Sample Genetic Counseling Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Genetic counseling is one of the most important direct applications of human genetic knowledge. Genetic counseling refers to the totality of activities that (a) establish the diagnosis of genetic disease, (b) assess the occurrence risk, (c) communicate to the patient and family the chance of recurrence, (d) provide full and unbiased information within a caring relationship regarding the many problems raised by the disease and its natural history, including the potential ethical conflicts as well as the medical, economic, psychological, and social burdens, and (e) provide information regarding the reproductive options to be taken, including prenatal diagnosis, and refer the patients to the appropriate specialists. Genetic counseling should offer guidance but will allow those being counseled to arrive at their own choices, both before and after genetic procedures (Vogel and Motulsky 1997; World Health Organisation [WHO] 1998).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Paradigm Development And Concepts Of Genetic Counseling

Pre-scientific knowledge of heritability in humans dates back to the early Greek physicians and philosophers and it can be assumed that there have been practical measures, including advice to individuals and couples as to how to use such knowledge (Vogel and Motulsky 1997). The idea of an improvement of mankind by rationalized mate selection was a major aspect of ancient and Renaissance state and social utopias (Plato, Politeia (about 374 BC); Thomas More, Utopia (1516); Fra Tomaso Campanella, The City of the Sun (1623)). In the medical literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, reports on the familial recurrence of particular disorders begin to accumulate. An early and noteworthy example is the book of the English physician Joseph Adams (1756–1818) A Treatise on the Supposed Hereditary Properties of Diseases (1814), where an attempt is made to lay out the fundamentals of genetic counseling in affected families.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, two paradigms established human genetics as a science. Gregor Mendel (1822–1884) founded the concept of the gene as the basic factor of inheritance (1866), while Francis Galton (1822–1911) introduced statistical methods to investigate and interpret the familial clustering of traits and thus founded the biometrical paradigm. Until the present, biometrics and Mendelian genetics have remained the basis of risk determination as the naturalistic component of genetic counseling. Galton coined the term ‘eugenics’ and favored measures to enhance propagation of individuals with supposedly high genetic qualities (positive eugenics). In Germany, around the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century, Wilhelm Schallmeyer (1857–1919), Alfred Hegar (1830–1914), and Alfred Ploetz (1860–1940) developed the idea of negative eugenics, a concept of decreasing the number of offspring of individuals with supposedly below average hereditary qualities, or of preventing congenitally diseased individuals altogether, with the aim of improving the gene pool of future generations and especially that of the presumed superior Nordic race (see Ploetz 1895).

In many countries during the first half of the twentieth century, positive and negative eugenics formed the ideological basis of state-enforced measures to exert reproductive control over individuals. Between 1911 and 1930, 24 US states proclaimed sterilization laws and eugenic thought also played a role in the enactment of restrictive immigration laws. In Europe, Denmark was the first country to proclaim a Law on Genetic Hygiene (1929), in which voluntary sterilization for genetic reasons was regulated. In Germany, the Law for the Prevention of Congenitally Diseased Progeny (1933), followed by a series of other laws and decrees, mandated and/organized the sterilization of individuals with certain diseases, which were thought to be genetically determined. In Germany, eugenics, racial hygiene, and National Socialist ideology formed a gloomy alliance. The involvement of German geneticists in coercive measures and eventually the Holocaust to sections of the population that were declared to be inferior has been well documented by MullerHill (1997). It is beyond doubt that this historical burden strongly influences the current debate on ethics and genetics in Germany and elsewhere.

From about 1930 onwards, the eugenic movement outside Germany began to lose power, but it was not until the 1950s that the population-directed eugenic orientation was slowly replaced by a medically oriented practice with genetic disease prevention as a major focus. Nevertheless, eugenic thinking, whether acknowledged or not, has continued to play a role until the present time, especially outside the Western world (Wertz 1997). When, in 1947, Sheldon Reed coined the term ‘genetic counseling,’ it became clear that eugenics and what was then understood to be genetic counseling, were no longer identical. According to Reed, ‘genetic counseling is a type of social work entirely for the benefit of the whole family without direct concern for its effect upon the state or politics’ (1974). This definition marks a change of paradigm in applied human genetics, away from the concern about the genetic make-up of the population and towards the attitude that decision-making with regard to genetic risks should be left to the individual, even if this may create or increase social costs or worsen the gene pool. Thus, one of the fundamental ethical principles in medicine, the respect for the autonomy and self-determination of persons, is also the cornerstone of genetic counseling.

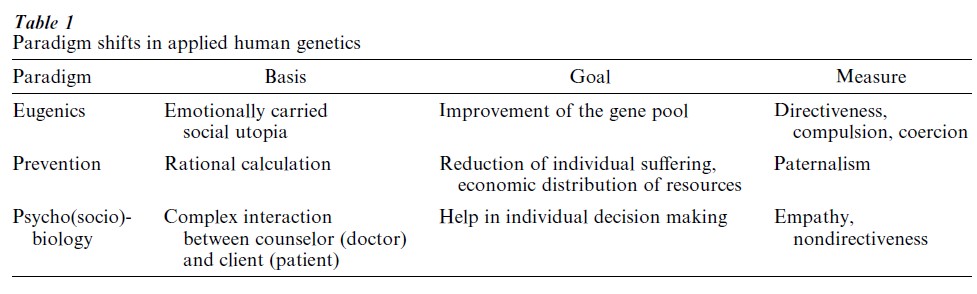

Genetic counseling has thus gone through three overlapping historical phases (Table 1). First, the eugenics phase, mainly rooted in England, the United States of America, Scandinavia, and Germany, was based on the social and biological utopia of general mental and physical health and the optimization of humankind. In order to attain these goals, depending on political circumstances, directive measures including direct and indirect coercion were applied. Eugenics was scientifically ill-founded, and the definition of inferior or superior genetic qualities a matter of ideology. Second, the preventive-medical phase laid its emphasis on the reduction of individual suffering through the prevention of genetic diseases and disabilities, in order to economize rare medical resources. It was founded on the rational calculation that any means towards that end would find acceptance as being in the immediate interest of the individual. Strategies were those of benevolence, authority, and paternalism. Third, in the psycho-(sociobio-)logical phase, the focus of genetic counseling is to help the individual or the family to manage a problematic situation caused by genetic disease. The basis of this help is a complex interaction between the counselor (a specialized physician or a non-medically trained expert) and the client (patient) in a nondirective process of communication. Help is provided with the understanding that genetic diseases are often associated with special psycho-social problems and ethical conflicts which deserve to be managed individually. Thus, any direct or indirect coercive influence is to be avoided. Nondirectiveness has become a basic concept of genetic counseling, to which a majority of counselors worldwide feel obliged (Wertz 1997).

The history of genetic counseling shows that its purpose has always been value-determined and has never been seen outside the context of social politics in which it was embedded. In countries that acknowledge human rights as defined in the democratic state theories of the eighteenth century, the only defensible position is that of the autonomy of the individual to make decisions regarding genetic counseling and genetic diagnosis, and to draw consequences for life and family planning. The healthcare system, on the other hand, carries the ethical obligation to provide full information and the tools that may enable the individual, depending on the state of knowledge, the emotional situation, and moral positioning, to make use of that information.

1.1 Excursus: Ethics And Genetic Counseling: The Respect For Personal Autonomy

Today the term ‘eugenics’ is sometimes used to describe the cumulative result of individual choices after genetic counseling, especially in view of reproductive choices. The decreasing prevalence of births of children with Down Syndrome in Western Europe, especially in the UK, may be regarded as a result of individual choices to undergo prenatal diagnosis and subsequently to terminate a pregnancy after a positive test result. Whether this type of individual eugenics is socially desirable and a benign development has been discussed with some controversy by Wertz (1998). Critics argue that free, autonomous choices (after genetic counseling) not only depend on surrounding social, cultural, and other factors, but also on the full and honest presentation of information in genetic counseling, i.e., on access to valid information. In the absence of correct and unbiased information, free choices are not possible and are compromised, and information and genetic counseling becomes a means of furthering attitudes and goals of health professionals. A worldwide survey of 2,091 genetics professionals in 36 nations conducted by Wertz (Nippert and Wolff in Germany) suggests that eugenic thought underlies the perception of the goals of genetics and genetic counseling in many countries. In developing nations of Asia and Eastern Europe especially, directive counseling is practiced to influence individual decisions. Intentionally pessimistically biased information is routinely provided after positive results from prenatal diagnosis in order to avoid the birth of affected children (Wertz 1998, Cohen et al. 1997). The data from this survey suggests that the concept of nondirective counseling found in English-speaking nations and Western Europe is an aberration from the rest of the world.

2. Indications For Genetic Counseling

In medicine in general, a measure is ‘indicated,’ when, after weighing up the risks and benefits, it appears medically required. This definition is hardly applicable to genetic counseling, because the recognition of risks and benefits of knowledge, as well as any actions that may result from such knowledge, will emerge only in the counseling process itself, and their appraisal is often more strongly determined by individual life circumstances than by medical judgment. On the other hand, the professionalization of genetic counseling, as a specialization within medicine, and jurisdiction in regard to correctness and completeness of any medical advice, have brought about a core service that every counselee may duly expect to receive: A scientifically founded statement regarding the etiology and the (recurrence) risk of a genetic condition, comprehensive information and counseling regarding diagnostic options, and referral to preventive, therapeutic, and/or socially alleviating measures.

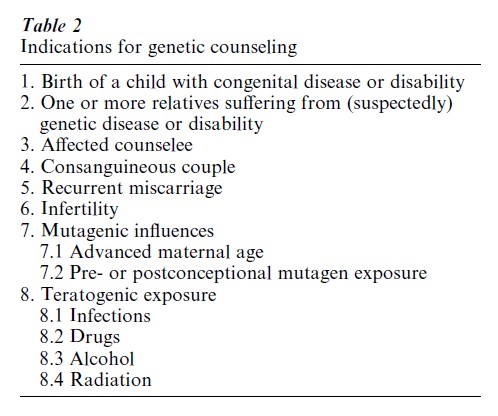

Generally speaking, an indication for genetic counseling is given whenever an individual regards it as a means to help solving a personal problem related to an existing or suspected genetic risk. Table 2 summarizes the most frequently encountered situations. With increasing awareness of old and novel pre- and postnatal methods of genetic diagnosis, genetic counseling is increasingly sought by individuals with genetic risks not immediately apparent to themselves. Concerns, including moral doubts, may have been raised, for example, by offers of prenatal screening (maternal serum marker and ultrasound screening), or carrier detection, within or outside the framework of a defined screening programme, because such offers may bring up the question of termination of the pregnancy.

3. The Counseling Process

According to a statement issued by an Ad hoc Committee on Genetic Counseling of the American Society of Human Genetics, genetic counseling is a communication process which:

deals with the human problems associated with the occurrence or risk of recurrence of a genetic disorder in a family. This process involves an attempt by one or more appropriately trained persons to help the individual or the family to 1. comprehend the medical facts, including the diagnosis, the probable course of the disorder, and the available management; 2. appreciate the way heredity contributes to the disorder and the risk of recurrence in specified relatives; 3. understand the options for dealing with the risk of recurrence; 4. choose the course of action which seems appropriate to them in view of their risk and their family goals and act in accordance with that decision; 5. make the best possible adjustment to the disorder in an affected family member and/or to the risk of recurrence of that disorder (Fraser 1974; Ad hoc Committee on Genetic Counseling 1975).

The counseling process is usually initiated by clarifying the counselee’s motivation for consultation. What is the background to the problem, and what are the expectations? The counselor should explain, in general terms, what genetic counseling can achieve, and where its limits lie. This is important, because expectations are frequently unrealistic. It needs to be explained, for example, that it is technically not possible to exclude any kind of genetic risk, or to guarantee a healthy child. The next step is to record the personal and family medical history in the form of a genealogical tree, encompassing at least all first and second degree relatives. This is followed by providing information regarding the most important medical facts concerning the disease in question (natural history of the disease, the likely degree of suffering it may confer, its treatability) as well as the likelihood of its occurrence or recurrence. It is important to give unbiased, objective information. During the later phases of the counseling process, the counselor will often return to this information in order to relate it to the personal views of the counselee. The ‘prior’ risks for a genetic condition as deduced from its pattern of inheritance (monogenic dominant or recessive, autosomal or sex-linked, co-determined by several genes and/or the environment) may be modifiable by genetic diagnostic tests so that a ‘posterior,’ usually more precise, risk figure emerges. Ever more often, with the Human Genome Project nearing its completion and concomitant technical developments becoming routine practice, firm confirmation or exclusion of carrier status for any particular genetic disposition will be the rule, rather than the exception. Nevertheless, the phenotypic outcome will often be variable, due to environmental factors and complex interactions between genes. In the counseling process, the resulting uncertainty needs to be explained and worked upon with great care. Without thoroughly understanding the chances and limits of genetic testing, an informed consent to any such procedure cannot be attained. Informed consent is generally held to be the prerequisite for any genetic testing. The decision whether to make use or not of diagnostic offers can only be made sensibly in a highly personalized context, so that genetic counseling is required to be nondirective (Wolff and Jung 1995).

During the counseling process it may be necessary to make a physical examination of the counselee and/or of family members in order to search, for example, for early signs of manifestation of a lateonset disorder or for micro- symptoms of a disease. The impact of such examination needs to be explained beforehand, because counselees and their family members may wish to help clarify genetic risks for others, but not necessarily for themselves. It is sometimes difficult to decide to what extent information from the family history which may confer a genetic risk to the counselee needs to be discussed, if this information has not been central to the counselee’s motivation for consultation. This is particularly delicate when no therapeutic or preventive options exist. If they do, however, the counselee has a right to comprehensive information and counseling.

4. The Determination Of Genetic Risks

The determination of genetic risks in any individual case is the essential naturalistic component of genetic counseling. It requires expertise in general and human genetics, including formal (mathematical) genetics, population genetics, and clinical genetics, as well as an awareness (attainable in this fast-moving field only through continuous further self-education) of novel developments, especially in the differential genetic diagnosis. In the following discussion, we provide a summary of the most important groups of conditions where a risk assessment is often sought and a brief outline of risk provision. Often, the prior genetic risks need to be modified by using information from the pedigree or genetic tests (conditional probabilities). By employing Bayesian methodology this information can be used to arrive at posterior (final) risks (Harper 1998).

If a disease is (mainly) due to the effect of a single gene, the phenotype may be inherited in a recessive or a dominant fashion. The disease may manifest itself in a sex-dependent way, if the causative gene is not located on the autosomes (the chromosomes shared by both sexes in equal number) but rather on the sex chromosomes (X and Y). In an autosomal-recessive condition, the recurrence risk in a sibship is 1/4, but usually low (less than 1 percent) for second-degree relatives. If a parent has an autosomal-dominant condition, there is a 50 percent chance that each child will also carry the disease-causing mutation. If neither parent has a condition that is known to be autosomal dominant, the recurrence risk in a sibship is usually negligible, because the presumption is that a spontaneous mutation has occurred in the germ-line leading to the affected individual. In X-linked recessive disease, if the mother is a carrier, half of all her sons will develop the full clinical picture, and half of her daughters will be carriers. Mothers and daughters are usually unaffected or exhibit symptoms to a lesser degree (due to non-randomness of X-inactivation during early development). In Y-linked disease (such as sub-fertility), the trait is passed on from fathers to sons. In both recessive and, most notably, dominant conditions, the inheritance patterns may be obscured by variable penetrance (proportion of carriers manifesting the phenotype at all) and expressivity (degree of disease severity). Greatly reduced penetrance and expressivity, i.e., where only a small fraction of carriers suffer from the condition, leads to the concept of genetic predisposition (susceptibility) for disease, which may be modulated by other genes or environmental factors. Polygenic and multifactorial inheritance are the etiology of most of the common diseases (such as coronary heart disease, obesity, diabetes mellitus) and the majority of cases of birth defects. In these categories, empirical risk figures apply. Numerical chromosomal aberrations are usually sporadic, with a low empirical recurrence risk in a sibship, but may also run in families, e.g., structural aberrations, such as translocations, which may be inherited as balanced or unbalanced in offspring in a more or less apparent Mendelian fashion.

5. Genetic Counseling In The Social Context

How have genetic counseling and its supposed high standards fared in common practice? Throughout the world and even in Europe, there is a huge variance in the professional identity and training of providers of genetic counseling services. In Germany, most counseling services are provided by physicians who are specialists in medical genetics (Nippert et al 1997) and in the UK, genetic counseling is provided primarily by nurses (Raeburn et al 1997), whereas in the US and Canada a substantial amount of genetic counseling is provided by counselors trained to the master’s degree level. This implies that practice differs between countries. Surveys which compare the attitudes of genetic service and counseling providers have revealed a remarkable difference in attitudes and values. An international survey carried out in 37 nations in 1994–1995 found that, in most of the surveyed countries, genetic counseling, especially in the context of prenatal diagnosis (PD), is directive in that the counselor provides the client with intentionally slanted information in order to influence the client’s decision (Wertz 1998). The survey shows that, depending on the diagnosed conditions of a fetus, on the culture’s view of the condition, and on the counselor’s personal view about the morality of abortion, he or she deliberately provides more optimistically or pessimistically biased information.

Although published policies and guidelines exist (Fraser 1974, German Society of Human Genetics 1996, Andrews et al 1994, WHO 1998, Fryer and Lister Cheese 1998, Holtzman and Watson 1997), the type of information and the way information is communicated vary within countries, and standard practices can hardly be found. Obviously genetic counseling practices are shaped by the characteristics of the various healthcare systems, as well as by the personal characteristics of the counselor, such as sex, professional expertise, and type of employment. The process and outcomes of genetic counseling have been documented by a few empirical studies (Sorenson 1992). The outcomes have been defined primarily on the basis of patient knowledge and patient satisfaction, but so far have hardly paid any attention to the social aspects of the information (Clarke et al 1996). Concern has been voiced that in the future more counseling will be provided by professionals not trained in genetics. Although there is insufficient empirical evidence that genetic counselors successfully achieve autonomous, informed decision-making, research from Europe and the US suggests that non-geneticists do not set a high value on providing information that allows informed decision-making before undergoing tests such as prenatal diagnosis (Dodds 1997).

With the development of more new molecular tests, implementation of these tests in various fields of medicine will drive the diversification of genetic counseling practice. Neither general healthcare providers nor non-genetics specialists have sufficient professional education and expertise in genetics, molecular testing, and genetic counseling to perform this task (Holtzman and Watson 1997). How to target the education for providers via medical curricula and continuing education remains an unsolved challenge. So far, no country has developed any strategy or has made any far-reaching efforts. Genetic specialists are arguably the most valid source for providing the needed expertise and information for their medical colleagues to facilitate their understanding of basic genetic principles and the application of molecular testing, including pre and post-test counseling, in clinical practice. However, the more genetics becomes part of general medicine and the more genetic testing is introduced into the various specialty areas, the more the task to provide information and to interpret test results will fall on primary care physicians and nongenetics specialists. Probably the future of genetic services will be provided in the way envisaged by Wertz:

It is perhaps more likely that most genetic services will be provided in the same manner as other types of medicine. In managed care systems this may mean hurried, assembly-like encounters that focus on tests and treatments rather than on providing information and counseling. Most primary care providers may be ill-equipped to provide information and counseling needed in any case … Many will wonder why genetics was ever expected to produce superior providerpatient relationships, to uphold superior ethical standards, or to allow greater patient autonomy than other fields of medicine (1997, p. 343).

Most likely the future of genetic testing and counseling will be shaped by economic interests, because of the need for financial returns on heavy investments made in the field of molecular testing, by reimbursement practices, and by the extent to which national healthcare policies will encourage genetic testing. It remains unclear whether the main ethical concepts attached to genetic counseling, such as nondirectiveness, individual autonomy, and greater equality in the doctor-patient relationship, will survive or will wither away during the integration of genetic tests into routine medical practice. Hopefully genetic counseling will retain some of its best elements, namely respect for patients’ rights to valid, non-slanted information and for patient autonomy in reproductive decision-making.

Bibliography:

- Ad hoc Committee on Genetic Counseling of the American Society of Human Genetics 1975 Genetic counseling. American Journal of Human Genetics 27: 240–2

- Andrews L B, Fullarton J E, Holtzman N A, Motulsky A G (eds.) 1994 Assessing Genetic Risks. Implications for Health and Social Policy. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

- Clarke A, Parsons E, Williams A 1996 Outcomes and process in genetic counseling. Clinical Genetics 50: 462–9

- Cohen P E, Wertz D C, Nippert I, Wolff G 1997 Genetic counseling practices in Germany: A comparison between East German and West German geneticists. Journal of Genetic Counseling 6: 61–80

- Dodds R 1997 The Stress of Tests in Pregnancy: Summary of a National Childbirth Trust Screening Survey. National Childbirth Trust, London

- Fraser F C 1974 Genetic counseling. American Journal of Human Genetics 26: 636–59

- Fryer A E, Lister Cheese I A F 1998 Clinical Genetic Services: Activity, Outcome, Effectiveness and Quality. Report from the Clinical Genetics Committee of the Royal College of Physicians of London, The Royal College of Physicians of London, London

- German Society of Human Genetics 1996 Position paper, http: //www.gfhev.de

- Harper P 1998 Practical Genetic Counseling. 5th ed. Butterworth-Heinmann, Oxford, UK

- Holtzman N A, Watson M S 1997 Promoting Safe and Effective Genetic Testing in the United States. Final Report of the Task Force on Genetic Testing. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. http://www.med.jhu.edu tfgtelsi/

- Human Genome Project, ht tp://www. Orn/l.gov/Tech/ Resources Human Genome home.html

- Muller-Hill B 1997 Murderous Science: Elimination by Scientific Selection of Jews, Gypsies and Others in Germany 1933–1945. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Nippert I, Horst J, Schmidtke J 1997 Genetic services in Germany. European Journal of Human Genetics 5 (suppl 2): 81–8

- Ploetz A 1895 Racial hygiene. In: Weingart P, Knoll J, Bayertz K (eds.) Rasse, Blut und Gene. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt Main, Germany

- Raeburn S, Kent A, Gillot J 1997 Genetic services in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Human Genetics 5 (suppl 2): 188–95

- Reed S C 1974 A short history of genetic counseling. Social Biology 21: 332–9

- Sorenson J R 1992 What we still don’t know about genetic screening and counseling. In: Annas G J, Elias S (eds.) Gene Mapping: Using Law and Ethics as Guides, Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 203–14

- Vogel F, Motulsky A G 1997 Human Genetics. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, New York

- Wertz D C 1997 Society and the not-so-new genetics: What are we afraid of? Some future predictions from a social scientist. Journal of Contemporary Health Law Policy 13: 299–346

- Wertz D C 1998 Eugenics is alive and well: A survey of genetic professionals around the world. Science in Context 11: 493–510

- Wolff G, Jung C 1995 Nondirectiveness and genetic counseling. Journal of Genetic Counseling 4: 3–25

- World Health Organisation 1998 Proposed International Guidelines on Ethical Issues in Medical Genetics and Genetic Services. World Health Organisation Human Genetics Programme, Geneva. http://www.who.int/ncd/hgn/hgnethic.htm