Sample International Migration By Ethnic Asians Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Introduction

South (including the countries of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka) and Southeast Asia (including the countries of Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar) are home to 31 percent of the world’s population at the turn of the twentieth century (1,879.4 million persons) and the region has experienced massive population change since the 1980s (Leete and Alam (1993). The rapid increase in population movement between countries that has accompanied the process of globalization in this period in all of the countries of this region has been affected significantly. There has been a major increase in the levels, complexity, and impact of international migration in the region. Whereas at the end of the 1970s such movement was limited to a selected small proportion of residents in the region, it is now within the calculus of choice of a major part of the population as they weigh up their life chances. With the increase in movement has come an increased awareness of it and intervention to influence it by governments in the region. This research paper seeks to summarize the evolving patterns of movement and address some of the major issues relating to it.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

2. Patterns

The data available to examine international migration in South and Southeast Asia are limited in the extreme. The increase in significance and intensity of movement has outpaced the development of data systems to measure it. Moreover, undocumented migration in the region is arguably as great in scale as legal migration and, by definition, the information relating to that migration is limited. While there is a great deal of complexity in the spatial patterning of the movement, the degree of permanency, the characteristics of movers, and its legality, it is possible to identify three main subsystems of movement in the region. These include a so-called south–north, more-or-less permanent flow to developed countries, a predominantly temporary labor flow to the Middle East, and a third set of interactions within the region. Each subsystem involves different balances of forced and non-forced movement, males and females, permanent and nonpermanent, documented and undocumented, labor related and other movement, etc.

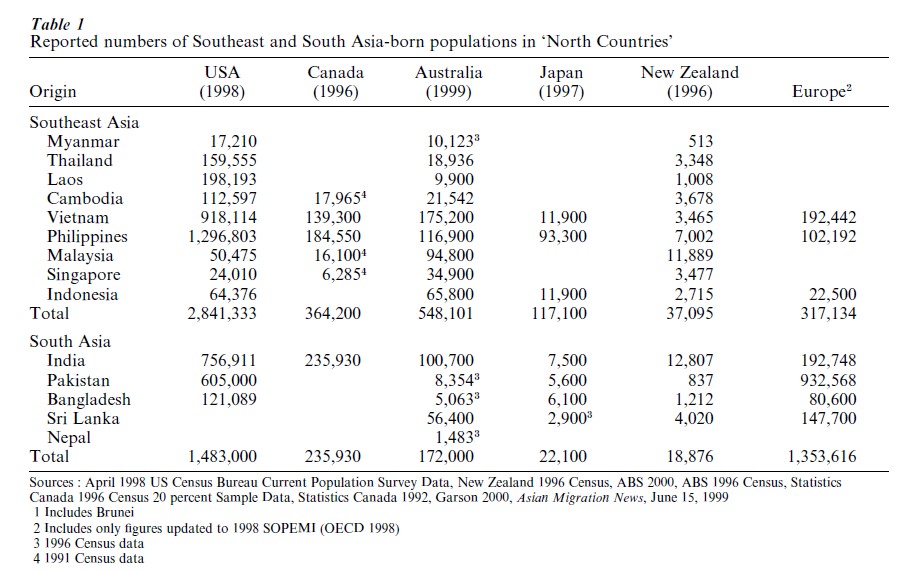

South–north movement is one of the most dominant global international migration flows (UN 1997) and South and Southeast Asia is one of the dominant origin areas of such flows. The largest nation in the region, India, is estimated to have a diaspora of 15 million persons living overseas with US $150 billion in assets (Migration News, November 30, 1998). There are said to be 3.2 million overseas Pakistanis (Asian Migration News, June 15, 1999). Table 1 presents estimates of the numbers of South and Southeast Asian migrants in more developed countries. These are underestimates of the impact of immigration because the data are obviously incomplete; undocumented migrants are excluded and the children born overseas to migrants and later generations are not included. Nevertheless, the scale of the movement can be appreciated.

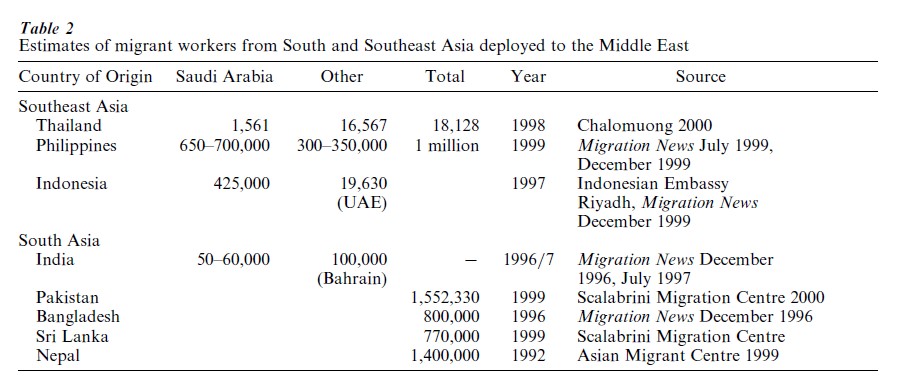

However, more-or-less permanent settlement in North countries is not the only type of movement out of South and Southeast Asia. International labor migration whereby workers from the region move to other countries to work, usually under contract, for a set period (usually around two years) before returning to their home country has expanded since the 1980s. One of the major streams of this type out of the region is directed toward the Middle East. There has been a long tradition of South Asians working in that region which extends back to colonial times, but the steep increase in oil prices after 1973 saw massive flows of foreign exchange into the region which fostered massive infrastructure construction which in turn saw the expansion of recruitment of foreign workers initially from South Asia but later from Southeast Asia.

In the late 1980s this movement changed to include more women and service workers. Again, data are poor since many Middle Eastern countries do not release information on migrant workers due to the sensitivity attached to heavy reliance on foreign labor in several countries where these workers in some cases out- number local workers. Nevertheless, Table 2 presents some information for the main labor-exporting countries. The bulk of migrant workers from Southeast Asia are unskilled while South Asia has sent both skilled and unskilled workers. Female domestic servants have become more significant in the movement over time, especially those from Indonesia, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka.

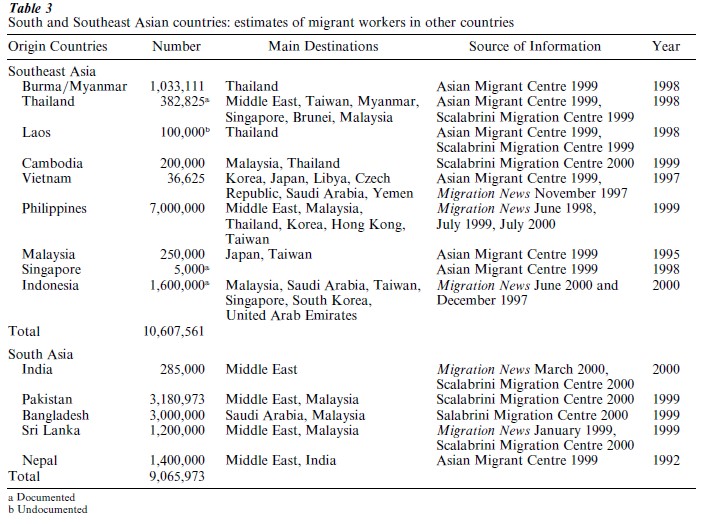

In the 1980s and 1990s there was a growing tempo of movement of international labor migrants to Asian destinations, including other countries in the Southeast Asian region. This is evident in Table 3, which consolidates estimates of the stocks of overseas migrant workers from the various nations of South and Southeast Asia. These indicate that for many the main destination is an Asian nation. In fact, several of the East and Southeast Asian nations which began their transitions to low fertility in the 1980s and 1970s have suffered significant labor shortages in recent years. This has been a function of both rapid economic expansion and the declining numbers of new entrants into their workforces due to low fertility. This has been accompanied by a distinct segmentation of their labor forces whereby local workers have eschewed entry into low-income, low-status jobs which have created niches for overseas migrant workers in these areas. Hence, particular industries in particular Asian countries have become quite dependent on foreign labor. These include some activities in countries like Thailand and Malaysia which themselves are supplying migrant workers to Japan and Taiwan. Hence, in Thailand the rice milling and fishing industries are heavily reliant on labor from Myanmar while in Malaysia the plantation and forestry industries rely upon gaining workers from Indonesia, the Philippines, and Bangladesh.

It is apparent, then, that one can recognize three distinct subsystems in South and Southeast Asian migration. One has involved movement to the so-called northern nations; another links the region to the Middle East; while a third involves intra-Asia movement. While permanent settlement in the case of the first subsystem and labor migration in the case of the second two are dominant, there are a number of other forms of international movement involved in the subsystems. Dealing first with the south–north movement, a most important factor was the abolition of racially biased immigrant selection policies in the main immigration countries (USA, Canada, Australia, etc.) in the 1960s and 1970s. Immigration policies were developed in which selection was based upon skill education and/or family linkages as well as acceptance of refugee/humanitarian migrants. Hitherto, migrants from South and Southeast Asia could not compete on an equal basis for migrant places with people from Europe. In addition, migration flowed along linkages established by colonial rule (e.g., Indians and Pakistanis to the UK, Indonesians to The Netherlands, etc.) or by military involvement (Koreans to the USA, etc.).

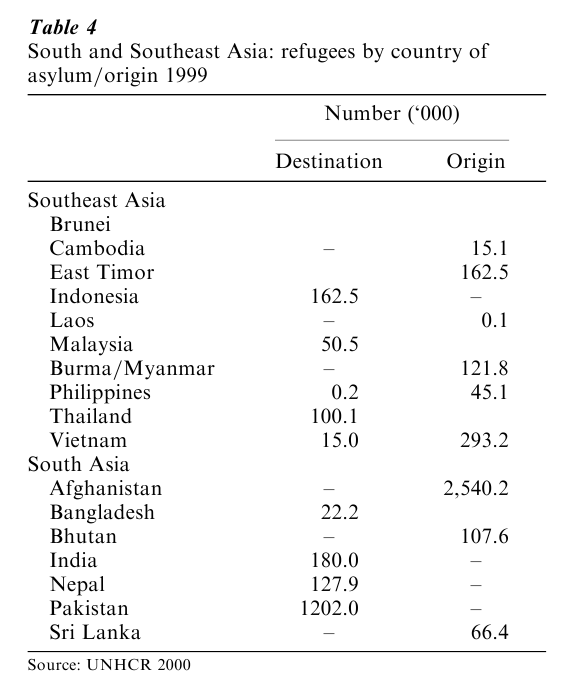

An important element in the south–north movement, as well as migration within Asia, has been that of the refugees. Table 4 shows the current stock of refugees in countries in the region. While there have been several such flows since the 1950s, two have been on a particularly large scale and have differed substantially in type. The outflow of refugees from Indochina following reunification of Vietnam in 1975 was predominantly initially to other Asian (especially Southeast Asian) nations.

This involved more than two million people, the vast majority of whom have been settled in third countries (predominantly in the ‘north’) or repatriated back to their home countries. These movements have resulted in substantial subsequent migration since these refugee settlers functioned as anchors in destinations to bring other family members to these destinations, often using the family reunification components of migration programs.

The second major refugee migration occurred from Afghanistan, especially into the neighboring nations of Pakistan and Iran. This involved several million people, most of whom were not settled in third countries or repatriated but stayed for long periods in their countries of temporary asylum. There have been many smaller but nevertheless significant movements, mostly involving movement into neighboring countries—Myanmar into Thailand, Tibet into India, Bangladesh into India, Philippines into Malaysia, etc.

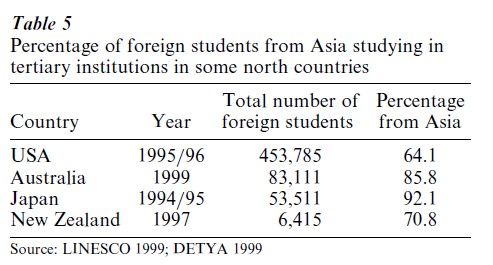

Another strand in the south–north migration has been the acceleration in the migration of students to undertake secondary but especially tertiary education. Table 5, for example, provides data on the percentage of foreign students from Asia studying in tertiary institutions in some north countries. In Australia, for example, over the 1983–1999 period the number of overseas students increased from 9,098 to 83,111. There is a strong connection between such movement and eventual settlement in the destination nation. Indeed, gaining an educational qualification in the ‘north’ country can facilitate entry as a permanent settler.

A related element in the intra-Asian subsystem involves the movement of trainees from labor surplus nations like Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines to countries with shortages such as Japan and Korea. The movement ostensibly is for workers of multinational companies in the former countries to spend a period in the home country of the companies to gain training. There has been discussion of the extent to which companies are using this system to import unskilled or semiskilled workers when government policy prevents such movement.

While the net effect of the south–north movement is emphatically in favor of the north, the flow in the opposite direction is not to be ignored. This in part involves former emigrants returning to their home country but in the case of some Southeast Asian nations also involves natives of north countries to meet the demands for skilled workers in areas like accountancy, engineering, management, etc. which cannot be met locally. Most of the latter will remain only temporarily in the Asian country. The fact that there is return migration into Asian countries from the north, however, is often neglected. It often can take the form of a ‘reverse brain drain’ involving highly qualified people who return and take up important positions in the economy or government of their home country.

Obtaining estimates of international migration in the South and Southeast Asian regions is very difficult. Data collection systems generally are not well developed and there is a high level of undocumented migration. The highly complex nature of the movement needs to be stressed as does the fact that there are complex linkages between the different types of movement.

3. The Migrants

Migration is always a selective process in that the groups of people who move differ from those who are left behind or those which they join at the destination. Each of the three main subsystems briefly described above is distinctive not just in terms of the countries involved but also the types of people who move. The south–north migration generally can be characterized as being selective of the better-educated and skilled populations since entry criteria in the destination countries usually require this, although ‘business’ migration programs involving the investment of minimum levels of personal wealth at the destination are increasingly common. Under family reunification and refugee humanitarian programs and the United States Quota Program, there are some, but limited, opportunities for unskilled people to move but the overall selectivity remains. One characteristic of the south– north movement is the increasing involvement of women such that in several north countries women immigrants from the region (especially Southeast Asia) outnumber their male counterparts.

The composition of the flows in the Asian and Middle East subsystems is quite different. While there are certainly exceptions (these include some of the flows out of South Asia and the Philippines), the outmovements are dominated by unskilled workers. These are directed at particular labor market niches at the destination which, due to low wages or low status, are unable to attract local workers. Several of these flows are selective of women so that in some sending countries (e.g., Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and the Philippines), women outnumber men among the outgoing migrant workers. These women especially are directed to a number of specific occupations which sometimes make them vulnerable to exploitation. These especially include work as domestics in private homes in destination countries but also in some cases are associated with the so-called entertainment industry. In some countries (e.g., the Philippines) it has been found that migrant workers sometimes take up jobs in the destination country which are at a level below their qualifications.

4. The Process

There can be no doubt that the level of international population movement in South and Southeast Asia has increased substantially since the 1980s. Whereas in the 1970s the possibility of international migration was only within the reach of relatively few people in the region, it is now within the calculus of choice of a much larger number of people and a wider range of socioeconomic, cultural, and gender groups. Clearly, the whole process of globalization, especially as it has impinged upon labor markets, has been an important factor. This has increased greatly the linkages between nations involving flows of goods, finance, ideas, etc., and it is inevitable that movements of people also have increased although the barriers erected by nationstates to flows of people have been reduced.

Neo-classical economics explanations have relevance for migration in the region. South and Southeast Asia contain four of the 10 largest labor surplus countries in the world. The demographic and economic gradients between richer and poorer countries both globally and within Asia have increased since the 1980s so that there are not only steep differences in income and wages between nations but also in the rate of increase of the working age populations. Laborimporting economies are undergoing economic transformation from manufacturing to service-based economies and this is creating jobs for migrant workers. Labor shortages in areas like information technology, management, and a number of skilled areas is encouraging the development of international labor markets but, also, the labor market segmentation referred to earlier is creating opportunities for migrant workers in low-skilled, low-paid, and low-status areas. The South and Southeast Asian region is able to supply workers both in the skilled areas (from South Asia, the Philippines) and the unskilled occupations.

Nevertheless the widening gaps between nations in population and economic growth and income and wage differentials are not sufficient explanation of the burgeoning of migration in the region, although they are an important component of any comprehensive accounting for it. There are a number of other elements which are also involved. Among the most important is the development of social networks between origin and destination nations. Empirical research indicates that the majority of movers from the region migrate to join family and friends who migrated earlier to the destination. A large proportion of South and Southeast Asians now have social capital in countries other than their own in the form of a family member or friend who lives and/or works in those countries. Those linkages form important conduits along which international migration, both documented and undocumented, takes place. The development of ever cheaper and better transport and communication systems enhances the operation of these networks in initiating migration.

Another element involves the so-called migration industry, which has a long history in the region but has proliferated in recent times. This involves a plethora of immigration agents, recruiters, travel agents, travel providers, immigration officials, labor brokers, and other intermediaries who are involved in initiating and facilitating international migration. Part of this infrastructure are the people smugglers and traffickers who transport migrants outside of government regulations but it also involves many who operate within the law. Another element is the greater involvement of government in international migration in the region. While governments in destination countries are predominantly concerned with controlling the numbers and characteristics of immigrants, those in sending countries increasingly are becoming involved in the emigration process. Realization that international migration can relieve under and unemployment at home and enhance foreign exchange earnings has seen governments in several nations intervene to encourage emigration and to protect the rights of their nationals living and/or working in other countries. Some countries have been active in encouraging former migrants with needed skills to return while others have policies and programs to encourage their nationals in other countries to invest their earnings in their home countries.

5. Issues

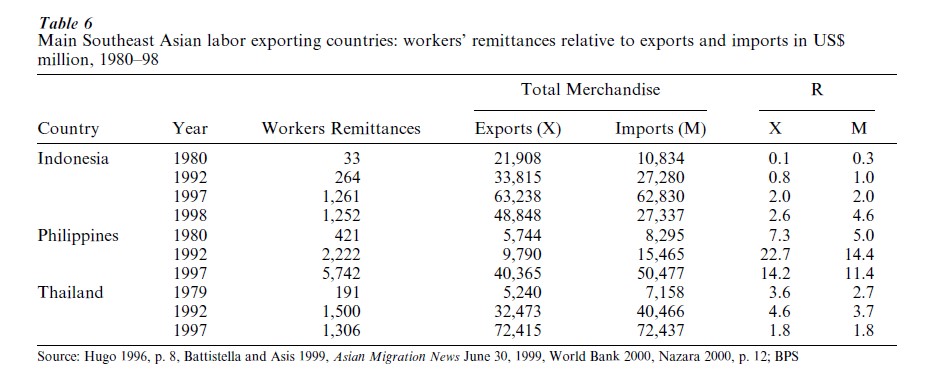

The proliferation of international migration in South and Southeast Asia has seen the emergence of a number of significant issues both in the countries of origin and destination as well as among the migrants themselves and their families. One of the most debated of these relates to remittances—those moneys earned by migrants abroad that are sent to or brought back to the country of origin. There is debate as to the scale and impact of these financial flows but the data relating to them are largely incomplete. This is because much of the flow does not pass through official channels. Nevertheless, it is clear that the impact of remittances can be considerable. Table 6, for example, shows the significance of reported remittances in relation to foreign exchange earnings from trade in three Southeast Asian countries. While global figures such as those in Table 6 understate the scale and impact of remittances nationally, there can be no doubt that their impact within regions of South and Southeast Asian countries is much greater. This is because migrants tend to be drawn from particular regions rather than randomly across the nation. Hence, remittances tend to be focused on particular parts of countries such as Kerala in India or Flores in Indonesia. Moreover, these regions are often among the poorest in the origin countries and the remittances represent one of the few sources of investment in those regions. For example, a December 1999 report from the State Planning Committee of Laos indicates that remittances from abroad represented 28 percent of all household earnings in the Vientiare Valley compared with 25 percent from agriculture, 22 percent from wages, and 18 percent from business (Litner 2000, p. 48). However, remittances have also been seen to increase costs and widen income distribution in origin areas as well. There have been several interventions by governments in the region to encourage nationals overseas to put their earnings in national banks and to invest in their home countries as well as to encourage the sending of remittances to the home country.

Another important issue relates to the exploitation of migrants from the region. While it is incorrect to depict all such migrants as victims subject to exploitation, there can be no doubt that some groups are vulnerable to exploitation of a number of kinds. This is particularly the case among some groups of female migrants, especially those who work in occupations where protection is difficult, such as domestic workers in private homes and in the entertainment industry. Those who are undocumented are especially vulnerable to exploitation but lack of knowledge and local languages and customs can also increase vulnerability of immigrants. Governments of sending countries vary considerably in the efforts they have made to protect their nationals abroad. The Philippines, for example, leads the way in this area but even so significant exploitation still occurs. The issues of protection of nationals overseas is most pressing but governments find it difficult to interfere in the affairs of other countries. Accordingly, some of the most effective protection comes from the activities of nongovernment organizations and through informal networks established by the migrants. Exploitation of the migrants can occur in the process of movement when they may be forced to pay exorbitant amounts of money or suffer physical abuse. There have been several documented cases of undocumented migrants from the region losing their lives due to suffocation or drowning in the process of migration. At destinations they can be subject to exploitation and discrimination especially if they are undocumented migrants. Such migrants usually are depicted as criminals rather than as victims of the groups that exploit them in the process of migration or at the destination.

The pressing issue of protection of migrants and migrant workers from the region is related to that of controlling the intermediaries in the migration process. While all such intermediaries do not operate outside of the law, a substantial number do. Indeed, the involvement of crime syndicates in people smuggling and trafficking has increased exponentially and has become an important issue in international crime. The multinational nature of these groups makes them difficult to control and their influence is widespread, even involving officials involved in immigration. The thriving of such organizations clearly is related to the failure of documented migration systems and enhanced policing of migration is unlikely to solve the problem of undocumented migration. Improvement of official migration systems must be part of the increasing international effort to combat the people smuggling and trafficking which is especially rife in South and Southeast Asia. In countries of origin there is a need for information programs which provide potential migrants with detailed, accurate information about the costs of the migration process and the nature of the experience at the destination. Studies in several countries indicate that migrants are often poorly informed on both these counts and this can lead to them paying excessive amounts to move and to them having false expectations of the destination. The latter, for example, results in up to one-half of Indonesian women going to the Middle East to work as domestics returning to Indonesia before their contract time has expired. There needs to be a crackdown on the activities of unscrupulous intermediaries in several countries.

The issue of south–north migration representing a ‘brain drain’ of skill and talent needed for development in the home countries is a longstanding one in the region. In several origin countries, however, the occupational profile of migrant workers is largely an unskilled and semi-skilled one so that movement out of a country like Indonesia certainly cannot be characterized as a brain drain. On the other hand, much of the movement out of countries like India, Pakistan, Philippines, and Singapore is of skilled and highly educated groups. In those cases, however, the movement is not necessarily a net economic loss to the nation. Economic studies have shown that in some cases individuals have a net positive economic impact if they go overseas and remit money back to their home country rather than remain behind. In countries like India and the Philippines there appears to be an oversupply of some skilled groups in relation to the opportunities available locally. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that the emigration of some skilled groups can be detrimental to local economies in some cases. With the globalization of labor markets such mobility is inevitable. Some countries in the region (e.g., Pakistan) have put in place programs to encourage former emigrants with certain skills to return to their home country. The growth of India’s information technology industry, for example, has lured some former emigrants to return.

The interrelationship between international migration and development in the region is much argued. There can be no doubt that international migration can have both positive and negative effects on the well-being of communities left behind. This presents a challenge to policy makers to put in place institutional structures which maximize these benefits and minimize the negative effects. All empirical evidence points to the fact that there is little to be gained from policies and programs designed to stop population movement when there are economic imperatives behind that movement. The challenge is in creating policies and structures which enhance the benefits of the movement.

There is a range of issues which relate to the experience of migrants from South and Southeast Asia in destination countries. Several groups settling in northern countries show a tendency to concentrate in particular communities or develop ethnic enclaves, especially in major metropolitan areas. Debate on this ranges between those who see such areas as barriers to the adjustment of migrants and those who see them as having a cushioning effect in allowing migrants to adjust to life in the new country in a gradual way and with the support of community networks. Other issues relate to discrimination experienced by some groups in housing and job markets as well as nonrecognition of qualifications leading to occupational skidding and deskilling.

6. Conclusion

The South and Southeast Asian region represents one of the world’s major reservoirs of potential international migrants accounting for more than one-quarter of the global population and several of its largest labor surplus economies. Until recently, the impact of international migration in the region has been limited but it is now of significance in all countries in the region. Although fertility decline has been significant the labor force in the region continues to grow rapidly. Economies in several countries in the region are also growing rapidly but all of the pressures which have created greater movement since the 1980s than previously will continue to operate. Hence, the twenty-first century will see an increase in the scale and complexity of movement out of, within, and into the region.

Bibliography:

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2000 Migration Australia 1998–99. Catalogue no. 3412.0, ABS, Canberra

- Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs 1999 Students 1999: Selected Higher Education Statistics. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra

- Garson J 2000 Recent trends in migration movements and policies in the OECD countries. Paper prepared for Workshop on Migration and the Labour Market in Asia, Tokyo, 26–28 January

- Leete R, Alam I (eds.) 1993 The Revolution in Asian Fertility: Dimensions, Causes, and Implications. Clarendon Press, Oxford; Oxford University Press, New York

- Litner B 2000 Far Eastern Economic Review

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 1998 Trends in International Migration: Continuous Reporting System on Migration: Annual Report. OECD, Paris

- Statistics Canada 1992 1991 Census of Canada. The Daily December 8

- United Nations 1997 World Population Monitoring, 1997: Issues of International Migration and Development: Selected Aspects. United Nations, New York

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) 1999 Statistical Yearbook 1999. UNESCO Publishing and Bernan Press, Paris and USA

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 2000 Refugees and Others of Concern to UNHCR: 1999 Statistical Overview. UNHCR, Geneva