Sample Real Estate Development Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. What Is Development?

Real estate development is the process of adding value to real estate. While most people think of development in terms of new buildings and subdivisions, development refers to any situation where value is added to a property. Developers take ‘development risk’ which ranges from leasing-risk associated with buying buildings with high vacancy to buying raw land with no utilities or zoning, and undertaking all the risks associated with obtaining public approvals, financing, construction, leasing, and operations of a new development project.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Developers initiate, plan, and coordinate the entire development process—buying the land, designing the product, arranging financing, obtaining public approvals, constructing the building, leasing, managing, and ultimately selling the completed project. Development is distinguished from owning and managing property because it includes at least some element of adding value. While most developers also own and manage their buildings, many real estate investors and owners buy buildings that are completed and fully leased and which do not involve adding value through some form of development.

1.1 What Distinguishes Good Development From Bad?

While there is no absolute standard to distinguish good development from bad, the test is a simple one: Does the development enhance the social welfare of the community? (Peiser 1990). Providing new housing and office space enhances the community, but if it does so at the expense of environmentally precious resources, then on balance it may reduce the social welfare. Unfortunately social welfare is difficult to measure—especially the indirect costs and benefits of externalities associated with the development. Obtaining approvals for development is a political process that often is long and costly. One of the biggest challenges facing city planners and council members is to create an approval process that is unbiased and gives the various stakeholders appropriate voice in the outcome. At the same time, they must do their best to streamline the process and prevent unnecessary delays and costs.

1.2 Academic And Professional Antecedents

Real estate development relates to a number of academic fields including economics, urban planning, architecture, finance, law, political science, civil engineering, and geography. Urban economics provides the foundation for understanding real estate value and how cities change over time (Mills 1972). Real estate finance, public finance, land use, planning, and environmental law and economics, infrastructure, market analysis, demography, architecture, and landscape architecture all have significant bodies of research that contribute to our understanding of urban development and its impact on cities and countryside (see Brueggeman and Fisher 1997, DiPasquale and Wheaton 1996, Case and Shiller 1989).

Developers are generalists. They need to be conversant with many different disciplines. Because they are responsible for conceiving, planning, and executing the entire process, developers typically are strongest in finance and marketing. Because they determine what is built and how the urban landscape appears, they should be intimately familiar with cities—what works and what does not, both from a private development perspective and from a government perspective (see Garvin 1996).

Successful development requires knowledge of all of the real estate disciplines—brokerage, finance, law, political approvals, design, construction, and management. Developers usually have several years of real estate experience before they undertake their own projects, most often in brokerage or real estate finance and investment. Legal, architectural, planning, and construction backgrounds also provide excellent training.

2. Industry Structure

2.1 Ownership

The real estate development industry is an industry in transition. Historically, it consisted primarily of private entrepreneurs who operated in a single market. Today, large publicly held national companies are emerging as significant owners of property, although their role and competitive position as developers is still being defined.

The different segments of the real estate industry comprise almost 20 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (Urban Land Institute 1997). The real estate industry is composed of many different players (see Fig. 1). Developers are the entrepreneurs who create and produce real estate. They may continue to own and manage the completed buildings or they may sell them to other parties. While developers have traditionally come from the private sector in the USA, redevelopment agencies and public housing departments act as public developers, often through public– private partnerships. Many corporations and public agencies including the armed forces also develop property for their own use, which is later recycled into the inventory of space available for anyone.

Each of the players is involved in a different phase of producing or managing real estate. Developers, architects, lenders, planners, and city council workers are more involved at the front end. Owners, property managers, building departments, police and fire departments, and brokers tend to be more involved with the real estate after it is built.

Owners of property include the following:

Corporations

REITS (Real Estate Invest Trusts)

Banks—REO (Real Estate Owned)

Partnerships/Joint Ventures (JVs)

Individuals

2.2 Property Type

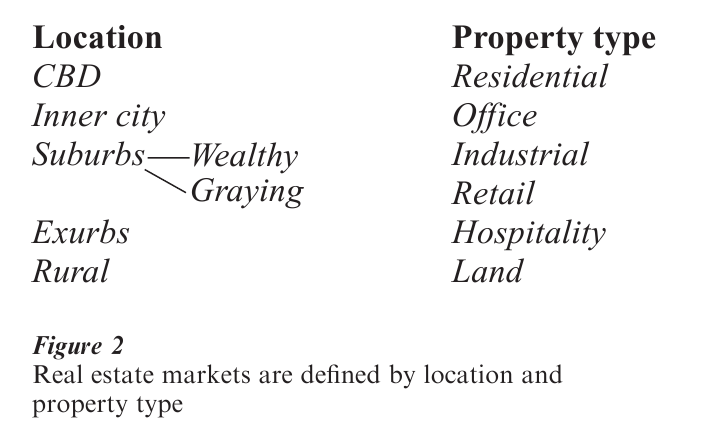

Figure 2 provides a breakdown of the real estate industry by location and property type. Each location represents a different and distinct market. All property types may be found in all locations. Certain property types, however, such as major office buildings and hotels are more likely to be developed in the Central Business District (CBD) and wealthy suburban nodes—typically located at the intersections of major freeways whereas industrial buildings, apartments, and shopping centers are more ubiquitous.

The real estate industry is divided into six main property types: residential, office, commercial, industrial, hospitality, and land (see Fig. 2). Each property type is virtually a separate industry, serving different purposes, markets, and customers. Although industrial warehouses, for example, may have completely different development requirements from apartments, they share a common institutional framework with respect to land, financing, legal aspects, and even construction. Still, each product is distinct, and value is created from different features. Apartments and industrial both benefit from locations near major highways. Industrial developers, however, prefer to avoid residential areas where homeowners complain about truck traffic. And apartment developers are attracted to areas with good schools, good retail services, recreation, and other amenities that are much less important to industrial tenants.

Developers, lenders, brokers, professional service providers, and most suppliers tend to specialize in one property type. While there is considerable cross-over between property types, such as air conditioning subcontractors who work on both office buildings and apartments, professionals develop a network of relationships over the years that favor those who concentrate on a single property type.

2.3 For-Sale vs. Income-Producing Property

A critical distinction between property types is whether they are ‘for-sale’ or are ‘income-producing.’

For-sale property Income-producing property

Land Apartments

Single-family homes Office

Condominiums Retail

Industrial

Hotels

For-sale property is sold to a buyer after it is developed whereas income-producing property is held for the cash flow it generates. For-sale property is valued based on how much buyers are willing to pay for enjoying the benefits of ownership—such as the consumption value of living in a home in a good school district near shopping and recreation.

Income-producing property includes five main property types. Values for income properties are based on the cash flow they generate from leases. Office buildings, for example, have tenants who sign 3 to 10 year leases. The developer uses the lease income to obtain long-term mortgage financing. When the office building is sold, investors pay a premium for leases signed by major corporations who have excellent credit ratings. A lease signed by a major corporation like IBM with a AAA credit rating is like purchasing a bond.

Income properties are valued by capitalizing their Net Operating Income (NOI). Capitalization rates are inversely proportional to prices. For example, if a building produces an NOI of $100,000 per year, it is worth $1.25 million on an 8 percent cap-rate ($100,000 divided by 0.08) vs. $1.0 million on a 10 percent cap- rate ($100,000 divided by 0.10). Investors may be willing to purchase a building occupied by a major corporation such as IBM using an 8 percent capitalization rate whereas they would use a much higher cap-rate, say a 10 percent, for the same property occupied by a small non-credit tenant. The rental payments of a major corporation are like a bond— carrying the same credit rating as the corporation itself. In fact, the owner can sue the corporation for lost rent if the tenant defaults on the lease payment.

2.4 Design And Density

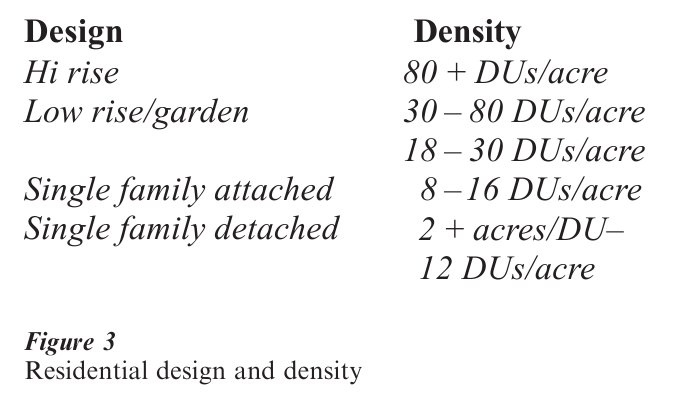

In addition to for-sale vs. income property, the development industry may be subdivided by design and density—expressed in units per acre for residential and Floor Area Ratio (FAR) for commercial buildings. Densities for residential property range from one unit/2+ acres for single-family detached homes to 80–200 units/acre for a high-rise apartment building. Residential developers tend to focus either on for-sale single-family homes or income-producing apartments. Figure 3 shows the range in densities for different types of residential construction.

3. The Development Process

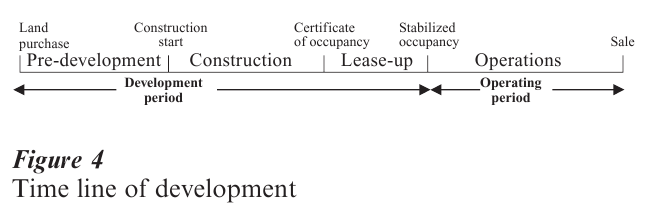

Figure 4 shows the time line of development for income-producing property. The two main periods— development and operations—involve dramatically different risks, types of financing, and activities (see Peiser 1992).

The ‘Development period’ runs from the inception of the deal through stabilized occupancy (90–95 percent occupancy). This period is financed by a construction loan, which covers the construction and lease-up of the building. The building is technically placed in operation when the ‘Certificate of occupancy’ is received. Since lease-up represents a major activity of development and risk, however, it is shown in Fig. 4 as part of the development period. The ‘operating period’ runs from the point in time when the building reaches stabilized occupancy to the time of sale. Once stabilized occupancy is achieved, the developer is able to obtain a long-term permanent mortgage which is used to pay off (‘take out’) the construction loan (see Sect. 3.5).

3.1 Stages Of Development

The development period in Fig. 4 includes predevelopment, construction, and leasing activities. The predevelopment period runs from project initiation up to the start of construction. It includes feasibility studies, site acquisition, design, and finance.

3.2 Feasibility Studies

Many of the critical development decisions are made even before a developer acquires a site. Market feasibility studies help the developer identify the best location and site characteristics for a particular development (see DiPasquale and Wheaton 1996). Market feasibility differs for each product type. It includes demographic projections, income, employment, retail sales, and growth projections. The market study should conclude with estimates of demand for the product expressed in units or square feet year in a particular location for a particular product-product type, as well as estimates of current and projected supply. The market study tells the developer how much space he can build, what rent to charge, and how quickly it can be absorbed by the market place. The market study identifies competitive properties, and helps the developer determine the best location in which to develop the product. It also tells the developer what the design features and amenities should be in order to attract the greatest number of customers.

For site selection, developers will often consider as many as 50–100 different sites in order to find five sites which they examine in detail. From the five they may pick one site to purchase. Development is said to be a local business because experienced developers will know information about most of the potential development sites, competition, rents, and costs in their market area.

3.3 Site Acquisition

Property acquisition occurs in three main stages: (a) putting the property under contract (‘opening escrow’), (b) going hard on the earnest money deposit, and (c) closing. Purchase contracts typically run from 60 to 120 days or longer. When the buyer makes an offer, he places an ‘earnest money deposit’ of 3–5 percent of the total purchase price. Purchase contracts have a number of contingencies, which the developer wants to satisfy before he consummates the purchase. ‘Closing’ is the transfer of title to the buyer and the payment of all money to the seller.

After a site is placed under contract, the developer has a 15 to 30 day contingency period to do feasibility studies. The developer will hire consultants to determine the site’s suitability for development. The analysis should cover site characteristics, environmental status, topography, drainage, utilities (water, sewer, storm, electricity, phone, gas, and cable), as well as neighboring properties, and the chance of obtaining necessary zoning and building approvals. Once the developer is satisfied that these conditions are suitable for development, he will go hard on the contract. ‘Going hard’ means that the earnest money becomes non-refundable—when the major contingencies such as good title and finding no environmental problems are satisfied. Since it may take longer than the typical 15–30 day contingency period for the developer to perform the full range of studies necessary for development, the developer will often need to ask for an extension. The developer may also do much of the investigation before the property is even placed under contract or while the purchase contract is being negotiated. In a hot market, sellers are usually unwilling to extend the contingency period because other buyers are waiting in the wings.

For a large project, the feasibility period can extend several years and cost millions of dollars before the developer receives all of the necessary approvals. In a large project, the developers almost always has to purchase the property before many of the feasibility studies are done and long before the public approvals are in place. Such projects carry full ‘entitlement’ risk and represent the most risky (and potentially the most profitable) form of development.

3.4 Design

Design includes land planning, architecture, engineering, and consulting services that go into producing completed working drawings from which the building is built. The developer will often perform considerable preliminary design work on a property even before ‘going hard’ in order to determine how much space can be built, and what it will cost based on preliminary construction bids. Design drawings are used by the developer to obtain financing and political approvals. The architect prepares working drawings after the developer approves the final design. The general contractor and the subcontractors use the working drawings to bid the project and to build it.

3.5 Finance

If developers have a distinct expertise, it is in their ability to raise equity and debt money to finance their development activities. Development financing has two main pieces—construction financing to build the project, and permanent financing for operating it. Developers obtain construction financing primarily from commercial banks. Construction loans have short terms—1–2 years—and higher interest rates— 2–3 percent above ‘prime’—than permanent mortgages. Permanent mortgages are long term—30 years, and have lower interest rates than construction loans because the completed property, especially if it has high-quality tenants, offers better security to the lender than one under construction. Historically, pension funds, insurance companies, and savings and loan associations provided most of the permanent mortgage financing, but today Wall Street is heavily involved in it through securitization, commercial mortgage-backed securities, and conduit lending. As a result, permanent financing is highly competitive in the market place and developers and owners of property have many more sources for permanent debt than they used to.

Equity financing is the most difficult and expensive money that developers raise. It represents the developer’s own cash investment in a deal, or the money raised from ‘equity investors.’ It is much riskier than debt financing because equity investors receive cash flow only after the mortgage payments are made during operations and after the debt is paid off when the property is sold.

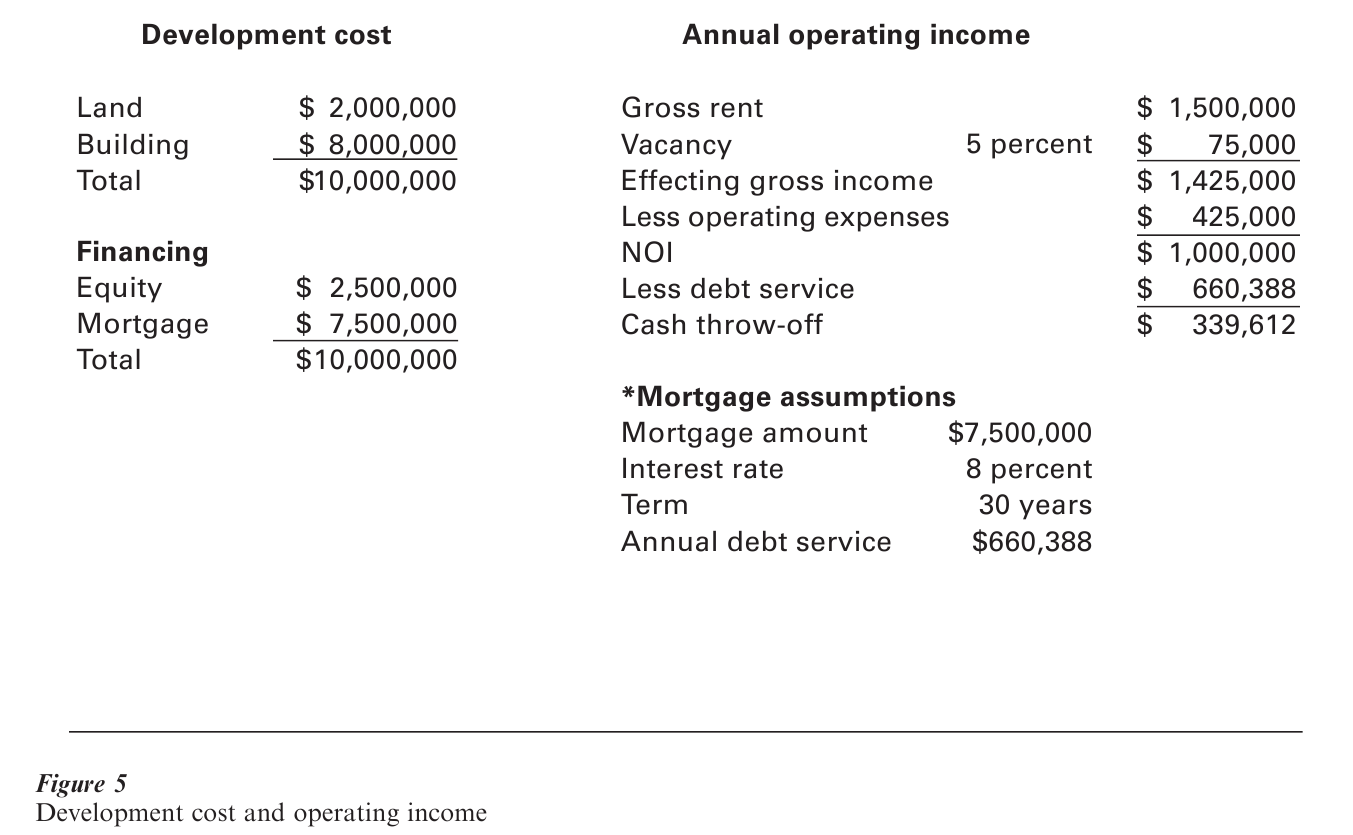

For example, if a building costs $10 million altogether, the developer would typically invest 25–30 percent cash equity and the rest would be covered by debt. Suppose the building at stabilized occupancy (90–5 percent occupancy) generates $1,000,000 in Net Operating Income (revenues minus expenses— $1,000,000 NOI divided by $10,000,000 purchase price equates to a 10 percent capitalization rate). Figure 5 shows the Development Cost, Financing, Annual Operating Income, and Mortgage assumptions for the sample building.

In Fig. 5 the simple return measures are the overall capitalization rate and the cash on cash return. The overall capitalization rate equals the NOI/Total Cost = $1,000,000 / $10,000,000 = 10 percent. The cash on cash return equals the Cash Throw Off/Equity = $339,612 / $2,500,000 = 13.58 percent.

Sophisticated investors focus on before-tax and after-tax internal rates of return (IRR) to determine whether or not they should invest in a particular real estate deal. IRRs represent annual rates of return on equity that are comparable to returns from investing in stocks or bonds. IRR requirements depend on risk. Investors require IRRs on equity that are higher than 20 percent for new properties under development whereas they may require returns as low as 10–12 percent for investing in a fully leased office building with high-quality tenants (see Brueggeman and Fisher (1997) for a detailed discussion of IRRs).

3.6 Construction

Developers hire general contractors to build most nonresidential buildings. Homebuilders and many apartment developers, however, often do their own construction. The general contractor (or homebuilder) hires subcontractors who specialize in constructing various parts of the building such as foundations, framing, glass, granite, electrical, plumbing, heating, ventilating, and air conditioning (HVAC). Legal arrangements between the developer and the contractor may take several forms depending on who bears the risk for delivering the completed building within budget and on time. Common contract arrangements include fixed price, negotiated bid, design-build, fixed-price with a savings clause (where savings are split between the general contractor and the developer), and time and materials. Larger contractors are often unionized while small contractors and especially those who work on residential projects and in certain ‘right-to-work’ states such as Texas are typically not unionized and tend to be lower cost. During the construction phase, the developer is most concerned about delivering the building on time and under budget. Since working drawings are often incomplete or have mistakes, a nonconfrontational relationship between the developer and contractor is key to success.

3.7 Leasing And Sales

Marketing for a new project begins even before the developer purchases the land. In order to obtain financing for office and retail projects, the developer often needs to demonstrate that tenants are interested in the property by obtaining letters of intent or signed leases on 30–50 percent or more of the property.

Developers may have in-house marketing personnel or use outside brokers to lease and sell their property. Exclusive brokerage arrangements are common, whereby a brokerage firm is the developer’s primary agent. Brokers work on commission which ranges from 4–6 percent of the lease or sale value for smaller deals down to 1–2 percent for larger transactions in the millions of dollars. For leasing office or warehouse space, the developer will typically pay the broker who he has hired as the exclusive agent for his property a 3–4 percent commission for signing a lease if there are no other brokers involved. The tenant often has his own broker, in which case, a higher commission will be split between the two brokers.

Successful leasing involves more than having the lowest rent for the nicest space. The developer typically gives the tenant an allowance for tenant improvements (TIs) which covers interior finish. For law offices in which tenant finish can run $70–$80 or more per square foot (compared to standard finish of $15–$25 per square foot), the TI allowance can make the difference in getting the law firm to sign a lease.

3.8 Operations

Larger developers usually have their own property management departments to handle the ongoing leasing and management of a building after it is completed. Smaller developers may hire outside firms that specialize in property management. Property management activities include repair and maintenance of the property, leasing, relations with tenants, security, building and payment of all capital and operating expenses. Good developers give careful attention to property management because it sets the tone of relations with tenants and determines their firm’s image in the marketplace.

The operating period ends with the sale of the property to a third party. Most real estate deals generate a significant part of their financial returns from appreciation in the value of the property relative to its development or purchase cost. IRRs are highly sensitive to the length of the holding period. The shorter the holding period, say 3 years or less, the higher the IRR. It is standard practice when preparing a financial proforma to assume a 7 or 10 year holding period. The actual holding period depends on the owner’s personal or institutional cash flow, tax, and life-cycle issues.

4. Current Issues

The real estate industry is highly cyclical. Because development can take from 1 to 5 or more years to complete a new project, depending on the difficulty of obtaining public approvals, buildings are often started when the market is hot, and completed when it is not. The real estate industry collapsed in the late 1980s– early 1990s in the deepest real estate recession since the Great Depression. The collapse was caused by a number of factors including over-building, tax policy that contributed to over-investment, too much careless money, and a major recession in the general economy due to downsizing of many corporations and national defense. Developers and investors who bought property at bargain prices in the early 1990s have made fortunes as rents and prices have recovered and surpassed pre-recession peaks. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, real estate markets in the USA are relatively ‘in balance’—the supply of new space is in balance with demand for new space. Cycles, however, are endemic to real estate (Grenadier 1995). Those who learn how to play them well are the ones who will be most profitable.

Sects. 4.1–4.5 detail some of the most important issues in real estate development at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

4.1 Institutionalization Of The Industry

During the recession of the late 1980s–early 1990s, many developers went bankrupt, along with the Savings and Loan Industry and many other financial institutions. Two powerful forces emerged from the recession—a vast expansion in the presence of Wall Street in real estate financing, primarily through securitization and Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities, and the re-emergence of Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) as a major owner of property (Sanders 1998). REITs grew to more than $140 billion in stock market capitalization—exceeding the 1 percent barrier of total market capitalization that represents the point at which Wall Street analysts pay serious attention to an industry. While REITs and other publicly financed companies, especially national homebuilders, will play a more important role in real estate development and ownership than before, entrepreneurial developers will continue to play a significant if less dominant role in the creation of new product.

4.2 Future Of Cities

Central Business Districts and inner-ring suburbs have gone through ups and downs over the last 50 years as many companies and higher-income residents have moved to outer-ring suburbs and smaller towns at the urban fringe. The constant outward migration has created enormous expansion of rapidly growing cities such as Atlanta, Phoenix, Dallas, Denver, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle. The outward growth has put pressure on open space and natural resources and placed demand on the public sector to build highways and other infrastructure to serve the new development.

At the same time, central cities and inner suburbs have suffered under declining municipal tax revenues and increasing demands for services from a poorer population, often augmented by new immigrants. While many cities such as Manhattan and Los Angeles are seeing signs of a return to the CBD by investors and residents, outward migration is likely to continue. Urban containment boundaries are a popular though controversial, technique for containing outward expansion. Developers have historically tended to prefer green-field suburban sites because they are easier to build, easier to finance, and more attractive to tenants and homeowners. Whether central cities and inner suburbs will be able to attract new investment and redevelopment is one of their most important challenges.

4.3 Smart Growth Urban Sprawl

The rapid expansion of suburban growth in the last half of the twentieth century has fueled a backlash against development and NIMBYism (not in my backyard). ‘Smart growth’ is the latest approach to solving the problems associated with urban sprawl— congestion, loss of farmland, lack of functional open space, monotonous and boring development, and inadequate infrastructure (see Gordon et al. 1989, Peiser 1989).

4.4 Public–Private Development

As the regulatory process for major development projects has become more time consuming and costly, more developers are joining forces with cities, redevelopment agencies, school districts, armed forces, and other government agencies to develop property. The public–private partnerships help developers to obtain lower cost financing and necessary public approvals while giving public agencies a share in the profits and the ability to deliver more public benefits such as parks, plazas, roads, sewer plants, and other infrastructure (Kotin and Peiser 1997).

4.5 Technology

The internet and other new technologies are having dramatic impacts on all aspects of real estate, from office building construction to shopping center functionality resulting from Internet commerce. As old shopping centers and industrial buildings become obsolete faster, new industrial distribution centers and ‘entertainment’ shopping centers are replacing them. While home offices and telecommuting have caused alarm for future office space demand and spawned new work patterns such as ‘hot desks’ (where employees share office space, plugging their lap top into the company computer network as they move from office to office) workers still appear to want the ‘social’ aspects of coming to work. Suburban corporate campuses with high tech communications, on-site recreation and sporting facilities, and high security are being built to respond to new workplace needs and employee preferences.

5. Social Responsibility

Real estate development touches on every aspect of people’s lives. It determines not only the quality of the built-form environment, but also affects the life-style and social wellbeing of residents and workers in every community. What developers build may last a lifetime or longer. Because of their far-reaching role, developers bear a special responsibility. Most developers care deeply about the quality of their projects. High quality development depends as much on public sector support and services as it does on the private activities and financial resources of the developer. Since real estate involves very long-term investment, the long-term stability of the community and continuing attractiveness to new residents and firms is essential to long-term profitability for the developer. While developers are often vilified for destroying the environment and hastening neighborhood change, good development is responsive to neighborhood concerns and is sensitive to maintaining and improving environmental conditions. As public funds have been reduced for open space infrastructure improvements, development is often the instrument through which open space is preserved and new infrastructure is built. As their role expands, developers need to be ever more knowledgeable about the urban context in which they build and about the multitude of forces with which they must deal. The Urban Land Institute’s mission statement sums up the developer’s charge: ‘to provide responsible leadership in the use of land in order to enhance the total environment.’

Bibliography:

- Brueggeman W, Fisher J 1997 Real Estate Finance and Investments. Irwin McGraw-Hill, New York

- Case K E, Shiller, R J 1989 The efficiency of the market for single-family homes. American Economic Review 79: 125–37

- Corgel J, Smith H C, Ling D 1998 Real Estate Perspectives. Irwin McGraw-Hill, New York

- DiPasquale D, Wheaton W 1996 Economics and Real Estate Markets. Prentice Hall, London

- Garvin A 1996 The American City: What Works, What Doesn’t. McGraw-Hill, New York

- Gordon P, Kumar A, Richardson H 1989 Influence of metropolitan structure on commuting time. Journal of Urban Economics 26(2): 138–51

- Grenadier S R 1995 The persistence of real estate cycles. Journal of Real Estate Finance & Economics 10(2): 95 –119

- Kotin A, Peiser R 1997 Public-private joint ventures for high volume retailers: who benefits? Urban Studies 34(12): 1971–86

- Mills E S 1972 Studies in the Structure of the Urban Economy, Resources for the Future. The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore

- Peiser R 1989 Density and urban sprawl. Land Economics 65(3): 194–204

- Peiser R 1990 Who plans America: Planners or developers? Journal of the American Planning Association Autumn: 496–503

- Peiser R 1992 Professional Real Estate Development: The ULI Guide to the Business. The Urban Land Institute, Washington, DC and Dearborn, Chicago

- Sanders A B 1998 The historical behavior of REIT returns: A capital markets perspective. Garrigan R T, Parsons F C (eds.) Real Estate Investment Trusts. pp. 277–305

- Urban Land Institute 1997 America’s Real Estate. Washington, DC