View sample young people and violence research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The Magnitude Of Youth Violence

Youth violence is a devastating public health problem worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, over 540 adolescents and young adults die every day from interpersonal violence. Annually, anywhere from 3.5 to 7.5 million young people experience injuries from violence requiring hospital treatment. Indeed, the health consequences of violence are severe, including death, permanent physical disabilities, high costs of medical care and rehabilitation, and immeasurable grief and suffering. The availability of guns heightens the lethality of youth violence. In fact, the problem of youth violence in the United States and in many other countries is of major health and social significance because it is largely a problem of gun violence.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The public health approach to prevention comprises the following steps: (1) Defining the problem, (2) identifying risk and protective factors associated with the problem, (3) developing interventions to address these factors, (4) implementing and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions through initial pilot work and larger-scale studies, and (5) disseminating successful models. This approach has been successfully applied to many causes of morbidity and mortality, including smallpox, lung cancer, and motor vehicle crashes. As described below, these steps can also be applied to youth violence and are, in fact, critical for its prevention (Mercy et al. 1993).

Worldwide, violence is one of the most serious threats to the health of adolescents. In 2000, the World Health Organization World Report on Violence and Health estimated that 199 000 youth between the ages of 10 and 29 (9.2 per 100 000) were murdered globally. Around the world, there are stark differences in youth homicide rates linked to clear, identifiable socioeconomic and political factors. Where there is political and social instability, such as in Colombia in the 1990s and in Russia, youth homicide rates are high (84.4 per 100 000 in Colombia in 1995, 18.0 per 100 000 in Russia in 1998) (Krug et al., 2000). In South Africa in 2004, 51.7% of injury deaths in 15to 24-year-olds were caused by violence. Conversely, in the politically stable countries of Western Europe, homicide rates were much lower (<2 per 100 000 estimated in 2000) (Krug et al., 2000). In the United States, the National Adolescent Health Information Center reported that an average of 14.5 youth aged 10–24 were murdered each day in 2004 (8.4 per 100 000).

Around the world, homicide rates are substantially higher for males than for females. The magnitude of this disparity varies greatly, however, and is primarily determined by the male homicide rate, as female homicide rates are comparatively consistent globally. For instance, in 1998, the male homicide rate for youth 10–29 years old in France was 0.7 per 100 000 and the rate for females was 0.4 per 100 000 (Krug et al., 2000). Thus, the ratio of male to female homicides in France was 1.9. In Mexico, on the other hand, the homicide rate for males in 1997 was drastically higher than that of France at 27.8 per 100 000, while the homicide rate for females was 2.8 per 100 000 (Krug et al., 2000). Consequently, the male to female homicide ratio was a much higher 9.8.

Globally, firearms are the most common method of perpetration in youth homicides. In 2004, 45% of intentional injury deaths among 15to 24-year-olds in South Africa were from gunshots. In the United States, 82% of youth aged 10–24 murdered in 2004 were killed with firearms (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2007). The sharp rise in youth homicides from 1983 to 1993 was linked to an increase in firearm usage in the commission of crimes. Similarly, the drop in homicide rates from 1993 to 1999 can be traced largely to a decline in the use of firearms (Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). The 2005, Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBS) found that in the United States, 9.9% of males and 0.9% of females reported carrying a gun at least once in the past 30 days, while in 1991, 13.7% of males and 1.8% of females reported the same.

The World Report on Violence and Health reported a global increase in youth homicides between 1985 and 1994. During this time, the increases in homicides were greatest among males and in developing countries. While other methods of attack remained steady or decreased, use of firearms as the method of attack in homicides increased during this period of increasing homicides. In the United States, there was a peak in arrests of young people for violent crimes from 1983 to 1993. However, in the 1990s, youth arrests began to decline and, by 1999, rates were nearly back to 1983 levels. While arrest rates for homicides declined, however, self-reports of violent behavior remained level throughout the 1990s (Department of Health and Human Services, 2001).

Nonfatal violence is far more common than homicide. For example, while the homicide rate in the United States in 2004 for 10to 24-year-olds was 9.6 per 100 000, the assault rate was 3079 per 100 000 (National Adolescent Health Information Center, 2007). Physical fighting is prevalent among school-age children around the world. Studies in several countries in the late 1990s found that approximately one-third of adolescents reported involvement in fighting (Krug et al., 2000). Bullying behavior is also common, but varies considerably between countries. In a cross-national survey conducted during the 1997–98 school year in classrooms where the average ages were 11.5, 13.5, and 15.5 years, 9% of youth in Sweden reported more than two incidents in the past school term where they were either bullied, victimized by a bully, or both, while in Lithuania the prevalence of these bullying behaviors was 54% (Nansel et al., 2004). Of U.S. youth in the 2005 YRBS, 9.2% reported being hit, slapped, or physically hurt on purpose by their boyfriend or girlfriend.

The violence of war and armed conflict reaches into many childhoods around the world. The United Nations World Youth Report 2003 (2004) estimated that, in the previous decade, two million young people were killed by armed conflict and another five million were disabled. Between 1989 and 2000, there were 111 armed conflicts in the world. Most of the warfare occurred in the developing world. In 2003, an estimated 300 000 youth soldiers aged 10–24 fought in active armed conflicts.

The considerable variations in youth homicide rates and nonfatal violence between countries and regions of the world support the conclusion that violence is preventable. If violence were inevitable, rates from country to country would be expected to be very similar. In fact, there are many strategies that have been shown to be effective in reducing youth violence.

Risk And Protective Factors For Youth Violence

The Resilience Paradigm

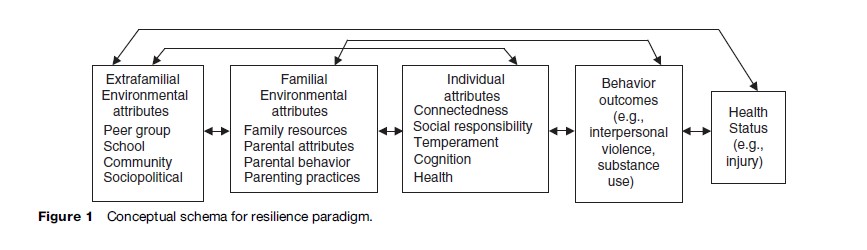

The paradigm of resilience proposes that adolescents’ vulnerability to health-jeopardizing outcomes, such as violence, is affected by both the number and nature of stressors in their lives, as well as the presence of factors that buffer and protect against adverse outcomes. Based on the work of Chase-Landsdale and colleagues, and modified by Resnick in 2000 (Resnick, 2000), the paradigm incorporates multiple processes in characterizing the dynamics that affect the well-being and specific behaviors of young people. Depicted in Figure 1, behavioral outcomes and health status, both positive and negative, are described as emanating from the interplay of factors enacted within the significant social systems in young peoples’ lives, including their families, schools, peer groups, and neighborhoods.

Figure 1 Conceptual schema for resilience paradigm

Research on health-compromising behaviors has traditionally focused on the so-called problemness of young people. The resilience paradigm, in contrast, seeks to identify protective, nurturing factors in the lives of those who would otherwise be expected to have poor outcomes. Rather than focusing solely on pathology, this framework seeks to understand successes, strengths, and solutions embedded in young people’s lives. Thus, a resilience based approach to violence prevention might focus on issues related to family functioning, which is associated with violence involvement among youth, with the goal of improving parent–child connectedness in a prosocial context and, in doing so, reduce violent behaviors.

Individual Risk And Protective Factors

The strongest predictor of involvement in violence is a history of previous violent behavior. Physical fighting and bullying behaviors often precede more serious violent behaviors, including weapon carrying, fight-related injury, and homicide among youth. In the United States, similarities noted between the demographic patterns of physical fighting and homicide suggest that fighting is part of a spectrum of violent behavior that includes homicide. In addition to aggressive behaviors and violent acts, early involvement in nonviolent offenses, such as burglary, is a powerful risk factor for adolescent violence (Department of Health and Human Services, 2001).

Notably, the factors that predict violence perpetration parallel the risk factors for sustaining violence-related injury. In fact, studies have documented that victims of violence are disproportionately the perpetrators of violence (Rivara et al., 1995). Violence-related injury has been described as analogous to a chronic recurrent disease, with rates of recidivism as high as 44% and 5-year mortality rates as high as 20% (Sims et al., 1989).

Both theory and research suggest that multiple problem behaviors cluster among adolescents. A generation ago, Jessor’s Problem Behavior Theory described health-risk behaviors, such as violence, alcohol and drug use, suicidal behaviors, and sexual activity, as a syndrome among adolescents, most likely reflecting common underlying etiological factors. The association between violence and alcohol and drug use has been widely documented. Both perpetrators and victims of violence have frequently used alcohol and/or other drugs (American Psychological Association, 1993; Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Although suicidal behavior has been described as a quietly disturbed behavior and interpersonal violence as an acting-out behavior, self-directed and interpersonal violence are interrelated. For example, factors that are strong predictors for attempting suicide, such as a previous suicide attempt, suicide, or suicide attempt by a family member or friend, depression, and violence exposure, are also risk factors for interpersonal violence involvement among young people (Resnick et al., 1997, 2004; Borowsky and Ireland, 2004).

Hyperactivity, impulsiveness, and attention problems in childhood increase the risk for subsequent violence involvement among youth. Longitudinal studies in Copenhagen, Denmark; Dunedin, New Zealand; Orebro, Sweden; Cambridge, England; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in the United States have found associations between these childhood personality traits and both self-reported violence and convictions for violence in adolescence and early adulthood. Low intelligence, learning problems, and school failure are also significant risks for youth violence (Krug et al., 2000).

Individual-level protective factors for violence include emotional health, school achievement, and a personal sense of religiosity or spirituality (Resnick et al., 2004). Other key protective factors found in resilient young people are positive social skills and general self-efficacy.

Family Risk And Protective Factors

At the family-level, exposure to family violence impacts youth violence. Children who are abused or witness violence in their home are more likely to become perpetrators or victims of violence themselves, both in their intimate relationships as well as outside the home. Other family-level risk factors for violence are parental substance abuse, overcrowding, economic deprivation, high levels of parenting stress and family conflict, and ineffective parenting. Ineffective parenting includes overly harsh and inconsistent discipline, inadequate supervision of children, and lack of affection (American Psychological Association, 1993; Krug et al., 2000).

Family caring and connectedness has repeatedly been found to be a powerful protective factor against violence and other health-risk behaviors among youth (Resnick et al., 1997). Family connectedness includes closeness to and perceived caring by a parent, satisfaction with one’s relationship to parents, and feeling loved and wanted by family members. In addition to supportive parent–child relationships, positive and consistent discipline, parental monitoring and supervision, and good communication in families are critical family protective factors in promoting resilience to violence involvement. Across cultures and economic circumstances, research shows that children and teens raised in homes characterized by authoritative parenting show strong advantages in psychosocial development, mental health, social competence, academic performance, and avoidance of problem behaviors compared to their peers raised in any of the other three styles, referred to as permissive or indulgent, authoritarian or autocratic, and unengaged (or neglectful at the extreme) (Barber et al., 1992). The authoritative parent is warm and involved but is firm and consistent in establishing and enforcing limits, guidelines, and appropriate expectations.

Extrafamilial Risk And Protective Factors

Youth who socialize with peers who are engaging in violent or criminal behavior, whether by choice or by default, are more likely to engage in violent behavior themselves. Involvement in antisocial groups such as gangs promotes violence among youth. Exposure to neighborhood and community violence is also a risk factor for participation in violence (Herrenkohl et al., 2000; Krug et al., 2000).

This dynamic of differential association highlights the salient role of peer behaviors and perceived peer norms in the modeling and diffusion of violent behavior among adolescents. However, in regard to the specific manifestation of violence in the form of firearm use, international data support the link between availability and access to guns and gun violence. Studies comparing rates of violence in cities with different gun control policies have identified gun availability as a critical factor associated with firearm-related violence. For example, the relative risk of assault and homicide by firearm was significantly higher in Seattle, Washington when compared to Vancouver, British Columbia, where handguns are less available due to more stringent gun control (Sloan et al., 1988). Furthermore, studies in the United States have identified gun ownership as an independent risk factor for homicide in the home, usually by a family member or intimate acquaintance (Duke et al., 2005).

The availability of guns makes youth violence more lethal. Injury outcomes are affected by both the frequency and severity of violent incidents. While factors such as alcohol and drug use and economic inequality affect the frequency of violent events, guns increase the severity of violence, since guns are more likely to kill than any other weapon used in an assault. If firearm injuries could be prevented, violent events would still occur, but the severity of the injuries would be greatly reduced.

Poverty and its contextual life circumstances are strongly linked to violence. Globally, there is a strong link between income inequality and violence, with studies in both industrialized and developing countries demonstrating a robust, significant association between income inequality and homicide rates (Krug et al., 2000). Regardless of race or ethnicity, at the population level, violence is most prevalent among the poor. Beyond neighborhood effects such as heightened exposure to violence, potential mechanisms for how poverty influences children’s behavior includes effects at the family level, such as less parental supervision, more parental distress, parents’ lower levels of emotional responsiveness to their children, more frequent use of physical punishment, and lower-quality home environments among children in low-income families.

The culture and history of violence in a society have important effects on rates of violence as well. Societal norms and values may support violent behavior by endorsing and teaching violence as an acceptable way to resolve conflicts. Cultural influences include folk heroes and media images that glorify interpersonal violence, violent team sports, and guns and war toys that are marketed to young children (American Psychological Association, 1993).

Estimates indicate that the average U.S. child or teenager views over 10 000 acts of violence per year on television (Krug et al., 2000; American Academy of Pediatrics 2001). Access to media in other parts of the world is variable, but overall is extensive and growing. Hundreds of studies have led to the firm conclusion that viewing violence increases real-life violence (Centerwall, 1992; Paik and Comstock, 1994; Krug et al., 2000). Research shows that viewing violence on television is associated with short-term increases in aggressive behavior. It can also lead to emotional desensitization toward violence and an increased fear of becoming a victim of violence. Furthermore, longitudinal studies conducted in the United States over 10–15 years demonstrate long-lasting effects of childhood television viewing on aggression in adolescence and early adulthood (Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Shorter longitudinal studies in other countries have shown inconsistent results (Krug et al., 2000).

A powerful protective factor against violence is school connectedness. Components of school connectedness include perceived closeness to people at school, perceived teacher caring, feeling part of your school, feeling happy at school, believing that teachers treat students fairly, and feeling safe at school. School connectedness, like family connectedness, has been found to be protective against almost every health-risk behavior among youth, including violence (Resnick et al., 1997). Other extrafamilial environmental protective factors are perceived connectedness with adults outside of the family, who recognize, value and reward prosocial, not antisocial behavior, and perceived neighborhood safety.

Multiple Opportunities For Prevention

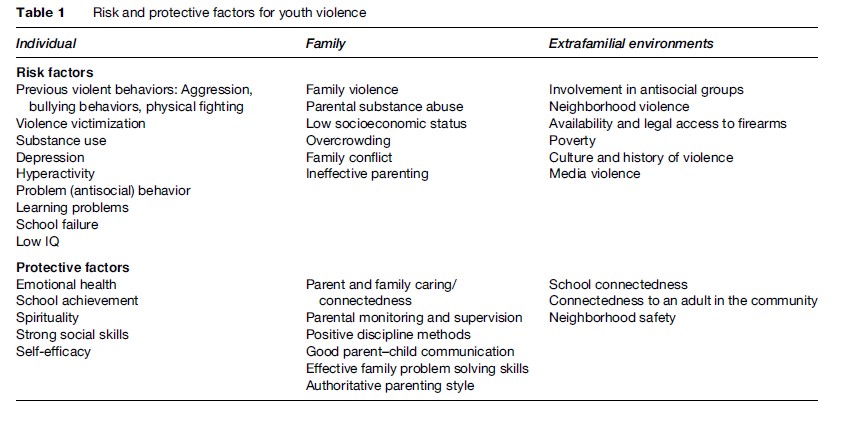

Because there are multiple factors that predispose to and buffer against violence involvement and injury (summarized in Table 1), there are also multiple prevention strategies to choose from. Violent injuries result from a chain of circumstances and, consequently, present multiple opportunities for prevention along that chain. A combination of strategies used together is likely to be most successful in preventing youth violence.

Table 1 Risk and protective factors for youth violence

Interventions To Prevent Youth Violence

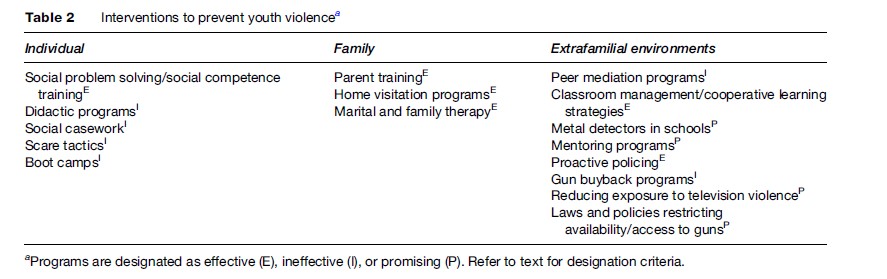

While most of the hundreds of youth violence prevention programs implemented in schools and communities throughout the world have not been rigorously evaluated, there are sufficient evaluations of acceptable methodological rigor from which to draw conclusions about some approaches to youth violence prevention that work, that do not work, and that are promising (Table 2). In order to be designated as an effective strategy, programs must have multiple controlled evaluation studies demonstrating their positive effects in reducing violence. Ineffective programs have had multiple evaluation studies demonstrating their lack of effect or negative effects on violence. Promising programs are those that have demonstrated success, but lack multiple evaluation studies. Several reviews inform this section (Sherman et al., 1998; Tolan and Guerra, 1998; Krug et al., 2000; Department of Health and Human Services, 2001; Thornton et al., 2002).

Table 2 Interventions to prevent youth violence

Individual-Level Interventions

Many interventions focus on the individual and attempt to modify individual risk factors for youth violence. Individual-level interventions are prevalent because much of the discussion regarding youth violence has been grounded in the belief that the problem results primarily from the dysfunctional behavior of individuals. Interventions at this level are also popular because they are easier to implement and their effects are easier to measure than other types of interventions.

Programs focused on increasing social problem-solving and competency skills are an effective individual-level intervention. These programs train participants to follow a sequence of discrete steps when solving common social problems. They also teach and rehearse perspective-taking skills and moral reasoning. These programs have been found to improve social problem-solving skills and social competence and reduce conduct problems and aggressive behavior among participants. An example of this type of program implemented in the school setting is Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS), which consists of 20to 30-min sessions taught three to five times a week throughout the elementary school years. PATHS has successfully been used with general education and special education students throughout the United States and in England, Wales, Scotland, the Netherlands, and Australia.

Several individual-level interventions are demonstrably ineffective. Didactic programs that focus on dissemination of information in a lecture format are ineffective. A well-known example of this is Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE). DARE is the most widely implemented youth drug prevention program in the United States. The curriculum is taught by police officers over 17 weekly lessons, primarily to 5th and 6th graders. Numerous well-designed evaluations and meta-analyses have consistently shown little or no deterrent effects of the program on substance use or delinquent behavior. Nonetheless, DARE receives substantial support from parents, teachers, police, and government funding agencies. Changes are being made in an attempt to improve the program’s effectiveness, such as adding social skills training sessions to the core curriculum.

Social casework, which is used extensively in the juvenile justice system, is also an ineffective violence prevention strategy. This approach is a mainstay of juvenile justice and social services, but research indicates that it is not effective in preventing or reducing serious antisocial and violent behavior, even when services are comprehensive and carefully delivered. Evaluated numerous times, intensive casework has failed to show positive effects and in some cases, negative effects have been shown among youth receiving the casework services as compared to control groups.

Scare tactics, such as Scared Straight programs, where youth with minor offenses have brief encounters with maximum security prison inmates who describe the brutality of prison life, do not work and, in some studies, have been associated with increased rates of crime and rearrest. Boot camps for delinquent youths are modeled after military basic training. The primary focus is on discipline. Compared to traditional forms of incarceration or parole, boot camps have been found to produce either no significant effects or an increase in repeat offending.

Family-Level Interventions

Family-level interventions are among the most promising interventions known to date. Interventions of this type have repeatedly shown efficacy and effectiveness for reducing behavioral problems, violent and delinquent behavior, and substance use among youth. Successful programs promote effective family functioning, including developing strong family emotional bonding, providing good supervision of children, clearly communicating and enforcing behavioral norms, and using critical thinking skills to solve problems. Effective family-level interventions include parent training programs, home visitation programs, and family therapy.

The evidence base documenting the effectiveness of parent training programs in improving parenting skills and family cohesion, and reducing aggressive behavior and substance use among children and adolescents is extensive (Kumpfer and Alvarado, 1998). The efficacy of parent training has been observed in numerous randomized controlled trials in high-risk populations including children and adolescents with serious behavioral disorders and delinquency and those with detectable problems who do not yet meet criteria for a behavioral disorder. Parent training programs have been found to produce significant improvements in parenting skills and child behavior problems among families from diverse economic backgrounds. Many programs are video-based, showing effective and ineffective parenting skills in videotaped vignettes. These programs have significantly improved parenting skills and reduced child behavior problems even when self-administered. Moreover, the children’s behavior continues to improve over the long term. The addition of consultation sessions with a therapist to the videotape program has been shown to result in even better outcomes. Evidence from evaluation studies in Australia and the United States further suggests that weekly telephone sessions are an effective way to deliver parenting education to reduce aggressive behavior and violence in children and youth (Borowsky et al., 2004). Telephone-based delivery can facilitate access to parents throughout a wide geographic area and holds promise as a strategy for widespread dissemination of effective interventions.

Examples of successful parent training programs include the Triple-P-Positive Parenting Program in Australia, implemented in China, Germany, New Zealand, Singapore, and the United Kingdom, and the Incredible Years Parenting Series used in the United States. Of early interventions to prevent serious crimes, Greenwood and colleagues (1998) found that parent training was the most cost-effective, and was much more cost-effective than incarceration.

Home visitation programs involve weekly to monthly visits by nurses during pregnancy, continuing for the first 2 years of a child’s life. The nurses provide parenting information, emotional support, counseling, and linkage to social services. Long-term follow-up indicates that children who are visited have lower rates of offending as teenagers, less antisocial behavior, and less substance use than those not receiving home visitation (Olds et al., 1998). The positive impact of this approach illustrates that an intervention during the first 2 years of a child’s life can have an enduring effect on development. Home visitation programs have been implemented throughout the world, including Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Estonia, Israel, South Africa, Thailand, and the United States.

Marriage and family therapy approaches have also demonstrated positive impacts on antisocial behavior in children. Family therapy seeks to change patterns of family interaction and communication through a therapist working with family members together in a group. Three successful family therapy programs used in the United States with youth already involved in violence and/or chronically offending and in the juvenile justice system are Functional Family Therapy, Multi-systemic Therapy, and Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care. Program outcomes include long-term reductions in arrest rates among juvenile offenders.

Extrafamilial Environmental-Level Interventions

This broad domain includes interventions directed toward peers, schools, neighborhoods and communities, and society as a whole.

In peer mediation programs, students agree to have their disputes mediated by a peer who has been trained to help both parties analyze the problem and reach a nonviolent resolution. The process is designed to reach consensus, maintain confidentiality, and avoid blame. Evaluations have found no evidence of a positive effect and, in some cases with high school students, harmful effects.

Classroom management interventions include establishing expectations for classroom behavior, using rewards and punishments to enforce classroom rules, and using instructor aides and parent volunteers to assist in the classroom. Cooperative learning strategies include small group learning to reinforce and practice what is learned. The Seattle Social Development Project is a program used in both elementary and middle school that includes these components and has been found to have a strongly positive impact both on academic outcomes as well as delinquency and drug use in follow-up studies over two decades. The Olweus Bullying Prevention Program includes classroom management strategies to establish and enforce class rules against bullying, in conjunction with a school-wide component and an individual component that includes working with students identified as bullies and victims, and their parents. Initially implemented in elementary and junior high schools in Bergen, Norway, the program has been replicated in England, Germany, and the United States. The intervention has been associated with significant reductions in bullying and antisocial behavior.

Another school-level violence intervention is changing the physical environment of the school so that it is more physically secure. Using metal detectors and other security systems has been shown to significantly reduce weapon-carrying in schools, but they have not been found to reduce threats and fighting either within or outside of school. With fewer guns in school, however, there is the potential to reduce the lethality of conflicts within the school building.

Mentoring programs recruit an adult to meet with a young person on a regular basis, in an effort to duplicate the kind of relationship with a caring adult that is so protective for youth against an array of health-jeopardizing outcomes. Challenges encountered by mentoring programs include making an appropriate match between the adult and the child, maintaining a regular schedule of contact, and defining expectations of the mentoring relationship. The majority of mentoring programs have not been evaluated as antiviolence strategies. A large-scale evaluation of the Big Brother/Big Sister program in 1992 and 1993 in eight cities in the United States found that over an 18-month period, mentored youth were less likely than controls who were placed on a waiting list to initiate alcohol and drug use or to hit someone. Moreover, they skipped half as many school days as control youth. This Big Brother/Big Sister program emphasizes frequent contact between the adult and the atrisk youth. They screen volunteers and conduct an orientation and training. Support is also offered by professional case workers.

In contrast to reactive policing, e.g., responding to 911 calls, proactive policing, as the name suggests, takes a more proactive approach to crime control. One example of this is targeting high-risk venues to suppress hot spots. The Boston Miracle, a dramatic reduction in youth homicides and all gang-related gun violence in Boston in the 1990s, was at least in part attributed to policing interventions. Tactics included systematic tracing of illegal firearms, interventions focused on gangs, and aggressive enforcement of terms of parole. Consistent with public health practices in other areas of prevention and behavior change, this intervention was multisectoral, involving the collaboration of law enforcement with education, health and social services, and the involvement of influential community opinion leaders.

Gun buyback programs are expensive and have consistently shown no effect on gun violence. There is some evidence that most of the guns turned in are dysfunctional, and that most people turning in guns have other guns at home.

Public policy is perhaps the most fertile but underutilized area for youth violence prevention. Because policy is broad-based, its potential impact is far greater than other programing. Additionally, public policy and other societal level interventions are powerful because they have the potential to work automatically to protect children from violent injuries. Many of the interventions that operate at the individual and other environmental levels are active strategies. These interventions require the action of a child, a parent, or a teacher on every occasion to work. Strategies such as using social problem-solving skills in a conflict situation, practicing positive parenting skills to prevent misbehavior, or recognizing warning signs in a troubled student and obtaining appropriate help can be very effective when implemented. But active strategies, in general, are not as effective as passive strategies, because they depend on repeated actions to work, thereby affording many opportunities for human error. Passive strategies are safety nets that work automatically to help prevent injury. Not having a handgun in the home is one example of a strategy that works automatically to protect against injury, by limiting immediate access to means for a highly lethal form of violence. There are two types of societal-level interventions that have been empirically evaluated to some extent and are directly related to adolescent violence: Decreasing exposure to media violence and decreasing access to firearms, especially handguns.

The studies that have been conducted to date on media violence suggest that any significant effect on youth violence is likely to require decreasing media violence content and the exposure of children and adolescents to such violence, as well as encouraging parents to monitor and critically discuss with children and adolescents the violence seen on television and through other media. A randomized controlled study conducted of an intervention to reduce television, video, and video game use that included thirdand fourth-grade students in two elementary schools in California found that the intervention significantly reduced aggressive behavior in these children (Robinson et al., 2001). Other studies include natural experiments. A remote town in Canada was unable to receive television for several years. When television again became available to residents, aggressive behavior among children increased sharply. In South Africa, many communities were denied access to television for political reasons. After reforms, television was introduced and the murder rate greatly increased. The results of these natural experiments should be interpreted with caution, however, as social and political factors may confound the relationship between television and the observed violence.

Several studies provide evidence that restricting access to handguns may reduce community-wide homicide rates. A study evaluating a regulation in Washington, DC, restricting the purchase, transfer, and sale of handguns, with stiff penalties for violation of the ordinance, demonstrated an immediate and significant reduction in firearm homicides following adoption of the regulation. Nonfirearm homicides did not decrease significantly in the same time period, and firearm homicides in nearby comparison areas also did not drop (Loftin et al., 1991). During the 1990s, gun carrying was banned in areas of Colombia during certain weekends known to have higher homicide rates, such as weekends after paydays. Homicides were found to be lower when the ban on carrying guns was in effect (Villaveces et al., 2000).

A systematic review of the effects of federal and state laws restricting access to firearms on violence in the United States found insufficient evidence to determine effectiveness due to a paucity of studies. Design modifications to reduce the lethality of firearms, particularly handguns, is a prevention strategy with potential for reducing injury from firearm violence that requires development and evaluation (Duke et al., 2005).

Principles Of Effective Interventions

Dusenbury and colleagues (1997) compiled a list of key components of promising violence-prevention programs, based on a review of the literature and interviews with violence-prevention experts. First, effective programs include a comprehensive, multifaceted approach that promotes connectedness to family, school, and community.

Effective programs are developmentally appropriate, begin in the early grades, and continue through adolescence. They promote competence in the areas of self-control, decision making, problem solving, listening, and communication skills. Promising programs involve interactive techniques and rehearsal, as children and youth often learn best by doing, and learning is reinforced through a variety of activities, such as group work, discussions, and role plays. Promoting cultural identity, providing staff training, and promoting a positive climate are all important elements of effective interventions. Lastly, effective school-based violence-prevention programs include activities that foster a climate that does not tolerate violence, aggression, or bullying. The goal is to create a culture where peace is the norm.

Challenges To Disseminating Successful Models

Although there are many effective youth violence prevention strategies, the effectiveness of most existing programs worldwide is unknown because the strategies used are untested. At the same time, the presence of persuasive evidence is not sufficient to assure adoption of demonstrably effective interventions. Even the most effective strategies for preventing violence and other behavioral problems among youth, such as parent training interventions, have not been widely implemented. Challenges for community adoption and implementation include locating resources to initiate programs and successfully replicating interventions implemented in another setting. When the resources and political will are present to permit implementation of successful interventions, the complex issues of adaptation to fit community norms and needs can stymie progress, or result in modification or elimination of intervention characteristics most critical for success. Beyond this, when effective strategies are enacted, including successful adaptation to assure good fit with community characteristics, the challenges of sustainability are often insurmountable. Maintaining effective interventions over time usually requires creative multisectoral mobilization and advocacy to both build and sustain the agenda for ongoing youth violence prevention. And to assure a continued goodness of fit between an intervention and a changing youth population in evolving social contexts, periodic evaluation and feedback is a necessary (and often neglected) component.

Conclusion

The short and long-term consequences of violence at the individual, familial, and community level continue to make youth violence prevention a compelling public health concern around the world. From the perspective of public health research, programs, policy, and practice, there are well-established, well-understood factors that dramatically increase the likelihood of violence involvement, just as there are known, effective approaches to reducing and preventing young people from witnessing, experiencing, and perpetrating violence. The movement to adopting and sustaining strategies that both reduce risk and enhance protective factors, grounded in the evidence of what works, requires a public health knowledge base, a deep understanding of community context, and the requisite skills in advocacy and agenda building that can effectively promote the use of effective strategies. The growing evidence base demonstrates that there is an ever-widening array of interventions, at the individual, family, and community level, that will decrease the reach, the severity, and the likelihood of violence involvement among all young people.

References:

- American Academy of Pediatrics (2001) Media violence. Pediatrics 108: 1222–1226.

- American Psychological Association Commission on Violence and Youth (1993) Violence and Youth: Psychology’s Response Vol. 1. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Barber B (1992) Family, personality, and adolescent problem behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family 54: 69–79.

- Borowsky I and Ireland M (2004) Predictors of future fight-related injury among adolescents. Pediatrics 113: 530–536.

- Borowsky IW, Mozayeny S, Stuenkel K, and Irleand M (2004) Effects of a primary care-based intervention on violent behavior and injury in children. Pediatrics 114: e392–e399.

- Centerwall BS (1992) Television and violence: The scale of the problem and where to go from here. Journal of the American Medical Association 267: 3059–3063.

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Wakschlag LS, and Brooks-Gunn J (1995) A psychological perspective on the development of caring in children and youth: The role of the family. Journal of Adolescence 18: 515–556.

- Department of Health Human Services (2001) Youth Violence: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Mental Health Services; and National Institutes of Health National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44294/.

- Duke N, Resnick MD, and Borowsky IW (2005) Adolescent firearm violence. Position paper of the Society for Adoelcent Medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health 37: 171–174.

- Dusenbury L, Falco M, Lake A, Brannigan R, and Bosworth K (1997) Nine critical elements of promising violence prevention programs. Journal of School Health 67: 409–414.

- Greenwood PW, Rydell CP, and Model KE (1998) Diverting Children from a Life of Crime: Measuring Costs and Benefits. (revised edn.). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Herrenkohl TI, Maguin E, Hill KG, et al. (2000) Developmental risk factors for youth violence. Journal of Adolescent Health 26: 176–186.

- Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, and Lozano R (2000) World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/full_en.pdf.

- Kumpfer KL and Alvarado R (1998) Effective Family Strengthening Interventions. OJJDP Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

- Loftin C, McDowall D, Wiersema B, and Cotey TJ (1991) Effects of restrictive licensing of handguns on homicide and suicide in the District of Columbia. New England Journal of Medicine 325: 1615–1620.

- Mercy JA, Rosenberg ML, Powell KE, Broome CV, and Roper WL (1993) Public health policy for preventing violence. Health Affairs 12: 7–29.

- Nansel TR, Craig W, Overpeck MD, Saluja G, and Ruan WJ (2004) Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviors and psychosocial adjustment. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 158: 730–736.

- National Adolescent Health Information Center (2007) Fact Sheet on Violence: Adolescents and Young Adults. San Francisco, CA: University of California San Francisco. https://nahic.ucsf.edu/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/Violence2007.pdf.

- Olds DL, Henderson CR, Cole R, et al. (1998) Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children’s criminal and antisocial behavior: 15-Year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 280: 1238–1244.

- Paik H and Comstock G (1994) The effects of television violence on antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis. Communication Research 21: 516–546.

- Resnick MD (2000) Protective factors, resiliency and healthy youth development. Adolescent Medicine: State of the Art Reviews 11: 157–164.

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. (1997) Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association 278: 823–832.

- Resnick MD, Ireland M, and Borowsky IW (2004) Youth violence perpetration: What protects? What predicts? Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of Adolescent Health 35: 424.e1–424.e10.

- Rivara FP, Shepherd JP, Farrington DP, Richmond PW, and Cannon P (1995) P Victim as offender in youth violence. Annals of Emergency Medicine 26: 609–614.

- Robinson TN, Wilde ML, Navracruz LC, Haydel KF, and Varady A (2001) Effect of reducing children’s television and video game use on aggressive behavior: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 155: 17–23.

- Sherman LW, Gottfredson DC, MacKenzie DL, et al. (1998) Preventing Crime: What Works, what Doesn’t, What’s Promising. Washington DC: Research in Brief National Institute of Justice. http://www.chs.ubc.ca/archives/files/Preventing%20Crime%20what%20works,%20what%20doesn’t,%20what’s%20promising.pdf.

- Sims DW, Bivins BA, Obeid FN, et al. (1989) Urban trauma: A chronic recurrent disease. Journal of Trauma 29: 940–947.

- Sloan JH, Kellermann AL, Reay DT, et al. (1988) Handgun regulations, crime, assaults, and homicide: A tale of two cities. New England Journal of Medicine 319: 1256–1262.

- Thornton TN, Craft CA, Dahlberg LL, Lynch BS, and Baer K (2002) Best Practices of Youth Violence Prevention: A Sourcebook for Community Action. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

- Tolan P and Guerra N (1998) What Works in Reducing Adolescent Violence: An Empirical Review of the Field. Boulder, CO: Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence.

- United Nations (2004) World Youth Report 2003: The Global Situation of Young People. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat. https://www.un.org/development/desa/youth/world-youth-report/world-youth-report-2003.html.

- Villaveces A, Cummings P, Espitia VE, et al. (2000) Effect of a ban on carrying firearms on homicide rates in two Colombian cities. Journal of the American Medical Association 283: 1205–1209.

- Behrman RE (ed.) (2002) The Future of Children: Children, Youth, and Gun Violence, Vol. 12. Los Altos, CA: David and Lucile Packard Foundation. https://www.jstor.org/stable/i273913.

- Jessor R (1991) Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. In: Rogers DE and Ginzburg E (eds.) Adolescents at Risk: Medical and Social Perspectives, pp. 19–34. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Moffitt TE, and Caspi A (1998) The development of male offending: Key findings from the first decade of the Pittsburgh youth study. Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention 7: 141–171.

- Resnick MD (2005) Healthy youth development: Getting our priorities right. Medical Journal of Australia 183(8): 398–400.

- https://cspv.colorado.edu/ – Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence.

- https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/en/ – World Health Organization: Violence and Injury Prevention.