View sample The Competitive Advantage Of Interconnected Firms Research Paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a management research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

In recent years, the formation of interfirm alliances has become a popular practice, leading to the evolution of interconnected firms, which are embedded in alliance networks. This entry seeks to account for the factors driving the competitive advantage of such firms by highlighting the role of network resources. It distinguishes shared resources from nonshared resources in alliances, identifies various types of rent,1 and illustrates how firm-specific, relation-specific, and partner-specific factors determine the contribution of network resources to the rents that interconnected firms extract from their alliance networks. This entry revisits the assumptions of the resource-based view and suggests that the nature of relationships may matter more than the nature of resources for the competitive advantage of interconnected firms. By integrating competition and collaboration as vehicles of value creation and appropriation, this entry seeks to advance our understanding of the challenges and prospects of managing dynamic organizations in the 21st century. In a world of interconnected firms and interdependent corporate strategies, traditional perspectives on how firms gain competitive advantage must be revisited and more attention must be paid to emerging theories of the firm.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Introduction

At the turn of the 21st century, the competitive environment has changed dramatically. As the reliance on interfirm alliances (henceforth termed alliances) has gained popularity, firms can no longer be considered simply as independent entities competing for favorable market positions and protecting their core assets from imitation and appropriation. Instead, firms have become interconnected in the sense that they engage in multiple simultaneous alliances. Alliances can be defined as collaborative arrangements among independent firms, involving exchange, sharing, and co-development activities designed to achieve the strategic goals of these firms. Alliances take different forms, including joint ventures, joint marketing initiatives, and affiliation in research consortia.

Although alliances have been extensively studied in the fields of economics, sociology, organization theory, international business, and strategic management, traditional theories of the firm offer limited explanations of the interconnected firm phenomenon because of their emphasis of competitive dynamics. On the one hand, such traditional theories undervalue the important contribution of alliances to firm behavior and performance. On the other hand, the proliferating alliance literature offers mainly analysis of dyadic relationships or network structures rather than a firm-centric perspective. Hence, a need arises for a theory that explains how interconnected firms evolve and how their alliance networks affect their performance.

Theories of the firm address three questions concerning the nature of the firm: (a) Why do firms emerge; (b) why do firms differ in their scale, scope, and organization of activities; and (c) what accounts for heterogeneity in their performance? While the strategic management literature is mostly concerned with the latter question, understanding of firm nature is necessary for the development of a theory of the firm. The validity of different theories of the firm has been a subject for a fertile debate in the strategic management literature. Although some of these theories can be broadly used, their assumptions require scrutiny when applied to the study of the interconnected firm. For example, with his microanalytic approach, Williamson (1975) adopted the transaction as the unit of analysis, arguing that the firm emerges in order to economize on transaction costs accrued due to bounded rationality and opportunistic behavior. Transaction-cost economics offers an explanation of firm existence but falls short of providing a comprehensive theory of the interconnected firm because it tends to consider markets and hierarchies as two discrete governance modes and its atomistic unit of analysis cannot capture the idiosyncrasies of interconnected firms that typically integrate internalized and market transactions. In addition, it disregards interdependence in partners’ exchange decisions and, as Zajac and Olsen (1993) noted, overemphasizes contractual aspects of transactions at the expense of process issues.

Similarly, the resource-based view has emerged as a theory of the firm that addresses the three fundamental questions of existence, interfirm differences, and performance heterogeneity. It conceptualizes firms as heterogeneous entities consisting of bundles of idiosyncratic resources and suggests that the firm exists where it has advantage over the market in deploying productive resources. It goes one step further to explain the superiority of a particular firm relative to other firms and emphasizes performance differences across firms. However, the resource-based view maintains that resources that confer competitive advantage must be confined by firm boundaries. This proprietary assumption limits accurate evaluation of interconnected firms, whose performance depends not only on the contribution of internal resources but also on network resources. Network resources reside in alliances in which the interconnected firm is involved rather than within the scope of the firm’s organizational boundaries. Nevertheless, Gulati (1999) suggested that they provide strategic opportunities and affect firm behavior and value. Hence, the fundamental assumptions of traditional theories of the firm, which de-emphasize the role of network resources, limit their applicability in the case of interconnected firms.

The relational view, which has been advanced by Dyer and Singh (1998) overcomes some of these limitations by acknowledging that critical resources may span firm boundaries. The relational view advances a theory of value creation in alliances and points to the fact that interconnected firms can accrue some rents from alliances. Such relational rents accrue to alliance partners through combination, exchange, and codevelopment of idiosyncratic resources. The relational view articulates the logic of value creation in alliance networks but leaves open the question of what drives appropriation of relational rent by interconnected firms.

After discussing the emergence of the interconnected firm and illustrating some of the limitations of traditional theories of the firm, this entry incorporates the notion of network resources in order to evaluate the competitive advantage of interconnected firms. Instead of applying the traditional resource-based view for explaining the phenomenon of interconnected firms, it revisits the theoretical underpinning of the resource-based view by considering the implications of alliance networks. It reveals how an inter-connected firm can extract value from resources that it does not fully own or control, thus allowing for the estimation of various types of rent that the firm generates through its usage of network resources. The proposed model distinguishes shared resources from nonshared resources and illustrates how firm-specific, relation-specific, and partner-specific factors determine the contribution of network resources to the rents that firms extract from their alliance networks. For example, it suggests that interconnected firms can benefit not only from jointly created relational rents but also from spillover rents, which are extracted in an involuntary way for unintended purposes. It highlights some unique aspects of interconnected firms, explaining why the nature of relationships may matter more than the nature of resources in creating and sustaining competitive advantage in networked environments.

The Emergence Of The Interconnected Firm

Since the early 1980s, scholars have observed the proliferation and increased popularity of alliances (Gulati, 1998; Hagedoorn, 1993). The recent growth in alliance formation can be ascribed to exogenous changes in the competitive environment. For example, in some industries, Schumpeterian competition has evolved, which is characterized by rapid technological innovation and turbulent market conditions. In such an environment, alliances emerge to allow flexible and more rapid adjustment to changing market conditions and to reduce time to market in response to shortened product life cycles. In the face of increased pressures for globalization, alliances also assist in bridging national boundaries, providing market access, and extending competitive advantage to emerging markets. More generally, alliances reduce market uncertainty and stabilize the firm’s competitive environment by forming norms of reciprocity that establish commitment and regulate exchange transactions. Prior research confirms that firms establish alliances to enhance predictability and share costs and risks (Eisenhardt & Schoonhoven, 1996; Powell, Koput, & Smith-Doerr, 1996) but also recognizes path dependence in alliance formation wherein the firm’s prior alliances guide its choice of new alliance partners (Ahuja, 2000; Gulati, 1995). Together, these forces have led to tremendous growth in the number of alliances and, consequently, to the proliferation of interconnected firms.

The emergence of interconnected firms is a contemporary phenomenon. Although alliances had been formed in earlier decades, they were conceived of as ad hoc arrangements serving specific needs. Nowadays, more firms engage in alliance formation and participate in multiple simultaneous alliances. For example, based on a sample of publicly traded firms in the software industry, the percentage of interconnected firms has increased from 32% to 95%, and the size of a typical alliance network rose from 4 alliances per firm to over 30 alliances per firm during the 1990s, demonstrating the rapid evolution of interconnected firms in this industry (Lavie, 2004). Not only has the number of alliances increased, but the scope of alliances has also been extended. Whereas firms have previously engaged in alliances for performing relatively simple peripheral activities, in recent years, alliances have been used at various stages of research and development (R&D), production, and marketing in almost any industry. Corroborating this claim, a Booz-Allen & Hamilton survey indicated that the portion of revenues that interconnected firms extract from their alliances increased from 2% in 1980 to 19% in 1996. Another survey, conducted by Accenture, attributed 16% to 25% of median firm value to alliances. In sum, interconnected firms have been forming alliances in increasing numbers and have assigned to their alliance networks a central role in the development and operation of their businesses.

The emergence of the interconnected firm underscores the role of alliance partners as dominant stakeholders that form an evolving interface between the firm and its environment. In rapidly changing environments, alliance partners provide the interconnected firm with an efficient mechanism for obtaining nontradeable resources, timely information, market access, and referrals. A firm becomes interconnected when it forms its first alliance and ceases to be interconnected when it dissolves its last alliance. Firms experience different degrees of interconnectedness over time. In the embryonic stage of evolution, interconnected firms operate a limited number of alliances, but these alliances are critical for their survival and performance. The more affluent the firm with internal resources, the more attractive it becomes to potential partners, but at the same time, it is less dependent on network resources and, thus, less motivated to form additional alliances. Therefore, the firm’s motivation for forming alliances will be greatest at the embryonic stage of evolution when it faces a saturated market or economic slowdown or when it undergoes a strategic change or restructuring. Ironically, these are likely to be the occasions when the interconnected firm is less attractive to partners. Stated differently, the interconnected firm experiences excessive demand for alliance partners early and late in its life cycle or at the verge of a disruptive change, whereas oversupply of prospective partners exists for established firms that operate in stable competitive environments.

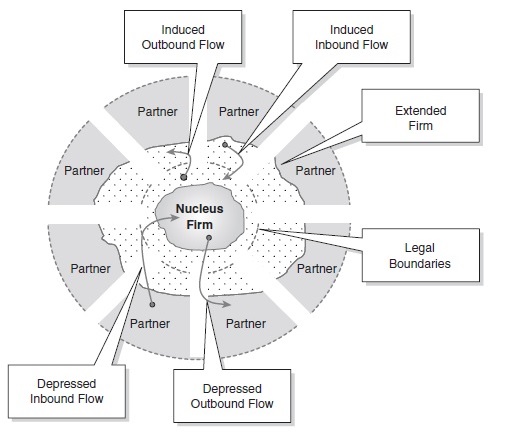

Figure 1 The Competitive Advantage of Interconnected Firms

The evolution of the interconnected firm is path dependent since prior alliance relationships impose constraints and offer opportunities for forming new alliances. Although each alliance relies on a short-term contract and is typically short-lived, from the perspective of the interconnected firm, the alliance network is dynamically evolving yet durable. Hence, alliances serve a more critical role than previously assumed in the evolution of the interconnected firm. Interconnected firms can specialize by focusing on their core assets, while simultaneously experimenting and exploring opportunities by dynamically modifying the composition of partners in their alliance network.

The interconnected firm maintains a complex form of interaction with its environment. As illustrated in Figure 1, the interconnected firm discretionally operates through an interface of alliance partners that buffers the legally defined firm from its competitive environment. At the same time, it maintains unmediated interaction with customers, suppliers, and competitors.

The Configuration of the Interconnected Firm

The legal boundaries of the interconnected firm matter less than the boundaries of the nucleus firm and the extended firm. The extended firm confines all resources accessible to the focal firm by virtue of its authority relationships, proprietary asset ownership, and alliance agreements. The

nucleus firm is defined by the proprietary resources that the firm does not share with its alliance partners. Clearly, the scope of the nucleus firm is narrower than the scope of the legally defined firm. The aggregated scope of the legally defined firm and its partners’ resource endowments demarcate the boundaries of the extended firm.

The notions of extended firm and nucleus firm illustrate how artificially defined the legal boundaries of the interconnected firm are. Moreover, both the nucleus firm and the extended firm are porous in the sense that they allow for inbound and outbound flows of resources. The firm can use its network of alliances to accumulate asset stocks essential for gaining competitive advantage. However, the alliance network may also incur losses because of outbound flows, which ultimately lead to the loss of competitive advantage. Another distinction can be made between induced flows and depressed flows. Induced flows are encouraged by both the firm and its partners. They refer to the transfer of intentionally committed resources for the pursuit of agreed upon alliance objectives. These flows are essential for the combination, exchange, and codevelopment of idiosyncratic assets. Depressed flows are those originating outside the scope of alliances and serving for the transfer of resources despite the resistance of the resource owner. Whereas depressed inbound flows can be beneficial to the focal firm, the effect of depressed outbound flows can be destructive. Interconnected firms may seek to depress outbound flows because of the adverse consequences of resource leakage for their long-term competitive standing. As later explained, depressed flows of resources generate spillover rents whereas induced flows of resources serve in the creation of relational rent.

Theoretical Implications For Theories Of The Firm

Traditional perspectives on competitive advantage such as the resource-based view have envisioned firms as independent entities. Consequently, these perspectives have provided only a partial account of competitive advantage in view of the recent growth and significance of alliances. Unfortunately, the rapidly evolving alliance literature has developed its own agenda by focusing on phenomenon-driven research and by drawing from various theories such as the resource-based view, transaction-cost economics, learning and knowledge management, game theory, and social network theories (Osborn & Hagedoorn, 1997). Its emphasis on alliance formation and alliance performance has left a gap between traditional theories of the firm and observations concerning the performance of interconnected firms.

Alliance research has considered the role that alliance networks play in affecting the performance of member firms (Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, 2000). It has focused on the motivation for alliance formation, the identity of firms participating in alliances, the selection of partners, the management of alliances, the determinants of the governance structure or mode of alliance, learning dynamics in alliances, and alliance performance (Gulati, 1998). Interestingly, this research has evolved almost independently from traditional theories of the firm that in turn highlight interfirm competition rather than cooperation.

The gap between traditional theories of the firm and alliance research has left open the question of how interconnected firms gain competitive advantage. Hence, theories such as the resource-based view (Barney, 1991; Wernerfelt, 1984) cannot, in and of themselves, explain how firms that maintain frequent and multiple collaborative relationships with alliance partners gain competitive advantage. Whereas alliance research has provided tools for evaluating value creation and appropriation at the dyad or network level, the integrated contribution of internal and external sources of competitive advantage to firm performance deserves more attention.

The resource-based view is one of the most influential frameworks in strategic management. Rooted in the early work of Penrose (1959), the resource-based view adopted an inward-looking view according to which firms are conceptualized as heterogeneous entities consisting of bundles of idiosyncratic resources. Wernerfelt (1984) and Rumelt (1984) advanced the resource-based view by arguing that the internal development of resources, the nature of these resources, and different methods of employing resources are related to profitability. Hence, firms can develop isolating mechanisms or resource-position barriers that secure economic rents. Dierickx and Cool (1989) provided a more dynamic perspective by arguing that it is not the flow of resources but the accumulated stock of resources that matters and that only those resources that are nontradable, non-imitable, and nonsubstitutable are essential for competitive advantage.

By tying the nature of resources to competitive advantage, the resource-based view suggests that resources lead to Ricardian and quasi-rents. To explicate this phenomenon, Barney (1991) identified value, rarity, imperfect imitability, and imperfect substitutability as resource characteristics that are essential for gaining sustainable competitive advantage. Similarly, Peteraf (1993) elucidated the link between resources and economic rents by identifying resource heterogeneity, limits to competition, and imperfect resource mobility as conditions for competitive advantage. These studies latently assumed that the appropriability of rents requires ownership or at least complete control of the rent-generating resources.

The resource-based view has been recently applied to the study of alliances (e.g., Eisenhardt & Schoonhoven, 1996) but retained the fundamental assumption that resources that confer competitive advantage must be confined by the firm’s boundaries. The resource-based view’s assumption of ownership and control is embedded in most resource definitions. For instance, Wernerfelt (1984) defined resources as “tangible and intangible assets which are tied semi-permanently to the firm [italics added]” (p. 172). Barney (1991) perceived resources as “all assets, capabilities, organizational processes, firm attributes, information, knowledge, etc. controlled by the firm [italics added] that enable the firm to conceive of and implement strategies that improve its efficiency and effectiveness” (p. 101). Finally, Amit and Schoemaker (1993) defined resources as “stocks of available factors that are owned or controlled by the firm [italics added]” (p. 35). This proprietary assumption is not limited to resource definitions but rather concerns the core idea that firms secure rents by imposing resource-position barriers that protect their proprietary resources from imitation and substitution.

The traditional resource-based view has assumed away cooperative interactions via which resources of counterpart firms may enhance firm performance. This proprietary assumption of the resource-based view becomes critical in light of the accumulated evidence on the contribution of network resources to the performance of interconnected firms. Empirical research has found that firms benefit from their alliance partners’ technological resources and reputation and that firm performance and survival depend on the nature of complementary resources of partners (e.g., Afuah, 2000; Rothaermel, 2001; Stuart, 2000). Hence, the resource-based view has failed to acknowledge the direct sharing of resources and the indirect transferability of benefits associated with these resources. The fundamental assumption that firms must own or at least fully control the resources that confer competitive advantage turns out to be incorrect. Ownership and control of resources are not necessary conditions for competitive advantage. A weaker condition of resource accessibility, which establishes the right to utilize and employ resources or enjoy their associated benefits, may suffice.

The proprietary assumption of the resource-based view prevents an accurate evaluation of an interconnected firm’s competitive advantage. Following the rationale of the resource-based view, a firm should be valued based only on the contribution of its internal resources. However, the empirical findings showing abnormal stock market returns following alliance announcements (Anand & Khanna, 2000; Balakrishnan & Koza, 1993; Koh & Venkatraman, 1991; Reuer & Koza, 2000) suggest that firm valuation should be based not only on the internal resources but also on the resource endowments of alliance partners. Hence, needed is an overarching theoretical framework that relates network resources to competitive advantage.

A Resource-Based Theory Of The Interconnected Firm

Following Barney’s (1991) formulation of the resource-based view, we can refer to the broad definition of resources as all types of assets, organizational processes, knowledge, capabilities, and other potential sources of competitive advantage that are owned or controlled by the focal firm. Traditionally, the firm has been said to possess a set of resources that can produce a positive, neutral, or negative impact on its overall competitive advantage. This impact depends on two characteristics of each resource, namely its value and its rarity. In addition, the firm’s competitive advantage is influenced by interactions, combinations, and complementarities across internal resources of the firm. The competitive advantage of the firm can be understood as a function of the combined value and rarity of all firm resources and resource interactions.

Prior to reformulating the resource-based view, it is necessary to examine whether its fundamental resource heterogeneity and imperfect mobility conditions still hold for interconnected firms. Resource heterogeneity requires that not all firms possess the same amount and kinds of resources, whereas imperfect mobility entails resources that are non-tradable or less valuable to other users besides the firm that owns them (Peteraf, 1993). The heterogeneity condition is tied to the conceptualization of firms as independent entities. This condition remains critical, although alliances may contribute to resource homogeneity by facilitating asset flows among interconnected firms. Generally, alliances do not enhance competitive advantage by means of contributing to resource heterogeneity. However, under conditions of pure resource homogeneity, alliances will be formed solely for collusive purposes rather than to gain access to complementary resources. Mergers and acquisitions may be even more effective from alliances for such purpose since they entail unified governance. The imperfect mobility condition is also relevant for interconnected firms. Under perfect mobility, resources can be traded and accessed without forming alliances. However, alliances can serve as means for mobilizing resources that have been traditionally considered immobile. Even when resources cannot be mobilized, alliances enable the transfer of benefits associated with such resources and, thus, weaken the imperfect mobility condition.

Relaxing the proprietary assumption of the resource-based view, we now allow for the resources of partners to affect the competitive advantage of the focal firm. When an alliance is formed, each participating firm endows a subset of its resources to the alliance with the expectation of generating common benefits from the shared resources of both firms. Therefore, each firm possesses a subset of shared resources and a subset of nonshared resources that together form its complete set of resources. Different degrees of convergence may exist between the resources of the interconnected firm and the resources of its partners. When the intersection of shared resource sets, which includes similar resources that both the interconnected firm and its partner own, is substantial, we can identify the alliance with that particular partner as a pooling alliance in which the firm and its partner pool their resources together to achieve a greater scale and enhanced competitive position in their industry. In contrast, when this intersection is diminutive, the alliance can be described as a complementary alliance in which the parties involved seek to achieve synergies by employing distinct resources.

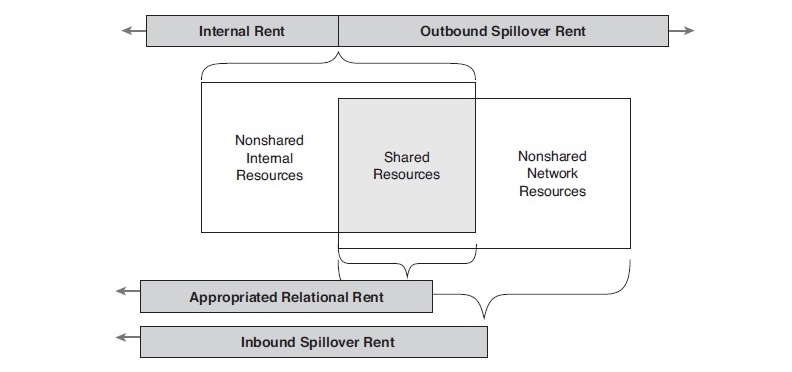

Figure 2 The Competitive Advantage of Interconnected Firms

The resource-based competitive advantage of an interconnected firm can be partitioned into four elements corresponding to four different types of rent: (a) internal rent, (b) appropriated relational rent, (c) inbound spillover rent, and (d) outbound spillover rent. Figure 2 depicts the composition of rents that the interconnected firm extracts from the shared and nonshared network resources associated with its alliances.

Composition Of Rents Extracted By The Focal Firm In An Alliance

Internal Rent

Internal rent refers to the combination of Ricardian rent and quasi-rent derived from the internal resources of the focal firm (Peteraf, 1993). Ricardian rents result from the scarcity of resources, which limits their supply in the short run, whereas quasi-rents encompass the added value that a firm can extract from its specialized resources relative to the value that other firms can extract from similar resources. The traditional resource-based view focuses on internal rents; however, when considering an interconnected firm, we need to incorporate not only the contribution of intrafirm resource complementarities but also that of interfirm resource complementarities. A firm can leverage the value of its own resources by accessing complementary resources of an alliance partner. For instance, the reputation of a start-up biotechnology firm may be enhanced when it forms alliances with prominent partners in the pharmaceutical industry. Unlike relational rents that rely on interfirm complementarities in creating common benefits to alliance partners, internal rents are private benefits enjoyed exclusively by the focal firm. Notably, alliances can produce not only positive synergies but also negative implications for the value of the focal firm’s internal resources. In the former example, the reputation of the pharmaceutical firm may be negatively influenced by the failure of its biotechnology partners’ R&D efforts. Hence, the internal rent derived from a particular internal resource depends on all other internal resources as well as on the network resources embedded in the firm’s alliance network, which produce positive or negative complementarities.

Appropriated Relational Rent

According to the relational view (Dyer & Singh, 1998), relational rent can be defined as a common benefit that accrues to alliance partners through combination, exchange, and codevelopment of idiosyncratic resources. This type of rent cannot be generated individually by either partner and is therefore overlooked by the traditional resource-based view. Relational rents are extracted from relation-specific assets, knowledge-sharing routines, complementary resources, and effective governance mechanisms. Relational rents emerge only from the resources that are intentionally committed and jointly possessed by the alliance partners, and thus involve the shared resources of the focal firm and its partner. The contribution of relational rents to alliance outcomes depends on the total value of these shared resources. Although the relational view does not specify the proportion of relational rents appropriated by each participant in an alliance, unless predetermined, ex post relational rents are rarely distributed equally between the partners. Several factors determine the proportion of relational rents appropriated by the focal firm.

Relative absorptive capacity. Absorptive capacity refers to a firm’s ability to identify, access, assimilate, and exploit external knowledge. Firms often enter alliances with the expectation of learning new knowledge and acquiring external rent-generating resources. However, different firms possess distinctive learning capabilities that may account for the unequal distribution of rents in their alliances. Heterogeneity in absorptive capacities may be ascribed to idiosyncratic resource stocks, path dependencies, and heterogeneous communication channels. Prior studies have shown that a firm’s absorptive capacity accounts for the actual learning from partners and eventually enhances performance (Lane, Salk, & Lyles, 2001). Therefore, the better the absorptive capacity of the focal firm relative to that of its partners, the higher the proportion of relational rents appropriated by the focal firm.

Relative scale and scope of resources. Relational rents accrue due to interfirm resource complementarities and, therefore, are greater for complementary alliances than they are for pooling alliances. The degree of overlap in shared resources of partners varies across alliances. Consider a hypothetical case where the shared resources of the focal firm are a subset of the shared resources of its partner. In this case, the resources that the focal firm can share are internally available to the partner regardless of the alliance. Thus, the partner’s potential benefit from the jointly generated rent is limited relative to that of the focal firm. Similarly, the relative scale of alliance partners’ resources affects the potential for appropriation. A larger resource set of the partner can provide greater benefits to the focal firm insofar as resources are idiosyncratic. In support of this relative scale argument, empirical studies have shown that small firms benefited more than their affluent established partners, even when controlling for firm age (Stuart, 2000). Thus, the smaller the scale and scope of the focal firm’s shared resources relative to those of its partners, the higher the proportion of relational rents appropriated by that firm.

Contractual agreement. Most alliances involve the signing of formal contractual agreements at the time of alliance formation. These contracts provide formal safeguards and determine the distribution of common benefits ex ante. In particular, the payoff structure of a joint venture is often specified in accordance with the partners’ stake in the joint venture. In general, a favorable contract agreement may provide the firm with exclusive access to network resources, may specify a relatively high share of returns on joint activities, may protect the firm’s internal resources from misappropriation by defining the scope of shared resources, and may offer legal remedies that secure the firm’s investments in the alliance.

Relative opportunistic behavior. According to Williamson (1975), contracts are incomplete and cannot specify all future developments. Under such conditions, informal safeguards and trust-building initiatives play an important role in deterring the potential opportunistic behavior of alliance partners. Still, after a contract is signed, opportunistic behavior can result in extraction of a disproportionate share of rents by the opportunistic party (Parkhe, 1993). Hence, the more opportunistic the firm relative to its alliance partner, the higher the proportion of relational rents appropriated by the focal firm. However, the more opportunistic the firms participating in the alliance, the smaller the potential relational rents ex ante, since firms that recognize potential opportunistic behavior of partners tend to limit the scope of collaboration and knowledge transfer which are critical for the creation of relational rent. Thus, opportunistic behavior may temporarily increase a partner’s share of relational rent but eventually reduce the overall relational rent produced by the alliance, lead to termination of that alliance, and reduce the likelihood of future alliance formation with the opportunistic partner.

Relative bargaining power. Bargaining power is defined as the ability to change the terms of agreements favorably, to obtain accommodations from partners, and to influence the outcomes of negotiations. It often depends on the relative stakes of the parties involved in the negotiation and the availability of alternatives. A partner who is less dependent on the outcomes of the alliance and has more alternative contacts relative to the focal firm enjoys a relative bargaining power. Firms rely on their bargaining power at the stage of alliance formation and contract formulation. Yet, due to the incompleteness of contracts and dynamics that affect the relative bargaining power of partners during the course of the alliance, relative bargaining power plays a continuous role in determining the potential for rent appropriation. For instance, Hamel (1991) argued that relative bargaining power complements relative learning skills in determining rent appropriation in alliances. Inkpen and Beamish (1997) demonstrated that alliance partners accumulate knowledge and skills that result in shifts in their relative bargaining power over time. Finally, Khanna, Gulati, and Nohria (1998) posited that an alliance partner’s share of common benefits generated through an alliance depends on its relative bargaining power. Hence, the stronger the bargaining power of the focal firm relative to its alliance partners, the higher the proportion of relational rents appropriated by the firm.

Considering the combined effect of the relation-specific factors mentioned previously, we conclude that at the time of alliance formation the firm’s share of relational rent is likely to be larger under favorable contractual agreements and when the relative scale and scope of its resources is smaller than that of its partners. In addition, the firm’s expected share of relational rent is likely to increase when its partners’ opportunistic behavior is attenuated and when it enjoys a stronger bargaining power relative to its alliance partners. After the alliance is formed, however, the firm’s share of relational rent will be proportional to its relative absorptive capacity, relative opportunistic behavior, and relative bargaining power.

Inbound Spillover Rent

Inbound spillover rent is a form of private benefit that is exclusively derived from network resources because of unintended leakage of both shared and nonshared resources of the alliance partner. Spillover rents are usually associated with horizontal alliances among competitors that seek to internalize the resources of their partners, and thus ultimately improve their competitive position vis-à-vis these partners (Hamel, 1991). When both the firm and its alliance partner pursue such objectives, the parties are said to engage in learning races; however, when only one party holds latent objectives such as targeting the core assets of its partner, it is said to be acting opportunistically. When a firm exploits the alliance for its private benefit outside the agreeable scope of the alliance, it enjoys an unintended spillover of resources with no synergetic value creation. For example, a firm may exploit a technology that was licensed from its partner for a purpose different from that originally intended to or leverage its alliance to access certain resources that were not assigned to the alliance by its partner.

In the case of inbound spillover rent, the competitive advantage of the focal firm depends on several factors. Firm-specific factors determine the capacity of the firm to extract rents from the shared resources of the partner in an involuntary way for unintended purposes. Both firm-specific and partner-specific factors determine the potential for appropriating spillover rents from the nonshared resources of the partner. Because alliances grant the firm access to the shared resources of partners, the leakage of resource benefits is difficult to prevent ex ante using contractual instruments. Coevolving trust and conflict resolution mechanisms can limit such leakage (Kale, Singh, & Perlmutter, 2000); however, the bulk of the appropriation potential hinges upon the good faith of the focal firm. Hence, firm-specific factors including the firm’s opportunistic behavior, bargaining power, and absorptive capacity, affect its ability to accumulate spillover rents from the partner’s shared resources. A superior absorptive capacity may help a firm internalize shared resources as well as identify and access nonshared resources. Its opportunistic behavior may lead to improper use of such resources while a superior bargaining position, in turn, may enable the firm to get away with these actions and, if detected, avoid retaliation by the offended partner.

When considering spillover rents accruing due to non-shared resources, we assume that alliances provide opportunities that range beyond their immediate scope. Hence, the appropriation factors that represent the focal firm’s motivation and capacity to identify and exploit such opportunities are also applicable to the partner’s nonshared resources. However, a partner acknowledging the risk of such unintended appropriation and its adverse consequences for its long-term competitive standing will invest in preventing resource leakage. Partners protect their nonshared resources by utilizing isolating mechanisms such as causal ambiguity, specialized assets, patents, trademarks, and other forms of legal and technical protection (Rumelt, 1984; Wernerfelt, 1984). These isolating mechanisms protect firms from imitation and secure their rent streams. Specifically, these isolating mechanisms prevent the outbound diffusion of rents by limiting the imitability, substitutability, and transferability of strategic resources (Barney, 1991). While the relational view (Dyer & Singh ,1998) acknowledges the role of isolating mechanisms that the firm and its alliance partners jointly employ to protect their shared resources from the external environment, the partners can individually develop other isolating mechanisms to protect their nonshared resources from inbound spillover that benefits the focal firm. Therefore, the stronger the isolating mechanisms employed by its partners, the smaller the inbound spillover rent that the focal firm can extract from the non-shared resources of these partners.

Outbound Spillover Rent

Much as the resources of the alliance partners are subject to spillover rent appropriation, the resources of the focal firm are subject to unintended leakage that benefits its partners. Hence, a symmetric argument can be developed for the impact of outbound spillover rent, which diminishes the competitive advantage of the focal firm as previously discussed. Hence, the more salient the opportunistic behavior of partners and the stronger their bargaining power and absorptive capacity, the greater the firm’s loss ascribed to outbound spillover rent. In turn, the stronger the isolating mechanisms employed by the firm, the smaller the loss associated with outbound spillover rent generated from its nonshared resources.

The overall impact of network resources on the interconnected firm’s competitive advantage can be conceptualized as the combination of the four rent components, namely, internal rent, appropriated relational rent, inbound spillover rent, and outbound spillover rent. Thus, the competitive advantage of an interconnected firm based on the combination of internal resources and network resources is either greater or smaller than the competitive advantage of the same firm being evaluated only on the basis of its internal resources. Firm-specific, partner-specific, and relation-specific factors play a role in determining the type and magnitude of rents extracted from both the internal resources of the focal firm and the network resources of its alliance partners.

Discussion

The proposed framework overcomes a limitation of the traditional resource-based view, which has focused on resources that are owned or internally controlled by a single firm. It incorporates the notion of network resources that play a role in shaping the competitive advantage of interconnected firms. The framework also extends prior research on joint value creation in dyadic alliances (e.g., Dyer & Singh, 1998) by considering unilateral accumulation of spillover rents that produce private benefits. It then suggests that the mechanisms of value creation differ for shared and nonshared resources, and that the value of internal resources is affected by complementarities that span firm boundaries. Overall, engagement in alliances can either benefit or impair a firm’s quest for rents. By extending the resource-based view, this entry sheds light on the conditions under which interconnected firms can gain competitive advantage.

A comprehensive resource-based view of the interconnected firm can be further advanced by analyzing the conditions for sustainability of competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). For instance, causal ambiguity and social complexity may become insufficient for preventing imitation. According to the traditional resource-based view, the limited understanding of how resources contribute to firm performance (i.e., causal ambiguity) and the engagement of multiple actors and multifaceted organizational processes in the deployment and employment of resources (i.e., social complexity) prevents straightforward imitation of resources. However, partners can access resource benefits without obtaining the resources themselves and gain exposure to the path-dependent development of proprietary resources, which thus become less causally ambiguous and socially complex. Moreover, by engaging in proactive learning, partners can internalize the firm’s resources. Consequently, inimitability is tied to the nature of alliance relationships more than to the nature of resources per se. While factors such as contractual safeguards, absorptive capacity, and opportunistic behavior determine the degree of imitation, interconnected firms generally experience greater erosion of rents due to imitation because of the higher level of resource exposure. In addition, imperfect substitutability becomes less relevant to sustainability of competitive advantage in networked environments because partners can gain access to desired resources through alliances, mitigating the need for their substitution. Hence, the capacity of interconnected firms to create and appropriate value depends less on traditional resource-based view conditions and more on the ability of firms to maintain valuable interaction with their partners.

The proposed framework has been developed from the perspective of a focal firm involved in a dyadic alliance but can be easily extended to the case of an interconnected firm embedded in a network structure of multiple simultaneous alliances. This ego-network perspective draws attention to bilateral aspects of the focal firm’s relationships with each of its partners. For example, by examining the degree of similarity, or bilateral fit, between the resources of the firm and those of its partners, alliances can be classified as pooling or complementary alliances for which different value creation mechanisms apply. A tight bilateral fit may benefit the firm by enhancing its ability to understand, learn, and assimilate network resources, thus increasing its share of relational rent as well as the potential for inbound spillover rent. A loose bilateral fit may increase the overall relational rent produced by the firm and its partners due to greater complementarity and synergy in the combination of internal resources and network resources.

Firms with similar resources are often competitors occupying similar market positions, thus a related consideration would involve the emergence of bilateral competition between the firm and its partners. Under conditions of bilateral competition, partners strive to compete away the focal firm’s rents. Bilateral competition modifies the payoff structure of partners in alliances by increasing the ratio of their private benefits to common benefits (Khanna et al., 1998). Hence, it may lead to learning races between the firm and its partners, which can increase inbound and outbound spillover rents at the expense of jointly generated relational rent.

In addition to the implications of interactions between internal resources and network resources, one may consider the implications of interactions among network resources. In this regard, it is possible to distinguish a homogeneous network in which the resource sets of partners are similar from a heterogeneous network in which alliance partners own different resource sets. A homogeneous network is characterized by a tight multilateral fit that may enhance the capacity of the focal firm to appropriate rents based on accumulated experience with similar partners, more efficient governance mechanisms, and enhanced bargaining position derived from reduced dependence on each partner. In contrast, the rent-generating potential of a heterogeneous network (loose multilateral fit) rests in synergies enabled by complementary resources, reduced technological risk, increased growth potential, and greater opportunities for innovation. In the same vein, one may consider the level of multilateral competition that describes the degree of competition among partners in the firm’s alliance network. Alliance partners who join the firm’s network would often act to preempt their competitors and lock them out of the network in order to secure superior access to resources. In addition, the focal firm would extend its alliance network only to the extent that new partners offer added value or synergies. Hence, the focal firm’s capacity to appropriate rent from network resources may depend on the structure of its network. Further research is needed in order to explore the performance implications of bilateral and multilateral fit as well as bilateral and multilateral competition. These aspects have received limited attention in prior research.

Future research may extend the proposed framework in several ways. First, it may evaluate the impact of network structure (e.g., the density of ties in the firm’s ego-network) relative to relational aspects such as trust building, knowledge sharing, bargaining power, and learning. Second, it may acknowledge the fact that different appropriation processes require dissimilar spans of time. For instance, the benefits of complementarities that enhance the value of internal resources may be available at the outset of the alliance, but relational rents are accumulated gradually as a result of continuous collaboration. The benefits associated with spillover rents may consume even more time because firms need to bypass their partners’ isolating mechanisms. Third, future research may be able to consider not only the impact of direct ties but also the influence of indirect ties. For example, a firm may seek to ally with a certain partner in order to indirectly access the resources possessed by that partner’s partners. From the perspective advocated in this entry, resource-based rents are transferable to some extent; thus, firms may be able to access network resources through intermediaries. Finally, the proposed framework should be empirically corroborated to further advance understanding of the value of network resources.

Conclusion

At the turn of the 21st century, alliances have emerged as a primary vehicle for conducting economic transactions. Once conceived of as independent entities, firms are now considered interconnected in the sense that they engage in multiple alliances with counterpart firms. This phenomenon necessitates a new theory of the firm that incorporates simultaneous competition and collaboration as drivers of value creation and appropriation. In particular, the traditional resource-based view has advocated isolation of strategic assets whereas the alliance literature has promoted sharing of such resources. This entry bridges the conceptual gap between these perspectives by distinguishing shared resources from nonshared resources in alliances and by specifying the various types of rents that firms can extract from their multiple alliances. The implications of this framework are far reaching. Managers need to pay attention not only to the value of resources nurtured by their own firms but also to the resources possessed by their firms’ partners. They must evaluate the value of network resources as well as the value of potential combinations of network resources and internal resources. They must collaborate to create value and compete to appropriate their relative share of that value. They must look beyond the immediate scope of alliances and seek to leverage network resources while finding the right balance between resource sharing and the protection of proprietary assets. In conclusion, management in the 21st century has become more challenging and complex yet offers greater prospects to those willing and capable of exploring the nature of interconnected firms.

Bibliography:

- Afuah, A. (2000). How much your coopetitors’ capabilities matter in the face of technological change [Special issue]. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 387-404.

- Ahuja, G. (2000). The duality of collaboration: Inducements and opportunities in the formation of interfirm linkages [Special issue]. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 317-343.

- Amit, R., S Schoemaker, P. (1993). Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14, ЗЗ-4б.

- Anand, B. N., S Khanna, T. (2000). Do firms learn to create value? The case of alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 295-317.

- Balakrishnan, S., & Koza, M. P. (1993). Information asymmetry, adverse selection and joint-ventures. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 20(1), 99-117.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

- Baum, J. A. C., Calabrese, T., & Silverman, B. S. (2000). Don’t go it alone: Alliance network composition and startups’ performance in Canadian biotechnology. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 267-294.

- De Wever, S., Martens, R., & Vandenbempt, K. (2005). The impact of trust on strategic resource acquisition through interorganizational networks: Towards a conceptual model. Human Relations, 58(12), 1523-1543.

- Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. (1989). Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management Science, 35, 1504-1513.

- Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategies and sources of interorganizational competitive ad-vantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 660-679.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Schoonhoven, C. B. (1996). Resource-based view of strategic alliance formation: Strategic and social effects in entrepreneurial firms. Organization Science, 7(2), 136-150.

- Greve, H. R. (2005). Interorganizational learning and heterogeneous social structure. Organization Studies, 26(7), 1025-1047.

- Gulati, R. (1995). Social structure and alliance formation patterns: A longitudinal analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(4), 619-652.

- Gulati, R. (1998). Alliances and networks. Strategic Management Journal, 19(4), 293-317.

- Gulati, R. (1999). Network location and learning: The influence of network resources and firm capabilities on alliance formation. Strategic Management Journal, 20(5), 397-420.

- Gulati, R. (2007). Managing network resources: Alliances, affiliations, and other relational assets. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gulati, R., Nohria, N., & Zaheer, A. (2000). Strategic networks [Special issue]. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 203-215.

- Hagedoorn, J. (1993). Understanding the rationale of strategic technology partnering. Strategic Management Journal, 14(5), 371-385.

- Hamel, G. (1991, Summer). Competition for competence and interpartner learning within international strategic alliances [Special issue]. Strategic Management Journal, 12, 83-103.

- Inkpen, A. C., & Beamish, P. W. (1997). Knowledge, bargaining power, and the instability of international joint ventures. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 177-202.

- Kale, P., Singh, H., & Perlmutter, H. (2000). Learning and protection of proprietary assets in strategic alliances: Building relational capital. Strategic Management Journal, 21(3), 217-237.

- Khanna, T., Gulati, R., & Nohria, N. (1998). The dynamics of learning alliances: Competition, cooperation, and relative scope. Strategic Management Journal, 19(3), 193-210.

- Koh, J., & Venkatraman, N. (1991). Joint venture formations and stock market reactions: An assessment in the Information Technology sector. Academy of Management Journal, 34(4), 869-892.

- Lane, P. J., Salk, J. E., & Lyles, M. A. (2001). Absorptive capacity, learning, and performance in international joint ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 1139-1161.

- Lavie, D. (2QQ4). The interconnected firm: Evolution, strategy, and performance. Unpublished doctoral disseration, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

- Lavie, D. (2QQ6). The competitive advantage of interconnected firms: An extension of the resource-based view. Academy of Management Review, 31(3), 638-658.

- Lavie, D. (in press). Alliance portfolios and firm performance: A study of value creation and appropriation in the U.S. software industry. Strategic Management Journal.

- Osborn, R. N., & Hagedoorn, J. (1997). The institutionalization and evolutionary dynamics of interorganizational alliances and networks. Academy of Management Journal, 40(2), 261-278.

- Parkhe, A. (1993). Strategic alliance structuring: A game theoretic and transaction cost examination of interfirm cooperation. Academy of Management Journal, 36(4), 794-829.

- Penrose, E. T. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. New York: Wiley.

- Peteraf, M. A. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14(3), 179-191.

- Powell, W. W., Koput, K. W., & Smith-Doerr, L. (1996). Interorganizational collaboration and the locus of innovation: Networks of learning in biotechnology. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(1), 116-145.

- Reuer, J. J., & Koza, M. P. (2QQQ). Asymmetric information and joint venture performance: theory and evidence for domestic and international joint ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 81-88.

- Rothaermel, F. T. (2QQ1). Incumbent’s advantage through exploiting complementary assets via interfirm cooperation. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 687-699.

- Rumelt, R. P. (1984). Towards a strategic theory of the firm. In R. B. Lamb (Ed.), Competitive strategic management (Vol. 26, pp. 556-570). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Stuart, T. E. (2QQQ). Interorganizational alliances and the performance of firms: A study of growth and innovation rates in a high-technology industry. Strategic Management Journal, 21(8), 719-811.

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171-180.

- Williamson, O. E. (1975). Markets and hierarchies, analysis and antitrust implications: A study in the economics of internal organization. New York: The Free Press.

- White, S., & Lui, S. S. Y. (2QQ5). Distinguishing costs of cooperation and control in alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 26(1Q), 913-932.

- Zajac, E. J., & Olsen, C. P. (1993). From transaction cost to transaction value analysis: Implications for the study of interorganizational strategies. Journal of Management Studies, 30, 131-145.