View sample Human Resorce Management Research Paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a management research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The second decade of the 21st century provides a fresh opportunity to think about kinds of possible management. In this regard, the area of human resource management (HRM) has become even more important to business, policymaking, and nations, including in the economically dynamic Asia-Pacific region. Most of the Asian economies had rapid growth rates for the past two to three decades, although uneven from year to year, and were then hit by the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. Interestingly, now the very same HRM practices formerly seen as paragons (and taken as “best practices” by some), partly responsible for such success and emulated and exported around the world (e.g., via “Japanization”), have become seen by some as problematic. In such a milieu, some Asian companies began looking to other countries for exemplars of HRM to import. Such issues raise important questions: Are there any HRM best practices? Can they be transferred? The search for best practice in comparative management research relates to the debate on convergence toward common practices that apply to all countries versus continuing or even growing divergence practices.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Many Asian economies do share common features, for example, fast economic growth, social development, surge in foreign direct investment (FDI), multinational companies (MNCs), and so forth. These factors can provide a strong momentum to practice transference to Asia. Despite common features across the region, however, their specific institutional forms vary from one country to another (Hamilton, 1995) and act as serious constraints on transfer and, hence, convergence and promote continuing distinctiveness or even increasing divergence. Besides, since the transfer of practices occurs in a multifaceted context (between headquarters and overseas subsidiaries; Briscoe, 1995; Dowling, Schuler, & Welch, 1994) and at different stages (from preinstitutionalization to full implementation; Tolbert & Zucker 1996), the issue of transferability becomes more about “degree,” less about “all or nothing,” and more about “what” practices (Pudelko, 2005) and to what extent.

The aim of this research paper is to examine if there are best practices in HRM that can be transferable to Asia and whether this indicates convergence in HRM. Key HRM practices and policies of employment, rewards, and development will be used to examine these issues. The structure of the rest of the research paper follows. The next section introduces the theoretical debates associated with the possible reasons for transfer, what has been transferred, and how it has happened. The research paper then provides methods to examine the transfer issue and a basis for comparison across countries, along with some general applications and comparisons. Finally, the research paper draws together the propositions and outlines some possible future directions.

Theory

Classical management thought and more recent variants assume that a set of “best” management practices, as in HRM, can be valid in all circumstances and help organizations perform better and obtain sustainable competitive advantage (Becker & Gerhart, 1996; Huselid, 1995; Lado & Wilson, 1994).

What Are “Best Practices”?

This idea can be traced back for some considerable time. For instance, Taylor’s (1911) earlier “scientific management” implied that there was “one best way” of managing. We can recall, as do Boxall and Purcell (2003), that studies of individual best practices within the major HR categories of selection, training, and appraisal have a very long tradition, such as when much effort was put into improving selection practices for officers and training for production workers during both World Wars. In the 1960s, best practice would have been taken as those associated with an American model (Kerr, Dunlop, Harbison, & Meyers, 1962) and in the 1980s, a Japanese one (Oliver & Wilkinson, 1992). Such universalistic views continued to appear and returned in various forms, as belief held that practices could be applicable across countries. Thus, “in best practice thinking, a universal prescription is preferred” (Boxall & Purcell, 2003, p. 61).

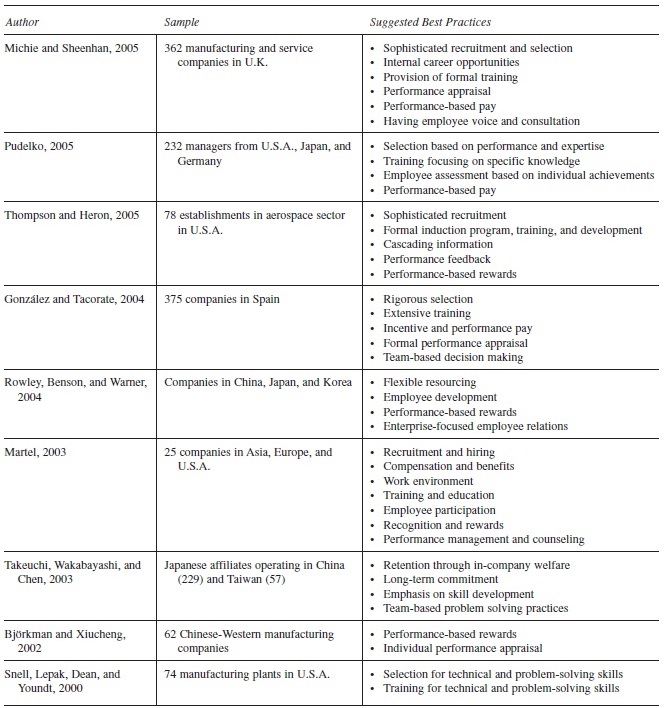

Table 1 Selective Research on Best HRM Practices by Author

One strand in the area is the development of lists of best practices. Among the most famous are those of Pfeffer (1994, 1998), whose list of 16 (of relevance here included employment security, selectivity in selection, promotion from within, high pay, incentive pay, wage compression, and training and skill development), later narrowed to seven (of relevance here were employment security, selective and sophisticated hiring, high compensation contingent on performance, extensive training and development, reduction of status differentials, and sharing information self-managed teams/teamworking; see overviews of other lists in Boxall & Purcell, 2003; Redman & Wilkinson, 2006). Some take a broad definition that best practices are those that can add value to the business. Others are more specific and pinpoint certain practices in particular situations. For others, they are those present in successful and/or high-profile companies. Indeed, research on best practices including collective issues of work organization and employee voice is rare (Boxall & Purcell, 2003).

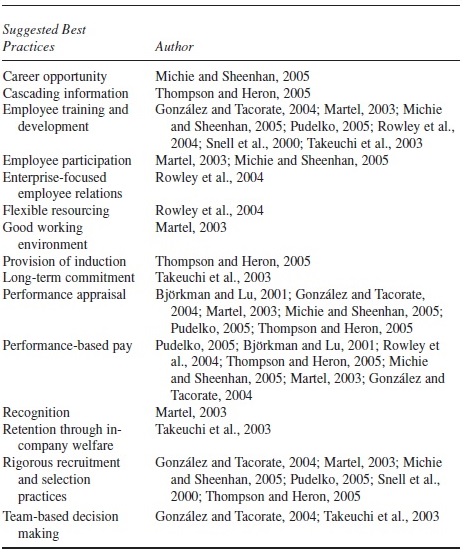

Recent studies (Tables 1 sorted by author and 2 by practice) typically include comprehensive employee recruitment procedures, incentive compensation, performance management systems, extensive employee training, and so forth.

Some unresolved issues and questions muddy what at first sight seems simple and clear. The whole notion of best practices raises several questions (Bae & Rowley, 2001; Thang, Rowley, Troung, & Warner, 2007). There may be quite agreement on what “bad practices” are (Boxall & Purcell, 2003), but there is no consensus on what “best practices” are. Their conceptualization, interpretation, and measurement remain subjective and variable among people, countries, and time. Therefore, while some commonalities exist across various lists, there is less of a consensus, and lists vary over time, location, and researcher. The varied use of terms and concepts such as “work systems” for high “performance,” “commitment,” “involvement,” and so on create more uncertainty and opaqueness. Thus, we could quickly agree on and coalesce around sensible HR practices, but “things tend to get out of hand, however, when writers aggregate their favorite practices—and their implicit assumptions—into more ambitious lists and offer them to the world at large. Such models generally overlook the way that context affects the shape of the HR practices that emerge in a firm over time” (Boxall & Purcell, 2003, p. 68). In addition to the identification and definition are the following issues. First, we can question the extent to which all organizations might wish, or be able, to implement best practices due to costs and/or sectors in business strategy and location. Thus, “lower value-added approaches may prove highly profitable in specific industries and locales” (Redman & Wilkinson, 2006, p. 266), and consideration of cost-effectiveness is important (Boxall & Purcell, 2003). Second, we need to ask, For whom is this best practice: organizations, shareholders, senior executives, managers, or employees? Much literature fudges this (Boxall & Purcell, 2003) or assumes “for all” (Redman & Wilkinson, 2006). Yet, such unitary perspectives are not common throughout the world (Rowley & Warner, 2007), and organizations are composed ofa plural and divergent range of interests. Third, to whom are these practices applied, and is a minimum coverage needed of such groups and the organization’s total HR? Fourth, are all best practices equally important, and are single practices or “bundles” of practices needed? If such groups are needed, what about the conflictual tendencies and contradictions best practices can generate? Thus, there may be incompatibility between practices. One example is Pfeffer’s (1994) list which had incentive pay, high wages, and wage compression as three best practices in the rewards area. Are these practices actually likely to occur together? The furor in the media over excessive chief executive rewards and the vast gap in comparison to the pay of other employees, especially in American companies, shows that this is unlikely. Fifth, there has been only limited actual (as opposed to prescriptive or normative) diffusion and take-up, both at individual practice or HRM system level (see Boxall & Purcell).

Table 2 Selective Research on Best HRM Practices by Practice

An important issue is about global transference of such practices. The theory of take-up of Western practices derives in part from assumptions that they are somehow superior (Bae & Rowley, 2001). Economic dominance has led to diffusion of theory and organizational practice from the United States. While some researchers (see, e.g., Pudelko, 2005) believe that managerial practices in other countries are deviations from the American model, others (see, e.g., Gonzalez & Tacorate, 2004) argue that competition between dominant countries means that no single “best” model persists. Rather, countries use their unique cultural and institutional frameworks to create distinct national competitive advantage, potentially militating against the diffusion of best practices. Cultural theorists concur that if practices and cultural values are compatible, it will be easier for employees to understand and internalize practices (Rowley & Benson, 2002, 2004). Historical contexts, unique cultural values, and institutional variations all retain their influence over organizations and local workforces in Asian economies and may foster the development of a unique Asian management model (Rowley, Benson, & Warner, 2004).

In summary, there is debate about best practices in terms of precisely what they are and what their universal application is. “Beyond a certain level of obviously sensible practices, managers start to think about their unique context. This naturally engenders diversity rather than uniformity in HRM” (Boxall & Purcell, 2003, p. 63).

Why Transfer Occurs

Why have transfers of HRM occurred? According to some theorists (see, e.g., Kerr et al. 1962), worldwide socioeconomic and political forces create tendencies for countries, and by implication their management practices, to become more similar. Globalization, internationalization, and technological advancement further push national systems toward uniformity as copying and transferring of the practices are encouraged. One implication of this is that HRM systems of different countries will grow more similar and converge (Rowley et al. 2004).

Kerr et al. (1962) observed that the organizational and institutional patterns of societies can converge, suggesting that industrialism generated socioeconomic, political, and technological imperatives that molded the development of national institutional frameworks toward a common pattern or convergence. Furthermore, globalization and, subsequently, the consequences of the Asian Crisis, which forced firms to adopt different practices to be competitive and survive, can fuel transfers. HRM change was seen as a suitable strategy for corporate renewal. MNCs exported new practices to their local subsidiaries and became the target of benchmarking by indigenous firms. Edwards and Ferner (2002) argued that MNCs can be a principal channel for transferring knowledge across borders as they can adopt a proactive approach to identify and propagate best practice, while learning about local environments and regulations. The impact of such drivers, however, has not been uniform in the region and mixed with economic, political, and cultural forces.

Technological developments also may aid transfers. This includes Internet applications in business. The extensive use of the Internet is revolutionizing the nature, conduct, and organization of business. Some companies have slowly utilized technologies related to improving HR functions, for example, e-training, online job posting, e-learning, and so forth.

Proposition 1: Some forces and trends are generating a transfer of Western HRM best practices to Asia-Pacific economies.

Institutional theory and imitation forces play another role in transfer. Three mechanisms of institutional “isomorphic” change (“coercive” isomorphism to gain legitimacy, “mimetic” isomorphism to avoid uncertainty, and “normative” isomorphism from professionalization) are suggested (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Therefore, practices may be transferred not simply because of their effectiveness (or because they are “best”) but due to social forces to gain legitimacy (McKinley, Senchez, & Schick, 1995). The ideological shifts from communism to market socialism in the People’s Republic of China (henceforth, China) and Vietnam and implementation of economic reforms in Malaysia and elsewhere in Asia have created a new institutional environment and exerted pressure for firms to adopt institutional rules. Local companies start to conform to social constraints and accept other practices. For instance, in China the accession to World Trade Organization (WTO) pressurized state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to imitate the practices of Western MNCs to demonstrate that they are in step with international markets. The popularity of overseas business schools in many Asian countries also promotes transfers and ideas of managerial practices seen as prevalent in Western countries. The implicit assumption suggests that best practice effects are not national or company specific, but rather universal and transferable.

There is, however, a paradox. Can Asian countries “benchmark” HRM practices to become competitive? According to resource-based theorists (see, e.g., Lado & Wilson, 1994), unique (i.e., rare and inimitable) HRM practices cannot be copied or transferred. HR elements are path dependent and made up of policies and practices developed over time (Becker & Gerhart, 1996). Therefore, there are limits on organizations converging toward other companies’ socially complex elements and practices. Similarly, contingency theorists argue that organizations, people, and situations can vary and change over time according to the external environment (see, e.g., Jackson, Schuler, & Rivero 1989), to the firms’ stage of international evolution (see, e.g., Adler & Ghadar, 1990), or to tally with business strategy (see, e.g., Becker & Gerhart, 1996). Thus, the right mix of transferable HRM depends on a complex variety of critical environmental and internal contingencies. In sum, a paradox exists here because while imitating practices may lead to competitive advantage, it is hard to copy practices implicitly embedded in organizations.

Proposition 2: Institutional forces and external pressures generate HRM practices unique to the Asia-Pacific region and different from Western best practices.

Transfer Issues

The transferability of HRM can occur in multiple dimensions. First, MNCs can use an ethnocentric strategy to transfer their headquarters’ practices to their overseas subsidiaries, employ a polycentric strategy to totally adapt to local situations, or adopt a geocentric strategy to balance both global integration and local adaptation (Caligiuri & Stroh, 1995; Dowling, 1989). Second, transfer of management ideas can be viewed from various theoretical perspectives, namely rational, psychodynamic, dramaturgical, political, cultural, and institutional approaches (Sturdy, 2004). Third, the transfer process can be at different stages: preinstitutionalization (where there are few adopters and a limited knowledge about practices), semi-institutionalization (where practices are fairly diffused and have gained some acceptance), and full institutionalization (where practices have become “taken for granted”; Tolbert & Zucker, 1996). Thus, adoption of a transferred practice can occur at various degrees. At the surface level is implementation, whereby formal rules are followed by external and objective behaviors, but at the deeper level is internalization, whereby employees have commitment to, and ownership of, the practice (Kostova, 1999).

Another question relates to level: where and how much transfer do we need before we conclude transfer has occurred? From a system point of view, an HRM system includes architecture (guiding principles and basic assumptions), policy alternatives (mix of policies), and practice process (implementation and techniques; Becker & Gerhart, 1996; Rowley & Benson, 2002). Does transfer occur at all levels? Or does it occur at some levels? If transfer has occurred, over what time span and at what speed has it taken place? These are key analytical and research issues and questions in this area.

The transferability of HRM then becomes a matter of level and degree. For example, at the practice level, people may resist guiding principles due to local customs or lack of training, or operational practices may not be built into policy owing to external constraints. Adoption of HRM in Asia appears strongest at the level of practice and weaker at the policy or architectural levels (Rowley & Benson, 2002).

Yet, even at HR practice level, embedded customs and traditions constrain transfers. Other factors, including stage of economic development and level of technology, can hold back transfers. For instance, the rate of acceptance of new knowledge is slow and cautious in the region. Countries like China continue to rely on traditional ways to keep personnel records and administer welfare benefits (Chow, 2004). The degree to which local companies implant new practices is constrained by organizational inertia (Warner, 2000), especially their cultural and institutional heritages.

HRM in the Asia-Pacific region is often different from many Western practices. It is, therefore, worthwhile to further investigate best practice transfer in the Asian context.

Methods

HRM is crucial for organizations and economies to achieve success (see, e.g., Barney, 1991; Pfeffer, 1994). Yet, despite this view of HRM’s value as a specialized and specific business function, it is a relatively new area of interest in Asia. It is hard to come up with a common method to assess all Asian countries as a whole on the application of HRM best practices. The complication stems not only from those elucidated earlier, but also from the fact that it is probably too simplistic to assume a homogeneous bloc of countries in this region.

Not a Single Homogenous Bloc

In fact, the region comprises areas of vast diversities (even within national boundaries) in terms of demographic characteristics, economic development, social background, and cultural values. It would not be surprising that rate of new knowledge adoption and the degree of foreign influence are not the same across the region. The region consists of a wide range of countries and national systems. Geographic and demographic factors feature strongly. The economies range from those with very large populations like China and Indonesia to those with a few million inhabitants like Hong Kong and Singapore. Countries also have differing birthrates and age profiles. This population variable can mold the nature of the labor market and the workforce. Unemployment rates have also been uneven, with some economies doing better than others as growth created varied demands for labor. The range and variety of the working population in the region are varied.

Economically, most of the Asian countries had rapid growth rates over the last two decades, although variable from year to year. Many people doubt whether previous Asian economic growth can be sustained. In addition, governments play dominant roles in the region. Southeast Asian nations such as Vietnam and Malaysia experienced heavy state intervention including tight regulation and control of labor markets and trade unions. This shows that each country has taken a different development path and, hence, emerged with a distinct pattern of industrial structure. Deep-rooted differences among Asian economies mean management and HRM practices may vary as well.

Different National Cultures

Another complication in HRM practice transfer is multiple national cultural values (Rowley, 1998). The debate of “culture-free” and “culture-specific” relates to the extent that localities retain power to influence management practice or are overridden by transferred practices. It is concerned with the degree to which businesses take account of the particular contexts in which they operate and from which they evolved.

Prima facie, the whole region seems to share some common cultural values, hence the often-used phrase “Asian values.” Yet, Asians’ religious and philosophical beliefs vary and include Confucianism, Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, and Taoist traditions. Sinha and Kao (1988) argued that Asian productivity and growth is widely attributed to both traditional management styles and work attitudes rooted in Confucian social values, familism, and so on, not found in Euro-American contexts. After all, best HRM practices ought to be the ones best adapted to cultural and national differences.

Various Degrees of Foreign Impact

Influence from foreign countries is also felt differently across the Asian economies. One impact comes from experiences of earlier colonization and occupation from a range of countries (Britain, France, Netherlands, Spain, Japan, and United States) and the inflow of MNCs and FDI. Foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) can bring into the region not only the latest equipment and technology, but also management expertise and HRM. For example, new HRM systems and technology are found in the FIE-dominated, export-oriented industrialization (EOI) sector, as in Malaysia and East Asia (Rasiah, 2004).

Application

Questions arise as to whether theories and frameworks developed in the West apply in different contexts. To apply the HRM concept in other countries it is important to understand its meanings. Legge (1989) and others explain the term HRM by encapsulating its various differences from personnel management (PM): (a) whereas HRM concentrates on the management of teams, PM focuses on the control of subordinates; (b) line managers play a key role in HRM in coordinating resources, but they do not do so under PM; (c) the management of organizational culture is an important aspect of HRM but not PM; and (d) HRM is a more strategic task than PM.

Furthermore, HRM cannot be divorced from its institutional context. HRM (and best practices) are criticized as Anglo-American concepts and culturally bound (Easterby-Smith, Malina, & Lu, 1995). Whether they can, or even should, be replicated in the Asian context is a matter of opinion. Warner (1995) has cast doubt on applying the term HRM in Asia given the cultural differences that exist with the West. He used China as an example to argue that Western notions of HRM were not present in enterprises. The roles of PM were far from the concept of HRM as understood in Western theory. HRM with “Chinese characteristics” (Warner, 1995, p. 145) may be a more appropriate term to use.

Attempts to compare changes of HRM practices in different Asian economies often raise the question of what to include. The literature provides no clear list or model of HRM practices, and different researchers have their own lists. For instance, Rowley et al. (2004) used the common practice categories of recruitment and selection, training and development, and rewards and employment relations to compare HRM across three Asian countries (Korea, Japan, and China). Bjorkman and Xiucheng (2002) used rigorous recruitment and selection processes, extensive training, and performance contingent compensation systems.

Even if an agreement could be reached upon what to cover in the Asian context, it is difficult to encompass all HRM elements in a single, short research paper. Therefore, key areas where potential developments and changes can be reflected over time must be chosen. The approach taken here is to search for HRM areas where changes have occurred and where it is possible to observe transfer and adoption of best practices.

Huselid (1995) grouped HRM practices into dimensions that augment people skills, motivate employees, and organize workforces. Therefore, the best HRM practices are those that concern employment, rewards, and development. Some studies (see, e.g., Lado & Wilson, 1994; Pfeffer, 1994) show that companies utilizing their human capital as their unique advantage over others place top priority on people recruitment, reward, and development. Accordingly, three HRM practices are identified as best practices: employment flexibility, performance-based rewards, and employee development investment. These commonly appear on various best practice lists (see earlier discussion). These HRM practices will be discussed using examples and evidence from a range of Asian economies including economic superpowers, both existing (Japan) and emerging (China), “little dragons” (Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan), and developing nations (Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam). While not totally comprehensive of the Asia-Pacific region, these countries do encompass the major economic and population centers.

HRM Best Practices

Employment Flexibility

Ideas of sophisticated recruitment and selection (Pfeffer, 1994) slightly metamorphosed into selective and sophisticated hiring (Pfeffer, 1998). Also, Pfeffer (1994) earlier had put forth promotion from within.

Seen as a Western HRM prescription, employment flexibility allowed for easier matching of labor to demand than was possible with former Asian lifetime employment models. Employment flexibility has various dimensions to it—not only numerical (dealt with below) but also financial and functional. The numerical flexibility in employment arrangements, for instance use of nonregular employees (i.e., part-time workers, casual workers, temporary employees, etc.), allows the organization to increase or decrease employment quickly in line with fluctuations in business demand without the costly overheads associated with full-time, permanent employees.

Contradiction and tension, however, exist between security and flexibility (numerical). For people like Pfeffer (1998), employment security was fundamental and underpinned other best practices. This is because HR outputs such as increased performance and motivation require some expectation of employment stability and concern for future careers and links to notions of the “psychological contract,” “mutuality,” “reciprocity,” “partnership,” and so on. This presents a dichotomy in the treatment of HR as critical assets for the long-term success of organizations and not as variable costs (Marchington & Wilkinson, 2005).

Performance-Based Rewards

Expectancy theory suggests that individuals are motivated to perform if they know that their extra performance is recognized and rewarded (Vroom, 1964). Consequently, companies using performance-based pay can expect improvements. Performance-based pay can link rewards to the amount of products employees produced. As such, attraction, retention, productivity, quality, participation, and morale may improve. Yet, for best practice gurus such as Pfeffer (1998), rewards had twin elements and needed to be not only performance-related but also higher than average.

Employee Development Investment

Extensive and quality (with focus and delivery) development is one of the most widely quoted aspects of best practice HRM (Marchington & Wilkinson, 2005). For several authors, training and development play a crucial role in international competitiveness (see, e.g., Finegold & Soskice, 1988). Investment in employee development is valuable to meet the needs of economies and organizations with increasing demands for higher levels of skills. Besides, training is often regarded as a benefit offered by organizations to reinforce employee dependence on the organization. Completion of training can lead to promotion. As such, training plays an important role in social mobility and acceptance. Thus, substantial and continuous investment in employee development can be seen as a best practice.

What type of development should companies invest in? And, for whom in the companies should it be offered? Does it need to be job specific or general?

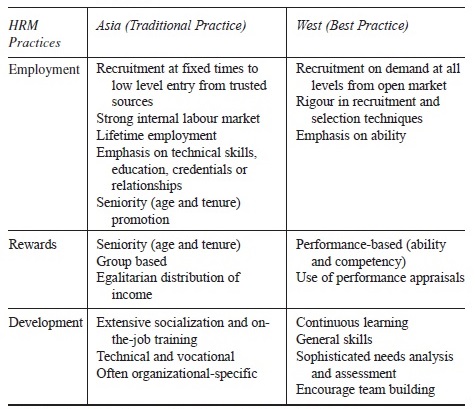

These three best practices are very different from traditional practices predominately used in Asia (i.e., lifetime employment, seniority-based pay, and organizational specific/ technical skills training) (see Table 3).

Table 3 Comparison Between Asia Traditional Practices and West Best Practices

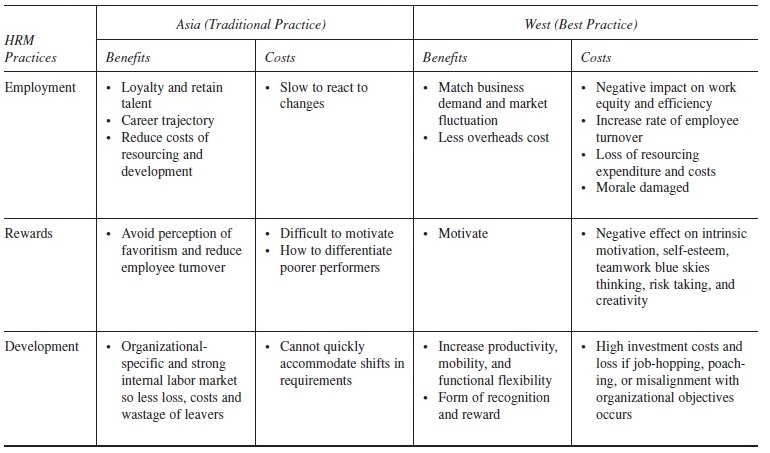

Table 4 Benefits and Costs of Asia Traditional Practices and West Best Practices

Issues

The analysis so far, however, does not mean that these three best practices are always better than traditional practices. These best practices have downsides, and Table 4 compares the benefits and costs. For instance, inter alia, employment flexibility creating an increasing proportion of nonregular employees has negative implications for work equity, efficiency, and morale and may boost employee turnover and be at the cost training budgets. Pay-for-performance can have destructive effects on intrinsic motivation, self-esteem, teamwork, “blue skies” thinking and risk taking, and creativity. A high level of training investment may generate negative returns if trainees job-hop, are “poached,” or are misaligned with organizational objectives. In addition, changes pressurize HR departments and practitioners to manage increased diversity and utilize different systems to cope with multiple employees’ needs, which may involve the operationalization of such traditionally costly and alien concepts and practices as rigorous performance assessments and meetings and even 360-degree appraisals.

Besides, there is the issue of compatibility of best practices. The resource-based view stresses the importance of complementary resources in combination or bundled to enable a firm to realize its full competitive advantage (Barney, 1995). Accordingly, best practices are most effective when used in combination with one another. An underlying theme is that firms should create a high degree of internal consistency, or “fit,” or synergy among their HR practices (Michie & Sheehan, 2005). This idea that a bundle of practices may be more than the sum of the parts appears in the discussions of external fit, configurations, holistic approach, and so forth.

Comparison

A discussion of the three HRM best practices using examples of Asia-Pacific economies follows.

Employment Flexibility

Companies in different countries have taken different approaches to fit in with their institutional context. Some argue that national cultures affect hiring practices in various countries (Yuen & Kee, 1993). The restructuring of Asian economies due to globalization and industrialization, however, has led to a number of consequences including factory relocations, cutbacks and lay-offs, unemployment and subsequent retraining, and so forth (Warner, 2003) because businesses are looking for changes and adjustments in workplace HRM practices. After the Asian Crisis, companies realized that seniority-based systems and lifetime employment were costly; they needed flexibility in headcount adjustments to enable quicker responses to market fluctuation and competition.

Classic lifetime employment was found is Japan. In recent years, however, a new group of workers known as “job-hoppers” has evolved. Opposed to seeking out a reliable company after graduating from university and staying until retirement, some younger Japanese have chosen to change jobs every few years (Benson & Debroux, 1997). According to a survey in Japan Statistics (2002), 18% of high-school graduates left their first job within a year. In addition, large companies employ flexible employment policies that relied on nonregular workers. This indicates change in traditional Japanese employment practice.

Lifetime employment is also changing in Korea. In 1999, the terms of the post-1997 Crisis International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout forced the government to legalize layoffs, weakening this traditional concept. The general direction has moved away from lifetime employment toward easier employment adjustments. Consequently, permanent, full-time workers markedly declined and were replaced by part-time or nonregular employees (Rowley & Bae, 2004).

Nevertheless, the type of organization remains important. For example, public sector organizations, SOEs in countries like China and Vietnam, and government-linked firms in countries like Malaysia all retain greater lifetime employment.

Performance-Based Rewards

Some Asian managers believe that performance-based rewards of various forms (commissions, bonuses, profitsharing, share options, etc.) are Western best practices because they tie rewards to job performance as opposed to traditional Asian “seniorityism” of compensation based on age and/or tenure. Companies offering such plans try to be more attractive than their competitors in recruiting and retaining the best talent. The earlier Asian Crisis and global competition, however, have made companies more conservative in making increases to all employees and more likely to take the form of performance-based incentives. The spread of Western compensation systems and performance appraisals through FIEs in China has been significant since the 1990s (Bjorkman & Xiucheng, 2002). Variable compensation in the form of stock options, employee shareholding, and the like have also seemingly spread and exerted influence over Asian compensation schemes.

We can, however, question the spread of such schemes across both sectoral types and with organizational hierarchies. Also, instilling a performance-based culture, a shift in HRM system architecture, demands consistent policy mixes and practices. Indeed, some companies are reverting to seniority-based systems as companies struggle to effectively assess work and productivity. According to one report, over 75% of Japanese companies that had introduced performance-based pay systems experienced difficulties in managing them (Japan Institute of Labor Policy and Training [JILPT] 2004). The major difficulties were (a) lack of a performance rating system to assess performance, (b) insufficient training for managers to make them commit to the system, and (c) feelings of a lack of job security and company loyalty. It seems that the transfer of a practice is one thing, but making it effective is another. If the transfer is not followed by a deeper level of internalization, both managers and employees will have difficulty in commitment and ownership of the practice (Kostova, 1999; Rowley & Benson, 2002).

Employee Development Investment

A well-trained and educated labor force is considered a major contributor to the economic performance records of Asia (Cooke, 2005). The need for skilled professions and high-quality executive training have created a boom for managerial training courses, MBA programs, and higher education opportunities in Asia. While an attractive choice for larger corporations, not every company has the resources to establish in-house training schools. Therefore, some large companies may send employees abroad to foreign universities for training. Small-and-medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) need to rely more on governments. China and Vietnam have only recently joined the WTO (2001 and 2007, respectively), strengthening international educational exchange and helping distribution and application of new knowledge.

Nevertheless, not all Asian countries employ a Western approach to development, but blend practices with Asian characteristics and institutional needs. The focus of management training in Korea, especially in large companies, is somewhat different than in the West. In Korea, emphasis was placed on team spirit and commitment to the company and coworkers (Drost, Frayne, Lowe, & Geringer, 2002). Companies took a more holistic approach to incorporate company value and business practices in people development.

Again, however, the sectoral and hierarchical coverage and spread of such practices can be questioned. It is a common finding that the most senior HR in organizations receive the most development expenditure.

In sum, our overview of these three HRM practices shows that it seems that HRM change involves gradual experimentation, and best practices cannot simply be adopted. As with most experimentation, the final outcomes may be difficult to predict and, hence, pose challenges in management research in such area.

Future Directions

This research paper provides an understanding of the issues of the transfer of best HRM practices to Asia. Three HRM practices (employment, rewards, and development) were examined in various countries. In general, internal and external

forces have led to pressures to transfer HRM best practices to Asian economies, but these also feel the force of resistance from contingent variables (location, sector, etc.) and, to some degree, have developed differently from the West. Converging to one best practice HRM is still debatable.

Cannot Conclude Full Transfer

Our first proposition is that market forces can generate a transfer of HRM best practices. We do find some support in that economic forces and technology are leading to a certain degree of HRM transfers to Asia-Pacific economies and, hence, some convergence. Changes are at a transitional stage, however, and the final outcome is difficult to predict. Warner’s (2000) framework advocates four categories: (a) hard convergence, (b) soft convergence, (c) soft divergence, and (d) hard divergence. He speculates that the most likely outcomes for Asian economies would be variations of soft convergence and soft divergence, which might come through a number of similar global forces and lead to outcomes heading in different directions. A new format of organization, “perhaps analogous to the ‘limited company’ system in Western economies” (Warner, 2003, p. 28), may result.

It is too early to conclude that all Asian HRM is likely to converge to one model. HRM remains distinctive at the national level. It would be better to characterize the transfer of HRM practices as incremental and toward a distinct model with Asian characteristics (as suggested in proposition 2).

Past Success in One Situation Not Sufficient for Elsewhere

A great number of management practices, not just HRM, contain underlying assumptions and conditions for their successful application. As such, past success or best practice in one situation does not automatically guarantee an effective transfer and adoption in another, such as location. Conflicts with cultural values, institutional environments, and other conditions are likely. The interaction between various business contexts and cultures means that each country might develop its own unique HRM system.

Our analysis shows that success stories of HRM best practices in Asian countries have been mixed. The literature identifies a number of factors that support or hinder the transferability of HRM policies and practices. First, the meaning and operation of particular HRM practices can vary substantially between countries. Second, Asian development does not follow a homogenous model. Some economies in certain areas, such as China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and so on, retain heavy state involvement in business settings. Third, the country of origin of the parent company, host-country institutions and legislation, expatriate managers, the company business strategy, and so on, all have effects on practice transfer. Future research should be customized to take into account such differences and nuances.

Practice Transfer and Making It Effective

Practices associated with the HRM model have been transferred, to various extents, to companies in Asia. Yet, many practices have not yet been fully internalized in policy choices or system architecture. As Rowley and Benson (2002) pointed out, adoption of the HRM model is strongest at the level of practice and weaker at the policy or architectural levels in Asia. The lack of significant change at the policy and architectural levels suggest that some unique attributes remain crucial constraints on adoption. In addition, practice transfer is one thing, but making it effective is another.

Acceptance of the HRM concept by transfers of practices to Asian companies has been slow and cautious. It seems that experimentation with Western HRM practices will continue and, in all likelihood, will be modified to suit the unique needs of each system (Benson, Debroux & Rowley, 2004). Future studies need to be directed to a deeper level of the HRM system for a better understanding of the degree of transfer. Studies of employee commitment and ownership of practices can better reflect whether adoption has or has not been consolidated.

Furthermore, institutional and cultural factors can restrict full transference, and so convergence, in HRM systems. The sheer variation of geography, population, economic growth, labor markets, and values means that converging to one best practice model of HRM is difficult, if not unlikely. While there are some signs of convergence among Asian economies in the direction of trends, very substantial differences in terms of final convergence remain. Things appear to change slowly in HRM. Researching over a longer time frame is desirable to show consolidation of HRM model.

Challenge to Conduct Research in Transitional Stages

The transfer of some best practices has happened in Asian countries, but not all practices have worked or simply been adopted, for example, the introduction of performance-based pay and subsequent reversion to seniority-based systems in Japan, the modification of training programs in Korea and China, and so forth. Experimentation with best practices will continue, but will be modified to suit the unique Asian characteristics such as local social, cultural, political, and legislative systems (Rowley & Bae, 2004; Rowley & Benson, 2002).

A high degree of uncertainty will continue to exist in the transitional experimental stage. Research on HRM in Asia can also pose other challenges. Most of the existing theories and research paradigms have origins in the West with limited Asian elements. This trend often means expecting Western management theories to fit in other contexts rather than searching for new concepts to explain similarities and differences between Western and Asian ones and so, may not be ideal (Poon & Rowley, 2007). The main concern is not that

Western theories and frameworks do not recognize differences between Western and Asian institutions and cultures, which they can do. The issue is that the studies may not capture and represent the underlying cultural and philosophical assumptions and, as such, end up underrepresenting or misrepresenting Asian conceptions of HRM (Poon & Rowley, 2007). More investment and effort to develop models and frameworks to suit Asian contexts are desirable.

Summary

This research paper discussed the issue of the possible transfer of best practices to the Asia-Pacific region. Globalization, institutional forces, and benchmarking have turned out to be some drivers of the reconfiguration of Asian HRM toward a more Western HRM type. The influences of foreign impacts through FDI, MNCs, Internet usage in business, and so forth, are also revolutionizing business and management. Some HRM best practices, for instance, employment flexibility, performance-based rewards, and employee development investment, can be observed across the region.

Despite continued assertions that the transfer of some HRM best practices has occurred, however, hard, descriptive (as opposed to prescriptive or normative) evidence does not support a convergence toward a Western model for Asian economies. Asian economies experiment with technology, techniques, and managerial practices from the West and modify them to suit their needs. Acceptance of best practices by Asian companies has been slow, and many best practices have not yet been fully internalized in policy choices or system architecture. The sheer variation of geography, economic growth, and labor markets, as well as cultural values, implies that converging to one best practice Asian HRM model can be difficult to sustain.

Bibliography:

- Adler, N. J., & Ghadar, F. (1990). Strategic HRM: A global perspective. In R. Pieper (Ed.), HRM in international comparison (pp. 235-260). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Bae, J., & Rowley, C. (2001). The impact of globalization on HRM: The case of South Korea. Journal of World Business, 36(4), 402M28.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

- Barney, J. (1995). Looking inside for competitive advantage. Academy of Management Executive, 9(4), 49-61.

- Becker, B. E., & Gerhart, B. (1996). The impact of HRM on organizational performance: Progress and prospects. Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 779-802.

- Benson, J., & Debroux, P. (1997). HRM in Japanese enterprises: Trends and challenges. Asia Pacific Business Review, 3(4), 62-81.

- Benson, J., & Debroux, P., & Rowley, C. (2004). Conclusion: Changes in Asian HRM—implications for theory and practice. In C. Rowley & J. Benson (Eds.), The management of HR in the AP region: Convergence reconsidered (pp. 186-193). London: Frank Cass.

- Björkman, I., & Xiucheng, F. (2002). HRM and the performance of Western firms in China. International Journal of HRM, 13(6), 853-864.

- Boxall, P., & Purcell, J. (2003). Strategy & HRM. London: Pal-grave.

- Briscoe, D. R. (1995). International HRM. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Caligiuri, P. M., & Stroh, L. K. (1995). Multinational corporation management strategies and international HR practices: Bring IHRM to the bottom line. International Journal of HRM, 6(4), 494-507.

- Chow, I. H. (2004). The impact of institutional context on HRM in three Chinese societies. Employee Relations, 26(6), 626642.

- Cooke, F. L. (2005). Vocational and enterprise training in China: Policy, practice and prospect. Journal of the AP Economy, 10(1), 26-55.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational field. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147-160.

- Dowling, P. J. (1989). Hot issues overseas. Personnel Administrator, 34(1), 66-72.

- Dowling, P. J., Schuler, R. S., & Welch, D. E. (1994). International dimensions of HRM. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

- Drost, E. A., Frayne, A., Lowe, B., & Geringer, J. M. (2002). Benchmarking training and development practices: A multi-country comparative analysis. Human Resource Management, 41(1), 67-88.

- Easterby-Smith, M., Malina, D., & Lu, Y. (1995). How culture sensitive is HRM? A comparative analysis of practice in Chinese and UK companies. International Journal of HRM, 6(1), 31-59.

- Edwards, T., & Ferner, A. (2002). The renewed “American challenge”: A review of employment practice in U.S. multinationals. Industrial Relations Journal, 33(2), 94-111.

- Finegold, D., & Soskice, D. (1988). The failure of training in Britain: Analysis and prescription. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 4(1), 21-53.

- Gonzalez, S. M., & Tacorate, D. V. (2004). A new approach to the best practices debate: Are best practices applied to all employees in the same way? International Journal of HRM, 15(1), 56-75.

- Hamilton, G. (1995). Overseas Chinese capitalism. In W. Tu (Ed.), The Confucian dimensions of industrial East Asia (pp. 112-125). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations around the globe. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of HRM practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38(3), 635-670.

- International Monetary Fund. (n.d.). World economic outlook databases. Retrieved August 17, 2007, from http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28

- Jackson, S. E., Schuler, R. S. & Rivero, J. (1989). Organizational characteristics as predictors of personnel practices. Personnel Psychology, 42(4), 727-786.

- Japan Institute of Labor Policy and Training. (2004). Report published by Japan Institute of Labour Policy and Training.

- Retrieved August 17, 2007, from http://www.stat.go.jp/eng lish/index.htm

- Kerr, C., Dunlop, J. T., Harbison, F. H., & Meyers, C. A. (1962). Industrialism and industrial man. London: Heinemann.

- Kostova, T. (1999). Transnational transfer of strategic organizational practices: A contextual perspective. Academy of Management Review, 24(2), 403-428.

- Lado, A. A., & Wilson, M. C. (1994). HR systems and sustained competitive advantage: A competency-based perspective. Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 699-727.

- Legge, K. (1989). HRM: A critical analysis. In J. Storey (Ed.), New perspectives on HRM. London: Routledge.

- Marchington, M., & Wilkinson, A. (2005). Human resource management at work. London: CIPD.

- Martel, L. (2003). Finding and keeping high performers: Best practices from 25 best companies. Employment Relations Today, 30(1), 27-43.

- McKinley, W., Senchez, L., & Schick, A. G. (1995). Organizational downsizing: Constraining, cloning, learning. Academy of Management Executive, 9(3), 32-44.

- Michie, J., & Sheenhan, M. (2005). Business strategy, human resources, labour market flexibility and competitive advantage. International Journal of HRM, 16(3), 445-164.

- Oliver, N., & Wilkinson, B. (1992). The Japanization of British industry: New developments in the 1990s. London: Heinemann.

- Pfeffer, J. (1994). Competitive advantage through people. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Pfeffer, J. (1998). The human equation: Building profits by putting people first. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Poon, H. F., & Rowley, C. (2007). Contemporary research on management and HR in China: A comparative content analysis of two leading journals. Asia Pacific Business Review, 13(1), 133-153.

- Pudelko, M. (2005). Cross-national learning from best practice and the convergence-divergence debate in HRM. International Journal of HRM, 16(11), 2045-074.

- Rasiah, R. (2004). Exports and technological capabilities: A study of foreign and local firms in the electronic industry in Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand. European Journal of Development Research, 16(3), 587-623.

- Redman, T., & Wilkinson, A. (2006). Contemporary human resource management. London: FT/Prentice Hall.

- Rowley, C. (Ed.). (1998). HRM in the Asia Pacific region: Convergence questioned. London: Frank Cass.

- Rowley, C., & Bae, J. (2004). HRM in South Korea after the

- Asian financial crisis. International Studies of Management & Organization, 34(1), 52-82.

- Rowley, C., & Benson, J. (2002). Convergence and divergence in Asian HRM. California Management Review, 44(2), 90-109.

- Rowley, C., & Benson, J. (Eds.). (2004). The management of human resource in the Asia Pacific region: Convergence reconsidered. London: Frank Cass.

- Rowley, C., Benson, J., & Warner, M. (2004). Towards an Asian model of HRM? A comparative analysis of China, Japan and South Korea. International Journal of HRM, 15(4), 917-933.

- Rowley, C., & Warner, M. (2007). Globalizing international HRM?. International Journal of HRM, 18(5), 703-716.

- Sinha, D., & Kao, H. S. R. (1988). Introduction: Values-development congruence. In D. Sinha & H. S. R. Kao (Eds.), Social values and development: Asian perspectives (pp. 10-27). New Delhi: Sage.

- Snell, S. A., Lepak, D. P., Dean, J. W., & Youndt, M. A. (2000). Selection and training for integrated manufacturing: The moderating effects of job characteristics. Journal of Management Studies, 37(3), 445-467.

- Sturdy, A. (2004). The adoption of management ideas and practices: Theoretical perspectives and possibilities. Management Learning, 35(2), 155-179.

- Takeuchi, N., Wakabayashi, M., & Chen, Z. (2003). The strategic HRM configuration for competitive advantage: Evidence from Japanese firms in China and Taiwan. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 20(4), 447-480.

- Taylor, F. (1911). Scientific Management. New York: Harper and Row.

- Thang, L. C., Rowley, C., Troung, Q., & Warner, M. (2007). To what extent can management practices be transferred between countries: A comparative analysis of China, Japan and South Korea. Journal of World HRM, 42(1), 113-27.

- Thompson, M., & Heron, P. (2005). Management capability and high performance work organization. International Journal of HRM, 16(6), 1029-1048.

- Tolbert, P., & Zucker, L. (1996). The institutionalization of institutional theory. In S. Clegg, C. Hardy, & W. Nord (Eds.), Handbook of organization studies (pp. 175-190). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Warner, M. (1995). The management of HR in Chinese industry. London: Macmillan.

- Warner, M. (2000). Introduction: The Asia Pacific HRM model revisited. International Journal of HRM, 11(2), 171-182.

- Warner, M. (2003). China’s HRM revisited: A step-wise path to convergence? Asia Pacific Business Review, 19(4), 15-31.

- Yuen, E. C., & Kee, H. T. (1993). Headquarters, host-culture and organizational influences on HRM policies and practices. Management International Review, 33(4), 361-383.