Sample Public Health As A Social Science Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Public health can be defined as:

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

the combination of science, skills and beliefs that are directed to the maintenance and improvement of the health of all people through collective or social actions. The programs, services, and institutions involved emphasize the prevention of disease and the health needs of the population as a whole. Public health activities change with changing technology and values, but the goals remain the same: to reduce the amount of disease, premature death and disability in the population (Last 1995, p. 134).

Health was defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) almost 40 years ago as a state of complete mental, physical, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity (WHO 1964). From this definition, health is clearly more than just a physical state and is inextricably linked to personal well-being and potential, and incorporates other dimensions of human experience, such as quality of life, psychological health, and social well-being. Public health is different from many other fields of health as it focuses on preventing disease, illness and disability, and health promotion at the population level. Populations are groups of individuals with some similar characteristic(s) that unify them in some way, such as people living in rural areas, older people, women, an indigenous group, or the population of a specific region or country.

Contemporary public health is particularly concerned with the sections of the population that are typically under or poorly served by traditional health services, and consequently, most disadvantaged and vulnerable in terms of health. Importantly, public health is therefore concerned with the more distal (i.e., distant from the person) social, physical, economic, and environmental determinants of health, in addition to the more proximal determinants (i.e., closer to the person), such as risk factors and health behaviors.

Another distinction is often made between primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of prevention in public health. Primary prevention reduces the incidence of poor health by means such as vaccinations to prevent disease. Secondary prevention (or early detection) involves reducing the prevalence of poor health by shortening its duration and limiting its adverse social, psychological, and physical effects, such as different types of screening to identify a condition in the early stages. Tertiary prevention involves reducing the complications associated with poor health and minimizing disability and suffering, such as cardiac rehabilitation programs for patients after a heart attack. The boundaries between different levels of prevention are often indistinct and blurred, and a specific intervention strategy might simultaneously address the three different levels of prevention in different individuals.

The application of behavioral and social science theories and methods to improve health and prevent disease and disability at a population level can occur at multiple levels and in many different settings throughout society. Many public health initiatives are aimed at the individual or interpersonal level, and are delivered through the primary care setting, workplaces, and schools. Such programs typically have a low reach, in that only a limited number of people are involved in the programs and/or have access. However, these programs have high levels of exposure for the individuals in that they are quite intensive. Other programs can be organized and implemented through whole organizations or systems. Finally, communitywide or societal-level interventions may involve media, policy, or legislative action at a national or governmental level, and have a very large reach; however, program exposure is typically quite low.

The practice of public health is therefore very broad and can include the delivery of many different types of programs and services throughout the whole community. It can include efforts to reduce health disparities, increase access to health services, improve childhood rates of immunization, control the spread of HIV/AIDS, reduce uptake of smoking by young people, implement legislation and policies to improve the quality of water and food supplies, reduce the incidence of motor vehicle accidents, reduce pollution, and so on. In fact, the combined health of the population is more directly related to the quality and quantity of a country’s total public health effort than it is to the society’s direct investment in health services per se.

This research paper discusses the extent to which theories and models from the behavioral and social sciences inform our understanding and practice of public health. The paper provides a brief overview of the major public health problems and challenges confronting developed and developing countries; the contribution made by social and behavioral factors to many of these health problems; and how social and behavioral theories and models can be usefully applied to the development, implementation, and evaluation of public health programs.

1. Global Patterns Of Health And Disease: The Major Public Health Challenges

Disease burden includes mortality, disability, impairment, illness, and injury arising from diseases, injuries, and risk factors. It is commonly measured by calculating the combination of years of life lost due to premature mortality and equivalent ‘healthy’ years of life loss due to disability. The past 100 years have seen dramatic changes in health and the patterns of disease burden. Most countries have experienced an increase in life expectancy, with greater numbers of people expected to reach late adulthood. In the last 40 years, life expectancy has improved more than during the entire previous span of human history, increasing from 40 years to 63 years during 1950 to 1990 in developing countries (World Bank 1993). The number of children dying before five years has similarly reduced by 50 percent since 1960 (World Bank 1993).

Developed countries in particular have seen a decline in the proportion of deaths due to communicable and infectious diseases such as smallpox and cholera. However, this decline has occurred simultaneously with a marked increase in noncommunicable diseases, particularly the chronic diseases. In the early 1990s, the chronic diseases of ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease were identified as the leading causes of mortality, together accounting for 21 percent of all deaths in the world (WHO 1999). In 1998, 81 percent of the disease burden in high-income countries was attributable to noncommunicable diseases, in particular cardiovascular disease, mental health conditions such as depression, and malignant neoplasms, with alcohol use being one of the leading identified causes of disability (WHO 1999). Other major noncommunicable causes of death include road traffic accidents, self-inflicted injuries, diabetes, and drowning.

In developing countries, current major public health problems continue to include infectious diseases, undernutrition, and complications of childbirth, as well as the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases. Maternal conditions, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis are three of the major causes of disease burden for adults in developing countries (WHO 1999). Among children, diarrhea, acute respiratory infections, malaria, measles, and perinatal conditions account for 21 percent of all deaths in developing countries, compared with 1 percent in developed countries (WHO 1999). Developing regions account for 98 percent of all deaths in children younger than 15 years; the probability of death between birth and 15 years ranges from 1.1 percent in established market economies to 22 percent in sub-Saharan Africa (Murray and Lopez 1997). Importantly, many of these conditions are preventable; at least two million children die each year from disease for which vaccines are available (WHO 1999).

Accidents and injuries—both intentional and non- intentional—are a significant and neglected cause of health problems internationally, accounting for 18 percent of the global burden of disease (WHO 1999). In high-income countries, road traffic accidents and self-inflicted injuries are among the 10 leading causes of disease burden (WHO 1999). In less developed countries, road traffic accidents are the most significant cause of injuries, and war, violence, and self- inflicted injuries are among the leading 20 causes of lost years of healthy life (WHO 1999).

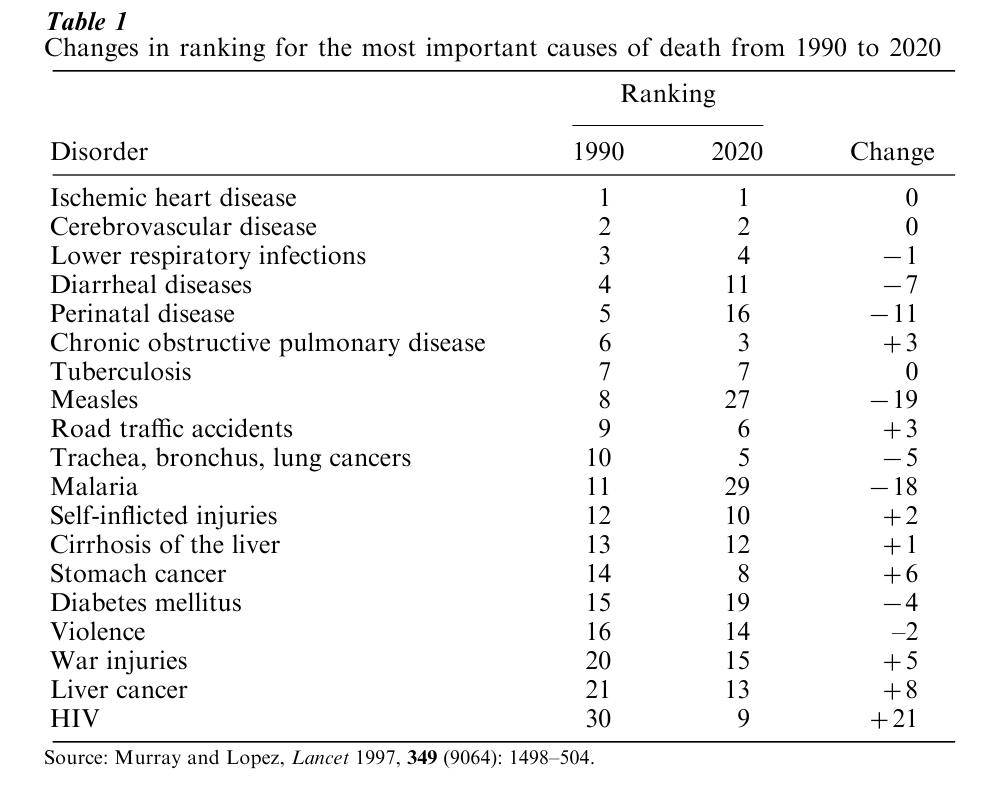

The Global Burden of Disease Study has projected future patterns of mortality and disease burden (Murray and Lopez 1997). Life expectancy is anticipated to increase notably in females to 90 years, with a lesser increase for males. Table 1 presents the changes in ranking for the most important causes of death. Worldwide mortality from perinatal, maternal, and nutritional conditions is expected to decline. Noncommunicable diseases are expected to account for an increasing proportion of disease burden, rising from 43 percent in 1998 to 73 percent in 2020. HIV will become one of the 10 leading causes of mortality and disability, and this epidemic represents ‘an unprecedented reversal of the progress of human health’ (Murray and Lopez 1997, p. 1506). The leading causes of disease burden will include ischemic heart disease, depression, road traffic accidents, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lower respiratory infections, tuberclerosis, war injuries, diarrheal disease, and HIV. Important health risk factors will include tobacco, obesity, physical inactivity, and heavy alcohol consumption. By 2020 tobacco is expected to cause more premature death and disability than any single disease, with mortality projected to increase from 3 million deaths in 1990 to 8.4 million deaths.

2. The Behavioral And Social Epidemiology Of Health And Disease

There are a multitude of factors that can be used to explain the changing patterns of morbidity, mortality, and the spread of diseases, both globally and between regions and countries. Some of these factors are related to population growth and aging and social patterns, while others are more related to changes in the local and global environment. An impressive amount of epidemiological evidence collected over the past 50 years has also identified the importance of a range of behavioral determinants and modifiable risk factors such as physical inactivity, smoking, and poor nutrition. The social and behavioral sciences are key disciplines underpinning public health as they have generated theories and models which provide a link between our understanding of these modifiable determinants of disease and health and strategies for disease prevention and health promotion.

The modern era for this evidence base began with the publication of the landmark study that investigated the relationship between British doctors’ smoking habits and disease (Doll and Hill 1964); the first reports from the Framingham Study that identified a number of ‘risk factors’ for cardiovascular disease (Kannel and Gordon 1968); and the United States Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health (US State Surgeon General’s Advisory Committee 1964). The Lalonde report (1974) and the Alameda County study (Belloc and Breslow 1972) both identified the importance of wider environmental factors such as social support, social networks, and socioeconomic factors as influences on health. In 1980, the United States Centers for Disease Control released a report estimating that 50 percent of mortality from the 10 leading causes of death in the United States could be traced to lifestyle factors (Centers for Disease Control 1980). McGinnis and Foege (1993) assessed the relative contribution of important and potentially alterable health behaviors and social factors to mortality and morbidity in the USA, and concluded that for approximately half of all deaths in 1990, the actual cause of death was attributable to health behaviors. In 1996, the report from the US Surgeon on Physical Activity and Health stated that physical activity reduced the risk of premature mortality in general, and of coronary heart disease, hypertension, colon cancer, and diabetes mellitus in particular (US Department of Health and Human Services 1996).

This rapidly expanding evidence base has been used by many countries for setting public health priorities and recommended goals and targets for addressing national public health challenges and reducing premature mortality and the burden of disease via changing lifestyle and related risk factors. Lifestyle factors targeted to influence population health include physical inactivity, diet, smoking, alcohol and other drug use, injury control, sun protective behaviors, appropriate use of medicines, immunization, sexual and reproductive health, oral hygiene, mental health, and many others.

Behavioral and social researchers have contributed to our understanding of the broad array of ecological, social, and psychological factors that influence lifestyle and health behaviors, and in turn, the etiology and pathogenesis of disease and health. In a recent edited series of monographs, Gochman (1997) provides an extensive overview of the range of environmental, cultural, family and personal factors that have been shown to influence lifestyle and health behaviors.

Moving more upstream from individual behaviors, there is also increasing interest in the ways in which the broader environment influences health, in particular the specific role played by social and economic factors. The Ottawa Charter (WHO 1986) recognized the importance of adopting a more social view of health by stressing that in order for public health programs to be effective they must incorporate the following elements: the development of personal skills; the creation of environments which are supportive of health; the refocusing of health and related services; an increase in community participation; and finally, the development of public policy which is health enhancing. The trend towards trying to understand more about the social, economic, and environmental determinants of health is probably one of the most fundamental developments to occur in mainstream public health over the past 20 years.

Recently there has been a very explicit research focus on socioeconomic health inequalities, social disadvantage, and poverty as major influences of health risk factors, disease, and reduced life expectancy. Poverty is undoubtedly one of the most important, single causes of preventable death, disease, and disability; the major variations and disparities in health observed both within and between countries can be explained to a large measure by social and economic disparities. Two key reports from the United Kingdom, the Black Report (Department of Health and Social Services 1980) and the Acheson Report (Acheson 1998), have emphasized the importance of these issues and ameliorative strategies.

Future social and behavioral epidemiological research into public health will need to address more adequately the multiplicity of factors contributing to health and disease. This will involve not only studying factors at the level of the individual, such as their beliefs and behavior, but also the full array of economic, social, environmental, and cultural factors as well.

3. Theories And Models For Prevention And Change

Social and behavioral theories and models not only help to explain health-related behavior and its determinants, they can also guide the development of interventions to influence and change health-related behavior and ultimately improve health. Theories can help understand adherence to a health regime, identify the information needed to develop an effective intervention program, provide guidelines on effective communication, and identify barriers to be overcome in implementing an intervention. While some theories are most usefully applied to understanding the role and influence of personal-level factors, others are more useful for understanding the importance of families, social relationships, and culture, and how these can be influenced in a positive fashion to promote improvements in health.

Models of individual health behavior such as the Health Belief Model and the Theory of Reasoned Action Planned Behavior, as well as models of interpersonal behavior such as Social Cognitive Theory, have been used widely in public health and health promotion over the past 20 years and are reviewed in various publications (e.g., Glanz et al. 1997). Staging models, such as the Transtheoretical Model, have often been used to improve the potency of health promotion programs (e.g., see Glanz et al. 1997). A combination of models or theories can often assist in the development of more individually tailored and targeted strategies.

While these theories and models focus primarily on achieving changes in health behaviors, other models are more concerned with communication and diffusion of effective programs, so as to benefit the health of a larger population. McGuire’s communication–behavior change model and Rogers’ diffusion of innovations model are examples of these types of theories (see Glanz et al. 1997). Health behaviors, and the broad array of environmental and social influences on behavior, are usually so complex that models drawing on a number of individual theories to help understand a specific problem in a particular setting or context are usually required to develop, implement, and evaluate effective public health responses. For example, Green and Kreuter’s PRECEDE–PROCEED model, social marketing theory, and ecological planning approaches are models and approaches that are used commonly in public health and health promotion (see Glanz et al. 1997).

However, within the behavioral sciences, much less attention has been given to models or theories that understand change strategies and programs within the broader environment, groups, organizations, and whole communities. This is despite increasing research evidence indicating that social and environmental factors are critically important in understanding individual attitudes, behavior, and health. The design of programs to reach populations requires an under- standing of how social systems operate, how change occurs within and among systems, and how large-scale changes influence people’s health behavior and health more generally. A combination of theories and models of individual behavior can be used to shift the focus of intervention strategies beyond a clinical or individual level to a population level by their application via a range of settings in the community, such as the workplace and primary health care (Oldenburg 1994). This increases the reach of intervention programs beyond a relatively small number of individuals. Many of the social and behavioral theories or models that have been used extensively to understand and describe change at an individual or small group level can also inform our understanding of the change and diffusion process at an organizational or population-based level.

4. Wider Implementation Of The Social And Behavioral Science Evidence Base In Public Health

With the development, implementation, and evaluation of a series of major community-based cardiovascular prevention trials during the 1970s and 1980s, widespread use was made of multilevel intervention or change strategies underpinned by behavioral and social science theories and research for the first time. Importantly, these strategies did not focus exclusively on change in the individual. Instead, preventive strategies using multiple approaches were directed at the media, legislation, and the use of restrictive policies, and involved specific settings such as schools, the workplace, health care settings, and other key groups in the community, with the aim of reducing population rates of risk behaviors, morbidity, and mortality.

The North Karelia Project in Finland (Puska et al. 1985) was initiated in response to concern that the community, at that time, had the highest risk of heart attack worldwide. Strategies included tobacco taxation and restriction, televised instruction in skills for nonsmoking and vegetable growing, and extensive organization and networking to build an education and advocacy organization. After 10 years, results indicated significant reductions in smoking, blood pressure, and cholesterol, and a 24 percent reduction in coronary heart disease mortality among middle-aged males. The Stanford Three Community Study (Farquhar and Maccoby 1977) demonstrated the feasibility and effectiveness of mass media-based educational campaigns and achieved significant reductions in cholesterol and fat intake. The Minnesota Heart Health Project (Mittelmark et al. 1986), the Pawtucket Heart Health Program (Lefebvre et al. 1987), and the Stanford Five-City Project (Farquhar et al. 1990) used interventions aimed at raising public awareness of risk factors for coronary heart disease, and changing risk behaviors through education of health professionals and environmental change pro- grams, such as grocery store and restaurant labeling.

Worksite intervention trials, such as the Working Well Trial (Sorensen et al. 1996) and an Australian study with ambulance workers (Gomel et al. 1993), have utilized interventions aimed at favorably altering social and psychological factors known to influence health-related behaviors, including increased aware- ness of benefits, increased self-efficacy, increased social support, and reduced perception of barriers. Strategies in this setting can include promotion of nonsmoking policies, increasing the availability of healthy foods in canteens and vending machines, group education sessions, and access to exercise facilities. School-based interventions provide an established setting for reaching children, adolescents, and their families to address age-pertinent health issues such as smoking, teenage pregnancy, and substance use. Strategies have targeted social reinforcement, school food service, health related knowledge and attitudes, local ordinances, peer leaders, and social norms.

5. Evaluation Of Public Health Intervention Trials

In evaluating the effectiveness of such trials, Rose (1992) states that it is important to acknowledge the differences between clinical and more population-based approaches. Clinical approaches, while more likely to result in greater mean changes in individuals, are less significant at a population level because fewer individuals are involved. In contrast, the small mean changes achieved by population-based approaches, if applied to a large number of people, have the potential to impact much more significantly on population rates of disease and health.

One of the difficulties in evaluating population-based approaches is the length of time required to demonstrate changes in population rates of health outcomes. While researchers can readily measure changes in a behavioral outcome—such as the rate of smoking cessation—following a widespread and well-conducted program, the time required for such behavioral changes to impact upon long-term morbidity and mortality—such as lung cancer—is much more problematic. Nevertheless, many of the above identified behavior-based trials demonstrate the value of social and behavioral theories and the feasibility of activating communities in the pursuit of health.

6. Diffusion And Dissemination Of The Evidence Base

The ultimate value of this research must be determined by the extent to which the knowledge generated is widely disseminated, adopted, implemented, and maintained by ‘users,’ and ultimately, by its impact on systems and policy at a regional, state, and/or national level (i.e., institutionalization). While considerable effort and resources have been devoted to developing effective interventions, relatively little attention has been given to developing and researching effective methods for the diffusion of their use. It is important to acknowledge that the availability of relevant research findings does not in itself guarantee good practice. Such knowledge transfer involves the development of formal research policies, formalized organizational structural support, appropriate and targeted funding, formal monitoring of activity, and ongoing training.

In essence, achieving the effective diffusion of innovations, both within the general community and in organizational settings, involves change, and the change principles which underpin the diffusion process are not so different to those previously identified for understanding change at the individual, organizational, or community levels (see Oldenburg et al. 1997). At the level of the individual, family, or small group, uptake of a health promotion innovation typically involves changes in behaviors or lifestyle practices which will either reduce risk factors or promote health. At an organizational level, such as the workplace, school, or the health care setting, successful uptake of an innovation may require the introduction of particular programs or services, changes in policies or regulations, or changes in the roles and functions of particular personnel. At a broader community-wide or even societal level, the change process can involve the use of the media and changes in governmental policies and legislation, as well as coordination of a variety of other initiatives at the individual and the settings level.

However, in considering the principles that underpin the diffusion of innovations at a population level, further complexity arises from the need to consider change occurring at multiple levels, across many different settings, and resulting from the use of many different change strategies. This requires the application of multiple models and theories in order to develop frameworks with sufficient explanatory power.

7. Looking To The Future

It is difficult to be certain about the public health challenges that lie ahead in this new millennium. In all countries, there is a need to reduce preventable disease and premature death, reduce health inequalities, and develop sustainable public health programs.

Much of the social and behavioral science research that has been conducted with individuals is still relevant in the field of public health, as are many of the models and theories that have been developed and tested over the past 30 years. To move to a population-based focus, we need innovative means of implementing such knowledge and methodologies so as to increase the reach of such programs to more people, particularly those individuals and sections of society who are most disadvantaged.

Adopting a preventive approach to health, acknowledging and acting on the importance of social and environmental factors as major determinants of population health, and reducing health inequalities provides a substantial challenge to public health in the coming years. Furthermore, limited resources place an added emphasis on evaluating the affordability and sustainability of public health interventions. Public health should be at the forefront of developing and researching effective intervention methods and strategies for current and future health challenges, with global sharing of information in terms of monitoring health outcomes and development of the evidence base. However, this research should not focus solely on developing strategies and testing their efficacy and effectiveness. There is an urgent need for research that examines larger-scale implementation and diffusion of these strategies to whole communities and populations, through the innovative use of a variety of psychological, social, and environmental intervention methods, including evidence from the social and behavioral sciences.

Bibliography:

- Acheson D 1998 Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health. The Stationary Office, London

- Belloc N B, Breslow L 1972 Relationship of physical health status and health practices. Preventive Medicine 1: 409–12

- Centers for Disease Control 1980 Ten Leading Causes of Death in the United States 1977. US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

- Department of Health and Social Services 1980 Inequalities in Health: Report of a Research Working Group Chaired by Sir Douglas Black. DHHS, London

- Doll R, Hill A B 1964 Mortality in relation to smoking: Ten years’ observations of British doctors. British Medical Journal Vol.(i): 1399–410

- Farquhar J W, Wood P D, Breitrose H 1977 Community education for cardiovascular health. Lancet 1: 192–5

- Farquhar J W, Fortmann S P, Flora J A, Taylor C B, Haskell W L, Williams P T, Maccoby N, Wood P D 1990 Effects of community-wide education on cardiovascular risk factors: The Stanford Five-City Project. Journal of the American Medical Association 264: 359–65

- Glanz K, Lewis F M, Rimer B K (eds.) 1997 Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. JosseyBass, San Francisco, CA

- Gochman D S (ed.) 1997 Handbook of Health Behavior Re- search. Plenum, New York

- Gomel M, Oldenburg B, Simpson J, Owen N 1993 Worksite cardiovascular risk reduction: A randomised trial of health risk assessment, education, counselling, and incentives. American Journal of Public Health 83: 1231–8

- Kannel W B, Gordon T 1968 The Framingham Study: An Epidemiological Investigation of Cardiovascular Disease. US Department of Health Education and Welfare, Washington, DC

- Lalonde M 1974 A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians: A Working Document. Government of Canada, Ottawa, ON

- Last J M 1995 A Dictionary of Epidemiology. Oxford University Press, New York

- Lefebvre R C, Lasater T M, Carleton R A, Peterson G 1987 Theory and delivery of health programming in the community: The Pawtucket Heart Health Program. Preventive Medicine 16: 95

- McGinnis J M, Foege W H 1993 Actual causes of death in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association 270: 2207–12

- Mittelmark M B, Luepker R V, Jacobs D R 1986 Communitywide prevention of cardiovascular disease: Education strategies of the Minnesota Heart Health Program. Preventive Medicine 15: 1–17

- Murray C J L, Lopez A D 1997 Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 349(9064): 1498–504

- Oldenburg B 1994 Promotion of health: integrating the clinical and public health approaches. In: Maes S, Leventhal H, Johnston M (eds.) International Review of Health Psychology. Wiley, New York pp. 121–44

- Oldenburg B, Hardcastle D, Kok G 1997 Diffusion of innovations. In: Glanz K, Lewis F M, Rimer B K (eds.) Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA

- Puska P, Nissinen A, Tuomilehto J, Salonen J T, Koskela K, McAlister A, Kotke T E, Maccoby N, Farquhar J W 1985 The community-based strategy to prevent coronary heart disease: Conclusions from ten years of the North Karelia Project. Annual Review of Public Health 6: 147–93

- Rose G 1992 The Strategy of Preventive Medicine. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Sorensen G, Thompson B, Glanz K, Feng Z, Kinne S, DiClemente C, Emmons K, Heimendinger J, Probart C, Lichtenstein E 1996 Worksite based cancer prevention: primary results from the Working Well Trial. American Journal of Public Health 86: 939–47

- US Department of Health and Human Services 1996 Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health, Washington, DC

- US State Surgeon General’s Advisory Committee 1964 Smoking and Health. US Department of Health, Washington, DC

- The World Bank 1993 World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health. Oxford University Press, New York

- World Health Organization 1986 The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Health Promotion International 1(4): iii–v

- World Health Organization 1964 World Health Organization Constitution. WHO, Geneva

- World Health Organization 1999 World Health Report: Making a Diff WHO, Geneva