Sample Corporate Culture Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

1. How To Think About And Define ‘Culture’

To understand corporate culture one must first under-stand the concept of culture. A chronic issue in conceptualizing culture is whether to think of culture as a static property of a given organization—its shared customs, beliefs, norms, values, and tacit assumptions, or whether to think of culture as a dynamic human process of constructing shared meaning (Frost et al. 1985). Culture creation is one of the unique characteristics of humans, being based on our capacity to be self-conscious and able to see ourselves and others from each others’ points of view. It is this reflexive capacity of humans that makes culture possible. At the same time, it is the human need for finding meaning that creates the motivation for culture stabilization. Without some predictability, social intercourse be-comes too anxiety provoking. Developing shared meanings of how to perceive, categorize, and think about what goes on around us is necessary to avoid the catastrophic anxiety that would result from reacting to everything as if it were a new phenomenon (Weick 1995).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Given these human characteristics, it then becomes clear that culture is both a process and a state. In new situations, shared meanings must be constructed through a social learning process. As these meanings help the participants to make sense of their world they become stabilized and can be viewed as ‘states.’ At the same time, as the members of a group interact, they not only recreate and ratify prior meanings but also construct new meanings as new situations arise.

A useful way to think about this issue is to take a cue from the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins (1985), who argues that one cannot really understand certain social phenomena without understanding both the historical events and the cultural meanings attributed by the actors to those events. While it is undeniably true that we produce and reinforce culture through perpetual enactment and sense making, it is equally true that the actors in those same social events bring to them some prior meanings, stereotypes, and expectations that can only be understood in a historical context. Culture production in the enactment sense, then, is either the perpetuation of or a change of some prior state, but that prior state can be thought of as ‘the culture’ up to that point. And one can describe that culture as if it were a ‘state’ of the existing system, even though one knows that the system is dynamic and perpetually evolving. The direction of that evolution will be a product of several forces: (i) technological and physical changes in the external environment; (ii) changes in the internal dynamics of the social system; and (iii) historical circumstances that are fortuitous or serendipitous.

For example, let me offer my oversimplified summary of Sahlins’s very sophisticated analysis of the death of Captain Cook at the hand of the Hawaiians. Because Captain Cook was viewed as a God (as predicted in the Hawaiian mythology), the sexual favors offered to his sailors by the Hawaiian women were viewed as gifts and as opportunities to relate to the divine. The sailors’ cultural background defined this as a version of prostitution, however, for which they felt they should pay. When they offered the women something in exchange for the sex, the women asked for something that was scarce in the society, namely metal. Once the loose metal on board the ships had been used up, the sailors began to pull nails from the ship itself, weakening it structurally. Hence, when Captain Cook set sail he discovered that the ships needed repair and/ordered a return to harbor. In Hawaiian mythology a God returning under these circumstances had to be ritually killed. At the same time, Hawaiian social structure was undergoing change and became permanently altered because the subordinate role of women in the society was altered by their ability to acquire metal, a scarce resource that gave them social power.

When one contemplates this wonderful analysis it appear pointless to argue whether culture should be viewed as a state of the system or as a process of enactment. Clearly there was a culture in Hawaii and a different culture on board the British ship, and clearly the interaction of these two cultures produced events that had a profound impact on both of these cultures.

2. Implications For ‘Organizational’ Culture Analysis

The major lesson of Sahlins’s analysis is that when we ha e access to historical data we should use it. Organizations have defined histories. Therefore, when we analyze organizational cultures we should reconstruct their histories, find out about their founders and early leaders, look for the critical defining events in their evolution as organizations, and be confident that when we have done this we can indeed describe sets of shared assumptions that derive from common experiences of success and/or shared traumas. And we can legitimately think of these sets of assumptions as ‘the culture’ at a given time. That description will include subcultures that may be in conflict with each other, and there may be subunits that have not yet had enough shared experience to have formed shared common assumptions. In other words, culture as a state does not have to imply unanimity or absence of conflict. There can be some very strongly shared assumptions, and large areas of conflict and/or ambiguity (Martin 1992) within a given cultural ‘state.’

At the same time, we can study the day-to-day interactions of the members of an organization with each other and with members of other organizations to determine how given cultural assumptions are reinforced and confirmed, or challenged and dis-confirmed. We can analyze the impact of these perceptual interactive events in order to understand how cultures evolve and change. This process could be especially productive in mergers, acquisitions, and joint ventures of various sorts. Whether one chooses to focus one’s cultural research on building typologies of cultural ‘states,’ categories that freeze a given organization at a given point in time, or on analyzing the moment to moment interactions in which members of a given social system attempt to make sense of their experience and, in that process, reinforce and evolve cultural elements, becomes a matter of choice. Both are valid methodologies and in practice they should probably be combined.

3. A Formal Definition Of Culture

Culture as a property or process of any group can now be defined as: a pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group has learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems (Schein 1992).

Once these patterns have been learned they function to reduce anxiety and provide moment-to-moment meaning and predictability to daily events. Or, as Trice and Beyer (1993) put it: ‘Human cultures emerge from people’s struggles to manage uncertainties and create some degree of order in social life’ ( p. 1). Note that patterns of overt behavior are not part of the formal definition because such patterns can arise through other causes such as common instinctive patterns (e.g., ducking when we hear a loud noise) or by common reactions to a common stimulus (e.g., everyone running in the same direction to avoid some threat). If one understands the shared basic assumptions, one can determine which regularities of behavior are ‘cultural’ and which ones are not. One cannot, however, infer the assumptions just by observing behavior.

4. A Conceptual Model For Analyzing Culture

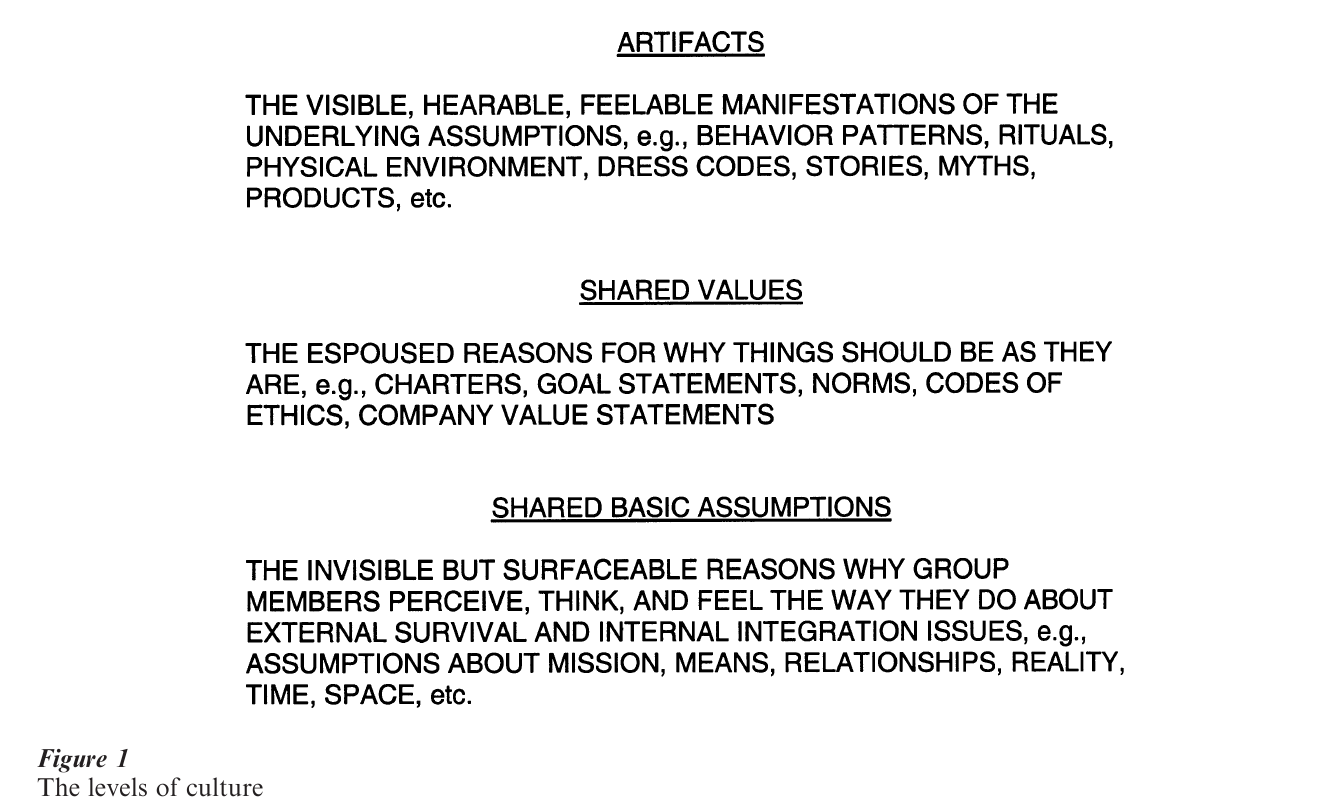

Whether one chooses to analyze culture as a state or as a process, it is helpful to differentiate the levels at which culture as a shared phenomenon manifests itself. Any group, organization, or larger social system can be analyzed in terms of (i) its visible and feel able ‘artifacts,’ (ii) its espoused beliefs and values; and/or (iii) its less visible, taken for granted shared basic assumptions (see Fig. 1).

This model is useful in two ways: (i) it helps a novice observer of organizational culture to differentiate the superficial manifestations and espoused values that most organizations display from the cultural substrate or essence, the tacit, shared assumptions that drive the day-to-day behavior that one observes; and (ii) the differentiation of levels is a necessary conceptual tool in helping an organization to decipher its own culture.

To further understand these distinctions, especially the distinction between espoused values and shared tacit assumptions, it is necessary to take a historical evolutionary point of view toward culture formation. If we take a typical business organization, the process starts with one or more entrepreneurs who found a company based on some personal beliefs and values. As they hire others to work with them they will either choose those others on the basis of their compatibility or will socialize newcomers to the beliefs and values that they regard as core to running the new business. The founders’ beliefs and values will cause the organization to make decisions in its environment, and if those decisions are successful, the newcomers will begin to entertain collectively the idea that the founder’s beliefs and values must be ‘correct.’ As the environment continues to reinforce the behavior of the organization, what was originally the founder’s personal beliefs and values gradually come to be shared and imposed on new members as the organization grows. If this success cycle continues, these shared beliefs and values gradually come to be taken for granted, drop out of awareness, and can therefore be thought of as ‘taken for granted assumptions’ that become increasingly non-negotiable.

This process of culture formation will occur not only in reference to the organization’s primary task in its various external environments but also with respect to its internal organization as well. Those founder beliefs and values, which make life livable and reduce interpersonal anxiety, will gradually come to be taken for granted and come to be tacit assumptions about the ‘correct’ way to organize. But in both domains the driving force is what works. Culture is the result of successful action. If things do not work out the group will disappear.

A basic need in human groups is to justify what they do. And, paradoxically, the justifications often are not the same as the tacit assumptions that actually determine the behavioral regularities. Thus groups create ideologies, aspirations, visions, and various other kinds of ‘espoused values’ which may or may not correspond isomorphic ally with the tacit assumptions. The most difficult aspect of deciphering organizational cultures, then, is to determine to what extent the claimed espoused values actually correspond to the behavioral regularities observed and, if not, to deter-mine what the shared tacit assumptions are.

5. How To Describe Cultures

There are three approaches to describing cultures: (i) profiling them on various preselected dimensions; (ii) creating conceptual typologies into which to fit given cultures; and/or (iii) clinical or ethnographic descriptions that highlight unique aspects of a given culture.

Among the profiling approaches, one of the most widely used is Hofstede’s four dimensions based on factor analyzing questionnaire responses—Individualism (vs. Groupism), Masculinity (the perceived gap between male and female roles), Tolerance for Ambiguity, and Power Distance (the perceived distance between the most and least powerful in the society). These dimensions used originally to describe national cultures but have also been extended to descriptions of organizational cultures (Hofstede 1980, 1991).

A different approach has been to use sociological dimensions developed by Parsons (1951) and elaborated by Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck (1961) as a way of creating profiles of a given organization and identifying critical value issues—universalism vs. particularism, individualism vs. collectivism, affectively charged vs. neutral, specific vs. diffuse, time orientation, and degree of control over nature (Hampden-Turner and Trompenars 1993, Trompenars 1993). A third version of this approach is to take one or two dimensions, consider them to be conceptually central, and create a typology based on a two-by-two table with those dimensions. Cameron and Quinn (1999) use (a) Flexibility vs. Stability and Control and (b) Internal Integration vs. External Differentiation to create four types of cultures—Clan, Adhocracy, Hierarchy, and Market. Goffee and Jones (1998) use the dimensions of Degree of Solidarity and Degree of Sociability to create four types—Networked, Communal, Fragmented, and Mercenary. Among the typologies we have Likert’s Systems 1 to 4, Harrison and later Handy’s ‘Gods of Management,’ Mc-Gregor’s Theory X and Theory Y, Ouchi’s Theory Z, and the more popular distinctions between ‘command and control’ vs. ‘committed and empowered’ (Likert 1967, Handy 1978, McGregor 1960, Ouchi 1981).

The clinical or ethnographic approach attempts to deal with any given culture as a unique pattern of shared assumptions around issues that are not known before the clinician researcher is on the scene as an observer and active inquirer (Schein 1987, 1992, 1999). The prime objection to questionnaires as research tools for the study of culture is that they force us to cast the theoretical net too narrowly. The advantage of the ethnographic or clinical research method is that we can train ourselves consciously to minimize the impact of our own models and to maximize staying open to new experiences and concepts we may encounter. In the end we may well sort those experiences into the existing categories we already hold. But at least we will have given ourselves the opportunity to discover new dimensions and, more importantly, will have a better sense of the relative salience and importance of certain dimensions within the culture we are studying. The issue of salience is very important because not all the elements of a culture are equally potent in the degree to which they determine behavior. The more open group oriented inquiry not only reveals how the group views the elements of the culture, but, more importantly, tells us immediately which things are more salient and, therefore, more important as determinants.

As to the categories themselves I have found it empirically useful to start with a broad list of ‘survival functions’—what any group must do to survive in its various environments and fulfill its primary task, and ‘internal integration functions’—what any group must do to maintain itself as a functioning system. This distinction is entirely consistent with a long tradition of empirical research in group dynamics that always turns up two critical factors in what groups do—(i) task functions; and (ii) group building and maintenance functions. Ancona and others have pointed out that we must add a third set to these two— boundary maintenance functions (Ancona 1988). Task and boundary maintenance functions are external survival issues, and group building and maintenance functions are internal integration issues. We may then construct different lists of what specific dimensions of behavior, attitude, and belief we will look for in each domain, but at least we have a model that forces us to cast the net widely, and a reminder that culture is, for the group, the learned solution to all of its external and internal problems.

If we then look a little deeper, drawing again on anthropology and sociology, we find broad cultural variations around deeper, more abstract issues such as those developed by Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck. Also useful is the work of England (1975) on managerial values which deals specifically with how in a given culture one arrives at ‘truth.’ If one combines these dimensions with some of the dimensions identified by Edward Hall (1966, 1976, 1983) on concepts of space and spatial relationships, and with more recent concepts about the nature of the ‘self’ in different cultures, one has a pretty good template of what culture covers at this deeper level.

6. Does Corporate Culture Matter?

Several claims based on various different kinds of research have tried to show a connection between the strength and/or type of culture and economic performance (Deal and Kennedy, 1982, Denison 1990, Kotter and Heskett 1992, Collins and Porras, 1994). The problem is that different kinds of cultural dimensions relate to different kinds of environments in ways that are not entirely predictable. The best way to summarize, then, is to say that culture certainly influences economic performance, but the manner in which this occurs remains highly variable. A culture that can be very functional in one environment or at one stage in a company’s evolution can become dysfunctional and cause that same company to fail. Culture needs to be analyzed and understood, but until much more research has been done, one cannot make generalizations about its impact.

Bibliography:

- Ancona D G 1988 Groups in organizations: Extending laboratory models. In: Hendrick C (ed.) Annual Review of Personality and Social Psychology: Group and Intergroup Processes. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA

- Cameron K S, Quinn R E 1999 Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA

- Dennison D R 1990 Corporate Culture and/organizational Eff Wiley, New York

- England G 1975 The Manager and His Values. Ballinger, New York

- Frost P J, Moore L F, Louis M R, Lundberg C C, Martin J (eds.) 1985 Organizational Culture. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

- Goffee R, Jones G 1998 The Character of a Corporation. Harper, New York

- Hall E T 1966 The Hidden Dimension. Doubleday, New York

- Hall E T 1976 Beyond Culture. Doubleday, New York Hall E T 1983 The Dance of Life. Doubleday, New York

- Hampden-Turner C, Trompenars A 1993 The Se en Cultures of Capitalism. Doubleday-Currency, New York

- Handy C 1978 Gods of Management. Pan Books, London

- Hofstede G 1980 Culture’s Consequences. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA

- Hofstede G 1991 Cultures and/organizations. McGraw-Hill, London

- Kluckhohn F R, Strodtbeck F L 1961 Variations in Value Orientations. Harper, New York

- Kotter J P, Heskett J L 1992 Corporate Culture and Performance. Free Press, New York

- Likert R 1967 The Human Organization. McGraw-Hill, New York

- Martin J 1992 Cultures in Organizations. Oxford University Press, New York

- McGregor D 1960 The Human Side of Enterprise. McGraw-Hill, New York

- Ouchi W G 1981 Theory Z. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA

- Parson T 1951 The Social System. Free Press, Glencoe, IL

- Sahlins M 1985 Islands of History. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

- Schein E H 1987 The Clinical Perspective in Fieldwork. Sage, Newbury Park, CA

- Schein E H 1992 Organizational Culture and Leadership (2nd). Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA

- Schein E H 1999 The Corporate Culture Survival Guide. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA

- Trice H M, Beyer J M 1993 The Cultures of Work Organizations. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

- Trompenars A 1993 Riding the Waves of Change. Economist Books, London

- Weick K E 1995 Sensemaking in Organizations. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA