anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN). In recent years preliminary definitions have been given for a third eating disorder: binge eating disorder (BED). Anorexic and bulimic eating disorders usually begin in adolescence and young adulthood and more than 90 percent of the cases of AN and BN are female. Eating and food intake can have very different functions: eating fulfills the biological necessity of keeping us alive, but it can also be a source of pleasure and joy. Food intake plays an important role when we relax or celebrate with other human beings (festivities). For a person who hungers unvoluntarily this can be bothersome or painful. On the other hand, an anorexic patient who has achieved reducing weight considerably to a pathological level will be proud of the result. Refusal to eat on the level of society can be used as a means of political pressure (hunger strike). Within a family system the refusal to eat of an anorexic girl can—in the lack of other possibilities of expression—be an attempt to find and define herself; it can be a sign of inner resistance and defense against the intrusion of others. The anorexic patient avoids confrontation with the increasing demands of the role of an adult person (sexuality, relationships, profession, achievement) and regresses to an earlier more infantile stage. Eating too much as well as eating too little can be damaging to mental and physical health.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Clinical Features (Diagnoses And Differential Diagnoses)

1.1 Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia nervosa is characterized by a refusal to maintain body weight at or above a minimally normal weight for age and height, an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat even though underweight, a disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced with undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation. Frequently the seriousness of current low body weight is denied or hidden. In postmenarcheal females, amenorrhoea is the fourth diagnosic criteria; its usefulness has, however, been questioned by some research groups; anenorrhoea largely is secondary to low body weight and the starvation syndrome. Laboratory tests are usually of little help for diagnosing AN. Diagnosis is made primarily on the basis of a thorough psychiatric examination in which it is a task of the examiner to find out the motives behind being underweight. According to the DSM-IV criteria of the American Psychiatric Association (1994) two subtypes of AN can be distinguished: (a) the restricting type and (b) the binge eating purging type.

AN is frequently associated with social withdrawal, irritability, insomnia, depressed mood, and diminished interest in sexuality. In part, these depressive features are secondary to starvation and disappear with weight restoration. Preoccupation with thoughts about food, collecting recipes, and hoarding food are frequently seen in AN patients. In more than a third of AN cases obsessive compulsive features unrelated to food and eating are also present. Associated with AN can also be an exaggerated need to control one’s environment, concerns about eating in public, feelings of ineffectiveness, inflexible black and white (dichotomous) thinking, an overly restrained initiative, and emotional expression. AN patients of the binge eating purging type (in comparison to restricting anorexics) more frequently have problems in impulse- control, abuse of alcohol or other drugs, lability of mood, and they are sexually more active.

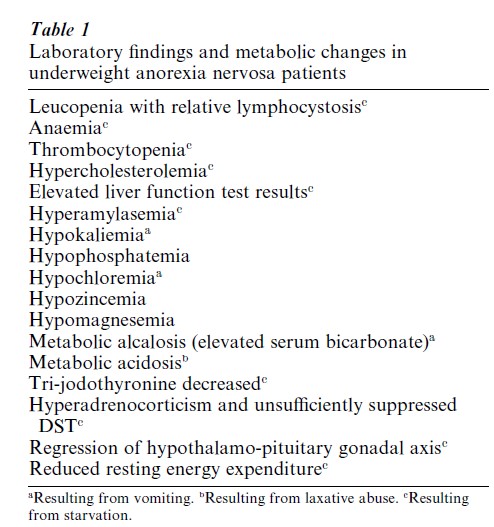

Starvation and/or inappropriate compensatory behaviors (vomiting, use of laxatives, etc.) have a variety of effects on most organ systems. Table 1 lists a number of laboratory findings usually found in starving AN patients. Except for hypokaliemia, hypochloremia, and metabolic alcalosis which are secondary to vomiting and metabolic acidosis resulting from laxative abuse, most laboratory findings are secondary to the state of starvation and the peculiar eating behaviors and eating patterns. Clinically the reduced activity of the sympathetic nervous system goes hand in hand with bradycardia, the development of fine downy body hair (lanugo), low blood pressure, constipation, cold intolerance, petechiae in the extremities, and peripheral edema during weight restoration.

1.1.1 Differential Diagnosis. Occasionally general medical conditions (gastrointestinal disease, occult malignancies, brain tumors, unclear infectious diseases) associated with weight loss are misdiagnosed as AN. When diagnosing AN it is important not to focus primarily on the emaciated state but rather on the psychological features explicated in the diagnostic criteria for AN. For the physician it is important to search for a psychological motive for reducing weight. In psychiatric disorders such as depression or schizophrenia, weight loss may occur, which, however, is secondary and not resulting from a drive for thinness as in AN.

Compulsive disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, and social phobia concur with AN not infrequently. AN of the binge eating purging type can be very similar to BN and the differentiation is (rather artificially) based on current body weight.

1.2 Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia nervosa (BN) also occurs like AN predominantly in adolescent girls or young women. Its essential features are binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain. In these patients usually self-evaluation is excessively influenced by body shape and weight. According to the DSM-IV criteria, a binge is defined on objective grounds (rather than subjective) as ‘eating in a discrete period of time an amount of food that is definitely larger than most individuals would eat under similar circumstances.’ Continuous snacking (eating small amounts of food throughout the day) which may also occur would not qualify as a typical (objectively defined) binge. Diagnosis of BN according to DSMIV criteria requires that binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors both occur on average at least twice weekly for three months.

Associated laboratory findings are very similar to those reported for binge eating purging AN. Fluid and electrolyte abnormalities (hypokaliemia, hyponatremia, hypochloremia), metabolic alcalosis with elevated serumbicarbonate resulting from vomiting or metabolic acidosis from laxative abuse, dentrocavities, enlargement of the parotid glands, and rarely but potentially fatal esophageal tears, gastric rupture, and cardiac arrhythmias.

1.2.1 Differential Diagnosis Of BN. Disturbed eating behavior can be present in certain neurological or general medical conditions such as the Kline–Levin syndrome; however, certain key features of BN such as overconcern with body shape and weight are lacking. Also, a multi-impulsive form of BN has been described in which several impulsive behaviors are observed (impulsive stealing, impulsive drinking, impulsive suicidal acts, impulsive self-damaging behavior). Prognosis for this subgroup seems to be worse than for BN in general.

1.3 Binge Eating Disorder

Binge eating disorder (BED) is defined as being very similar but not identical to nonpurging BN. Main features of BED are binge eating at least twice weekly over a period of six months, associated with marked distress. However, in BED no inappropriate compensatory behavior to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting, use of laxatives, diuretics or other medication, is present. Many but not all BED patients are overweight. Overweight BED patients have the usual risks associated with obesity (hypertension, orthopedic problems, diabetes, etc.). They do not have the risks of purging behavior observed in binge eating purging AN and BN (electrolyte imbalance, alcalosis acidosis from laxative abuse, sialadenosis from vomiting, severe dental problems from vomiting, renal failure). New research indicate that BED has many similarities with BN but that BED is quite dissimilar from AN. Very few anorexics later develop BED and very few BED patients later develop AN.

As in BN, neurological and other general medical conditions associated with bingeing and weight gain must be differentiated from BED.

1.4 Eating Disorders—Not Otherwise Specified

The eating disorders—not otherwise specified (EDNOS) category is for disorders of eating that do not meet the criteria of any specific eating disorder such as AN, BN, and BED. In DSM-IV six examples are given. Usually one criteria of a major eating disorder (AN, BN) is not met. One of several examples for EDNOS is: all of the criteria of BN are met, except that the binge eating and inappropriate compensatory mechanisms occur at a frequency of less than twice a week and for a duration of less than three months.

2. Epidemiology, Course And Prognosis

2.1 Anorexia Nervosa

A number of studies indicate that the prevalence of AN has increased over the decades of the twentieth century—especially since the 1960s. Research among females in late adolescence and early adulthood have revealed rates of 0.4–1.1 percent for presentations that meet full criteria for AN according to DSM-IV. Less than 10 percent of all treated cases with AN are male. Mean age at onset for AN is 16–18 years. Onset very rarely occurs in individuals over age 40 years. The onset of illness is frequently triggered by life events which increase uncertainty, cause anxieties, and put new demands on the individual. The mortality rate of patients with AN is only second to that of politoxicomanic drug use and dependence and it is much higher than for schizophrenia or depression. Over the long-term course of 20 years, 10–15 percent of patients with AN die from starvation, suicide, or electrolyte imbalance (which can cause cardiac or renal failure (Ratnasuriya et al. 1991). First-degree relatives of patients with AN have an increased risk for that disorder. Mood disorders have also been found to be more prevalent in the biological relatives of individuals with (binge eating purging type) AN.

2.2 Bulimia Nervosa

Among adolescent and young adult females the prevalence of BN is about 0.8–3 percent. As in AN, the disorder is usually found in pubertal girls or young adult women; less than 10 percent of the cases of BN are men. The onset of BN is usually in late adolescence and early adult life. Although patients with BN at times can be very tough to treat, the course over a time is not as malignant as it can sometimes be in AN. Frequent and excessive dieting may trigger the start of binge eating. In a high percentage of clinical samples the disturbed bulimic eating behavior persists over several years and the course can be chronic or intermittent or with remission. In the last few years several studies have reported on the sixto 10-year course of BN (Fichter and Quadflieg 1997a). The outlook for BN patients is not quite as pessimistic as for AN patients: although about a third of treated cases show a more or less chronic course; the majority at six-year follow-up no longer fulfill the criteria for a major eating disorder. This, however, does not mean that all are free of eating disorder symptoms which in some way interfere with their everyday life.

2.3 Binge Eating Disorder

The prevalence of BED is roughly the same as for BN (1.5 percent among adolescent and young adult females). Although BED is predominantly found in females, the proportion of males is higher than in AN or BN. The shortand medium-range course of BED appears to be equivalent to that of BN (Fichter et al. 1998). Research indicates that besides BED there are other eating disorders associated with overweight not fulfilling criteria for BN or BED. Psychiatrists have carried out very little research on obese patients with atypical binges (continuous snacking throughout the day) and mental problems resulting from getting obese on the basis of a general medical condition (endocrinological disturbance) or medication which increases appetite and body weight (neuroleptics, certain antidepressants, lithium, etc.).

3. Etiology And Pathogenesis

For the pathogenesis of anorectic and bulimic eating disorders the following factors must be taken into consideration: (a) sociocultural factors (mediated through family, school, and mass media), (b) biological factors (genetic, neurochemic), and (c) life events and chronic difficulties.

3.1 Sociocultural Factors

Eating disorders are fairly prevalent among young women in industrialized countries where the ideal of body thinness exerts considerable pressure especially on adolescent girls and young women. Most young women have dieted once, several times, or many times—some successful, many not. In industrialized countries food exists in abundance. Studies in Third World countries have shown that anorexic and bulimic eating disorders are seen rarely there and if they occur the patient was usually from a well-to-do family. Among persons who migrated from a Third World country to an industrialized country and who were thus exposed to ideals and pressures to be slim, anorexic and bulimic eating disorders are seen more frequently than among those who remained in the country of origin.

The ideals of body slimness (especially for women) and the ideal of body fitness (especially for men) are very prevalent in industrialized countries and exert pressures on individuals. We do not know exactly why these ideals exist and how they came about but some interesting explanations exist. From an anthropological–evolutionary perspective, it is important to note that mankind never in its history has had an abundance of food in such a large proportion of the population over such a long period of time. During the evolution of mankind, food at times was scarce and our predecessors would not have survived if they had not developed special biological adaptations to periods of hunger and starvation. When we reduce our food intake and lose body weight many adaptive physiological adaptations take place which help us save energy (bradycardia, hypotension, lowering of T3, hypercortisolism, and temporary loss of reproductive functions). Mankind, however, is biologically very ill-equipped for dealing with food abundance over very long periods of time. The abundance of food appears to be a necessary but not sufficient factor contributing to the etiopathogenesis of these eating disorders.

3.2 Biological Factors

A number of twin studies have shown relatively high concordance rates among monozygotic compared to dizygotic twins especially for AN but also for BN. Currently large studies using the techniques of molecular genetics are underway but the results are not yet available. AN and BN frequently have an onset around puberty, the time when, due to hormonal changes, the body undergoes considerable changes. Starting at puberty, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) are secreted regularly, inducing the secretion of gonadal hormones which have an impact not only on our body but also on our brain. Also, body fat is not distributed the same way in men and women. There exists a sexual dimorphism: the fat deposits of men are predominantly in the abdominal region and those of females are primarily observed on the trunk, buttocks, and the extremities.

The hypothalamus plays an important role in the regulation of eating behavior. Simplifying a highly complex regulation, one can speak of an ‘eating center’ in the lateral hypothalamus and a ‘satiety center’ in the medial hypothalamus. Electrical stimulation of the ‘eating center’ or making a lesion in the ‘satiety center’ results in excessive eating. Stimulating the ‘satiety center’ or putting a lesion into the ‘eating center’ results in loss of appetite, loss of weight, and finally death.

3.2.1 Control Of Food Intake. The following substances secreted in the human body have been shown to reduce hunger or food intake: (a) corticotropinreleasing hormone (CRH) which is secreted in the hypothalamus, (b) certain peptides secreted centrally or peripherally such as cholecystokinin (CCK), glukagon, bombesin, gastrin-releasing peptide, somatostatin, neurotensin, and leptin, and (c) the monoamine serotonin. Other substances increase food intake, such as the neuropeptide Y and the peptide YY, galanin, beta-endorphine, dynorphine, growthhormone-releasing-hormone, and the monoamine epinephrine. In animal experiments it has been shown that overeating can become a conditioned response to stress.

3.2.2 Hormonal Adaptations. Most if not all hormonal changes observed in AN and to some extent also observed in other eating disorders (BN, BED) are a sign of adaptation to a temporarily reduced food intake or low body weight. In emaciated patients with AN (as in healthy starving individuals), hypercortisolism and insufficiently suppressed cortisol response following application of dexamethasone are observed. During starvation the hypothalamo– pituitary–gonadal system is shut down so that reproduction cannot take place. The 24-hour secretory pattern of the luteinizing hormone (LH) and the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) regress to a pubertal or infantile pattern. Plasma levels of estradiol and progesterone are practically down to zero in emaciated anorexic patients, resulting in amenorrhoea. Normal-weight bulimic women show ovary dysfunctions. About 50 percent of them have unovulatory cycles and 40 percent show defects in the lutal phase (Fichter 1992). Underweight anorexic patients show increased levels of insulin and glucose following a test meal. When body fat is metabolized during starvation, free fatty acids and ketone bodies are increased in the plasma. They can serve as state markers for a negative energy balance. In emaciated patients with AN, the activity of the sympathetic nervous system is reduced, resulting in bradycardia, hypotension, and dsregulation of body temperature. These are also mechanisms for saving energy during starvation. Emaciated anorexics also appear to have lower levels of serotonin and its metabolites. Starvation in healthy subjects as well as starvation in AN subjects results in brain atrophy demonstrated in CT and MRT studies.

3.3 External Factors

Life events and chronic difficulties may over time make an individual vulnerable to later develop an eating disorder or may trigger its onset. During the time of adolescence not only bodily changes occur but also the individual is confronted with new demands. They are now expected to have more responsibilities and they are increasingly confronted with contacts and relationships with the other sex. Especially during adolescence, feeling left out or rejected by others can hurt deeply and increase vulnerabilities. Developing an eating disorder is a way of avoiding failures in everyday life because a wide range of important things in life are reduced to a small area of shape and weight concerns. In controlling her weight an anorexic girl can succeed. In some families with an anorexic patient, family relationship interactions cause problems. Research in this area, however, is difficult because what we see in clinical cases can be the reaction of a family to the illness rather than its cause (Russell et al. 1987). More solid research is needed in this area.

4. Treatment Of Eating Disorders

4.1 General Aspects

Details on the treatment of eating disorder are given in the practice guidelines of the American Psychiatric Association (2000) which can be obtained through the internet (http://mentalhealth.uca.edu/apa.scpg/eating-disorders). Antidepressants such as serotonin re-uptake inhibitors can be beneficial in the therapy of BN and BED. Their efficacy in AN has not clearly been established.

4.2 Psychological Therapies

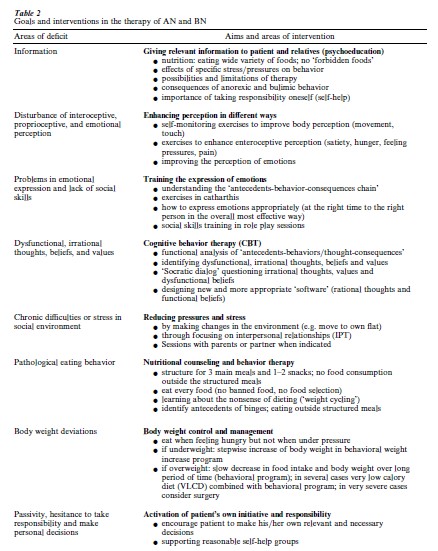

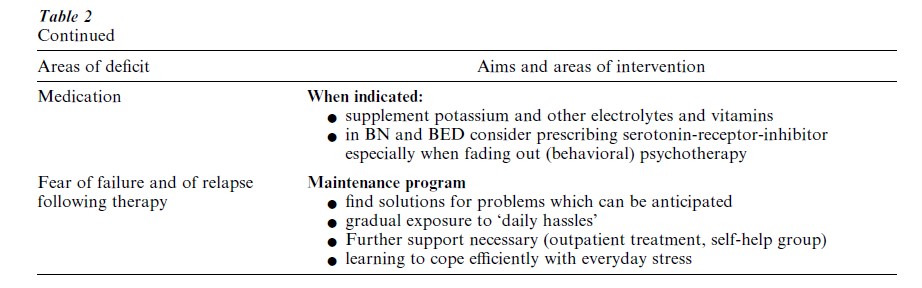

There exists a wealth of data on the efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) in BN (Agras et al. 2000). CBT has also been shown in some studies to be effective in BED. Although there are several controlled studies on the therapy of AN, research in the past two decades has focused on BN and BED and further controlled studies on the treatment of AN are needed. Table 2 shows major areas of intervention for anorexic and bulimic eating disorders. Most controlled trials on psychological therapy have focused on dealing with dysfunctional, irrational thoughts and beliefs using cognitive behavior therapy or have focused on directly modifying the eating behavior. However, it has also been shown that other forms of therapies such as nutritional management or interpersonal therapy which are completely different can be effective treatments for BN.

4.3 Specific Aspects For The Therapy Of AN

When a patient is severely emaciated, psychological therapies alone will not lead very far; motivating the patient to eat more and gain weight is then very important. Some patients gain weight when they are encouraged and supported to do so; others need structured behavioral programs with strong incentives for weight gain. In a few patients both these approaches will fail and tube feeding will at least for a certain period of time be necessary. Weight increase of about 150 grams per day is desirable. Other focuses of the treatment of AN are listed in Table 2 (enhancing perception, training of the expression of emotions, enhancing social skills, cognitive restructuring of dysfunctional thoughts and beliefs, normalizing eating behavior, dealing with anxieties, and encouragement to take on new responsibilities).

Most controlled treatment studies with BN patients use cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) with some variation of it. Some studies have shown the usefulness of behavioral management of eating behavior, interpersonal therapy, nutritional counseling, and guided self-help. Little attention has been given by researchers to assess treatment, focusing on disturbances of interoceptive, proprioceptive, and emotional perception which according to Hilde Bruch (1973) is a central feature of all eating disorders (Laumer et al. 1997). For dysfunctional behaviors such as bingeing it is of importance to identify antecedent events which trigger the dysfunctional behavior of the patient. In the next step when antecedence, behavior, and consequences are clearer, behavioral interventions such as social skill training can be employed to improve coping in future problem situations.

In addition to the other areas listed in Table 2, body weight control and management is of special importance for the treatment of patients with BED if they are overweight or obese.

Bibliography:

- Agras W S, Walsh B T, Fairburn C G, Wilson G T, Kraemer H C 2000 A multicenter comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry 57: 459–66

- American Psychiatric Association 1994 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

- American Psychiatric Association 2000 Practice Guidelines on Eating Disorders. http://mentalhealth.ucla.edu/apa.scpg/eating-disorders/page01.html-page81.html

- Brownell K D, Greenwood M R C, Stellar E, Shrager E E 1986 The effects of repeated cycles of weight-loss and regain in rats. Physiology and Behavior 38: 459–64

- Bruch H 1973 Eating Disorders: Obesity, Anorexia Nervosa, and the Person Within. Basic Books, New York

- Fichter M M 1985 Magersucht und Bulimia. Springer, Berlin

- Fichter M M 1990 Psychological therapies in bulimia nervosa. In: Fichter M M (ed.) Bulimia Nervosa. Wiley, Chichester, UK, pp. 273–91

- Fichter M M 1992 Starvation-related endocrine changes. In: Halmi K A (ed.) Psychobiology and Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa. American Psychiatric Press, Washington DC

- Fichter M M, Pirke K M, Holsboer F 1986 Weight loss causes neuroendocrine disturbances: Experimental study in healthy starving subjects. Psychiatry Research 17: 61–72

- Fichter M M, Quadflieg N 1997a Six-year course of bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders 22: 1–24

- Fichter M M, Quadflieg N 1997b Six-year course and outcome of anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders 26: 359–85

- Fichter M M, Quadflieg N, Gnutzmann A 1998 Binge eating disorder: Treatment and outcome over a six-year course. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 44: 385–405

- Garfinkel P E, Lin E, Goering P, Spegg C, Goldbloom D S, Kennedy S, Kaplan A S, Woodside B 1995 Bulimia nervosa in a Canadian community sample: prevalence and comparison of subgroups. American Journal of Psychiatry 152: 1052–8

- Harris E C, Barraclough B 1998 Excess mentality of mental disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 173: 11–53

- Laumer U, Bauer M, Fichter M, Milz H 1997 Therapeutische Effekte der Feldenkrais-Methode ‘Bewußtheit durch Bewegung’ bei Patienten mit Essstorungen. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie 47: 170–80

- Ratnasuriya H, Eisler I, Szmukler G, Russell G F M 1991 Anorexia nervosa: outcome and prognostic factors after 20 years. British Journal of Psychiatry 158: 495–502

- Russell G F M, Szmukler C 1987 Dare: An evaluation of family therapy in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry 44: 1047–56