Sample Psychology Of Entrepreneurship Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, chech our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Small and medium sized enterprises are important for the economy because they are the major agents of economic growth and employment (about 99 percent of the European companies are small or medium sized and they provide 66 percent of the working places, European Council for Small Business newsletter, 1997). They add jobs faster than bigger companies in the developed and underdeveloped world. Small-scale firms are highly adaptable and able to act quickly and innovatively.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Psychological approaches to entrepreneurship have experienced a revitalization recently because of the future importance of small-scale entrepreneurs and because the entrepreneur is at the boundary line of individual work psychology (personality, work activities, etc.), organizational psychology (founders of the organization have an enormous influence on it), and market psychology (economic activities in the market). Many organizational issues, for example, the influence of human resource practice, can also be studied in entrepreneurs. Essentially, all aspects of psychology are implicated when studying entrepreneurs (Rauch and Frese 2000).

Relevant literature in this area is distributed in many outlets and can be found in such diverse journals as the Journal of Applied Psychology, Academy of Management Journal and Review, Administrative Science Quarterly, Journal of Small Business Management, Journal of Business Venturing, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Journal of Management, Small Business Economics, World Development, Strategic Management Journal, Organization Studies, and there are many articles in conference procedures such as Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, and International Council of Small Business Conference Proceedings.

1. A General Psychological Model Of Entrepreneurial Success

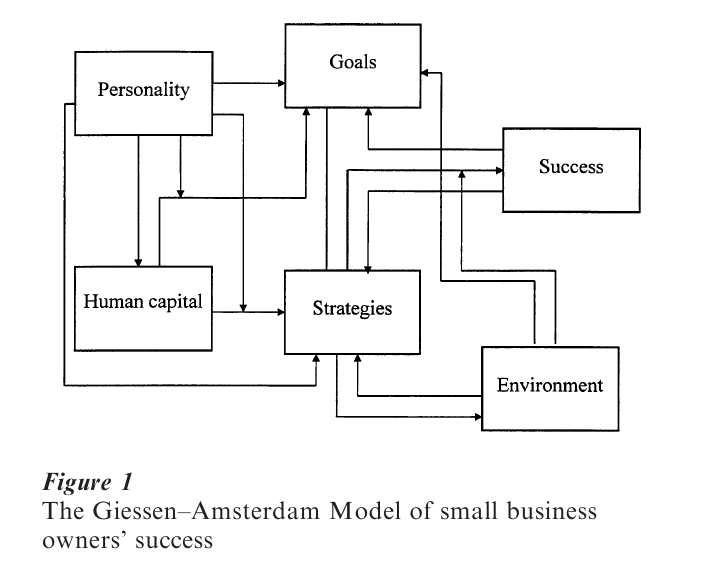

Figure 1 presents a general psychological model of entrepreneurial success. It helps us to organize this contribution, and also has some controversial implications. For example, it does not hypothesize any direct links from personality, human capital, or environment to success because we assume that there is no success without actions. Actions are mainly determined by goals and strategies. Therefore, according to this model, psychological strategies of actions are the bottleneck through which all of entrepreneurial success is accomplished or not accomplished. The model can also be used to understand the different levels of analysis: one can differentiate the organizational level and the individual level of the firm owner with regard to each issue in Fig. 1. The level of analysis issue has a slightly different meaning in the area of entrepreneurship because company size determines which level is the adequate one. In large companies, the right level of analysis is the organizational level, in small firms, the firm owner is typically the source of action of this firm. When there are only four or five employees in a firm, the owner usually has a much stronger impact on company policy, company culture, and the company’s actions than in larger firms and an individual level of analysis can be used profitably for these firms.

2. Definition Issues: Entrepreneurs, Business Owners, And Other Concepts

There is no agreed-upon definition of entrepreneurship. Moreover, founders and owner managers are a highly heterogeneous group that defies a common definition. Probably the best strategy is to use a behavioral definition because it does not make any further assumptions of success, growth, or failure (e.g., Hisrich 1990): entrepreneurship is the study of founders/managers of organizations. However, one should also be open to the fact that there is a growing interest in entrepreneurship within large organizations.

3. Characteristics Of The Entrepreneur

It is necessary to separate the emergence and the success of entrepreneurs. There may be different processes by which a person decides to become an entrepreneur and by which a person achieves entrepreneurial success (Utsch et al. 1999). Personality characteristics may be more important for the decision to become a founder than for success.

3.1 Personality And Emergence Of Entrepreneurship

McClelland’s (McClelland and Winter 1971) early work suggested that need for achievement should be higher in people who start a business. This is indeed the case as a quantitative review shows (Rauch and Frese 2000). A similar result appears for locus of control (Rotter 1966). Business owners have a slightly higher internal locus of control than other populations (Rauch and Frese 2000). Other studies have found a high degree of innovativeness, competitive aggressiveness, and autonomy (Utsch et al. 1999), Protestant work ethic beliefs (Bonnett and Furnham 1991), or risk taking (Begley and Boyd 1987). The literature about the emergence of entrepreneurship highlights that entrepreneurs are different from managers and other groups.

More recently, researchers developed more sophisticated personality concepts that match the personality variables with the behavioral requirements of an entrepreneur, for example, the Entrepreneurial Attitude Scale (EAO), which consists of achievement, self-esteem, personal control, and innovation (Robinson et al. 1991) or task motivation theory (Miner et al. 1994).

3.2 Personality And Success

The most frequently studied personality characteristics were need for achievement, internal locus of control, and risk-taking. A quantitative review showed a weighted uncorrected mean correlation of 0.13 between need for achievement and success. It is important to note that there is a reduced variance in these samples because of the fact that emergence is also related to the achievement motive (Rauch and Frese 2000). Studies showed that achievement motive could be enhanced and that this leads to a higher success in business (e.g., McClelland and Winter 1971). A similar relationship with success also appeared for locus of control (Rauch and Frese 2000). In contrast, high risk-taking is not or even negatively associated with business success (Rauch and Frese 2000).

3.3 Personality Reconsidered

Thus, there are differences between entrepreneurs and managers, and correlations between personality and success, but these correlations are not high. It is, therefore, understandable that criticisms of a personality approach have appeared.

However, both approaches—the personality proponents and its critiques—have overlooked the significant advances that have been made in personality research during the last 20 years that need to be made useful for entrepreneurship research. The most important issue is certainly that specific behaviors (such as starting up a business or using a certain approach to the market) works only through mediating processes (cf. the Giessen–Amsterdam model in Fig. 1). For example, planning mediated the relationship between achievement orientations and success.

Second, the personality variable has to be specific enough to predict specific (entrepreneurial) behavior. For example, Miner et al.’s (1994) task motivation theory explained 15–24 percent of variance in growth measures.

Third, interaction models suggest that one looks at which personality trait helps in which environment. Thus, one would have to look at interactions of personality with environmental conditions.

Finally, no one personality trait will ever have a strong relationship with success because success is determined by many factors.

4. Human Capital

Human capital theory is concerned with knowledge and experiences of small-scale business owners. The general assumption is that the human capital of the founder improves small firms’ chances of survival (Bruederl et al. 1992). Human capital acts as a resource. However, human capital theory studies usually assume that experiences are translated into knowledge and skills. This assumption is problematic, however, because length of experience is not necessarily a good predictor of expertise (Sonnentag 1995). Therefore, it is not surprising that human capital factors, such as length of managerial or industry experiences or education, are not strong predictors of success, although in large-scale studies they usually are significant (Bruederl et al. 1992, Rauch and Frese 2000).

5. Goals

One can distinguish between goals related to the startup of an enterprise and goals related to the existing enterprise. Goals or motives for becoming self-employed can be categorized into push and pull factors. Push factors imply that a current situation (e.g., the job or unemployment) is unsatisfying, pull factors are related to desires for being independent and doing what one likes to do. While there are differences among entrepreneurs, there is little evidence that goals related to developing a business are related to success (Frese 2000).

6. Strategies (Content, Process, Entrepreneurial Orientations)

From a psychological perspective strategies are directly related to goal-oriented actions. It is useful to distinguish between three dimensions of business strategy: content, process, and/or ientation. All three strategy dimensions can in principle be crossed with another.

First, strategic content is concerned with the type of business decisions vis-a-vis the customers, suppliers, employees, products, production factors, marketing, capital, competitors. Studies in this area are often done by economists although psychological issues are important as well, for example, how to convince banks to give credit, active strategies on the market, for example in developing a niche product, and so forth.

Second, the strategic process is concerned with formulation and implementation of strategic decisions (Olson and Bokor 1995). One issue is planning, which is related to success (Schwenk and Shrader 1993). Frese and his co-workers (Frese 2000) have recently presented a theoretical typology of psychological strategies that are differentiated along the dimensions of proactivity and planning. Planning strategy implies that a top-down planning process is used that is also highly proactive. Critical point planning implies that an important issue is planned but other issues are not. It is proactive and involves a smaller amount of planning. Opportunistic strategy implies very little planning but a high degree of proactivity: one looks out for opportunities and takes them without any detailed planning beforehand. Finally, the reactive strategy implies that one is neither proactive nor planning: one simply reacts to the demands of the situation. The latter is negatively correlated with success in various countries (four African countries), while all others are positively correlated with success (Frese 2000); however, the relationship between planning and success depends on the situation to a certain extent. A Dutch longitudinal study has also shown that there is a reciprocal determinism from a reactive strategy to failure and from failure to reactive strategy (Van Gelderen and Frese 1998).

Third, orientation implies an attitude towards one’s strategy: why a strategy is played out. Lumpkin and Dess (1996) conceptualized entrepreneurial orientation to consist of five dimensions: innovation, proactiveness, risk-taking, autonomy, and competitive aggressiveness. Covin and Slevin (1986) showed among others that entrepreneurial orientation was highly related with company performance (r=0.39, p<0.01). The relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and success may also be contingent on environmental and/or ganizational factors.

7. Environmental Conditions

Each enterprise is nested in a specific environment. The task environment can be divided into three bipolar dimensions: complexity, dynamism, and munificence. Complexity describes the homogeneity versus heterogeneity of an environment. In a complex environment it is more difficult to get and to consider all the necessary information than in an easy environment. Dynamism describes the variability and unpredictability of the environment. Munificence falls into two subconcepts: ease of getting customers and ease of getting capital.

Sharfman and Dean (1991) showed that munificence had no significant relationship with performance, but complexity and dynamism were positively related to success. Thus, an unfavorable environment—the dynamic environment—has positive consequences. According to Swaminathan (1996), organizations founded in adverse environments have a higher initial mortality rate. But beyond a certain age, the surviving organizations had a lower mortality rate than those founded in a more friendly environment.

8. Other Issues Of Psychological Entrepreneurship Research

There are other psychological issues that have not been studied as much as the ones discussed above but that are potentially interesting (see Rauch and Frese 2000). Among them are the effects of networks, information search activities to get feedback, and/or ganizational life cycle models. Moreover, there are leadership issues and one can study whether visionary leadership, communication, delegating, and performance facilitation are related to success. Social psychological and cognitive factors are most likely related to entrepreneurial outcomes, such as values and culture, attributional theory, and problem-solving styles. Other issues of this type are concerned with learning, minorities, human resource management, learning and training, feedback processing, transition from business founder to manager, financing, organizational culture, and others. One fascinating topic is the issue of making psychological entrepreneurship research useful for developing countries.

9. Conclusion

Psychological approaches to entrepreneurship are fascinating both for entrepreneurship and psychology. Entrepreneurship can profit from this interface between business and psychology because psychological variables are clearly related to entrepreneurial entry and success. Psychological variables (most notably action-related concepts) function as mediators in the process that leads to success (e.g., strategies). For psychology, entrepreneurship is interesting because it combines the following features.

(a) The level of analysis question is related to the dynamic of enterprise growth; in the beginning, a small scale enterprise is best described by looking at the owner. However, in somewhat more mature enterprises, the level of analysis has to change because more delegation, management, and implementation are necessary.

(b) Some interesting organizational hypotheses can better be studied with small-scale entrepreneurs than with large organizations. A good example is the study of contingency theories. Small-scale enterprises are more coherent than larger ones and, therefore, contingency models can be tested better.

(c) Even large organization attempt to mimic small enterprises, and stress intrapreneurship, innovation, and personal initiative. There is no doubt that future workplaces will stress innovation and personal initiative more strongly and we need to know how small-scale entrepreneurs act.

(d) Interdisciplinary cross-fertilization takes place in this area.

We have reported a number of different models in this review; they are often presented to be contradictory. For example, some people have pitted personality approaches against human capital approaches. As Fig. 1 shows, we assume that they coexist and can influence each other (e.g., IQ has an influence on the development of skills and knowledge). An integration of various approaches to make real headway towards understanding a societally important phenomenon—entrepreneurship—is called for and should produce challenging research.

Bibliography:

- Begley T M, Boyd D B 1987 Psychological characteristics associated with performance in entrepreneurial firms and small businesses. Journal of Business Venturing 2: 79–93

- Bonnett C, Furnham A 1991 Who wants to be an entrepreneur? A study of adolescents interested in a Young Enterprise scheme. Journal of Economic Psychology 12: 465–78

- Bruederl J, Preisendoerfer P, Ziegler R 1992 Survival chances of newly founded business organizations. American Sociological Review 57: 227–42

- Covin J G, Slevin D P 1986 The development and testing of an organizational-level entrepreneurship scale. In: Ronstadt R, Hornaday J A, Peterson R, Vesper K H (eds.) Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. Babson College, Wellesley, MA, pp. 628–39

- Frese M (ed.) 2000 Success and Failure of Microbusiness Owners in Africa: A Psychological Approach. Greenwood, Westport, CT

- Hisrich R D 1990 Entrepreneurship Intrapreneurship. American Psychologist 45(2): 209–22

- Lumpkin G T, Dess G D 1996 Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review 21(1): 135–72

- McClelland D C, Winter D G 1971 Motivating Economic Achievement. Free Press, New York

- Miner J B, Smith N R, Bracker J S 1994 Role of entrepreneurial task motivation in the growth of technologically innovative firms. Interpretations from follow-up data. Journal of Applied Psychology 79(4): 627–30

- Olson P D, Bokor D W 1995 Strategy process–content interaction: Effects on growth performance in small, start up firms. Journal of Small Business Management 27(1): 34–44

- Rauch A, Frese M 2000 Psychological approaches to entrepreneurial success: A general model and an overview of findings. In: Cooper C L, Robertson I T (eds.) International Review of Industrial and/or ganizational Psychology, 2000. Wiley, Chichester, UK, pp. 101–41

- Robinson P B, Stimpson D V, Huefner J C, Hunt H K 1991 An attitude approach to the prediction of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 2: 13–31

- Rotter J B 1966 Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs 609(80): 1

- Schwenk C R, Shrader C B 1993 Effects of formal strategic planning on financial performance in small firms: A meta-analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 17: 48–53

- Sharfman M P, Dean J W 1991 Conceptualizing and measuring the organizational environment: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Management 17(4): 681–700

- Sonnentag S 1995 Excellent software professionals: Experience, work activities, and perceptions by peers. Behaviour & Information Technology 14: 289–99

- Swaminathan A 1996 Environmental conditions at founding and/or ganizational mortality: A trial-by-fire model. Academy of Management Journal 39(5): 1350–77

- Utsch A, Rauch A, Rothfuss R, Frese M 1999 Who becomes a small scale entrepreneur in a post-socialist environment: On the differences between entrepreneurs and managers in East Germany. Journal of Small Business Management 37(3): 31–41

- Van Gelderen M, Frese M 1998 Strategy process as a characteristic of small scale business owners: Relationships with success in a longitudinal study. In: Reynolds P D, Bygrave W D, Carter N M, Manigart S, Mason C M, Meyer G D, Shaver K G (eds.) Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. Babson College, Babson Park, MS, pp. 234–48