View sample Environmental Strategy, Leadership, and Change Management Research Paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a management research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The past 40 years of business and the environment in the United States has been dominated by legal and regulatory action and the end-of-the-pipe, technically based solutions to these issues. Until recently, firms that did create specific environmental functions within the organization rarely engaged these staff members on issues of strategic importance. Instead, the environmental department was placed in a position of little authority and power, existing as a bag on the side of the corporate hierarchy, where the core business functions reside. Their position and authority rarely offered the potential for lending value to the firm; more often, they were viewed as a cost center by upper management.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

As the response to environmental pressures and demands evolved, firms began to see the strategic potential of environmental management—leading managers to the recognition of cost avoidance through pollution-prevention initiatives, and later, the opportunities present in linking environmental performance to core products and services. Many businesses now make decisions that include “beyond compliance” elements of environmental management— that is, public demand, image and reputation, new product development, and environmentally related new-business opportunities.

When businesses’ responses to environmentalism have been tied to core business decisions, however, a great deal of organizational change has been required—including overcoming the “Green Wall” between early treatment of environmental issues and the language, tools, and culture of business. This Green Wall, a term first coined and popularized in the mid-1990s by the consulting firm Arthur D. Little, centers on the concept that the tools used to measure, manage, and lead change in business are not the tools used traditionally by the environmental functions in business. In the case of managing environmental issues by organizations, corporate leaders have been driven to evolve over time from early industrial, regulatory, and social responsibility foci toward a mindset of the natural environment as strategic in nature. This recognition is increasingly important, especially with the rise of broader sustainable development and corporate social responsibility concerns. One survey of over 400 senior executives from Fortune 500 companies revealed that 92% of these business leaders believe the environmental challenge will be one of the central issues of the 21st century (Berry & Rondinelli, 1998). Clearly, environmental management and strategy has reached the executive level in many larger businesses, yet often the Green Wall remains a deeply rooted cultural obstacle in organizations, especially in the United States.

Management research on the business and the natural environment has focused on such topics as the description of environmental issues for business, environmental strategy and decision making, environmental accounting and measurement, the content and effects of laws and standards on business, the links between environmental and economic performance, and the relevance of external stakeholder pressure and public disclosure. More recently, the focus of research in environmental management has been on the role the natural environment plays for business decision making in an even broader sense—specifically, sustainability and corporate social responsibility.

In most cases, the question has been what firms are doing, rather than how or why they are making the changes required for organization-wide action on environmental issues. Where research has discussed the hows of the change process, that discussion has been most often covered by changes in products, systems, specific confined initiatives, and leadership commitment, not organization wide changes. In cases where research has touched on organizational change and corporate environmental behavior, the focus has been on integrating environmental management throughout departments. More so, research on the motivations or drivers for business behavior connected to the natural environment predominantly focuses on moral-ethical, cognitive, coercive-regulatory, competitive, and socially responsible drivers for change. As such, it pays to look at each of these drivers and how they relate to organization-wide change.

Early Moral Drivers Of Corporate Environmentalism

In order to explore the evolution of the business communities’ response to the age of environmentalism—as expressed through environmental crisis, public pressure, the formation of environmental laws, and evolving competitive demands—it is relevant to look at not only the internal elements of business organizations (i.e., structure, staff, and culture changes), but also the external pressures that have shaped corporate environmentalism (i.e., environmental events, regulatory constraints, and public demands). Just as technology changes, demographic shifts, and the internationalization of business serve as the dynamic backdrop to corporate decisions of price, distribution, and service in the United States, so too has the age of environmentalism, since the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 affected business decisions, performance, and ultimately, competitive success. In a very general way, environmental management has seeped into nearly every aspect of business decision making and operations for large and increasingly for small firms as well. From consumer boycotts and demands of environmental consumers to the regulatory and legal environment reflected in the state and federal statutes, a wide array of environmental interests must be managed in today’s business operating environment.

The early environmental movement and the following decades painted a moral-ethical picture of the evil corporate interests against nature itself (as represented by environmental organizations and government policy). This good-versus-evil representation has had a strong impact on the behavior of stakeholders within business and outside. Thus, much of the early change efforts from the private sector came from those companies whose mission held core values for the environment from the start. In this case, environmental stewardship throughout business practices was simply the right thing to do. Even today, when environmental leaders within industries (i.e., firms participating in voluntary environmental programs [VEPs]) are surveyed, “the right thing to do” is the most often cited reason for their corporate commitment to the environment.

Yet, a full understanding of the influence that the environmental movement has had on modern business decision making requires an understanding of history. Although concern for the natural environment had been expressed in word and deed well before the 1960s, this decade signaled the first time that business activity was directly tied to environmental degradation in a public manner. The conservation movement of the late 1800s and 1900s reflects a long-standing recognition in the United States of man’s impact and impingement on the natural environment.

The Changing Legal Environment

American environmental regulatory policy came as a wave of change crashing on the shores of the public and private sectors alike during the 1960s. Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring, published in 1962, ignited the public and helped spark this new environmental movement. During this decade, Lake Erie was declared dead, the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland caught fire and burned for five days, the nation’s proud symbol, the bald eagle, was near extinction from DDT poisoning, and smog in some U.S. cities was often visible and noxious. As a result, public outcry for federal leadership in protecting the country’s natural environment and public health took a strong hold of Washington, as well as other state capitals, in the form of legal mandates and regulatory requirements.

While human activity was seen as responsible for environmental damage before the 1960s, it wasn’t until Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring that the public, and eventually political leaders, saw American industry and the products of industrial technology as directly responsible for biotic damage. Nature was seen as finite and fragile. The resultant public outcry—a critical mass of public opinion energizing the first Earth Day, the subsequent creation of the EPA, and the snowballing federal regulations in response to public demands—created an additional constraining force on private-sector action throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and into the 1990s. The exponential growth of these new legal requirements for business was coupled by an expansion of stakeholder expectations, that is, the expectations of investors, consumers, and environmental groups.

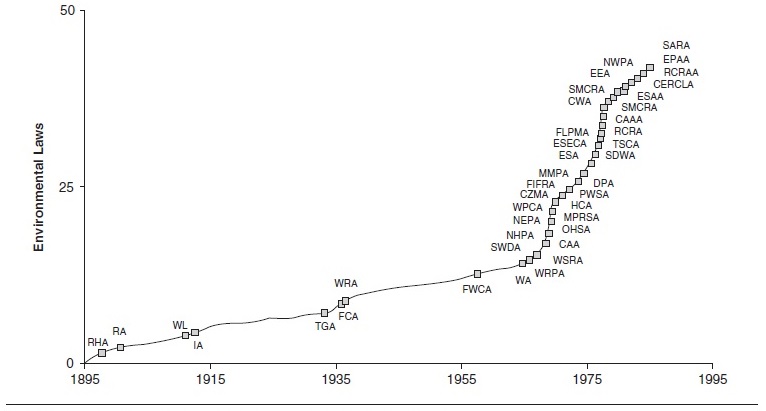

Figure 1 Exponential Growth of U.S. Laws on Environmental Protection

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sprang from President Nixon’s Blue Ribbon Presidential Council on Government Reorganization. Nixon had proposed the development of a Department of Natural Resources and Environment to address issues concerning natural resources, pollution control, public lands, and energy. During the 1960s within the federal government, environmentally related responsibilities were divided among 20 agencies receiving funding from 24 different Congressional committees. Nixon’s reorganization was an attempt to streamline these efforts as much as possible. It was an early attempt to reinvent government and America’s environmental policy. Eleven months after the National Environmental Policy Act was enacted, Nixon established the EPA as the federal government’s second exclusively directed environmental body—formed from the merger of the Department of Interior, Health, and Environmental Welfare with smaller pieces from other federal agencies.

As a result of the federal restructuring over the next 2.5 decades, the role of the EPA as the country’s regulatory agency on the environment expanded. The American environmental movement, public pressure and opinion, and advocacy-group influence pushed Congress toward the enactment of laws protecting the environment. The speed and amount of statutory requirements—primarily directed towards the private-sector producers—was astonishing (see Figure 1).

The bulk of the statutory requirements and regulation developed over that long period were command-and control and end-of-the-pipe in nature, and directed at large, manufacturing operations and heavy industries. Congress set statutory guidelines, and the EPA created specific requirements under the law addressing issues such as Best Available Control Technologies (BACT) for air and water protection, maximum permissible amounts of pollution, toxicity contents, and so forth. As such, although other agencies in the federal government have environmental responsibilities (i.e., Interior, Defense, Energy), the EPA is the primary pollution-control agency. Media specific in nature (i.e., air, water, and land), the country’s environmental public policy evolved in an adversarial fashion—with EPA lacking trust in the private sector’s commitment and willingness to protect the environment, and firms, in turn, criticizing EPA’s less-than-common-sense approaches to environmental protection. The often ad hoc approach to environmental protection, initially at the root of EPA itself, was a result of the Agency’s need to react to congressionally mandated statutory requirements. These statutory requirements looked to address environmental protection and pollution issues but in a rather piecemeal and media-specific fashion.

The corporate response to the expansive legal framework throughout the first 2 decades often relied upon denial, and of course, legal retaliation, and sometimes, grudging acceptance. Most of the money spent on environmentally related business functions throughout the 1970s and 1980s focused on the prescriptive, end-of-the-pipe technology requirement (i.e., capital expenditures on smokestack scrubbers, wastewater treatment systems, etc.), lobbying efforts against impending legal requirement, and the legal fees tied to the inevitable court battles in opposition to these new environmental requirements.

Corporate Environmental Management Evolves

The historical response to environmental management pressures by larger firms varies only slightly among researchers. Early regulatory pressure fundamentally shaped organizational behavior, with social responsibility models, and eventually, business opportunity models of corporate environmentalism later shaping business behavior toward the natural environment. This directly affected organizational structure as well for larger firms.

In the 1970s, many larger firms in the United States had dedicated environmental staff functions, mostly as part of an environmental, health, and safety department. During the 1980s, this trend of building internal environmental affairs and management capabilities continued. A clear expansion of staffing occurred. Multinational corporations created a whole infrastructure of units at different levels—corporate, division, and facility—as well as coordinating functions. In addition, many of them created positions of vice presidents for environmental affairs. With this, a new leadership position was born in corporate structures—the chief environmental officer.

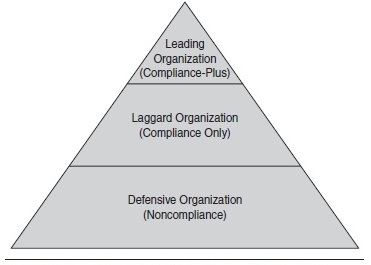

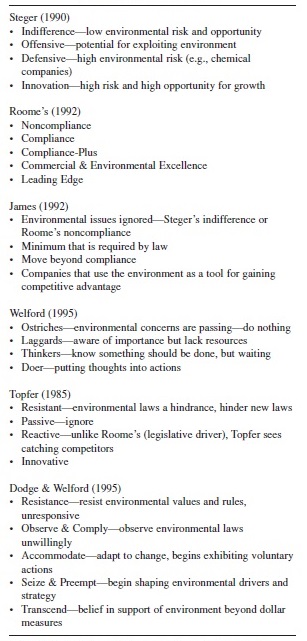

Research has identified the stages that businesses have gone through due to these evolving public and legal pressures and resultant attempts to make environmental performance a point of competitive advantage (see Figure 2 and Table 1). In each of these cases, the institutional inertia of regulatory-driven business environmentalism is heavy and hard to overcome.

Figure 2 Dominant Types of Business Responses to Environmental Pressures

In the wake of the regulatory barrage of the 70s and 80s, larger firms like Dupont, Dow, and Xerox began to look for ways to bypass their competition and anticipate change. This signaled the birth of corporate environmental strategy. With this new view, corporate decision makers began to recognize the opportunities inherent in identifying environmental customers, managing suppliers, seeking statutory-driven business opportunities, filling new environmental product niches, improving process efficiency, and finding real potential for enhanced public image for environmental and social responsiveness. Yet, the sheer number and reach of these leading firms has remained, up until the past decade, limited.

Table 1 Phases of Business Behavior on the Natural Environment: Early Literature

Forest Reinhardt presented a summary of research on environmental strategy, identifying five dominant environmental business strategies: (a) environmental product differentiation, (b) managing competition through environmental strategy, (c) reducing costs, (d) redefining markets, and (e) managing risk and uncertainty. With each of these strategies, varying degrees and types of integration between environmental knowledge, staff, and assessment and business thinking are needed. Yet, from Wal-Mart to General Electric, many leading corporations are continuing to find the business value of environmental strategy.

Like the evolution of environmental regulation, the actions and interests of the press and media, interest groups, and the external manifestation of crisis management have also shaped corporate environmental strategy. An examination of broader management of social and political issues and the institutional response by larger firms to press coverage and interest group pressure shows that firms adopted external scanning mechanisms, environmental communications departments, and long-range strategies as a result of these nonmarket pressures as well. Leading firms have come to manage threats and opportunities related to the natural environment in a way that includes public perception.

Market studies in the United States have also indicated that consumers can be drivers for environmental-preferable products and can be segmented into specific categories based on environmentally related product-purchasing tendencies, specifically (Roper Starch/S. C. Johnson & Son, Inc. 1993)

- 10-15% are True-Blue Greens—very committed to the environment and will pay more for an environmentally preferable product or service;

- 10% are Greenback Greens—also committed to the environment, but not as likely to pay more for a specific environmental product;

- 50-55% are Half-Greens—express concern, but act erratically as a buyer, occasionally taking environmental performance into consideration of buying decisions; and

- 30% are Basic Browns—either too poor to focus on environmental issues as a buyer or simply do not care about the environment.

The leading segments of customers have served to spur a green-consumer movement in the United States—something that evolved years before in places like Europe. This factor is increasingly important to corporate strategists in the age of global competition. When environmental performance is wrapped together with corporate citizenship and measures of sustainability (including economic, environmental, and social-management issues) for companies, the landscape for success in business becomes murky, untested, and frightening. Yet, this growing segment of green consumers is also driving the need for businesses of all types to better integrate environmental concerns in day-to-day operations.

More recent studies report that the market for green products and services is nearly $440 billion, or 4.3% of the U.S. economy, and is expanding twice as fast as the gross domestic product. Likewise, socially responsible investing now tops $2 trillion and 70% of Americans surveyed reported that a company’s commitment to social issues is an important element in their investment decisions.

Other external facets that have been driving behavior on the natural environment for larger firms include the following:

- Banks are faster to lend to companies that prevent pollution and avoid risk.

- Insurance companies are more eager to underwrite clean companies and see environmental leadership as a signal of a well managed (i.e., less risky) company.

- Employees want to work for environmentally responsible companies, especially as an increasing number of younger employees enter the workforce. This trend will only continue as more baby boomers reach retirement age.

- Clean companies are rewarded with relief from green taxes and charges; over time this may evolve into rewards for carbon neutrality as global warming continues to evolve as a business topic.

Sustainability And Social Responsibility

Recently, environmental management has grown to be included as an element of the broader sustainable development and corporate social responsibility literature. The commonly accepted definition of sustainable development or sustainability is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. This definition has incredible potential impact on businesses with respect to resource use of raw materials, pollution, waste from production processes that could irreparably harm the ecology for future generations, and even the nature of the workforce and issues like social justice and social equity.

Yet, businesses are coming to embrace the concept of sustainable development and its impact on business decision making. In a PricewaterhouseCoopers’ survey of 150 U.S.-based chief financial officers and managing directors for Fortune 500 firms, 81% reported that sustainability practices would be essential or very important to their company’s strategic mission over the next two years. As markets become increasingly closer globally, multinationals will be the first to wrestle with the transboundary, intergovernmental, and socially rich matrix of sustainability. While the recognition of its importance is seen at the top level, the integration of both environmental and societal considerations through organizations will only complicate the Green Wall phenomenon.

A central issue to sustainability research is if and how to harness the enormous power of the private sector to serve all of society. Researchers and business leaders alike believe that this can only happen through multi-stakeholder

partnerships between businesses, NGOs, communities, and governments to develop collaborative sustainable business models that are ecologically responsible, socially just, and inclusive for all. Emerging research perspectives on corporate sustainability acknowledge that businesses can play a fundamental role in achieving social objectives, but that in practice this requires an understanding of multistakeholder collaboration and partnering, resulting in new capabilities as a result of those partnerships, which challenge traditional business assumptions.

Just as scholars and practitioners concerned with sustainable development have focused mainly on environmental management, those concerned with corporate social responsibility have focused on social and ethical issues such as human rights, working conditions, and so forth. The social principles of justice and inclusiveness, embedded in sustainable development, have entered the corporate agenda, even among firms making promising environmental efforts at a global scale. Corporate social responsibility research has focused on three main areas with respect to environmental management: (a) developing descriptions of the evolution of corporate environmental practices; (b) explaining external and interval drivers of why organizations adopt environmental practices; and (c) examining the link between proactive or beyond compliance environmental practices and profitability. This integration of corporate social performance with environmental performance presents a challenge to identify meaningful sustainability metrics instead of focusing on pollution or environmental data. In either case, the integration on traditionally nonbusiness issues like environmental protection, social justice, and sustainability is a challenging proposition for organizations in terms of structure, communication, leadership, and so forth.

A Model For Environmental Change: Overcoming The Green Wall

Ultimately, at the heart overcoming the Green Wall in organizations is an understanding of how individual change agents lead efforts for voluntary environmental leadership. The rigid history of business environmentalism and respective influence on business environmental behavior makes this type of organizational change a difficult task. A full understanding of organizational change is needed, as is an understanding of the role of the environmental champion in that process.

Environmental initiatives, on the smallest scale, and organizationwide environmental culture building, on the broadest scale of change, are hindered by the unique nature of environmental performance expectations and content. Simply put, any environmental intentions eventually need to be operationalized before they can have any effect. Here lies a big challenge, as the mix of technical, ethical, social, and competitive aspects of environmental issues is complex and hard to manage. Integration and changing environmental actions present challenges not only between

departments, but also among layers of larger firms. For instance, surveys of people at various organizational levels within major multinational firms have shown that pivotal jobholders further down the management hierarchy, such as plant managers, were much less confident about the ease of meeting environmental targets than were top managers.

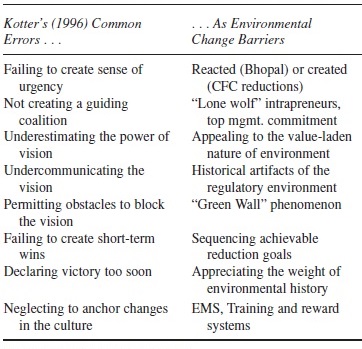

While many firms state environmental performance goals, what is needed is a better way to understand the resultant change necessary for achieving those goals. Applying John Kotter’s framework for change management to understand the barriers and steps for changing corporate culture is useful here. The framework for affecting organizational change has much to offer the field of environmental management and large and small firms alike. Ultimately, there must be environmental change agents at the highest levels of the firm (i.e., upper management commitment) and throughout (i.e., building an organizational environmental culture). There are eight common errors and resultant solutions to effectively implementing organizational change (see Table 2).

As Kotter (1996) states, “The biggest mistake people make when trying to change organizations is to plunge ahead without establishing a high enough sense of urgency in fellow managers and employees” (p. 4). In order to initiate change on any scale, the change agent must avoid complacency by establishing a sense of urgency or crisis. Unless the status quo of an organization is fundamentally questioned and corresponding, compelling reasons for change are effectively communicated, individuals and groups within organizations will not shift in policy or practice.

Table 2 Barriers for Firms’ Environmental Change

Corporate environmental change is intimately linked to this concept of the need for crisis and urgency in change initiatives. On a companywide and ultimately industry-wide basis, an event like Union Carbide’s Bhopal disaster, resulting in the creation of the Chemical Manufacturers Association Responsible Care initiative, for instance, serves as an example of reactive crisis driving change within an organization—and an entire industry (e.g., chemical industry). As stated previously, heightened regulations, demonstrations, consumer boycotts, and negative media attention all serve as external triggers for change, which firms must react to in order to compete. Yet, companies have also managed to avoid real crisis through the created sense of urgency on environmental issues. S. C. Johnson’s elimination of CFC use in products well ahead of the mandated ban on CFC use serves as an example. The weight of public pressure on environmental performance, whether real or not, also serves as the crisis and impetus for firm change and leadership.

Kotter’s (1996) second error gets to the core of failed environmental management initiatives in firms—failing to create a powerful guiding coalition:

Because major change is so difficult to accomplish, a powerful force is required to sustain the process. No one individual, even a monarch-like CEO, is ever able to develop the right vision, communicate it to large numbers of people, eliminate all the key obstacles, generate short-term wins, lead and manage dozens of change projects, and anchor new approaches deep in the organization’s culture. (p. 5)

Rosabeth Moss Kanter (1983) also reflects on the power to innovate and the need for empowerment. She describes the process effective change-makers use in building an empowered coalition—buy in, preselling, sanity check, tin cupping for organizational resources, and bargaining. Kanter states that managers use a process of bargaining and negotiation to accumulate enough information, support, and resources to proceed with an innovation.

Much of the literature in environmental management alludes to this need for coalition building, often deemed simply as gaining top management commitment to environmental initiatives or change within the organization. There is a need for having organizational power and resources to develop momentum for change. Yet, coalition building is part of the process for change, rather than simply an outcome. Unfreezing the organization from its current state does not happen simultaneously throughout the organization, but instead occurs within a limited number of members first. These are pockets in the organization where the new thinking exists. These members trigger change from within and when successful, infect change throughout the organization over time.

Like any corporate change initiative, developing a significant power base throughout the upper levels of the organization on an environmental initiative is necessary. If the intended change involves the total redirecting of environmental behavior by the firm, this coalition becomes crucial. This coalition determines the depth of influence a change initiative will have in the organization.

The historic bag-on-the-side view of environmental functions in business defines the problem that environmental managers in larger firms have had in building effective, organization wide coalitions in larger businesses. Only recently have environmental issues permeated to the upper layers of corporate decision making—the needed layer for creating coalitions that break organizational inertia and allow for change to occur. In all cases, the individual program champion must have sufficient power and authority (and autonomy perhaps) to lead change and overcome the greening barrier.

At both the organizational level and the individual level, environmental change in firms has suffered from an underestimation of the power of vision, Kotter’s third error. This common failure has its roots in the dominance of environmental legislation and regulation. Federal statutes protecting air, water, and land were mostly prescriptive in both technology (i.e., mandated control technology for water emissions under the Clean Water Act) and in the manner of handling environmental responsibilities (i.e., reporting, permitting, etc.). This mode of environmental control was, in time, internalized as a norm of behavior in the majority of firms, specifically in the United States.

As Kotter (1996) states, these two modes, authoritarian decree and micromanagement, “often work poorly . . . [and] leads to an increasingly unacceptable amount of time” (p. 68). for change. This manner in which firms’ environmental behavior was externally controlled led environmental professionals into rigidly defined boxes, where prescriptive micromanagement was the only answer—ineffective for guiding business decisions. Potential environmental change agents in organizations, and thus organizations themselves, have failed to use the power of vision to fuel environmental change.

Kotter (1996) continues:

Vision refers to a picture of the future with some implicit or explicit commentary on why people should strive to create that future. In a change process, a good vision serves three important purposes. First, by clarifying the general direction for change, by saying the corporate equivalent of “we need to be south of here in a few years instead where we are today,” it simplifies hundreds or thousands of more detailed decisions. Second, it motivates people to take action in the right direction, even if the initial steps are personally painful. Third, it helps coordinate the actions of different people, even thousands and thousands of individuals, in a remarkably fast and efficient way. (p. 68)

Leadership defines an organization’s vision and is related to the need for top management commitment and the coalition-building steps. Likewise, a stated vision responds to crisis—created or actual—that helps trigger change throughout an entire organization. It is the focused, total response to that urgent environmental responsibility and corresponding business goal. The formation of corporate vision and mission statements to address environmental concerns beyond mere regulatory requirements serves as an example in larger firms.

Along with a weak sense of vision, environmental change initiatives have often been stifled by a simple lack of commitment throughout the organization. With any type of organizational change, people often have difficulty because of the sheer magnitude of the task. Getting people to understand and accept a particular vision is usually an enormously challenging undertaking. This is especially true with environmental change initiatives in larger organizations. Historically, environmental issues have been perceived throughout business organizations as cost generating in nature and peripheral at best. Changing the actions of an entire population of an organization relies on communicating the intentions of that change effort—not often done on issues of environmental concern. This lack of communication among environmental staff and other members of the company is at the heart of the Green Wall phenomenon. Once again, the historic treatment of environmental management concerns by business has created divisions among environmental staff and the rest of the company.

The Environmental Change Agent

While Kotter’s first four elements for organizational change seem to address the need for unfreezing the organization, the next three errors in the change process—permitting obstacles to block the new vision, failing to create short-term wins, and declaring victory too soon—each relate to the act of moving the organization in a new direction. Even if environmental goals are effectively created and plans are made, action (or change) does not automatically take place. Change agents must address the wide gap between plan and action.

With any intended change of direction in an organization, a corresponding series of obstacles forms quickly to block the change process. As Kotter (1996) states,

New initiatives fail far too often when employees, even though they embrace a new vision, feel disempowered by huge obstacles in their paths. Occasionally, the roadblocks are only in people’s heads and the challenge is to convince them that no external barriers exist. But in many cases, the blockers are very real. (p. 10)

These blockers for change include structures (formal structures making it difficult to act), skills (a lack of needed skills undermines action), systems (personnel and information systems make it difficult to act), and superpowers (bosses discourage actions aimed at implementing the new vision).

An important task is to handle criticism or opposition that may jeopardize the project. As Rosabeth Moss Kanter (1983) states,

I could identify a number of tactics that innovators used to disarm opponents: waiting them out (when the entrepreneur had no tools with which to directly counter the opposition); wearing them down (continuing to repeat the same arguments and not giving ground); appealing to larger principles (tying the innovation to an unassailable value or person); inviting them in (finding a way that opponents could share the ‘spoils’ of the innovation); sending emissaries to smooth the way and plead the case (picking diplomats on the project team to periodically visit critics and present them with information); displaying support (asking sponsors for a visible demonstration of backing); reducing the stakes (de-escalating the number of losses or changes implied by the innovation); and warning the critics (letting them know they would be challenged at an important meeting—with top management, for example). (p. 231)

Environmental management differs from other corporate concerns due to, among other factors, its moral-ethical features that often deviate from typical strategic business concerns. This added characteristic of environmentally related organizational change, unlike the drive for a new accounting system or shepherding a new product through the organization, can create extraordinary resistance. This is specifically due to the strong feeling and emotion tied to the natural environment by people, and the antagonistic history the public (i.e., employees) have experienced and been exposed to by the media for the past 35 years. Along with an intentional blocking of environmental initiatives, there are also instances of unintentional disconnects between corporate leadership and environmental departments.

Change also has a component of time that can snuff out any new environmental strategy or course of action. According to Kotter, major change takes time, sometimes lots of time. Allies will often stay loyal to the change process no matter what happens. Most other people expect to see convincing evidence that all the effort is paying off. Finally, nonbelievers have even higher standards of proof. They want to see clear data indicating that the changes are working, that there is or will be a benefit to the organization, and that the change process is not absorbing so many resources in the short term as to endanger the organization.

As such, it is important to generate short-term wins along the way. Because of its often divisive and litigious history and its value-laden nature, environmentalism has the potential to stir emotions of those critics in the organization intending on dividing environmental responsibilities from economic goals.

Effective environmental change agents find the urgent reason to take that first step, use the vision of the distant mountains as their guide, select the right organizational members to walk with them, and draw more followers throughout the organization by sequencing the journey one step at a time. In order for an environmentally benign culture change to proceed, it is essential that the organization gains positive experience from the environmentally improved actions during the period when old and new ways of doing things compete. Reinforcement of the success of the new practices speed the cultural shift and may be necessary for the change to proceed.

There have been instances of successful organizational environmental change which point to the importance of generating these short-term wins. Integrating environmental concerns into the new product development process, building internal cross-function advisory boards for guiding environmental decisions, or sequencing change allows for staff acceptance and organizational retention. Likewise, internal praise (i.e., awards, ceremonies, and reward structures), and external praise (i.e., positive media coverage or environmental NGO endorsement) for such actions serves to accelerate the change. All of this has implications for those organizations developing and managing voluntary environmental initiatives.

Finally, to allow for organizational movement after unfreezing, Kotter seeks to avoid the seventh common error for change—declaring victory too soon—by nurturing the successes along the way and leveraging those successes for more change—a continuous improvement model for change. The organizational field shaping business environmentalism is constantly changing. In the recent decade, regulations and policy triggers have evolved, giving way to management systems-based appeals on an international level. Tools like Environmental Management Systems are becoming more commonplace, building from the total quality movement of the past, with firms looking to integrate their environmental management practices within a plan-do-check-act framework. Likewise, the competitive environment is always changing, and stakeholder expectations are equally dynamic. As such, even when the Green Wall is negotiated and scaled, there is a need to ensure the change is dynamic and perpetual by assuming new barriers, driven internally and externally, may enter the firm structure at any time. For instance, the loss of a key ally at the upper management level may necessitate a revisiting of the steps outlined above—building a new coalition with new employees and leaders in the firm.

Institutionalizing Business Environmentalism: Anchoring The Change

The final element in the change process involves refreezing, anchoring the change in the culture. An organization’s culture is that mix of structure, systems, and staff that give it a deeply rooted sense of self. In the simplest terms, the culture of an organization is the way we do things around here. Edgar Schein (1992) has written extensively on organizational culture and offers the image of an iceberg to further define it. What we see—consumers, employees, investors, and stakeholders alike—is the above water manifestation of the organization. Below the surface, however, are the elements and attitudes that truly give the organization its meaning. It is the collective consciousness of attitude and behavior that defines a group or organizational culture. As such, culture change is long and difficult. Changing an individual’s attitude and behavior is one thing; changing the collective attitudes and behaviors of a diverse group of individuals is something completely different.

As such, many change efforts fail due to an inability to sustain that change against the status quo. This is true for environmental change efforts as well. Leaders create and change cultures, while managers and administrators live within them. The goal of environmental leadership, and sustainability for that matter, culminates with the question of profound change in organizational culture. This cultural component of an organization stands as a relatively new area for researchers and practitioners alike.

Affecting individual behavior, values, and basic assumptions, requires an enormous amount of time, resources, and effort. Yet, given the value-laden nature of environmentalism, focusing on firm culture for anchoring change allows for a more effective implementation of firm-level environmental behavior. The differences between symbolic change and real change are exposed when studying an organization’s culture. The gap between ideas, plans, and actions are more readily seen. Even if the company mission statement is phrased in terms of stewardship for future generations, a defensive climate may lead to providing information on specific issues that challenge commercial interests or organizational dynamics. As a result, environmental issues become ignored.

There is a difficulty and importance in changing the deeper culture of the organization to ensure actions and behaviors are sustained beyond the life of the leader shaping the change process. Kotter (1992) defined additional factors of anchoring change—including the need for results previous to the cultural shift, lots of time communicating intentions, possible staff changes, and changes in promotion and reward processes. Individual reward and organizational performance is once again a crucial lever for change. So too is consistent and constant positive feedback, both from within the organization and from outside actors (i.e., investment community, consumers). As the business of business is profit generation, at least in some measure, if the market does not react positively to change resulting from breaking down the Green Wall in organizations, then those changes risk a short life as well.

Looking at an organization’s culture is essential for the identification of underlying factors that give rise to unsustainable practices. This is an important component of any change process. Addressing a firm’s culture is, then, necessary in the development of positive environmental behavior on an organizationwide basis. Anchoring change, it seems, is the most difficult, yet most essential aspect for sustained change efforts.

Summary: Moving Beyond The Green Wall

Research in organizational change management—for quality, customer service, or heightened competitive awareness —offers a wealth of information to the study of corporate environmental behavior. Environmental change agents, or champions, like their traditional counterparts, require power, tools, resources, peer and upper management commitment, systems for change, and persuasion tactics for effecting change. Unlike their counterparts, however, environmental champions within the firm face the historically driven weight of environmentalism which creates barriers against change. The cognitive myth that environmental responsibilities and business goals are mutually exclusive is being dispelled as leading firms redefine environmentally driven competitive advantage, but these myths are powerful barriers for sweeping change.

This Green Wall for environmental change, while increasingly scaleable, continues to be a barrier for organization-, industry-, and society-wide change. As the environmental movement in business slowly gives way to the more complex and comprehensive sustainability movement, a new set of obstacles for change are likely to become pervasive. Issues of social justice, fair wages, and quality of life are being wrapped together with environmental concerns for business leaders. This complicates the perspective even more. Yet, as the model explored in this research-paper shows, any change process must include an awareness of how the content of change interacts with the process of change, in particular the initial starting point.

Bibliography:

- Ascolese, M. (2003, June). European and U.S. multinationals place different emphases on corporate sustainability, PricewaterhouseCoopers finds: Environmental and social performance a priority for Europeans; an opportunity for Americans. Management Barometer, 21. Retrieved from https://www.sustainability-reports.com/titel-482/

- Berry, M. A., & Rondinelli, D. A. (1998). Proactive corporate environmental management: A new industrial revolution. Academy of Management Executive, 12(2), 38-50.

- Brundtland, G. (1987). Our common future: The world commission on environment and development. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/publications/publications.htm

- Cairncross, F. (1991). Costing the earth: The challenge for governments, the opportunities for business. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Darnall, N., Carmin, J., Kreiser, N., & Mil-Homens, J. (2003, December). The design & rigor of U.S. voluntary environmental programs: Results from the VEP survey. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228262765_The_Design_Rigor_of_US_Voluntary_Environmental_Programs_Results_from_the_VEP_Survey

- de Steiger, J. E. (1997). Age of environmentalism. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Dickinson, E. (2000). Editorial column. BOAT/US Magazine, 11, 28-29.

- Easterbrook, G. A. (1995). Moment on the earth: The coming age of environmental optimism. New York: Pengiun Books.

- Elkington, J. (1998). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada: New Society Publishers. Fischer, K., & Schot, J. (Eds.). (1993). Environmental strategies for industry: International perspectives on research needs and policy implications. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Frankel, C. (1998). In earth’s company: Business, environment, and the challenge of sustainability. Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada: New Society Publishers.

- Hoffman, A. (1998). From heresy to dogma: An institutional history of corporate environmentalism. San Francisco: New Lexington Press.

- Hoffman, A. (2000). Corporate environmental strategy: A guide to the changing landscape. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Kanter, R. M. (1983). The change masters: Innovation and entrepreneurship in the American corporation. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Kotter, J. (1996). Leading change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Kotter, J., & Heskett, J. L. (1992). Corporate culture and performance. New York: Free Press.

- Petulla, J. M. (1988). American environmental history. Columbus, OH: Merrill Publishing Company.

- Piasecki, B. (1995). Corporate environmental strategy: The avalanche of change since Bhopal. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Piasecki, B., Fletcher, K., & Mendelson, F. (1999). Environmental management & business strategy: Leadership skills for the 21st century. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Reinhardt, F. L., (2000). Down to earth: Applying business principles to environmental management. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Rondinelli, D., & Berry, M. (2000). Corporate environmental management and public policy: Bridging the gap. The American Behavioral Scientist, 44(2), 168-187.

- Roper Starch/S. C. Johnson & Son, Inc. (1993). The environment: Public attitudes and individual behavior, North America: Canada, Mexico, United States. Racine, WI: Roper Starch.

- Schein, E. H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Schmidheiny, S. (1993). Changing course: A global business perspective on development and the environment. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Shelton, R. (1995). Hitting the green wall: Why corporate programs get stalled. Corporate Environmental Strategy: The Journal of Environmental Leadership, 4(3), 34-46.

- U.S. Bureau of Census. (2000). Statistics of U.S. businesses. Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/55000.html

- U.S. Small Business Administration. (2003). Office of advocacy— Research and statistics. Retrieved from https://advocacy.sba.gov/

- Winsemius, P., & Guntram, U. (1995). Towards a top management agenda for environmental change. Amsterdam: McKinsey & Associates.