View sample public health research paper on torture and public health. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Introduction

Historically, the practice of torture focused on the dyad of the torturer and his or her victim in the quest to obtain information. In the past few decades it has become clear that the impact of torture is far beyond the individual and includes society as a whole. The practice of torture is an attempt to instill fear in the community, not merely to oppress a single individual, and as such, the public health impact of torture is far reaching. In response to increasing recognition of torture as a public health problem, a field of research is evolving which seeks how best to help survivors. International law has also provided mechanisms to hold perpetrators accountable. However, the ultimate human rights and public health goal is to prevent torture from occurring at all.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Defining Torture

Torture has been practiced over the centuries, at times in public view and often with social and government sanction. But it was only in the wake of the atrocities of World War II that torture was publicly condemned as an abuse of human rights. Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), proclaimed that ‘‘No one shall be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.’’ The World Medical Association’s Declaration of Tokyo (1975) provided the first explicit definition of torture, declaring that it was the ‘‘deliberate, systematic or wanton infliction of physical or mental suffering by one or more persons acting alone or on the orders of any authority, to force another person to yield information, to make a confession, or for any other reason.’’ Ten years later, governments united to denounce state-sponsored torture when they ratified The Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984) which defines torture as:

any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or her or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.

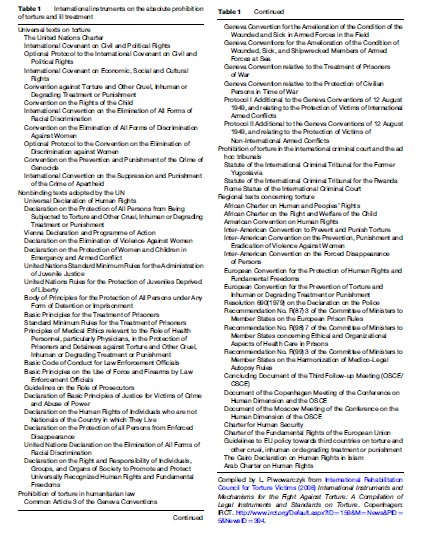

Today there are many international and regional instruments prohibiting torture and ill-treatment, which are listed in Table 1. Some of those declarations and treaties have helped develop mechanisms by which torture can be monitored and perpetrators held accountable, which is discussed further on.

Epidemiology

As the global community has turned its attention to torture, reporting of torture has increased. The Amnesty International (AI) Annual Report (2006) showed that torture and ill-treatment currently occur in 150 countries. However, torture still goes underreported. Survivors often choose not to disclose their experiences, because of fear of putting themselves and their families in further danger, impairment of memory resulting from torture, cultural sanctions, or simply as a coping strategy (Mollica and Caspi-Yavin, 1991). Therefore, it is difficult to determine the true prevalence of torture.

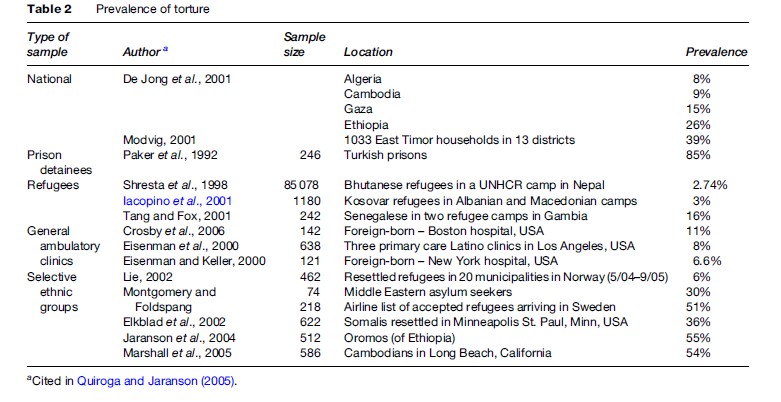

Complex humanitarian disasters, characterized by massive population dislocation, are often accompanied by an erosion of international humanitarian law and a breakdown of security which put individuals at greater risk of being subject to torture. Torture is frequently an element of war, conflict, ethnic and religious persecution, and ethnic cleansing, although it can also be an isolated event. Today, there are 9.2 million refugees and approximately 10 million people of concern (asylum seekers, returned refugees, internally displaced persons, stateless persons, and others) who are at high risk for human rights abuses (UN High Commission for Refugees, 2006). Torture can be found in 5–30% of the world’s refugees, and in even higher percentages in certain ethnic groups (Baker, 1992; Jaranson et al., 2004). Efforts have been made in a variety of settings to document the prevalence and incidence of torture in community and clinic samples, and across specific cultural groups and ethnicities; the results are summarized in Table 2.

Torture As A Public Health Problem

Impact

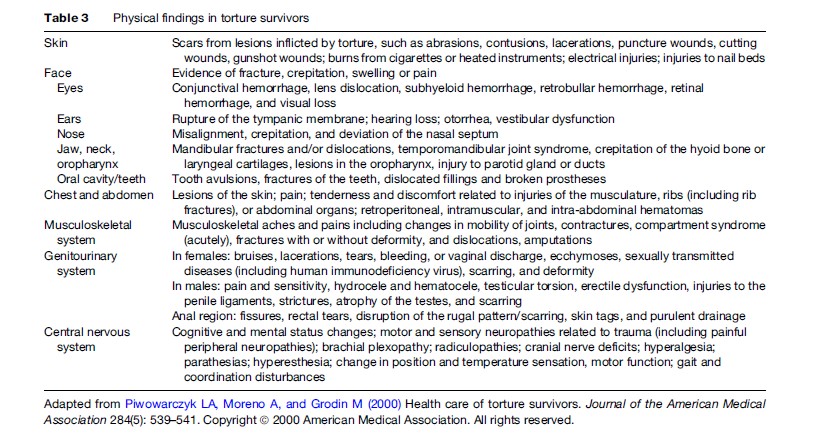

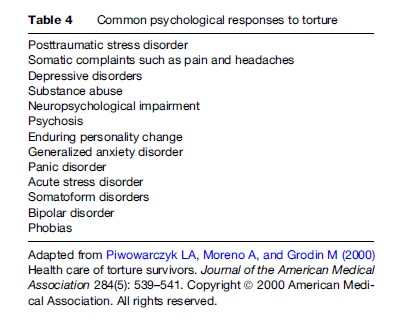

Torture is highly destructive toward individuals and can have long-term physical and psychological effects on survivors, which are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4. There is international discourse about the potential psychological sequelae in torture survivors, and at one time, questions were raised as to the presence of a torture syndrome. This idea was replaced by Western phenomenology using diagnostic criteria such as ‘posttraumatic stress disorder’ and ‘depression.’ Globally questions have been raised about the possibility of different cultural expressions of traumatic stress, which require more cross-cultural research to be resolved.

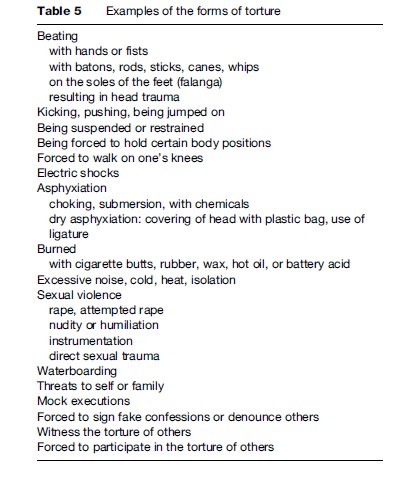

Torture can take many different forms, some of which are quite common and others that are specific to certain geographic regions. Examples of different forms of torture are listed in Table 5. As a response to the increase in human rights monitoring over the past few decades, torture methods are now often devised so that they leave no physical signs or evidence of torture after the fact (Forrest, 1996).

Although torture victims are sometimes killed, the true aim of torture is not murder, but to send a message of fear to the community through the returning victim. The traumatic effects of torture can be transmitted intergeneration ally to the family, thus spreading the impact beyond the individual (Danieli, 1998). Torture also has impacts on the broader community by sowing widespread mistrust of the government and social structures. When military and police officials commit acts of torture, they undermine the relationship between peoples and their government. Sadly, health professionals also sometimes participate in torture; physicians and psychiatrists can be employed to monitor torture, approve its continuation, and write fraudulent documentation, including death certificates and medical records of injuries sustained by torture victims (Miles, 2006). These acts of complicity by medical professionals validate the culture of torture. The impacts of torture on a community which must live in constant fear of reprisals affect the ability of citizens to challenge the status quo or speak in favor of human rights.

Prevention

The end goal of human rights advocates and health professionals is the complete eradication of torture. However, there are many levels to the prevention of torture. Primary prevention focuses on high-risk groups which may be recruited for involvement in torture, including medical professionals and law enforcement officials, and uses training to help these individuals prevent acts of torture. Secondary prevention can include human rights monitoring in areas of social unrest or political instability. Tertiary prevention encompasses the institution of legal frameworks which allow survivors of torture to seek justice and restitution.

Public involvement in the prevention of torture is helpful in bringing pressure on governments and also important because civilians are frequently targeted for torture. When a spotlight is placed on any known acts of torture, perpetrators are more likely to be held accountable for their actions, and society engages in broad discussions about the inalienability of certain human rights. Increased public awareness of the prevalence of torture and its impacts on society makes it more difficult for perpetrators to attempt to justify their actions as necessary for the defense or stability of society.

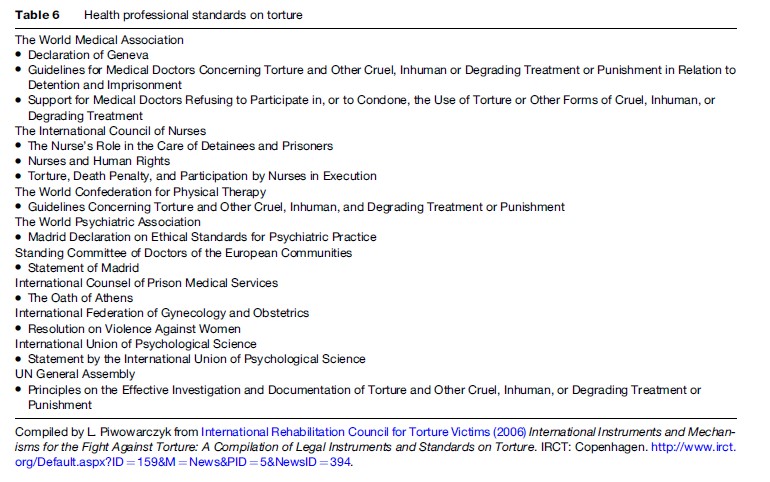

Health professionals, especially, can engage in the prevention of torture on many levels. Not only can physicians provide direct care to survivors and provide expert testimony for individuals seeking asylum, but also public health professionals in general can act on the front lines of torture prevention through identification of possible victims and perpetrators, research on torture, and education. It is critical for professional organizations around the world to speak out against torture, to support members working on behalf of survivors, and to hold accountable any health professionals involved in or complicit with acts of torture. There are specialized organizations for health and legal professionals, including Amnesty International, Physicians for Human Rights, Global Lawyers and Physicians, and Human Rights First. However, to reach a broader base of support it is important that broader national or international professional organizations, such as the American Medical Association and the World Medical Association, take on torture as a health problem. Clear ethical statements and guidelines by professional organizations about involvement in torture, such as those listed in Table 6, are important aids to prevention, as is offering continuing education to members. Advocacy for not just an end to torture itself but also for strong international humanitarian law and legal frameworks of accountability is critical for solving the problem.

Legal Frameworks For Reporting And Responding To Torture

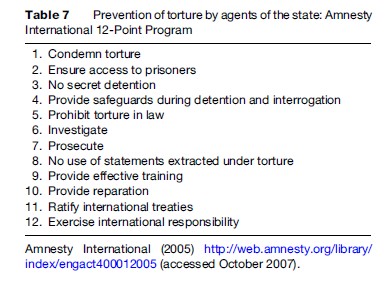

The first campaign against torture launched by Amnesty International (AI) in December 1972 was meant to educate the public and engage governments in ending torture. In 1984, AI’s second campaign developed a 12-point program for the prevention of torture, summarized in Table 7 (Amnesty International, 1983) This campaign added weight to the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which was adopted by the United Nations (UN) in that same year, although it didn’t come into force until 1987. This convention requires state parties to outlaw and prevent torture within their borders, and speaks to the complete indefensibility of torture as well as the need for accountability. It also established a monitoring body, the Committee against Torture, which in certain jurisdictions conducts investigations, hears complaints against torture, and receives state reports on states’ compliance with the Convention.

Since the Convention against Torture went into effect, several other monitoring bodies have been created. The Special Rapporteur on Torture reports to the UN High Commission on Human Rights, which investigates complaints. In addition, the Optional Protocol to the UN Convention against Torture (United Nations General Assembly, 2002) put in place a subcommittee to the UN Committee against Torture, international visiting bodies, and a national visiting body which go to detention centers to monitor for torture. The work of the Committee for the Prevention of Torture has shown that monitoring can (1) provide opportunities to make recommendations about conditions and procedures; (2) facilitate ongoing communication between authorities and detention personnel; (3) provide support to detainees; and (4) encourage detention personnel to improve conditions (United Nations, 2002).

The European Convention for the Prevention of Torture (1989) established a further commitment to monitor special populations, including persons institutionalized in psychiatric hospitals and prisons. The terms of this convention allow monitors unlimited access to any persons ‘‘deprived of their liberty by a public authority.’’ The visiting committee can then make private recommendations to the government, which will be made public if the recommendations go unheeded. This regional commitment to preventing torture provides support for international efforts to go further with monitoring for human rights abuses.

One area of the Convention against Torture that still needs much support to be put into effect is that addressing the issue of reparations. Article 14 of the Convention against Torture states that victims of torture ‘‘shall obtain redress, compensation, and rehabilitation from the state.’’ As of 2003, there still existed large discrepancies between this law and its implementation, and a study concluded that perpetrator impunity is currently the single largest obstacle both to the prevention of torture and to obtaining equitable reparations (Redress Trust, 2003). In most cases, torture survivors and their families do not have legal recourse or receive reparations of any kind. Although some survivors have received monetary compensation, there are no legal guarantees that torture will not recur, and survivors are not provided with rehabilitation. The paucity of data makes it difficult to quantify the number of complaints and determine whether reparation has been awarded. This is further aggravated by the fact that in many countries, torture is not an offense within domestic law, which limits the judiciary incentive to pursue and prosecute torturers.

Treatment And Rehabilitation Of Survivors

In December 1972, Amnesty International engaged health professionals to document torture as part of their effort to abolish it (Eitinger and Weisaeth, 1980). A medical group affiliated with AI established the first Rehabilitation and Research Centre for Torture Victims (RCT) in Denmark in an effort to help survivors. Their initial publication in the Danish Medical Bulletin of the characteristics of 200 survivors from many countries shed light on torture and its effects and the potential role for health providers in healing and recovery, but it also heightened awareness of the role of health professionals in torture itself (Rasmussen and Lunde, 1980). The next major step forward in torture treatment came in 1999, when an ad hoc committee presented to the UN the Manual on Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, now known as the Istanbul Protocol (Iacopino et al., 1999). The Istanbul Protocol is a set of international guidelines on how to assess torture survivors, document and investigate torture, and present findings to judiciaries. It has been promoted by the UN and various nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), such as Physicians for Human Rights, Global Lawyers and Physicians, and Amnesty International, with the goal of global implementation.

There are now 119 programs in the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Survivors (IRCT) network (International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims, 2006). The treatment movement overall contributes to the advance of human rights by (1) increasing knowledge that torture can have long-term effects contrary to what is postulated by torturers; (2) increasing awareness that torture and trauma can have intergenerational effects; (3) engaging the community in the recovery of survivors, leading to broader human rights-related activity; and (4) educating policymakers at treatment centers (Johnson, 1998).

Controversy exists as to whether the care of torture survivors should be mainstreamed or whether specialized centers should continue to operate and teach other providers and sectors of society (Gurr and Quiroga, 2001). Closing down the specialized centers would result in the loss of multidisciplinary services with expertise in engaging with the community and working with multicultural patients. However, the specialized centers cannot reach everyone in need of their services, so it is important that torture treatment centers collaborate with local hospitals and networks of general health practitioners. Through cooperation between mainstream and specialized health centers, knowledge about the identification and rehabilitation of torture survivors can be disseminated, and survivors will be more likely to receive the care they need.

Research On Torture

There are many challenges to researching torture. Although there are universal guidelines defining torture, individuals may define their experiences otherwise; for example, in some places, beatings are so commonplace that survivors of such brutality might not consider it torture. This can make it difficult to identify survivors. In addition, ethical issues arise when doing international or multicultural research. There may be limited understanding of informed consent in cultures unaccustomed to legal expectations of privacy or rights of refusal.

When research on torture occurs in a country where torture is taking place, there can be risks for both the researchers and the participants. Government operatives in some countries have harassed health professionals known to treat torture survivors (Physicians for Human Rights, 1996). If information from the study is released or leaked, the torture survivors may be exposed to risk of further abuses. Other ethical issues include the paucity of resources as an incentive for participation in studies, the power dynamics between the researcher and the participant, how the results will be used, and whether communities interviewed are benefited by their participation in research.

Research can also occur in receiving countries to which torture survivors flee for asylum. In these countries, there can be additional stressors for the survivor such as persecution, loss, bereavement, and the challenges of acculturation, all of which confound the effects of torture. In addition, when research or treatment involves extensive questioning that may simulate interrogation, there is a risk of retraumatizing the survivor.

A great deal of research is needed on the effects of torture. Quantitative studies could elicit the psychobiological mechanisms of torture, the neuropsychological effects of head injury, the coping mechanisms of survivors, and the influences of culture and gender on the response to trauma. In addition, outcomes research to develop standardized assessment instruments and analyze the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of treatment approaches could aid in the development of highly responsive and effective treatment for torture survivors (Quiroga and Jaranson, 2005).

Conclusion

Torture is a global public health problem and an abuse of human rights that requires a multiperspective approach to its prevention. Public health professionals and human rights advocates must unite. Lawyers, doctors, researchers, educators, and politicians must come together to work on every angle of this issue. Health professionals in particular are in a unique position to work for the eradication of torture and the promotion of human rights. Whether through research, education, or advocacy, public health workers have the power to provide a far-reaching response to the problem of torture.

Bibliography:

- Amnesty International (1983), (revised 2000 and 2005). Amnesty International 12-Point Program for the Prevention of Torture by Agents of the State. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/act40/001/2005/en/ (accessed December 2020).

- Amnesty International (2006) Annual Report 2006: The State of the World’s Human Rights. London: Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/pol10/0001/2006/en/ (accessed December 2020).

- Baker R (1992) Psychological consequences for tortured refugees seeking asylum and refugee status in Europe. In: Basoglu M (ed.) Torture and its Consequences: Current Treatment Approaches,1st edn., pp. 83–106. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Danieli Y (1998) International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma. New York: Plenum Press.

- Eitinger L and Weisaeth L (1980) The Stockholm syndrome. Tidsskrift for Den Norske Laegeforening 100(5): 307–309.

- Forrest D (1996) A Glimpse of Hell: Reports on Torture Worldwide. New York: New York University Press.

- Gurr R and Quiroga J (2001) Approaches to torture rehabilitation: A desk study covering effects, cost-effectiveness, participation, and sustainability. Torture 11(Suppl 1): 1–35.

- Iacopino V, Ozkalipci O, and Schlar C (1999) Manual on Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. (‘‘The Istanbul Protocol’’). Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Publications.

- International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (2006) International Instruments and Mechanisms for the Fight Against Torture: A Compilation of Legal Instruments and Standards on Torture. Copenhagen, Denmark IRCT.

- Jaranson JM, Butcher J, Halcon L, et al. (2004) Somali and Oromo refugees: Correlates of torture and trauma history. American Journal of Public Health 94(4): 591–598.

- Johnson D (1998) Healing torture survivors as a strategic advancement of human rights. Torture 8: 128–129.

- Miles S (2006) Oath Betrayed: Torture, Medical Complicity, and the War on Terror. New York: Random House.

- Mollica RF and Caspi-Yavin Y (1991) Measuring torture and torture-related symptoms. Psychological Assessment 3(2): 1–7.

- Physicians for Human Rights (1996) Torture in Turkey and its Unwilling Accomplices. Cambridge, MA: Physicians for Human Rights.

- Piwowarczyk LA, Moreno A, and Grodin M (2000) Health care of torture survivors. Journal of the American Medical Association 284(5): 539–541.

- Quiroga J and Jaranson J (2005) Politically-motivated torture and its survivors: A desk-study review of the literature. Torture 15(2–3): 1–111.

- Rasmussen OV and Lunde I (1980) Evaluation of investigation of 200 torture victims. Danish Medical Bulletin 27: 241–243.

- Redress Trust (2003) Reparation for Torture: A Survey of Law and Practice in Thirty Selected Countries. London: Redress Trust.

- United Nations General Assembly (2002) Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture or Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. New York: United Nations. https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/opcat.aspx (accessed December 2020).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2006) The State of the World’s Refugees: Human Displacement in the New Millennium. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Basoglu M (1992) Torture and its Consequences: Current Treatment Approaches. London: Cambridge University Press.

- British Medical Association (2001) The Medical Profession and Human Rights: Handbook for a Changing Agenda. London: Zed Books.

- Duner B (1999) An End to Torture: Strategies for its Eradication. London: St. Martin’s Books.

- Elsass P (1997) Treating Victims of Torture and Violence: Theoretical, Cross-Cultural, and Clinical Implications. New York: New York University Press.

- Gerrity E, Keane TM, and Tuma F (2001) The Mental Health Consequences of Torture. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Graessner S, Gurris N, and Pross C (2001) At the Side of Torture Survivors: Treating a Terrible Assault on Human Dignity. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

- Jaranson JM and Popkin MK (1998) Caring for Victims of Torture. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

- Leaning J, Briggs SM, and Chen LC (1999) Humanitarian Crises: The Medical and Public Health Response. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Peel M and Iacopino V (2002) The Medical Documentation of Torture. London: Greenwich Medical Media.

- Physicians for Human Rights (2001) Examining Asylum Seekers. Boston, MA: Physicians for Human Rights.

- Scarry E (1987) The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Stover E and Nightingale EO (1985) The Breaking of Bodies and Minds: Torture, Psychiatric Abuse, and the Health Professions. New York: W.H. Freeman.

- Suedfeld P (1990) Psychology and Torture. New York: Taylor and Francis.