View sample public health research paper on justice in public health. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Public health measures have contributed dramatically to reducing the death rate and extending life expectancy in populations. Because of their success, their value is broadly acknowledged, at least in public discussion. Nevertheless, claims for the allocation of societal funds to public health projects are always in competition with claims for projects of other sorts. Ideally, broad considerations of justice should determine how a society’s funds are allocated among the important needs for expenditures on social goods such as public health, education, defense, safety, transportation, law enforcement, the arts, and clinical medicine. Yet, the issues of justice persist even when we focus solely on a single domain. Within public health, we are challenged to decide how limited funding resources should be sorted out: Which projects should be addressed first? How much should be allocated to which efforts? What sorts of considerations should be taken into account and which factors should be ignored? Should all of the funds be directed at providing immediate benefits, or should some resources be allotted to prepare for future possible public health needs or to public health research? In times of urgency and need, how should limited supplies be allocated? Which populations should be rescued when all cannot be? How should the multitude of competing claims be prioritized?

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

In developing an understanding of justice in public health, focus on disasters and emergencies can be instructive because the circumstances make the importance of resource allocation vivid and pressing. Such circumstances dramatize the need for thinking clearly about justice in setting public policy and they can teach us how to conceptualize public health allocations even when there is no imminent disaster. This research paper reviews the leading theories of justice in medicine and then goes on to explain some principles of justice in public health by focusing on recent disasters that are familiar to everyone: The allocation of public health resources after the attack on the World Trade Center in New York City in September 2001, the flu vaccine shortage in the fall of 2004, and Hurricane Katrina in September 2005. A careful analysis of these dramatic examples explains the factors that make some allocations and policies just and others unjust. When public health resources are well allocated, the principles that underlie the decisions are assumed with relatively little contention. Implicit in this silent agreement are the presumptions (1) that everyone knows ‘the’ guiding principle of justice and (2) that ‘the’ principle has the solid endorsement of a broad majority of the population. Yet, a comparison of the principles most commonly invoked in discussions of justice reveals that there is no single principle that supports all of the relevant policies. No simple formula can tell us what justice requires in all circumstances. Rather, careful investigation and examination of the situation, and thoughtful reflection on the array of problems involved and the consequences of choosing one path or another suggest that justice requires distributions based on different principles in different contexts.

Prominent Conceptions Of Justice

In his lengthy discussion of justice in book 5 of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle equates justice to the entirety of interpersonal virtue while also acknowledging its complexity and contextuality. Aristotle defined justice as giving each his due and treating similarly situated individuals similarly. Yet, he acknowledged the complexity involved in determining which features should be taken into account in deciding that individuals are similarly situated and which of the generally important factors should be given priority in a particular situation. According to Aristotle, factors such as relationship, history, consequences, and feasibility are all considerations that may determine which allocation is just in a situation, but justice does require equality in the treatment of equals.

Although some contemporary philosophers follow Aristotle’s insights and recommend an account of justice that draws on an array of reasons, those who write on issues of justice and health care appear to prefer a more Platonic approach and attempt to articulate a singular comprehensive account of justice. Consider the following competing contemporary accounts of justice that enter discussions of medicine and public health.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism has a long history in ethics, tracing back to the writings of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. Today utilitarianism appears to be the dominant view of justice in medical and public health policy. It is the view that justifies policies that produce the best outcomes. For example, policies that aim at the maximization of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), or disability-adjusted life expectations (DALEs) are all utilitarian.

Utilitarian allocations aim at maximizing an outcome over a population. A utilitarian conception of justice is committed to treating people as equals and to deliberately ignoring relational and relative differences between individuals. Hence, utilitarians aim at producing the most of the desired results for the entire population that is to be governed by the policy. Utilitarians identify an objective standard for calculating outcomes, and employ that standard in policy decision. A policy is just on utilitarian grounds when it is the most likely to produce the greatest amount of the specified end, that is, it is efficacious. In the domain of medicine, utilitarians focus on measurements of health or life span. A cost–benefit analysis of the same considerations is employed to determine the policy for a population.

John Rawls

Since 1971, many of the positions on justice espoused by philosopher John Rawls, first in A Theory of Justice (1971) and later in Political Liberalism (1993) and other works, have come to play a significant role in public deliberation about nonutilitarian criteria for justice in society and the allocation of medical resources. One Rawlsian concept that has received especially broad endorsement in the medical ethics literature is fair equality of opportunity. The other concept that has been widely adopted is the difference principle, and people who have embraced some version of that principle now refer to such views as prioritarianism. These principles exemplify features of Rawls’s view of what a liberal political conception of justice should include.

Rawls’s two principles of justice provide ‘‘guidelines for how basic [political] institutions are to realize the values of liberty and equality’’ and assure all citizens ‘‘adequate all-purpose means to make effective use of their liberties and opportunities,’’ as he writes in Political Liberalism (Rawls, 1993: 4). Together these principles specify certain basic rights, liberties, and opportunities and assign them priority against claims of those who advocate for the general good or the promotion of perfectionism (i.e., the best possible society).

Rawls (1993: 184) himself does not extend his principles of justice to health and medical care. In fact, he specifically maintains that ‘‘variations in physical capacities and skills, including the effects of illness and accident on natural abilities’’ are not unfair and they do not give rise to injustice so long as the principles of justice are satisfied. Yet, several prominent authors who write about justice and medicine discuss medical allocations by invoking Rawls’s principles and they extend particular Rawlsian concepts to medicine.

According to Rawls’s first principle, justice requires a liberal democratic political regime to assure that its citizens’ basic needs for primary goods are met and that citizens have the means to make effective use of their liberties and opportunities. Rawls’s second principle regulates the basic institutions of a just state so as to assure citizens fair equality of opportunity. The first principle has priority over the second in that it requires political institutions to provide whatever citizens must have in order to understand and to exercise their rights and liberties. According to Rawls, his two principles taken together assure such basic political rights and liberties as liberty of conscience, freedom of association, freedom of speech, voting, running for office, freedom of movement, and free choice of occupation. They also guarantee the political value of fair equality of opportunity in the face of inevitable social and economic inequalities. Both principles, therefore, express a commitment to the equality of political liberties and opportunities.

In Rawls’s account, the difference principle is the second condition of the second principle of justice. Recognizing that economic and social inequalities are an unavoidable feature of any ongoing social arrangement, his second principle expresses the limits on unequal distributions. He holds that equal access to opportunities is a necessary feature of a just society, and then, so as to compensate for eventual disparities and to promote persisting equality of opportunity, he calls for corrective distribution measures through application of the difference principle. As Rawls (1993: 6) states the principle, ‘‘Social and economic inequalities … are to be to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged members of society.’’ In other words, governmental policies that distribute goods between citizens must be designed to rectify inequality by first advancing the interests of those who are otherwise less well off than their fellow citizens.

Norman Daniels And Fair Equality Of Opportunity

Norman Daniels has used the Rawlsian concept of fair equality of opportunity to argue that health care should be treated as a basic need. He maintains that ‘‘[h]ealth care is of special moral importance because it helps to preserve our status as fully functioning citizens’’ (Daniels, 2002: 8). Daniels wants us to count at least some medical services as primary goods so that they are ‘‘treated as claims to special needs.’’ From Daniels’s point of view, therefore, the allocation of health-care resources should aim at equalizing social opportunity.

Daniels expects his claim to lead to the conclusion that a just society should provide its members with universal health care, including public health and preventive measures. Yet, recognizing that a society will limit the amount of health care it provides, Daniels proposes ‘‘normal species function’’ as the benchmark for deciding which care to provide. He holds that health care that will restore or maintain normal species function should be provided. Nothing has to be provided, however, for those who are already within the normal range. Furthermore, Daniels points to the many social determinants of health inequalities and invokes Rawls’s difference principle to claim that a just society should provide the most health care to those who are most disadvantaged with respect to health.

Prioritarianism

Prioritization, which builds on Rawls’s difference principle, stands in opposition to utilitarian approaches to the distribution of scarce resources. Whereas utilitarian allocations aim at the maximization of an outcome over a population and deliberately ignore the relational and relative differences between individuals, prioritarian allocations aim at the identification of unwanted inequalities and then distribute resources so as to compensate for or correct them. Prioritarian allocations reflect a concern for how individuals fare in relation to each other and attempt to advantage those whose position is worse than others’.

Numerous papers in the bioethics literature address the conflict between prioritarian concerns and utilitarian cost-effectiveness analysis in the allocation of medical resources. For instance, Dan Brock (1998, 2002), Frances Kamm (1993, 2002), and David Wasserman (2002) argue the merits of one approach over the other in a variety of vexing cases. They reflect on the difference between policies that will save the lives of some people or save an arm for some other people. They are concerned with whether public policies should provide a greater advantage to some who are already well off (e.g., save the lives of the able-bodied), or provide a smaller advantage to some who are worse off (e.g., save the use of an arm for a group with some other preexisting disability). These tragic choices discussions aim at discovering a principled basis for making decisions by sometimes focusing on identifiable individuals, and sometimes not. They sometimes address trade-offs of future significant harms against present small harms or more certain imminent harms against more hypothetical distant harms. Typically, these discussions favor policies that will allocate resources to immediate needs over future needs and benefits to identifiable individuals over benefits to those who cannot be currently identified.

Public Health Models That Challenge Popular Theories Of Justice

In light of these competing theories of justice, it is illuminating to scrutinize some of the public health policies that were implemented in the fall of 2001. Consider two examples.

Medical Emergencies

Triage is the broadly endorsed approach for responding to medical emergencies. It is the approach that was immediately adopted by health-care workers on September 11, 2001 for dealing with the medical needs that were expected once the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center collapsed, and its appropriateness has not been challenged in any of the subsequent literature. Triage is the public health model for responding to domestic medical emergencies that requires health-care professionals to make judgments about the likely survival of patients who need medical treatment. Recognizing that some people have urgent needs (i.e., they will die or suffer significant harm if not treated very soon) and that the resources available are scarce (e.g., supplies, facilities, trained personnel), patients are sorted into three groups and they are either treated, put aside, or asked to wait according to their group classification. Those who are not likely to survive are deprived of treatment so that the available resources can be used to save the lives of those who are more likely to live. Those who are likely to die without treatment but who are likely to live if treated promptly are treated first. Those who are in need of treatment but who can wait longer without dying are treated after those who are urgently ill. On the morning of 9/11, the disaster plan that had previously been developed and practiced was implemented at hospitals in the New York vicinity. Many beds in intensive care units (ICUs) were emptied. Elective surgery was canceled. Patients who could have been sent home were discharged. Collection activities in blood banks went into high gear, but they were only accepting type O– donors.

In medical emergencies, health-care professionals deliberately disregard the concepts of giving everyone a fair equal opportunity to receive medical treatment, and they also pointedly ignore relative differences in economic and social standing. Instead, they focus exclusively on the medical factors of urgency of need and the likelihood of survival. No one presumes to measure whether or not each patient has previously received a fair or equal share of available resources, and no one stops to assess who has been more or less advantaged. No one sorts out the small differences between individuals that would provide somewhat greater utility from one allocation rather than another. And no one criticizes medicine for not attending to those differences (Rhodes, 2001). (I have argued generally that physicians have a role-related responsibility to avoid making judgments about patients’ worthiness and that they must treat all patients similarly based on medical considerations.) In fact, the long tradition of medical ethics, dating back at least to the Hippocratic tradition, requires physicians to provide treatment based on need. Hence the ethics of medicine appears to require physicians to commit themselves to unequal treatment (since need is unequal) and also to the nonjudgmental regard of each patient’s worthiness.

Research And Public Health

Biomedical research and public health policies typically focus on populations. Biomedical research attempts to disconfirm hypotheses about predicted outcomes and thereby to develop facts about the response of organisms with certain common characteristics. With respect to human-subject research, groups of people are selected for study because of some relevant biological or environmental similarities. Any knowledge gained from the process is useful to the extent that it is applicable to all of those who share the common condition.

Public health policies are also designed to have an impact on all, and only, those individuals who are similarly impacted by a disease or a health-related condition. In deliberately focusing on one affected group or another, biomedical research and public health policies typically provide benefits only to the target group. The goals of biomedical research and public health are pointedly directed at everyone in the group that might benefit from them. By looking back at outcomes, researchers attempt to develop knowledge about biological or psychological reactions. By looking toward the future, public health officials attempt to develop a generalizable approach to the prevention, reduction, or treatment of biological or psychological problems. (Although a subject for biomedical research may disproportionately affect a relatively disadvantaged population (e.g., the effect of lead paint on child development), the study findings and the subsequent public health policies will have implications for all of those who have been or who may be affected.) As with medical triage in the emergency setting, biomedical research and public health have not been criticized for holding to these agendas.

Because ideas about justice and medicine are typically discussed singly, in artificially isolated contexts and with a focus on carefully selected examples, it is hard to notice when and how their underlying conceptions clash. Yet, the broad consensus on emergency triage, public health research, and public health policy provide an occasion to consider justice across a broad spectrum of medical contexts. These examples also challenge the assumption that a consensus supports a single principle of justice in medicine and public health. As Ronald Green has noted in his criticism of Daniels, the ‘‘mistake … is trying to decide such matters by reference to a single consideration – and not necessarily the most important one’’ (Green, 2001).

Consequentialist considerations of efficacy and equality support well-accepted views on emergency triage. When the time constraints of an emergency and the needs for medical resources significantly outstrip the available resources, responses should be based on efficacy and treating all with similar medical needs similarly. The sweeping exclusions of triage represent the goal of avoiding the worst outcome more than the utilitarian aim of maximizing the greatest utility, particularly when utility might require fine-grained sorting and ranking. Triage, therefore, is not entirely compatible with utilitarianism, nor is it consistent with either fair equality of opportunity or prioritarianism. These different principles (avoid the worst outcome, maximize utility, fair equality of opportunity, and prioritarianism) cannot all be appropriate for guiding the same allocation decisions.

The intuitions supporting the view that priority should be given to equalizing social opportunities or to providing the greatest benefit to the least advantaged are undermined by the strong sense that nonmedical relative differences should not come into play in decisions about emergency responses. This invites questions about the appropriate framework for policy decisions about public health needs and setting the research agenda. Emergency triage allocates resources by taking everyone’s prognosis and expected outcome into account. Individuals certainly get unequal lots and no priority is allowed to those who are more generally worse off.

Similarly, public health research sometimes has no impact on the social participation, health, or longevity of the entire population. If it turns out that we never have another disaster similar to what occurred on September 11th, if we never again experience a catastrophe that creates enormous amounts of pulverized concrete and incinerated computers and office furniture, research on their effects may never promote the social participation or health of anyone. Or, if the burdens of the interventions that the studies support turn out to be prohibitively costly (e.g., give up skyscrapers and computers), they will not be adopted and no one’s fair equality of opportunity will be advanced. Public health research involves a quest for information that may or may not be useful. It also sometimes directs resources to the needs of the relatively few affected individuals. So, the standards of promoting fair equality of opportunity or maximizing health may not quite fit. If fair equality of opportunity was the only consideration to be taken into account, many other uses of resources would always have preference over public health research. Yet, the consensus in favor of such research suggests that other reasons support its broad endorsement.

Furthermore, while public health policies sometimes meet the standard of promoting utility, or fair equality of opportunity, or priority for the worse off, sometimes they do not. In sum, broadly endorsed public health policies suggest that emergency triage, public health research, and public health policy rely on more than a single principle of justice.

A Lesson From Experience

The incongruity between policy consensus on the one hand and lauded principles of justice on the other suggests that there is a mistake in our search for ‘the’ ruling principle of justice. It also suggests an alternative for looking at the problem of justice. When we stop to examine our own thinking about these issues, we notice that we actually invoke different reasons to support different principles and different rankings of considerations in different contexts. That insight suggests that there is no obvious reason to presume that a single principle defines justice. With sensitivity to the complexity of human values and to the different contexts of medical and public health policies, we can appreciate that a variety of reasons justify public health resource allocations. Even though such a contextual approach to determining the just distribution of resources will sometimes favor one principle and at other times rely upon another, decisions can express a widely shared view about the primacy of one consideration over another and reflect reasons that no one can reasonably reject. In this sense, a contextual view of justice is not random and not idiosyncratically subjective. Rather, it expresses deep similarities in human concerns and shared priorities that relate to our human mortality and vulnerability.

The Flu Vaccine Shortage And Hurricane Katrina

Before enumerating a list of principles of justice for guiding public health allocations, consider the flu vaccine shortage in the fall of 2004 and Hurricane Katrina in the fall of 2005. In 2004, people recognized that it was important to find a better way to allocate the limited supply of flu vaccine than to allow it to go to those with good connections, the aggressive, and the lucky. Communities and then the U.S. Centers for Disease Control promulgated distribution policies that allotted the vaccine to those who were likely to die or suffer serious harm if they contracted the disease, and then they implemented schemes to restrict distribution accordingly. The supply was therefore directed to the immunocompromised, the very young, pregnant women, the elderly, and health-care providers who would be called upon to treat affected individuals.

These policies were very broadly endorsed and achieved excellent compliance. The almost total absence of debate over their implementation was evidence of the extent of the consensus. Aside from the advocates for children and the elderly who each argued that their constituent group should have even more priority over others in the vaccine target group, the U.S. population accepted the plans that were implemented.

The principle supporting the flu vaccine allocation was not utilitarian because utility alone would have disqualified those with only a short remaining life span because vaccination for the elderly and the immunocompromised could be expected to provide a low QALY payoff. Neither did the policy consider previous injustices or disadvantages in the allocation so as to give priority to the least well off, nor did it try to equalize opportunities in some wider sense. The principle inherent in the vaccine distribution policy was avoid the worst outcome, that is, avoid the most deaths and serious illnesses. The consensus of support and the lack of opposition speaks to how the importance of one particular goal can be apparent.

Reaction to what happened before, during, and after Hurricane Katrina illustrates a broad consensus at the other end of the spectrum. In the case of Katrina, there was general agreement that the U.S. government had failed to adequately prepare for the disaster, failed to warn and protect Gulf Coast residents, failed in its attempts at rescue and meeting the tremendous needs of affected communities in the aftermath, and failed in providing honest and timely communication about the formaldehyde risk of the trailers later provided to shelter some of those left homeless. These realizations point us to further broad agreement on the importance of investment in disaster preparedness, of meeting the urgent needs of all citizens, of making leadership appointments based on qualifications rather than cronyism and politics, of timely and honest communication. Again, this consensus on values is not a matter of chance coincidence, it reflects the central importance of key human concerns.

Justice In Allocations For Public Health

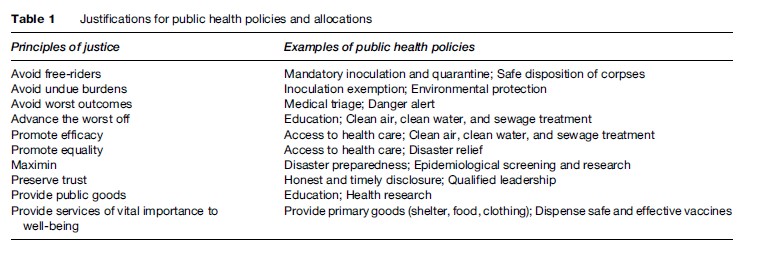

We all are vulnerable to death, pain, illness, and disability, and we all want to avoid those consequences for ourselves and our loved ones. We also all have to acknowledge that there are not enough resources to provide for all of the public health projects that we would like. Hence, we recognize the necessity of prioritizing our values and sacrificing some of what we would like to have so that we can be more likely to secure those things that are more important to us. Because the achievement of certain goals is essential to our enjoying others, because certain hardships are more enduring and painful than others, and because this is so for almost everyone almost always, people tend to agree on the primacy of some important concerns. These features of our shared human nature make the concordance on some matters of public health not contingent and coincidental, but a genuine agreement expressing the human importance of some feature of a situation. This natural consensus provides us with an array of principles of justice that are relevant to any consideration of justice and public health (see Table 1).

Triage may be the appropriate guiding conception of justice for policies that respond to large-scale emergency situations. The justification for triage is that it is the policy most likely to avoid the worst outcome and to save the greatest number of lives. Reasonable people would want to survive a disaster and they would want their loved ones to survive. Foregoing treatment for those who are least likely to survive so as to provide the best chance of survival to the most people yields the result that everyone wants most. (In this analysis I am drawing freely on T.M. Scanlon’s conception of justice (Scanlon, 1998)). So long as the same criteria for treatment are applied to everyone, the loved ones of those from whom treatment is withheld should not complain of injustice. Because hypothetical consent to triage policies can be legitimately presumed, a triage allocation of emergency services is not likely to undermine social stability.

Disaster preparedness requires the allocation of communal resources for research, training, and equipment. Policies to allocate resources for preparedness and research are justified because the ability to respond efficiently could crucially depend on preparedness and the information learned from studies. The goods that can be had would not be available without the prior contribution from a common pool. Hence, it is reasonable to provide some resources for preparedness and research to increase the chance for a good outcome and to minimize the chance for the worst outcome (i.e., maximin).

In the face of a credible risk of biological warfare, mandatory inoculation against a serious contagious disease is an appropriate policy when a reasonably safe and effective vaccine is available. Reasonable people would endorse such required inoculation because it provides protection from the disease, that is, it provides a public good that everyone values. Everyone should, therefore, bear a fair share of the burden of safety. Those who might refuse to comply would be free-riders, ready to treat others unjustly by taking advantage of their good will and sense of communal responsibility. Public health measures are similarly justified by the public good of protection against disease that they provide and by the anti-free-rider principle that would prohibit unsafe practices. And when it comes to actually dispensing vaccine in the face of a credible risk, because the relative differences between individuals may not be significant enough to be taken into account, a distribution scheme based on equality, such as a lottery or first come first serve, may be required.

Furthermore, with respect to public health measures like vaccination, there may be good reasons for allowing a few to be exempt. Those who are especially vulnerable to the inherent dangers of immunization – for example, those with impaired immune systems – would bear more than the typical burden of being vaccinated. If everyone else in the society was inoculated, exempting those few who would otherwise bear an undue burden, would not increase the risk for others.

The public health concerns after September 11th and Hurricane Katrina reflect three slightly different principles. Clean air, clean water, and sewage treatment are the kinds of public goods that everyone needs constantly. Their vital and constant importance to everyone’s wellbeing is a justification for policies to provide and protect them. In many settings, clean air, clean water, and sewage treatment are also the kinds of benefits that no one can have unless everyone has them, and making them available or unavailable at all makes them available or unavailable to everyone in the society. In many situations, these are also services that can be provided with greatest efficacy by providing them for everyone.

Another important consideration is also relevant to the endorsement of public health interventions that provide for everyone’s vital and constant needs. Such interventions are likely to make the greatest difference in health and wellbeing for the economically and socially least advantaged. The well-to-do could leave town for the clean air of the country or simply purchase gas masks to protect themselves from air pollution. They would also have the wherewithal to purchase bottled water, to dig private wells, and to install private sewage systems. The well-to-do would be better off with the general availability of clean air, clean water, and sewage treatment. Yet, the underlying interrelation between poverty and disease and the consequent disparity between the well-to-do and the poor with respect to health status and life expectancy (Daniels, 2002; Sheehan, 2002; Smith, 2002) suggest that the economically and socially disadvantaged would enjoy an even greater benefit from policies that made these benefits generally available. Furthermore, the continuous lack of such basic goods as clean air, clean water, and sewage treatment for some, while others enjoy them as private resources, could promote social instability. The difference principle is, therefore, an additional reason for adopting public health measures to provide these services. It justifies the same policies that would be supported by the vital importance of the services and the fact that such services are most feasibly supplied to all at once (i.e., efficacy). This example, therefore, illustrates how different principles can be just and converge in support of public health policies.

Overview

To the extent that policy domains covered by different principles can be legitimately distinguished, a variety of appropriate and compelling principles can express the complex and varied considerations that make different policies just. The just allocation of medical and public health resources is and should be governed by a variety of considerations that reasonable people endorse for their saliency.

Several principles of justice have a legitimate place in medical and public health allocation, and the just solution to practical problems in public health should be guided by meeting mutually supported and compelling concerns. The principles of justice include: the anti-free-rider principle, avoid undue burdens, avoid the worst outcome, the difference principle, efficacy, equality, maximin, provide public goods, and the vital and constant importance to well-being. (I do not claim that this list is a full elaboration of the relevant considerations for justice in medicine and public health.) To the extent that the scarcity of resources makes it impossible to fulfill all of the legitimate claims for a society’s allocation of resources, some principle(s) will have to be sacrificed and some projects that are supported by compelling reasons will have to be scaled down from an ideal level, delayed, or abandoned. When these hard choices have to be made, they too should be made for good reasons that reasonable people would support. Daniels’s relevance condition appears to capture this aspect of policy setting (Daniels, 2002: 16). In making difficult choices about the ranking of projects and priorities and the design of policies, different considerations will have different levels of importance in different kinds of situations. There is no obvious reason to presume that one priority will always trump the others. When the priority of a principle reflects the endorsement of an overlapping consensus of reasonable people, the justice of the policy is clear. When large groups of people rank the competing considerations differently, a significant consensus on the principles that are irrelevant may emerge and that consensus can serve as the basis for just policy. To the extent that flexibility can be supported by the available resources, policies should show tolerance for different priorities.

As a general caution, however, public health policy makers need to be alert to the kinds of illegitimate considerations that can distort and pervert any policy. Common psychological tendencies can interfere with judgment. For example, human psychology inclines people to exaggerate the impact of a loss and also inclines people to underappreciate the value of future goods. Prejudice, stereotyping, the desire to do something, pressing needs made vivid by individual cases, lack of insight, and lack of foresight are other common psychological inclinations that can distort judgment and lead to unjust public health policies. Furthermore, politics and personal gain may be motivating elements, but they do not promote reasonable public health policy. And then there is greed, which can be camouflaged under seemingly acceptable justifications.

Our recent experience has also taught us lessons about communication and trust and their importance in the design and implementation of just public health policies. After the fall of the World Trade Center Twin Towers, public health officials from the Environmental Protection Agency and government representatives failed to honestly communicate about the danger and misled the public about the air quality and the need for protection from the toxic environment. Today, thousands of people who worked at the site are ill and dying, at least in part because of the failures to provide full and honest disclosure (DePalm, 2006, 2007). Apparently, those who made the decisions to withhold information and to promulgate false reports were more concerned with promoting political ends than with promoting the goal of safety – a truly central human value. Similarly false and misleading reports before, during, and after Hurricane Katrina cost lives and exaggerated the tragedy for many. These inaccurate and misleading communications undermined trust in government, in public health pronouncements, and in public health policy. When people believe that they are being deceived and that the reasons for policies are personal or political advantage rather than the public good, they are less inclined to accept the pronouncements and cooperate with the policy.

In contrast, the honest communication about the flu vaccine shortage, the clear communication about justification for the policies that governed vaccine distribution, and the efforts to communicate crucial information about distribution to the public, all contributed to cooperation with the policy and the success it achieved in avoiding deaths and serious illness. These examples highlight the need for full and honest communication and education about matters of public health and their importance in promoting justice.

Conclusion

In sum, it is difficult to achieve justice in public health policy because there is neither a single ideal governing principle nor a simple formula for success. A variety of considerations can legitimately support good policy. For public health policies to be just, the description of the situations they aim to address must be accurate and the reasons behind them must be the ones that reasonable people would find most compelling and most appropriate. Policies must reflect the choices that reasonable people would make and the priorities that reasonable people find most pressing.

Bibliography:

- Brock DW (1998) Aggregating costs and benefits. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 58: 963–968.

- Brock DW (2002) Priority to the worse off in health-care resource prioritization. In: Rhodes R, Battin MP, and Silvers A (eds.) Medicine and Social Justice: Essays on the Distribution of Health Care, pp. 362–372. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Daniels N (2002) Justice health, and health care. In: Rhodes R, Battin MP, and Silvers A (eds.) Medicine and Social Justice: Essays on the Distribution of Health Care, pp. 6–23. New York: Oxford University Press.

- DePalm A (2006) Illness persisting in 9/11 workers, big study finds. The New York Times, September 6.

- DePalm A (2007) As a way to pay victims of 9/11, insurance fund is problematic. The New York Times, February 15.

- Green RM (2001) Access to healthcare: Going beyond fair equality of opportunity. American Journal of Bioethics 1(2): 22–23.

- Kamm FM (1993) Morality, Mortality, Vol I: Death and Who to Save from It. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kamm FM (2002) Whether to discontinue nonfutile use of a scarce resource. In: Rhodes R, Battin MP, and Silvers A (eds.) Medicine and Social Justice: Essays on the Distribution of Health Care, pp. 373–389. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Rawls J (1971) A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Rawls J (1993) Political Liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Rhodes R (2001) Understanding the trusted doctor and constructing a theory of bioethics. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 22(6): 493–504.

- Scanlon TM (1998) What We Owe to Each Other. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Sheehan M and Sheehan P (2002) Justice and the social reality of health: the case of Australia. In: Rhodes R, Battin MP, and Silvers A (eds.) Medicine and Social Justice: Essays on the Distribution of Health Care, pp. 169–182. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Smith P (2002) Justice, health, and the price of poverty. In: Rhodes R, Battin MP, and Silvers A (eds.) Medicine and Social Justice: Essays on the Distribution of Health Care, pp. 301–318. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wasserman D (2002) Aggregation and the moral relevance of context in health-care decision making. In: Rhodes R, Battin MP, and Silvers A (eds.) Medicine and Social Justice: Essays on the Distribution of Health Care, ch. 5 New York: Oxford University Press.

- Aristotle (1971) The Nichochean Ethics of Aristotle, David Ross W (trans.). London: Oxford University Press.

- Bentham J (1982) An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Burns JHL, Hart HLA (eds.) London: Methuen.

- Boylan M (ed.) (2004) Public Health Policy and Ethics, Vol. 19. Amsterdam the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Brock DW (1998) Aggregating costs and benefits. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 58: 963–968.

- Daniels N and Sabin JE (1997) Limits to health care: Fair procedures, democratic deliberation, and the legitimacy problem for insurers. Philosophy and Public Affairs 26: 303–350.

- Mill JS (1979) Utilitarianism. Sher G (ed.) Indianapolis, IN: Hacket Publishiing.

- Rhodes R, Battin MP, and Silvers A (eds.) (2002) Medicine and Social Justice: Essays on the Distribution of Health Care. New York: Oxford University Press.