View sample public health research paper on planning for public health policy. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Health Planning – What Is It?

Definition Of Health Planning, Overall Purpose Of Planning, Relationship To Policy Making

Health planning can be defined as: ‘‘a systematic approach to attaining explicit objectives for the future through the efficient and appropriate use of resources, available now and in the future’’ (Green, 2007: 3).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Many definitions of planning focus on technical aspects such as setting goals, outlining broad strategies and developing detailed activities. Health planning, however, also involves the art of maneuvering between different actors and processes in the context of the health system to achieve desired objectives. It is thus also a political process and one that involves real choices between alternatives, each with different technical and political advantages and disadvantages. The need for planning arises from the shortfall between the available resources and the resources needed to address the perceived health needs that face health systems. This highlights the importance of prioritization as a key feature of health planning.

Health planning can be perceived as a continuation of health policy-making, i.e., translation of policy outputs (statements, documents) into implementation strategies and plans. This ‘operationalization’ of policy outputs can occur at different levels of a country’s health system (e.g., national, regional) and result in different types of plans (e.g., strategic plan, rolling operational plan). Health planning and health policy making are both often described as cycles with clearly defined stages and continuous nature of the process.

A distinction needs to be made between health planning and health-care planning. The former recognizes the wider determinants of health and the need for multisectoral initiatives while the latter focuses on health services. This research paper assumes the first, broader scope.

Planning can be interpreted as an attempt to address the following questions:

- Where are we now?

- Where do we want to be?

- How are we going to get there?

Different types of planning focus on different aspects of these questions. For example, strategic planning, which is often seen as an integral part of health policy making, is concerned with defining the priority direction for the development of a sector or a program (the second question). In contrast with this, operational planning is more concerned with the technicalities of the process, as in the third question.

The purpose of planning should not be seen as merely the production of plans, but also their implementation. As such it includes monitoring and evaluation, which lead to the next cycle of the planning process. Planning is therefore closely linked with both policy making and management. Health planning is also concerned with negotiating priorities and strategies between key actors, which reinforces its links with health policy making.

Historical Roots

Although planning is sometimes described as having emerged as a discipline in industrialized countries after World War II (Rodwin, 1984), it can be argued to have existed earlier. For example, John Snow is often regarded as the father of modern epidemiology, and there are certainly elements of health planning in his work; the Soviet Union introduced 5-year national development plans in 1928 and India has developed national development plans since 1951. Planning is a separate discipline in virtually every sector including health. Furthermore, planning is embedded into almost every aspect of the health system ranging from planning of an individual patient’s treatment course to planning sector development for the next decade.

Health Planning – The Main Features

While the rationale for planning (the need to make choices about the use of scarce resources) is common to planning in all sectors, there are some distinctive features to health planning. Health is a very labor-intensive sector with the time needed to train a health professional often being several years. As such long-term human resource planning is critical for the health sector.

A second feature of health planning is the complex power relations between the various actors involved in or influencing decision-making processes. This includes both external (donors, international agencies) and internal (health ministry, professional associations, civil society) stakeholders. Health planning, because of close links with health policy making, is seen as both a technical and a political process with different groups of stakeholders bringing different agendas into the process. Mechanisms of engagement and the degree of influence of various actors may vary (for instance, some may impose conditionality, whereas others may use advocacy as the main instrument of influence). Complex interrelationships between different groups of stakeholders can have an impact on the approaches to, and success of, health planning.

A third characteristic of health planning is the tension between the clinical perspective (focus on individuals) versus the public health perspective (focus on populations). Planning within the health system needs to find an accommodation between both perspectives.

Values In Planning

The technical basis of planning suggests the need for rationality of approach, efficiency, and the use of evidence to support decisions. One important issue in health planning relates to objectivity. While the use of evidence in the planning process is essential, it is also important to recognize both that information or evidence may not be available or reliable and that selection and interpretation of information can also reflect particular values and judgments. Indeed, all parts of the planning process involve values. Key ones are those related to equity, gender, human rights, solidarity, and wider choice to patients and communities. Different stakeholders will, of course, have different ideological perspectives and values.

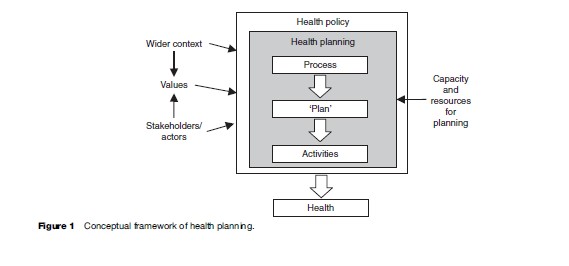

Figure 1 provides a conceptual framework for the planning system showing the relationships of the processes, actors, values, and the wider context.

Each factor resulting from the above elements of the conceptual framework affects the broad approach to planning, use of evidence in the planning processes, as well as the other context-specific characteristics of health planning such as the choice of priorities.

Health planning occurs at different organizational levels of the health system. Priorities and values may differ at the national level from those at the local level.

Links Between Planning And Other Decision-Making Processes

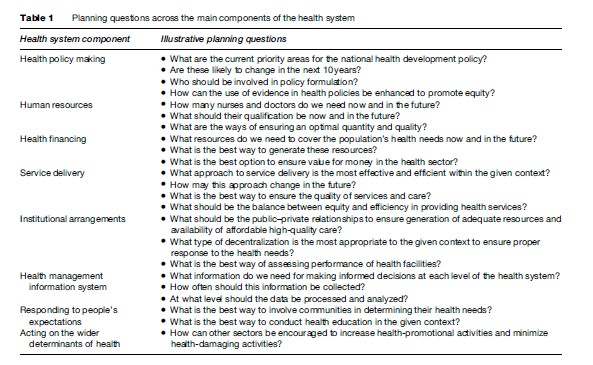

For planning to function effectively, it needs to be embedded in all the decision-making processes within the health sector. Most planning failures can be traced to a lack of consistency between these different systems. This is exemplified in Table 1 with illustrative planning questions across the main components of the health system.

Questions for planning vary, depending on the level of the health system. For example, national-level policy makers may be more concerned with the priority areas for a country’s overall health policy and the availability of resources including professional staff, while the primary planning issue for local decision makers would be how to ensure an adequate response to the policy direction in terms of service provision.

The need for planning and the type of planning decisions at each level of the health system also depend on the degree of autonomy and wider decision-making practices in society. For example, if budgeting is seen as a bottom up process the role of the national level will be to respond to locally identified needs, while if the health system is highly centralized and hierarchical, the local level is likely to follow nationally set directives.

Who Should Plan

Health planning should be a shared task at all levels of the health system. Planning is, however, often seen as the responsibility of a separate administrative unit. But planning is wider than this and requires constant interaction between decision makers, managers, and professionals at all levels. This suggests the need for input into planning by decision makers at each health system level with the planning unit performing advisory and facilitatory functions and guiding decisions from a technical perspective. The ultimate decisions would be made by relevant stakeholders such as community leaders, patients, and health professionals.

The Context Of Health Planning

Health planning occurs within the political and socioeconomic context involving complex links between the wider societal factors and health planning processes. Key contextual factors include:

- stage of development of a particular country (for example, countries in transition);

- power of different groups directly or indirectly involved in the decision-making process;

- historical decision-making processes;

- resource framework;

- available planning expertise and skills;

- institutional arrangements for implementing plans.

The context in which planning takes place is everchanging. In particular, the health pattern is changing due to a complex set of factors including demographic and epidemiological transition and the emergence of new diseases such as HIV/AIDS or avian flu; public sector (including health) systems may be reformed; costs are rising and the expectations of users are growing. These and other important factors set the complex contextual environment for health planning.

Planning has moved away from ‘‘…intuitive, spontaneous, and subjective projection of activity based on past experience to a much more deliberate, systematic and objective process of mobilizing information and organizing resources’’ (Reinke, 1988: 3).

Changing Environment

Objectives for health planning may change as health systems develop. One can observe emphasis on different aspects of health and health system at different times. For example, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, efforts were directed mainly toward responding to epidemics and focusing on wider determinants of health, building health systems, and developing health (social) insurance (Hyman, 1982); until the mid-1960s, planning largely focused on managing growth of the health sector; in the 1970s and 1980s, planning efforts were concentrated on improving access to health services and the 1990s were characterized by health sector reforms. New issues for national health planning include integration of global vertical health programs with national health systems and a return to wider social determinants of health.

Since the late 1970s, health planning has been increasingly influenced by international actors and their priorities and policies. One of the first international health planning efforts was the set of elements of the Alma Ata Declaration (Primary Health Care strengthening, Health For All by the Year 2000), which prompted development of PHC in many contexts. More recently, global targets such as the 3-by-5 initiative (treating three million people living with HIV/AIDS by 2005), which was launched by WHO and UNAIDS in 2003, and the adoption of Millennium Development Goals at the UN General Assembly in 2000 have shaped international health; this is also reflected in the increasing number of international agencies and in particular Global Public Private Partnerships such as the GAVI Alliance and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria.

Planning For Public–Private Mix And Regulatory Role Of The Government/Public Sector

Marketization of the health system was widely advocated in the 1990s and this policy encouraged a greater role for the private sector. The resultant complexity in the public– private mix suggests the need for changes in the approaches from what had often been a primary focus on public sector health services. It suggests the need to develop new planning tools suitable for inducing appropriate change in the private sector. While public-sector planning relies heavily on managerial directives and controls, planning for the private sector requires use of legislative and regulatory tools, advocacy, and the use of incentives.

Planning For Decentralization

Decentralization is another example of a changing context. This may be either part of a wider governance policy or health-sector-specific, and indeed may be part of health plans themselves.

The approach to planning will depend on the type and degree of decentralization of the health sector. For example, devolution (devolution is the most comprehensive form of decentralization, which is different from deconcentration where vertical lines of management control are retained), is likely to result in wider participation of local levels and hence bottom-up planning, and greater opportunities for multisectoral action.

An important aspect of decentralization is the process and criteria whereby central funds are allocated to lower levels. Resource allocation formulae based on needs are being increasingly introduced to replace historical incremental systems of allocation.

Planning Within Emergency And Transitional Countries

Within rapidly changing environments such as emergencies, planning is likely to concentrate on short-term objectives. One example of short-term planning objectives from a public health perspective is provision of safe drinking water to prevent water-borne infections in the wake of a humanitarian disaster.

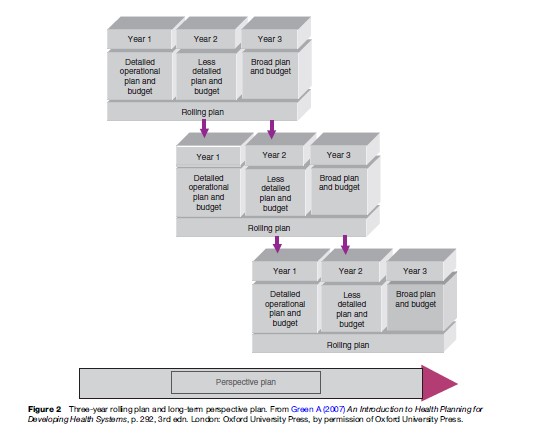

Planning within transitional countries where the situation changes faster than in more stable contexts may be best done on a rolling or incremental basis.

Technical Issues In Health Planning

In broad terms, approaches to planning can be described as being on a continuum with two extremes: Top-down and bottom-up. The top-down approach implies that the planning process occurs exclusively at the central level with only final decisions (plans) communicated to the local levels. The bottom-up approach encompasses the idea of local levels being closely involved in the planning process through assessment of health needs, identification of priorities, and participation in other planning decisions. Top-down planning is normally found in centralized systems with strong command and control mechanisms with bottom-up planning in genuinely decentralized contexts. The latter provides an opportunity for wider participation and empowerment of stakeholders in decision-making processes including planning, which stems from contemporary disillusionment with top-down processes of command and control. Each approach has its strengths and weaknesses but nowadays there is a preference at the international level for bottom-up health planning, which is partly the result of disillusionment with the effectiveness of top-down processes.

From the perspective of the level of the health system, health planning can occur at country, sector, program, or project levels. Health planning can also be described as strategic or operational. Strategic planning is an integral part of health policy, is normally broad, long-term, and associated with central levels of the health system, while operational planning is short term, more detailed and particularly relevant to the local levels of health system.

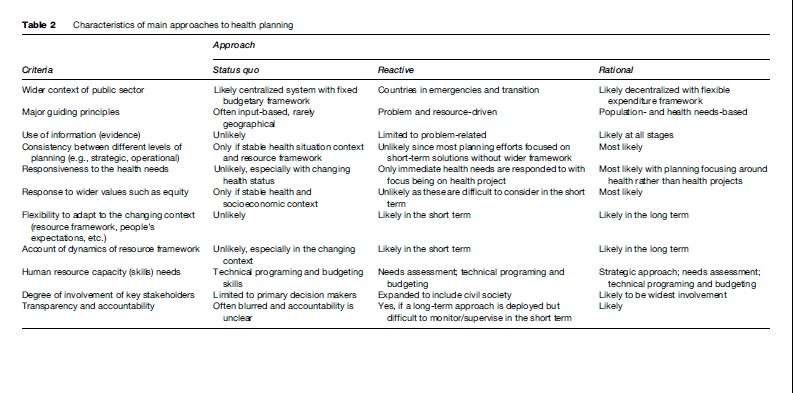

Approaches to health planning also relate to the wider decision-making styles and can be divided into three broad categories:

- status quo models, i.e., reproducing previous plans;

- reactive planning, i.e., plan only if it is regarded as necessary – this may include problem-solving approaches;

- rational proactive planning.

Characteristics of these approaches are described in Table 2. There will inevitably be intermediate approaches which contain elements from more than one approach. An example of this is incremental planning, which can be described as small adjustments to the status quo in the light of current political circumstances (Buse et al., 2005).

Forecasting can be an important part of health planning. From the health planning perspective, forecasting can be seen as a process of projecting any determinants of health planning such as future health service delivery needs for a particular population. Examples of forecasting can be seen in the models that attempt to predict future health professional requirements to respond to the health needs arising from a projected population growth and/or shifts in disease patterns. It is important to ensure that such forecasting takes account of the particular context of a health system and does not apply uncritically international blueprints.

It can, however, be difficult to differentiate between evidence-based projections/modeling , which may be part of rational planning, and blueprinting , which shares some characteristics with status quo planning. In contrast with evidence-based projections, an implicit assumption within blueprinting is that the same models (health plans) can be replicated in different contexts. In practice, however, the ever-changing environment provides just one example of the need for contextualization in health planning.

We consider rational planning, which takes account of political influences as optimal, and will focus here on the processes related to this. However, any approach inevitably has downsides and the rational approach is no exception. Some downsides include the significant human resource capacity required, the need for reliable information (evidence), and the ability of key actors to believe in results of rational approaches. It is important also to recognize that in practice the distinction between different approaches is blurred.

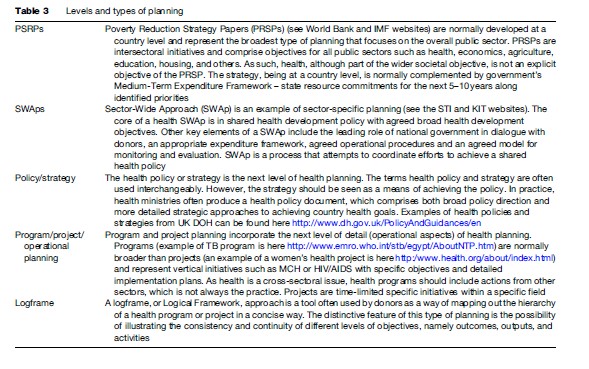

Types Of Planning

There is no general consensus on the terms for types of health planning. Different perspectives are used to classify different types of health planning. For example, some classifications follow the lines of comprehensiveprogram-project (Taylor and Reinke, 1988) where comprehensive stands for broad strategic planning and the next steps focus on operational planning. Another perspective distinguishes types of health planning across main levels of planning, e.g., national, regional, and district (Green, 2007).

Health planning is a chain of interrelated processes involving different levels of planning (country, sector, program, project). Within this, the logic of one process being translated into another is evident. This is exemplified in Table 3.

Another feature of different types and levels of planning is the time-frame. The higher the level of planning the longer the timeframe for achieving objectives. For example, Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers and Sector-Wide Approaches may be processes for 5+ years, while operational planning is usually done on an annual/semi-annual/quarterly basis.

The Rolling Plan (Figure 2) is another type of plan that emphasizes the continuous nature of health planning at the operational level.

One theme from the above is the necessity of a clear link between strategic and operational aspects of health planning. We suggest that this is two-way: Operational planning should develop implementation aspects of wider strategy and strategic planning and is an opportunity to scale up positive experience from implementation of operational plans. This is particularly true in the case of pilot initiatives, where innovative ideas are tested.

New techniques for health planning are being continuously developed, including at the international level. Marginal budgeting for bottlenecks (MBB) is an example of a new method developed by UNICEF, WHO, and the World Bank, which attempts to identify bottlenecks (factors negatively affecting implementation) and estimate the marginal cost of eliminating these. As a result of the close relationship between strategic and operational levels of health planning, MBB is seen to be a useful tool to help countries develop their Medium-Term Expenditure Frameworks and align efforts toward more effective and efficient utilization of available resources. MBBs normally comprise three components: Identification of barriers (bottlenecks), costing, and assessment of possible impact (Knippenberg et al., undated).

Stages Of The Planning Process

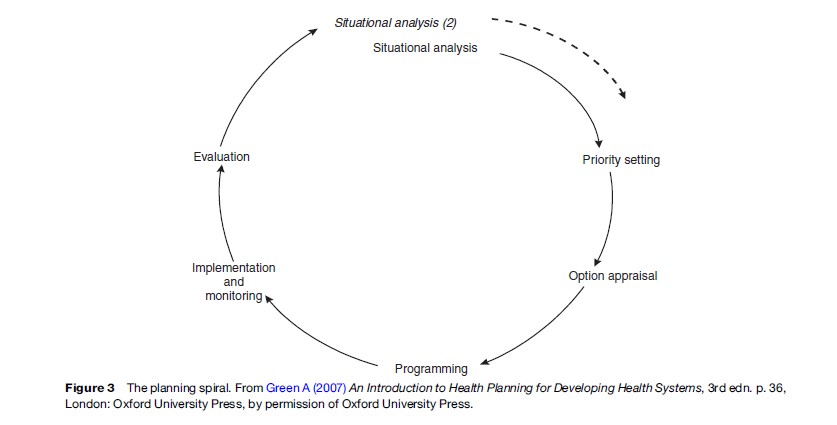

Planning processes can be illustrated in the form of a spiral. Green’s planning spiral (Figure 3) is a classical example of approaching planning from a rational–comprehensive perspective and illustrating it as a continuous process.

Green’s model includes six stages (situational analysis, priority setting, option appraisal, programing, implementation and monitoring, and evaluation). Within the public health context, these broadly correspond to the following five stages of making a decision on the best public health intervention (Walley et al., 2004):

- assessing health needs (which corresponds to situational analysis stage in the Green’s planning spiral);

- reviewing health services and programs (situational analysis and priority-setting stage);

- choosing the best interventions (option appraisal stage);

- listing the activities and drafting an action plan (programing stage);

- implementing and monitoring (implementation and monitoring and evaluation stages).

The process of health planning usually involves iteration (as exemplified by the spiral) and should not be seen as linear.

Situational Analysis

A situational analysis answers the question: Where are we now? The end result of the situational analysis is a map of the health sector that includes a number of elements:

- the demographic, social, political, economic, and institutional context of the health system;

- the health needs and the key factors affecting those health needs;

- the current services provided, their type, ownership, and level of activity and general performance;

- the resources available to the health sector both in terms of finance and real resources;

- identification of key stakeholders and actors related to this issue.

The situational analysis should also look at distributional issues particularly in terms of equity and should estimate the future situation in terms of health needs and resources.

Priority Setting

As indicated earlier, planning is associated with resource constraints. Not all health needs can be met and society must prioritize which interventions are essential for the achievement of desired objectives and which can either be postponed or skipped. Prioritization occurs at different levels and there is no technical standard as to the criteria for assessing and comparing health needs and who should set priorities. The guiding principles may include values (equity, gender, rights) as well as organizational motivation to improve performance such as efficiency. Wider participation of key actors (community, health professionals, policy makers) can improve responsiveness to the actual health needs rather than the needs perceived by decision makers. Economic appraisal techniques such as cost per disability-adjusted life year (a health measure introduced by the World Bank in the World Development Report 1993 and increasingly used in health planning afterward) may be used to set priorities based on a criterion of maximum health impact for given resources, but this can be criticized as being a narrow interpretation of goals and incorporating various contestable implicit values. For example, DALYs were recently criticized for taking into account only age, sex, disability period, and time with no consideration of the socioeconomic circumstances and thus focusing more on efficiency at the expense of equity (Anand and Hanson, 1998). Stakeholder analysis, Delphi techniques, multivariable decision-making matrices, and others are also important in prioritization and give greater emphasis to the political nature of planning.

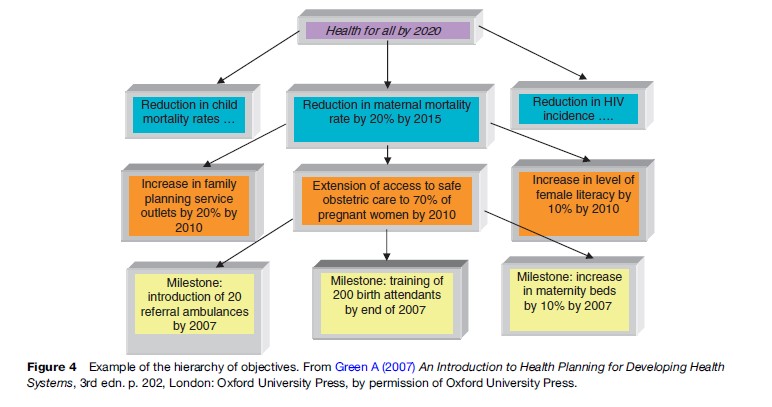

The end result of priority setting stage should be a set of objectives. As shown in Figure 4, these are normally across the hierarchy Goal/Aim – Objectives – Targets/ Milestones, which often corresponds to the LogFrame approach. The abbreviation SMART is often used as a checklist to appraise objectives against five criteria (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time bound).

Option Appraisal

At this stage, different alternatives for achieving the same objectives are assessed. The criteria for decisions should include underpinning values within the health system such as equity, but are often inappropriately driven only by performance-based judgments such as efficiency and technical and financial feasibility through techniques such as economic appraisal. It is helpful to deploy a holistic approach and include as many relevant criteria for assessing different options as possible to be able to form a comprehensive understanding of hidden issues such as cultural acceptability, sustainability of results in the long term, likely effects on health needs, and/or people’s expectations. One of the key criteria that should be considered is feasibility, including acceptability to key stakeholders. The use of stakeholder analysis at this stage is often important.

Techniques for option appraisal are similar to the ones used for priority setting and can be important in technology assessment including the development of Essential Service Packages. Examples of this can be found in the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and WHO CHOICE initiative.

Programing

This is the stage when the plan – the tangible output of the health planning process – is produced. The degree of detail within the plan depends on the level at which the document is produced. For example, a 10-year national health plan will have a relatively broad policy direction with fewer details on organizational requirements. In contrast, annual operational plans would outline the budget details, staff needs, supply system, and a detailed description of means of monitoring progress. The plan usually comprises sections, which mirror the stages of planning: background or situational analysis, rationale or priority setting, justification or option appraisal, work plan with identification of resources needed or programing, and monitoring and evaluation.

Log Frames have often been used as a tool to map out the health project in a concise format. Gantt charts present activities over a period of time. A number of programing tools are readily available, such as Microsoft Project. Costing and budgeting, integral components of programing, are often undertaken using spreadsheet templates designed for a particular program (see examples of WHO tools: the Cost It software tool and the mother-baby package costing spreadsheet).

The end product of this stage is a plan. It is, however, important to remember that the plan is not the end of the planning process but represents an intermediate output.

Implementation And Monitoring

Appropriate implementation is critical to the success of planning. Monitoring is the process by which progress is assessed. In many cases, implementation is the responsibility of implementing agencies, whereas the plan itself may be produced by planners alone. Where this is the case, difficulties may arise, including a lack of a comprehensive understanding of the objectives and means of achieving them and inadequate measures to monitor progress. Monitoring can often be based on existing support systems such as health management information systems (HMIS) or, less desirably, may require the establishment of a vertical system to collect, process, and analyze the data or even ad hoc surveys. Monitoring should be seen as a tool to support implementation and to help identify problems and adjust actions during implementation rather than as a ‘tick box’ exercise. The indicators and methods for monitoring should reflect the way of achieving the objectives and should lead to the next stage: evaluation.

Techniques used for programing such as Gantt charts are important for implementation and monitoring. The end product of this stage of planning is the record of implementation of a particular initiative and an assessment of progress during implementation.

Evaluation

Evaluation is the process of assessing whether the objectives set have been achieved and the causes for any deviation from this. It may be formative where it takes place during the implementation phase (allowing the opportunity to learn and adjust, and as such is closely related to monitoring) or summative. Summative evaluations are conducted at the end of a plan or project period. Evaluation often involves a combination of managers involved in the activity to gain access to in-depth understanding and facilitate learning, and outside experts to encourage objectivity. Information gained from an evaluation feeds into the next round of planning and the situational analysis.

The end result of this stage of the evaluation is a report on the implemented set of outputs, outcomes, and impact against its objectives.

Planning For Specific Inputs

The above has described the overarching approach to strategic and operational planning. Another aspect of the process relates to planning for specific inputs, which are briefly considered below.

Human Resource Planning

As health-care provision is extremely labor-intensive, it is essential that attention be paid to ensuring the right numbers of staff are trained, employed, and retained. Human resource planning is the subdiscipline that deals with this. Inadequate attention has been paid to human resource planning in recent years with the result that many health systems have a mismatch between their service plans and the staffing available. This has been further aggravated recently by international migration. It is essential that health systems analyze the needs for staff and develop appropriate policies acting on both the demand for and supply of staff that align with service plans.

Infrastructure Planning

Planning for new buildings and equipment has often been seen as a key part of planning (indeed often, inappropriately, given more priority than service planning). There are particular skills required in this aspect of planning in terms of ensuring that building designs meet user requirements and that the recurrent cost implications of new projects are fully recognized.

Financial Planning

We have already referred to the chain of financial allocations that occur and it is essential that planners align their plans with this process. Unfortunately, there is often an organizational mismatch between planning and financial planning, with different authorities for each. Financial planning is an integral element of health planning and is concerned with matching the resources to the existing plan. It is closely related to, but different from budgeting, in that it is concerned with broad matching of available funds with plans rather than specific budgets. Examples of financial planning at a wider public sector level include Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) and Public Investment Programme (PIP).

Capacity Required For Health Planning

Planning is not the sole responsibility of health planners. It should be seen as an integral element in the work of everyone who works within the health system, facilitated by specialists. However, the level and type of planning determines its characteristics, and this in turn affects the specialist capacity required.

Capacity for health planning does not only comprise a group of individuals with specific skills and experience. Besides technical skills in traditional disciplines such as epidemiology and economics, adequate planning capacity normally requires skills in other areas such as political analysis and advocacy. Planning also needs to draw on other processes within the health system such as the Health Management Information System.

Actors Involved In Health Planning

Planning occurs at all levels of the health system, with different actors involved in developing pieces of a common jigsaw.

Local-level planners usually develop operational details of the broad nationally determined policy or strategy. However, at a single level, there are inevitably different categories of actors involved in planning. For example, at the national level the health ministry should work closely with the education ministry on medical education issues; within the health system at the district level, the district hospital manager should work in close conjunction with the district primary health-care manager on operational issues, but their actions are also expected to be concerted with other local health-related issues such as transport or employment. Civil society, being often outside of the formal public sector entities, represents another group of actors that can be involved in the health planning.

Mechanisms For Engagement

A participatory approach involving key stakeholders is likely to improve the use of evidence, objectivity, and integration of planning efforts and to result in wider ownership of the planning product and prospects for implementation This suggests two issues related to stakeholder engagement in the planning process.

First, how can one ensure adequate participation of decision makers in the planning process? Planning processes need to be set up that fully involve key decision makers as part of their routine activity, which is seen as a key responsibility with appropriate incentives to reward time spent in considering the future as well as the immediate management issues.

Second, some groups of stakeholders such as civil society may not be easy to involve. Even those ostensibly involved in the planning process may not have the opportunity to express their views. There are various techniques for participation and empowerment of communities in the planning process (Rifkin and Pridmore, 2001). Direct involvement of representatives from these groups in the planning process via planning boards and workshops with appropriate training and support may help to empower such groups and to consider their views in the planning process.

Challenges In Planning

Earlier sections raised various challenges facing health planning, in particular:

- developing a balance between national and decentralized planning;

- responding to increasing international influences;

- achieving an appropriate balance between technical and political characteristics of health planning;

- forecasting – the balance between projections and blueprinting;

- scaling up positive experiences;

- harnessing new approaches to planning.

Development Of Balance Between National And Decentralized Planning

A balance is needed between national and local level planning, and the systems at each level need to be developed appropriately and consistent with each other. Many countries, such as former Soviet states, still deploy top down approaches as a means of communicating policy decisions and ensuring consistency of local planning initiatives with nationally determined agenda. However, top-down processes of command and control are increasingly seen as ineffective approaches, with health planning decisions often failing to recognize the local health needs or failing to be implemented. Deliberate strategies to develop local planning capacity and to shift national level roles to reflect the changing approach to planning.

Responding To Increasing International Influences

As health systems become more closely affected by the international context through the globalization of health, and new financial instruments such as Global Public Private Partnerships, national planners need to be able to respond to resultant pressures and complexity (Buse and Harmer, 2007). For example, the changing complexity of the aid architecture has led to approaches to donor support such as SWAps.

Managing The Tension Between Planning Techniques And The Politics Of Planning

Planning uses, as we have seen, various techniques. Planning involves making difficult choices about use of resources that will almost inevitably result in some groups becoming ‘losers’. As such, it is inevitably a political process and health planners need to be aware of this and develop ways of managing this tension. Many techniques (such as cost-effectiveness and the use of DALYs as outcome measures) appear to be technical and as such politically neutral, and yet implicit within them are value judgments. There is a need to achieve a balance between political, value-driven outputs and technically justified planning decisions.

Forecasting – Finding The Right Balance Between Modeling And Blueprinting

Modern technology is increasingly likely to allow the possibility of developing models for projections in areas such as epidemiological trends, human resources, and resource requirements for health care. However, such models need to be context-specific and driven by the local situation.

Scaling Up for MDGs

Global influences such as Millennium Development Goals, WHO’s 3-by-5 HIV/AIDS initiative, UNAIDS ‘road towards universal access’ to HIV prevention and AIDS treatment care and support by 2010 and others call for scaling up different interventions in many countries in order to achieve international targets. This puts significant pressure on health planning systems at different levels (subnational, national/country, region) to align health resources for the achievement of objectives both at the program level and at the wider health system level.

This poses an important and difficult planning question: What interventions will work on a larger scale as effectively as they were piloted? Many small-scale initiatives at the subnational level may not be appropriate to the whole country. On the other hand, issues such as social insurance may only be applicable at the larger scale.

Developing And Harnessing New Approaches To Health Planning

Health planning needs to evolve constantly and is developing for new techniques. There are significant potential opportunities becoming available through technology to collect and analyze data in ways that have the potential to enhance planning decisions. Geographical mapping and the linkage of local information to IT-based HMIS systems such as the application of geographical information systems for epidemiological surveillance (WHO, 1999) or establishment of a seasonal climate forecasting system for operational use by different sectors, including planning the health services (Thomson et al., 2000) provide exciting possibilities for understanding health needs and exploring options to respond to these.

Key Summary

Health planning is a complex process with at least three distinctive features (health being a labor-intensive sector, complex relationships between different actors, and the balance between clinical and public health perspectives). Planning is the product of values, techniques, and power relationships between different groups. Health planning is a continuous process and the production of a plan should not be seen as the end product of this process.

Approaches to planning will vary depending on the wider societal principles of decision making. There are various stages within the health planning cycle, with inevitable iterations. Presently, health planning faces a number of challenges and ultimately is an art of maneuvering within existing circumstances to achieve the desired objectives.

Bibliography:

- Anand S and Hanson K (1998) DALYs: efficiency versus equity. World Development 26(2): 307–310.

- Buse K, Mays N, and Walt G (2005) Making Health Policy. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

- Buse K and Harmer AM (2007) Seven habits of highly effective global public-private health partnerships: Practice and potential. Social Science and Medicine 64(2): 259–271.

- Green A (2007) An Introduction to Health Planning for Developing Health Systems, 3rd edn. London: Oxford University Press.

- Hyman H (1982) History. In: Hyman H (ed.) Health Planning: A Systematic Approach, pp. 1–24. Rockville MD: Aspen Systems Corporation.

- Reinke W (1988) Health Planning for Effective Management. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Rifkin S and Pridmore P (2001) Partners in Planning – Information, Participation and Empowerment. London: MacMillan Education.

- Rodwin V (1984) The Health Planning Predicament. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Soucat A, Vanerberghe UW, Diop F, Nguyen S, and Knippenberg R (2002) Marginal budgeting for bottlenecks: a new costing and resource allocation practice to buy health results: using health sector’s budget expansion to progress towards the Millennium Development Goals in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Taylor C and Reinke W (1988) The process, structure and functions of planning. In: Reinke W (ed.) Health Planning for Effective Management, pp. 5–20. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Thomson MC, Palmer T, Morse AP, Cresswell M, and Connor SJ (2000) Forecasting disease risk with seasonal climate predictions. The Lancet 355(9214): 1559–1560.

- Walley J, Wright J, and Hubley J (2004) Public Health an Action: Guide to Improving Health in Developing Countries. New York: Oxford University Press.

- WHO (1999) Geographic Information Systems (GIS): Mapping for epidemiological surveillance. Weekly Epidemiological Record 74(34): 281–285.

- Easterly W (2006) The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good. London: Penguin Press.

- Green A and Collins C (2006) Management and planning for public health. In: Merson MH, Black RE, and Mills AJ (eds.) International Public Health, 2nd edn., pp. 553–599. Jones and Bartlett.