View sample suicide and self-directed violence research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

According to the World Health Organization estimates, in the year 2000, suicide (815 000 victims) accounted for almost half of the violence-related deaths worldwide, followed by homicide and war-related fatalities (520 000 and 310 000 victims, respectively). In some countries, the suicide rates have increased by 60% over the last 45 years, and worldwide suicide is among three leading causes of death among adolescents and young adults aged 15–34. With a global rate of 14.5 per 100 000 population, suicide is a major public health problem. In addition to the premature loss of life resulting from a death by suicide and the physical and emotional trauma of suicide attempters, suicide has a serious impact on people who had known the deceased and on society as a whole.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Definition Of Suicide

Originally, the word suicide, founded on Latin ‘sui’ (of oneself) and ‘caedes’ (killing), was coined by Sir Thomas Browne, a philosopher and a physician, and first appeared in his Religio Medici published in 1643. As the conceptualization of suicide has changed over time, a wide range of definitions from a variety of disciplines has been proposed. Durkheim (1897), a sociologist, suggested that suicide constitutes all cases of death directly or indirectly resulting from a positive or negative act of a person who is aware of the consequences of the behavior. Usually there are four elements in the definition of suicide: A suicide has taken place if death occurs, it must be of one’s own doing, the agency of suicide can be active or passive, and it implies intentionally ending one’s own life. A World Health Organization Working Group recently proposed the definition of suicide as ‘‘an act with a fatal outcome which the deceased, knowing or expecting a potentially fatal outcome, has initiated and carried out with the purpose of bringing about wanted changes’’ (De Leo et al., 2004: 33).

Although the distinction between suicide and attempted suicide seems obvious based upon the outcome of behavior, i.e., a lethal versus nonlethal outcome, not all individuals who die by suicide have intended to die, and not all attempts are failed suicides. The result of such behaviors usually depends on the person’s degree of ambivalence (‘I want to die, help me to live’), knowledge of lethality of the chosen method and its availability, preparation, and coincidental factors (e.g., rescue). Also, intentions other than wanting to die are frequently involved, including a cry for help, interpersonal communication, or attention seeking. To underscore the fact that many seemingly suicidal behaviors are not directly associated with the intent to die, several terms have been proposed in the literature, including parasuicide, self-injury, and (deliberate) self-harm. As a result of confusion related to the problems in ascertaining the intent behind completed suicides and suicide attempts, the terms fatal suicidal behavior and nonfatal suicidal behavior, considering the physical outcome of the act, have been proposed (De Leo et al., 2004).

Suicidal ideation encompasses phenomena ranging from passive suicidal ideation (e.g., death thoughts and wishes: Life is not worth living or life is a burden) to active suicidal ideation and planning, which might lead to actual suicidal behavior.

Self-mutilation, i.e., direct and deliberate destruction or alteration of body tissue (e.g. skin cutting or burning, head banging, hair pulling) is a relatively common form of self-directed violence; however, its defining feature is a lack of any conscious suicidal intent. Instead, such behaviors might aim at reducing distress and anxiety, communicating anger and self-abhorrence, or coping with dissociation and traumatic memories, and there is general consensus that self-mutilation should not be included in the category of suicidal behaviors.

Epidemiology Of Suicidal Behavior

Suicide

Although there is scarcity of data regarding the prevalence of suicide in some parts of the world (including many nations in Africa, Asia, and the Western Pacific), the available epidemiological data show that suicide rates, although quite stable nationally from year to year, differ considerably among countries. Many Eastern European countries report the highest suicide rates in the world, including Lithuania (38.6 per 100 000 in 2005), Belarus (35.1 per 100 000 in 2003), the Russian Federation (34.3 per 100 000 in 2004), and Latvia (24.5 per 100 000 in 2005). High rates have also been reported in other European countries (e.g., 28.1 per 100 000 in Slovenia in 2003, 22.4 per 100 000 in Hungary in 2005, and 20.3 per 100 000 in Finland in 2004), and some Asian countries, including Japan (25.5 per 100 000 in 2003) and the Republic of Korea (25.2 per 100 000 in 2004).

Low suicide rates are found mainly in South American, African, and some Mediterranean countries, for example 5.6 per 100 000 in Italy in 2004, 5.3 in Spain in 2004, and 4.0 per 100 000 in Brazil in 2000. Other countries in Europe, North America, Asia, and the Pacific report moderate suicide rates ranging from 8.1 per 100 000 in England and Wales in 2005, 10.4 per 100 000 in Australia in 2004 and 10.8 per 100 000 in 2003 in the United States, and 15.9 per 100 000 in Poland in 2004.

The prevalence of suicide differs by age and gender. Suicide rates tend to increase with age, with the global suicide rate among those aged 75 and over (especially for males) being approximately three times higher than the rate among youth under 25 years of age. Between 1970 and 2000, an increase in suicide in young adults aged 19–24 and a decline in suicide rates among the elderly has been observed in a number of countries, especially in the Anglo-Saxon nations, including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. Contrary to this, in most Southern European, Latin American, and some Asian countries, suicide rates in old age have presented with less favorable trends and have significantly increased over the last 30 years.

In all nations of the world (except for China) suicide rates are higher in men than in women and, on average, there are three male suicides for every female suicide. The gender ratio of suicide tends to increase with age, up to approximately 12:1 among those over the age of 85. In China, in 2003, the female suicide rates were almost equal to male rates in the urban areas (11.0 per 100 000 vs. 10.9 per 100 000) but exceeded the male rates in rural areas (i.e., 17.4 per 100 000 vs. 15.1 per 100 000).

Attempted Suicide And Suicide Ideation

Fatal and nonfatal suicidal behaviors exhibit opposite tendencies with respect to age: While suicide rates peak in the elderly in most nations, attempted suicide decreases with advancing age virtually everywhere. In the elderly, estimated ratios between attempts and completions vary from 4:1 to 2:1, but in the young they can reach the level of 100–200:1. In contrast to the sex difference in completed suicides, generally there is a higher rate of attempted suicide in women than in men. An international study of nonfatal suicidal behavior in Europe, based upon data on hospital admissions, showed that the attempted suicide rates vary considerably between countries for both gender groups (Schmidtke et al., 2004). For example, the rates of nonfatal suicidal behavior among males ranged from 46 per 100 000 in Spain to 327 per 100 000 in Finland, and from 72 per 100 000 in Spain to 542 per 100 000 in France for females.

Studies based upon the general population indicate that the actual numbers of people engaging in nonfatal suicidal behavior might be even higher, as only a majority of individuals attempting suicide suffer from physical injuries serious enough to seek medical assistance and thus be admitted to hospital. International studies show that between 3% and 5% of individuals in the general population have made a suicide attempt at some time in their life with the ratio of female to male attempters between two and three to one (Weissman et al., 1999). Suicidal ideation is more frequent than attempted or completed suicide and international data indicate that approximately 10–18% of individuals in the general population have ever thought about suicide (Weissman et al., 1999), with the rates declining with increasing age.

Suicide Risk Factors

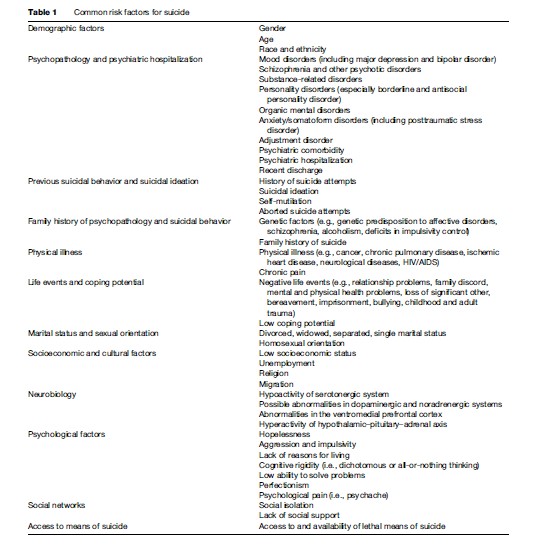

Suicidal behavior results from complex interactions between a wide range of risk and protective factors encompassing the entire life span of an individual. Characteristics increasing the likelihood of an individual becoming suicidal can be divided into distal and proximal risk factors. The distal risk factors (e.g., psychopathology, genetic and neurochemical factors) are necessary but not sufficient for suicide, and although they form the foundations for suicidal behavior, they may not obviously occur immediately prior to suicide. On the other hand, the proximal risk factors (e.g., negative life events, availability of lethal means) can be considered as triggers or precipitants of suicidal behavior; however, they are neither sufficient nor necessary for suicide to occur. It is the combined action between distal and proximal risk factors that might result in suicidal behavior.

While estimating suicide risk in an individual, one has to be wary of the ecological fallacy, or a logical error in the interpretation of statistical data, in which conclusions about individuals are based upon aggregate statistics collected for the group to which those individuals belong. For example, based upon epidemiological data, it might be incorrectly assumed that a male, a widowed, or an elderly person automatically is at increased risk of suicide. It may also be wrongly assumed, based upon data indicating that the majority of individuals who die by suicidesuffer from a mental illness, that all persons who engage in suicidal behavior are mentally ill (one of the common myths about suicide) (Table 1).

Demographic Factors

Demographic factors, including gender, age, race, and ethnicity, provide a general indication of those groups in the general population that are at the highest risk of suicide. As indicated in almost all countries, the risk of suicide is greater among males than females, and globally for both genders the suicide risk increases with age.

The prevalence of suicide also varies across racial and ethnic groups. In the United States, the prevalence of suicide among Caucasians is approximately twice that observed in all other races, and American Indian and Alaska Natives have the highest suicide rates of all ethnic groups in the country. In Australia, suicide among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has increased dramatically from low rates in the late 1980s to levels substantially higher among young indigenous males than among their nonindigenous counterparts (Hunter and Milroy 2006). For example, in Queensland, where a very accurate Suicide Register is in operation, the global rate of indigenous people is 24.6 per 100 000, which is almost twice as high as the general population rate of 15.0 per 100 000 in 2002–2004. The elevated suicide rates are particularly marked in the younger age groups: In 25to 34-year-old males (108.0 per 100 000), the suicide rate was almost three times that of the Queensland rate (39.3 per 100 000).

Psychopathology And Psychiatric Hospitalization

A diagnosis of a mental disorder, especially affective disorders, substance-related disorders, and schizophrenia, is one of the strongest risk factors for suicide, with psychiatric comorbidity (e.g., depressive disorder and substance abuse) increasing the risk even further. Studies indicate that between 88% and 99% of suicides (for general population subjects and psychiatric inpatient populations, respectively) have a diagnosis of one psychiatric disorder. However, only a relatively small proportion of individuals with major psychopathology take their own lives, and thus psychiatric disorders alone are not sufficient predictors of suicide; other factors, including the quality and availability of mental health services and effective treatment, and the individual’s social support and hopefulness, play a very important role. Periods of psychiatric hospitalization tend to increase the risk of suicide, and after discharge, suicide risk is significantly increased within the first weeks and remains elevated for up to 6 months.

Although persons with practically any mental illness engage in suicidal behaviors more often than individuals in the general population, the diagnoses most frequently related to suicidal behaviors include mood disorders (including major depression and bipolar disorder), schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, substance-related disorders, personality disorders (especially borderline and antisocial personality disorder), anxiety/somatoform disorders (including posttraumatic stress disorder), and adjustment disorder.

Increased risk of suicidal behavior is related to both depression as a mental disorder and depressive symptoms occurring in the course of other psychiatric illnesses (e. g., schizophrenia, substance abuse, personality disorders) and severe and chronic medical conditions (e.g., cancer, HIV/AIDS). Among patients with affective disorders, suicide risk is higher among inpatients hospitalized following suicidal ideation or attempt, and lower in inpatients admitted for an affective disorder or in depressed outpatients.

There are limited data on suicide risk in people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder; however, it seems that there is no substantial difference between suicide risk in unipolar and bipolar major affective disorders. Both are related to elevated risk for fatal and nonfatal suicidal behaviors and between 25 and 50% of people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder attempt suicide, with up to 20% of individuals in this group dying by suicide. People suffering from bipolar disorder are also at increased risk of premature mortality related to cardiovascular disease and compromised health during the manic phase (e.g., sleep deprivation, malnutrition, and substance abuse).

Between 10 and 15% of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia die by suicide, between 18 and 55% make a suicide attempt in their lifetime, and 60–80% experience lingering suicidal thoughts. Individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia seem to be at a particularly high risk of suicide in the first 10 years of illness onset, and psychiatric comorbidity (e.g., schizophrenia and depressive disorder or substance abuse) increases the risk of suicide. Patients with schizophrenia are also at extremely high risk of inpatient suicide.

Approximately 2–4% of individuals with an alcohol use disorder die by suicide, and comorbid psychiatric conditions (especially depression and anxiety disorders) significantly increase the risk. The evidence for the association between alcohol abuse and nonfatal suicidal behavior is less consistent, although studies indicate that up to 30% of individuals who attempt suicide cited alcohol addiction as the reason for their attempt. Also, abuse of other substances is related to high incidence of nonfatal and fatal suicidal behavior, although the clinical picture in such cases is often complicated by polysubstance (drug/ alcohol) abuse. An increased suicide rate was found in narcotic and opioid addicts, with up to 7% of cocaine abusers and up to 35% of heroin users dying by suicide.

Previous Suicidal Behavior And Suicidal Ideation

A history of a suicide attempt is a major risk factor for both repeated nonfatal suicidal behavior and suicide. Almost one in four suicide attempters makes another nonlethal attempt within 1 year, with the highest risk observed during the first 3–6 months after the initial attempt. Approximately 1% of attempters kill themselves within 1 year after the attempt, and 3–5% (some studies report even higher numbers: up to 13%) over the 5–10 years after the initial attempt (Owens et al., 2002).

Although suicide ideation in the general population is a quite frequent phenomenon, it might lead to a detailed suicide plan resulting in self-harming behavior and suicide. A general population study in the United States showed that suicide ideators with a plan are more likely to attempt suicide than those without a plan, i.e., impulsive suicide attempters (Borges et al., 2006). However, the absence of a suicide plan does not mean the absence of suicide risk; almost half of attempts reported in the study were unplanned – the suicidal behavior occurred without a plan conceived prior to the situation that triggered the suicidal behavior.

The acts of self-mutilation characterized by lack of conscious suicidal intent are usually distinguished from suicidal behaviors; however, individuals who self-mutilate, particularly patients with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, might be at increased risk of suicide. Also, individuals with a history of an aborted suicide attempt (i.e., an event without physical injury in which an individual has suicide intent but changes his or her mind before making the attempt) might be at increased risk of actual suicidal behavior. A study on the prevalence of suicidal behavior among psychiatric inpatients showed that there were almost twice as many suicides among patients with aborted attempts as among patients without aborted attempts (Barber et al., 1998).

Family History Of Psychopathology And Suicidal Behavior

Different lines of evidence point to the possibility of familial or genetic determinants of suicidal behavior. Clinical and follow-up studies show that individuals with a diagnosis of a mental disorder (especially depression) and a history of suicidal behavior and affective disorder among the first and second-degree relatives have increased risk of engaging in suicidal behavior themselves. These data are supported by results of twin and adoption studies showing the statistically significant higher incidence of suicide and psychiatric disorder in monozygotic pairs than among dizygotic twins, and among biological relatives of suicides than among the adoptive parents.

Several explanations concerning the familial vulnerability to suicide have been offered. Genetic factors related to suicide may mostly represent a genetic predisposition to psychiatric illness, including affective disorders, schizophrenia, and alcoholism, as well as deficits in impulse control. In addition, the mechanism of social modeling may play an important role: The family member(s) who dies by suicide may serve as a role model(s), pointing to suicide as the best and acceptable solution to life problems.

Physical Illness

Between 30 and 40% of people who die by suicide have a diagnosis of a medical illness, and the number escalates to almost 90% among the elderly victims of suicide. There is documented evidence that cancer, chronic pulmonary disease, ischemic heart disease, neurological diseases (e.g., epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Huntington’s chorea, and stroke), and HIV/AIDS are associated with elevated suicide risk. Also rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes (especially juvenile diabetes), and neoplasms of the cervix and prostate may be related to increased suicide risk.

Medical disorders are associated with suicide in various ways: Some medical disorders may be caused by self-injury or substance abuse stemming from preexisting mental disorders, and a medical disorder and treatment (e.g., medication) may affect brain functioning, leading to personality disorders and mood disturbances. Disfigurement or disability caused by medical illness may result in mood dysregulation, and stigmatized diagnoses may contribute to social isolation and withdrawal. Also, chronic physical pain is a recognized risk factor for suicidal ideation and behavior.

Life Events And Coping Potential

Individuals who attempt or commit suicide experience more stressors and negative life events than individuals in the general population (especially in the month prior to suicide). Among the life stressors most often found in histories of suicidal individuals are relationship problems, family discord, mental and physical health problems, loss of a significant other, bereavement, imprisonment, and work problems (Ko˜lves et al., 2006). There is a positive correlation between an individual’s history of childhood sexual and/or physical abuse and suicidality, and adult traumas (e.g., rape, torture, military combat) may be related to elevated suicide risk.

Life stresses can be important proximal risk factors triggering suicidal ideation and behavior; however, only a minority of individuals faced with life adversities and negative life events become suicidal. Such events must be placed within the context of life-long coping patterns, personality structure, availability of social support and willingness to ask for help, and other distal risk factors, including psychopathology.

Marital Status And Sexual Orientation

There is a strong association between marital status and suicide: Divorced, widowed, and separated persons have the highest suicide rates, while married people have lower suicide rates than never married individuals. Marriage and responsibilities for bringing up children may serve as a protective factor against suicide by reducing social isolation, providing emotional and social stability, and enhancing social integration. Males, especially in the first few months after marital loss or separation, seem to be particularly vulnerable and at increased risk for suicide.

Although completed suicide rates do not appear to be increased among homosexual men and women, there is a greater lifetime prevalence of nonfatal suicidal behavior in these populations, especially among homosexual adolescents and young adults. The factors that may exacerbate the risk of suicidality in these populations include limited sources of support, stress in interpersonal relations, discrimination, abuse of drugs and alcohol, and anxiety about HIV/AIDS.

Socioeconomic And Cultural Factors

Sociological studies have consistently found a correlation between low socioeconomic status and suicide rates, although there are some high-status occupations with increased suicide risk, e.g., dentists, physicians, and veterinarians (Stack, 2000a). Unemployment is often considered as a major risk factor for suicide, especially among men. Studies at both aggregated and individual level indicate that unemployment is directly correlated with suicidality, although the nature of the relationship between those two phenomena has not been fully explained. For example, job loss (and related loss of income and status) or inability to find work over an extended period of time might act as a proximal triggering factor for suicide. Personal vulnerabilities (including psychopathology) might mediate between the unemployment status and suicidality in a more complex and two-directional way (Stack, 2000).

Religion is an important factor impacting on the prevalence of suicidal behavior. Lower suicide rates have been reported in countries where major religious beliefs include sanctions against suicide, for example countries that are predominantly Muslim or Roman Catholic. At the individual level, religiosity might protect against suicide through the content of religious beliefs (e.g., after-life sanctions against killing oneself); however, its positive correlation with levels of social integration and social support through church attendance and networks with others who share the same beliefs seems to have a stronger impact (Stack, 2000).

The impact of cultural factors on suicide rates can effectively be illustrated by studies on migrants. Such studies have been carried out predominantly in countries with a significant influx of migrants, including the United States, Australia, and Canada. In these countries, suicide rates among diverse migrant groups tend to reflect the rates of their countries of origin; however, a trend of convergence toward the rates of the host country has been observed over time in the United States, the UK, Australia, and Scandinavia. It has also been suggested that the migrant status could increase the risk of suicide in vulnerable individuals (especially those with preexisting psychopathology, people who were forced to leave the country of origin or experienced a downgrading in social status as a result of the move) due to acculturation stress, social isolation, and language barriers (Stack, 2000).

Neurobiology

Research in the area of neurobiology of suicidal behavior has repeatedly shown that suicide attempters and completers have decreased levels of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (a metabolite of serotonin) in the cerebrospinal fluid when compared to depressed subjects and nonclinical controls. Decreased serotonergic function has also been reported in studies using the fenfluramine challenge and observing a decreased prolactin response. The relationship between the hypoactivity of the serotonergic system and suicidality seems to be mediated by lethality of attempts, aggression, and impulsivity ( Joiner et al., 2005).

Suicidal individuals show neuroanatomical abnormalities in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which may correlate with the neurochemical deficits found in this population, and individuals who made a highly lethal suicidal attempt show decreased prefrontal cortex functioning. Although the results are still inconclusive, it has been suggested that abnormalities in other neurotransmitter systems (i.e., dopaminergic and noradrenergic systems) and hyperactivity of other brain systems, such as the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, may be involved in suicidal behavior, and there is also a suggested relationship between low levels of cholesterol and suicidality, although the mechanism of the association remains unclear ( Joiner et al., 2005).

Psychological Factors

Psychological characteristics or vulnerabilities of individuals might exacerbate the impact of other risk factors (including psychopathology, negative life events, social factors) and thus increase the risk of suicide. Hopelessness (i.e., a state of negative expectancies concerning oneself and one’s future) is one of the strongest predictors for suicidal ideation and behavior, stronger even than depression itself. Studies have established that hopelessness may predict as many as 91–94% of suicides in both outpatient and inpatient populations (Beck et al., 1990). Other psychological and cognitive risk factors for suicide include aggression and impulsivity, lack of reasons for living, cognitive rigidity (i.e., dichotomous or all-or-nothing thinking), poor problem-solving capabilities, and perfectionism ( Joiner et al., 2005). Also, the experience of psychological suffering and pain (or psychache) is a strong correlate of elevated suicide risk.

Social Networks

Isolation and lack of social support have been related to many aspects of psychopathology, including ineffective coping with stress and life crises. Suicidal individuals are often described as isolated and alienated from their families and communities, and bereft of emotional and instrumental social support and other resources. This may be due to adverse life circumstances or individuals’ inability to maintain satisfactory interpersonal networks. Loneliness may lead to depression and emotional distress or increase their severity, as well as exacerbate the effects of negative stressors. Moreover, isolated and lonely individuals are at higher risk of death when they engage in suicidal behaviors, as the chances of lifesaving intervention by others are severely reduced or nonexistent.

Access To Means Of Suicide

Almost all methods used by individuals engaging in suicidal behaviors may lead to death or serious injuries; however, the statistical probability of death as a result of a suicide attempt varies between methods. The choice of means of suicide depends on several factors, including availability of the method, the individual’s familiarity with the method, the intent and motivation behind the behavior, the degree of ambivalence, and cultural factors (e.g., gender socialization, symbolic meanings of suicide methods).

The choice of more lethal suicide method by males as compared to females might in part explain the differences in suicide rates among genders. Older individuals (usually characterized by a higher intent to die) tend to choose more lethal methods than their younger counterparts. Also, there are international differences regarding suicide methods used most frequently. For example, in the United States guns are used in approximately two-thirds of all suicides, while hanging is the most frequent method in all other Western nations. In a number of developing countries, pesticide poisoning is the most common cause of suicide mortality; in many areas of China and South East Asia, suicide by pesticide ingestion accounts for 60% of all suicides (Gunnell and Eddleston, 2003).

Protective Factors

Sufficiently strong protective factors can outweigh the impact of risk factors and reduce the risk of suicide. Although this area of study is still in its infancy, several protective factors have been identified. These include family and nonfamily social support, significant and stable relationships (including marriage), children under the age of 18 living at home, physical health, hopefulness, reasons for living, problem-solving and coping skills, cognitive flexibility, plans for the future, constructive use of leisure time, the propensity to seek treatment and maintain it when needed, religiosity, culture and ethnicity, employment, and restricted access to lethal means of suicide.

Prevention Of Suicide, Treatment, And Postvention

Suicide is a complex, multidetermined behavior and it would be unrealistic to expect that any single preventive effort could reduce an individual’s risk of suicide and the overall suicide mortality rates. In general, the preventive efforts that have been initiated in a number of multidisciplinary settings operate to target risk factors for suicide and to strengthen the protective factors.

Traditionally, there are three levels of prevention with regard to suicide: Universal, selective, and indicated prevention. Universal prevention refers to activities targeted at the general population, including health promotion and education, which may improve the overall emotional and social well-being of individuals, and may target suicide risk factors. Selective prevention refers to interventions aimed at populations identified as being at risk of suicide, while indicated strategies address specific high-risk individuals showing early signs of suicidality. A wide variety of suicide prevention approaches have been developed across the three domains: Treatment of mental disorders and pharmacotherapy, behavioral and relationship approaches, community-based efforts (including suicide prevention centers and school-based interventions), societal approaches including restricting access to suicide means and improved media reporting of suicide, as well as interventions for people bereaved by suicide (i.e., suicide survivors). In 1996, the United Nations issued a document stressing the importance of a guiding policy on suicide prevention: ‘Prevention of suicide: Guidelines for the formulation and implementation of national strategies.’ Subsequently, in 1999, the WHO launched a worldwide initiative for the prevention of suicide (SUPRE Project).

In some countries, such as Australia, New Zealand, Finland, Norway, Sweden, England, and the United States, comprehensive national suicide prevention strategies have been implemented over the last two decades. Such strategies usually aim at improving detection and treatment of mental disorders (particularly depression) and substance abuse and enhancing access to mental health services. Their goals also include reducing access to lethal means of suicide, improving responsible reporting of suicide in the media, enhancing support for those bereaved by suicide, educating the general public and health-care professionals, and setting up school-based suicide prevention initiatives. Although some components of the strategies may be effective in reducing the risk of suicide, to date there is no evidence for an overall positive impact of the national strategies (with the possible exception of Finland) on countries’ rates in the 5 years following their implementation (De Leo and Evans, 2004).

International studies looking at the effectiveness of a range of suicide prevention approaches indicate that restricting access to lethal methods and educational programs for physicians that improve their skills in recognition and treatment of depression reduce suicide rates. More data and more studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of other types of interventions, including screening programs, media reporting guidelines, and public education campaigns.

A wide variety of psychosocial treatments for suicidal individuals or patients who have attempted suicide have been developed, including a dialectic and cognitive behavioral approach, a psychodynamic model, problem-solving therapy, multimodal interventions, family interventions, inpatient treatment, and pharmacotherapy (e.g., antidepressants). Unfortunately, despite a large number of studies looking at the effectiveness of such interventions, to date there is only limited evidence regarding recommended treatments for patients at risk of suicidal behavior and its repetition (Hawton et al., 2004). Brief psychological interventions (including problem-solving therapy) and dialectic behavioral therapy for women with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder seem to be effective treatment options. There is also limited evidence supporting the effectiveness of follow-up and active out-reach (e. g., by home visits or telephone contact) with patients with a history of a suicide attempt who do not attend therapy appointments. Despite many studies, the role of antidepressants in reducing the risk of suicide remains unclear.

Suicide prevention initiatives also include post vention aimed at survivors of suicide, or family members, friends, and other individuals who knew the person who died by suicide and were affected by the death. Although not everyone who experiences loss by suicide requires specialized psychological help, for some it might lead to a serious crisis calling for professional psychotherapy or support from others who have experienced a similar loss. The majority of national suicide prevention strategies aim at enhancing the support available for those bereaved by suicide, and in many Western countries (such as the United States, Western Europe, and Australia) numerous self-help, support, and therapy groups for suicide survivors have been developed.

Conclusions

Although much progress has been made in the field of suicide research and prevention over the decades, many unanswered questions remain on what is really effective in preventing suicide at both the individual and societal levels. Among the greatest challenges is collection of epidemiological data regarding the suicide-related morbidity and mortality around the world and encouraging research in many countries outside the Western (mostly English-speaking) environment. Also, multidisciplinary studies looking at risk and protective factors in suicidal behaviors will allow for further insights into the dynamics of suicidality and should enhance development of innovative and effective prevention strategies.

Bibliography:

- Barber ME, Marzuk PM, Leon AC, and Portera L (1998) Aborted suicide attempts: a new classification of suicidal behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry 155: 385–389.

- Beck AT, Brown G, Berchick RJ, et al. (1990) Relationship between hopelessness and eventual suicide: A replication with psychiatric inpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 147: 190–195.

- Borges G, Angst J, Nock MK, et al. (2006) A risk index for 12-month suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Psychological Medicine 36: 1747–1758.

- De Leo D and Evans R (2004) International Suicide Rates and Prevention Strategies. Go¨ ttingen: Hogrefe & Huber.

- De Leo D and Spathononis K (2003) Do psychopharmacological and psychosocial treatments reduce suicide risk in schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders? Archives of Suicide Research 7: 354–373.

- De Leo D, Burgis S, Bertolote JM, et al. (2004) Definitions of suicidal behaviour. In: De Leo D, Bille-Brahe U, Kerkhof ADJF and Schmidtke A (eds.) Suicidal Behaviour. Theories and Research Findings, pp. 17–39. Go¨ ttingen: Hogrefe & Huber.

- Durkheim E (1897) Le Suicide. Paris: Felix Alcan. English version (1951) Suicide. New York: Free Press.

- Gunnell D and Eddleston M (2003) Suicide by intentional ingestion of pesticides: A continuing tragedy in developing countries. International Journal of Epidemiology 32: 902–909.

- Hawton K, Townsend E, Arensman E, et al. (2004) Psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for deliberate self-harm. The Cochrane Library. Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001764. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. CD001764.

- Hunter E and Milroy H (2006) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander suicide in context. Archives of Suicide Research 10: 141–157.

- Joiner TE, Brown JS, and Wingate LRR (2005) The psychology and neurobiology of suicidal behavior. Annual Review of Psychology 56: 287–314.

- Owens D, Horrocks J, and House A (2002) Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. British Journal of Psychiatry 181: 193–199.

- Schmidtke A, Weinacker B, Lo¨ hr C, et al. (2004) Suicide and suicide attempts in Europe. An overview. In: Schmidtke A, Bille-Brahe U, De Leo D and Kerkhof ADJF (eds.) Suicidal Behaviour in Europe. Results from the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Suicidal Behaviour, pp. 15–28. Go¨ ttingen: Hogrefe & Huber.

- United Nations (1996) Prevention of Suicide: Guidelines for the Formulation and Implementation of National Strategies. New York: Department of Policy Coordination and Sustainable Development.

- Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. (1999) Prevalence of suicide ideation and suicide attempts in nine countries. Psychological Medicine 29: 9–17.

- De Leo D, Bertolote JM, and Lester D (2002) Self-directed violence. In: Krug EG, Dahleberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB and Lozano R (eds.) World Report on Violence and Health, pp. 183–212. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- De Leo D, Bille-Brahe U, Kerkhof A, and Schmidtke A (eds.) Suicidal Behaviour. Theories and Research Findings. Go¨ ttingen: Hogrefe & Huber.

- Jacobs DG (ed.) (1999) The Harvard Medical School Guide to Suicide Assessment and Intervention. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Hawton K (ed.) (2005) Prevention and Treatment of Suicidal Behavior. From science to Practice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Hawton K and Van Heeringen K (eds.) (2000) The International Handbook of Suicide and Attempted Suicide. Chichester, UK: Wiley & Sons.

- Lester D (ed.) (2001) Suicide Prevention. Resources for the Millennium. Philadelphia, PA: Brunner-Routledge.

- Maris RW, Berman AL, and Silverman MM (eds.) (2000) Comprehensive Textbook of Suicidology. New York: Guilford Press.

- Van Heeringen K (ed.) Understanding Suicidal Behavior. The Suicidal Process, Approach to Research, Treatment and Prevention. Chichester, UK: Wiley & Sons.

- https://suicidology.org/ – American Association of Suicidology.

- https://afsp.org/ – American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

- https://crise.ca/en/ – Centre for Research and Intervention on Suicide and Euthanasia.